Country risk: the best and worst places to mine

2021.05.23

Alongside management and location, country risk is one of the most important factors to consider in deciding whether to invest in a mining property.

Resource nationalism is the tendency of people and governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over natural resources located on their territory. It has been identified as one of the key risks for investors in the natural resources sector.

Miners are easy targets because mining is a long-term investment and one that is especially capital intensive. Mines are also immobile, so mining companies are at the mercy of the countries in which they operate. Outright seizure of assets happens using the twin excuses of historical injustice and environmental or contractual misdeeds. There is no compensation offered and no recourse.

Governments may get in the way of miners’ progress by implementing anti-mining agendas and/or thinking up new ways to hit the extractive industry with higher taxes.

Some have gone beyond taxation in getting more out of the mining sector with a wave of requirements such as mandated beneficiation (where ore is processed locally rather than exported raw), export restrictions (eg. Indonesia) and increased state ownership of mines (eg. Mongolia).

Part and parcel to resource nationalism is “country risk”.

This is one of the most serious and unpredictable risks facing mining operations and investor interests — where the political and economic stability of the host country is questionable and abrupt changes in the business environment could adversely affect profits or the value of the company’s assets.

We’ve seen many instances of companies losing assets that were lawfully theirs. Several countries come to mind as places where shareholders could, without warning, receive news that operations have been taken over by the government or its friends, or where permits get delayed or canceled outright.

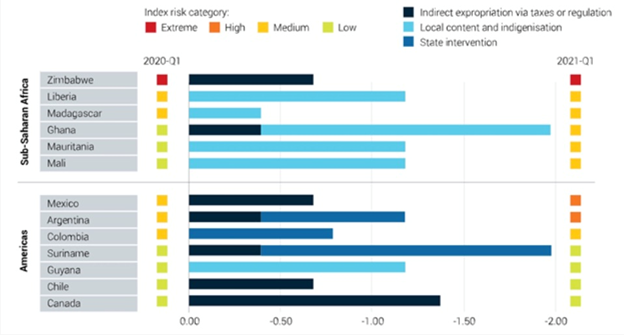

A recent study pointed to 34 countries that have seen a significant increase in resource nationalism risk over the past year. Countries now rated “extreme risk”, according to the March 2021 report by Verisk Maplecroft, include major African copper producers Zambia and the DRC.

According to the risk consultancy, resource nationalism is increasing in the wake of the covid-19 pandemic. Countries most at risk are those dependent on the minerals or hydrocarbons they export, and mining jurisdictions that have suffered significant economic contraction as a result of the coronavirus. These places are more likely to try and recoup their financial losses by targeting the mining industry in their countries.

In its report, Maplecroft says there is an increasing trend of “state interventionism, creeping expropriation, and indigenisation” — interventionist measures that are more subtle than, say, outright nationalization or large tax increases imposed on foreign mining or energy companies.

In Latin America, the firm points to two influences behind resource nationalism. The first is ideologically driven, such as Argentina’s nationalization of Repsol’s interest in YPF; and the second is increased pressure from communities to exert greater control over their mineral resources. The latter is best personified by Chile. Triggered by the worst social unrest in a generation, anchored in rampant inequality, the country reportedly has just elected an assembly that will place responsibility for writing a new constitution in the hands of the left wing.

The reforms could give more power to indigenous communities and expand water rights, including a potential ban on mining in areas where there are glaciers, along with increased state ownership of water desalinated by mining companies.

Zambia made it into Maplecroft’s top riskiest places to mine in due to an attempted liquidation of Konkola Copper Mines, whereas in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Congolese government in 2018 raised taxes on mining firms and increased royalties. The country is Africa’s biggest producer of copper and cobalt.

One explanation of why resource nationalism has picked up in recent years has to do with globalization. During the 1970s and ‘80s it was common to see developing world governments nationalizing industries. However when globalization emerged in the 1990s, there was a need for foreign investment as governments privatized industries, resulting in fewer attempts to seize foreign-owned assets like mines and factories.

This changed when governments in Latin America, primarily, saw mining profits moving out of the country and they sought to seize greater control over their mineral wealth.

According to a report by Clifford Chance, a law firm, drivers of resurgent resource nationalism in the 21st century include:

- Over-dependence on natural resources.

- Fast growing populations whose social, educational and health needs are not being satisfied.

- Evolving politics. A government that comes to power on a nationalist platform or that is more critical of foreign investment may be more likely to change the terms of foreign investment.

- The need for jobs.

- The lack of infrastructure and social services.

- Outdated or inappropriate laws.

- A lack of transparency in the licence and concession award process.

- Exploitative contracts. Some foreign investors have taken advantage of political instability, corruption or a kleptocratic state to negotiate terms that are often opposed by the population or a new government.

- High commodity prices and competition for a depleting supply of natural resources.

These factors can create pressure on a State to increase its “take” from its natural resources.

By no means a new phenomenon, some of the ways that countries nationalize resources are through direct expropriation; increasing taxes or royalties foreign miners pay; terminating or suspending licenses/ permits they need to operate; and imposing new and often expensive regulations.

Security of supply

Resource nationalism is closely tied to security of supply.

According to a 2019 UN report, over the last five decades, mineral extraction has tripled — and accelerated since 2000 as new economies (ie. China and India) require huge amounts of materials for building new infrastructure.

Without a way to replace all the resources we consume — food, fertilizers, energy, metals, etc. — we are gradually depleting nature’s bounty, at a rate that is unsustainable, long-term.

Humans are currently withdrawing more natural resources then our Earth “bank” is able to provide. How much more? At today’s rate of withdrawal we need just over another half-Earth. We’re on track to require the resources of two planets by 2050.

If today, everyone on Earth were to start consuming the same amount of natural resources as the average Australian, we’d need 5.4 planets, an ecological overshoot of 4.4 planets.

If we keep going, and economies keep growing, we’re eventually going to run out. The problem is made worse by the global population increasing, along with the continuing wants of people in the developed world (“the West”) and in less-developed countries (who are demanding houses, cars, fridges, cell phones, etc.), putting more pressure on our finite resources.

A good example is oil. In the space of just 10 years, from 2008 to 2018, it has been reported that humans burned through about one-third of all the oil ever consumed.

As competition for scarce resources becomes more intense, access to a secure and sustainable supply of raw materials will become the number one priority for all countries. Increasingly we are going to see countries ensuring their own industries have first rights to locally produced commodities.

Another way to think about it, is that resource nationalism wouldn’t exist in a world where resources are plentiful, or where there are substitutes for resources that run out.

“Resource nationalism is a counterpoint to the cornucopian dreams of the world’s resource optimists,” states a 2020 column in resilience.org.

Examples

Resource nationalism is fairly common in the mining and oil and gas industries. The amount of money, both profits and tax revenue, at stake, makes extractors good targets of governments needing a temporary or permanent infusion of cash.

Let’s start with the most obvious manifestation of resource nationalism: expropriation. In 2011 the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez nationalized the gold industry, and in 2006 then-president Evo Morales of Bolivia signed a decree stating that all natural gas reserves were to be nationalized. In 2012 Argentina grabbed a majority stake in the nation’s biggest oil company, YPF, from Spain’s Repsol, six months after President Cristina Fernandez won a landslide election. Mexico nationalized its oil industry back in 1938.

The state need not take the whole property for it to amount to expropriation. A government may instead require that the foreign investor divest a portion of its ownership interest by selling a certain percentage to the state.

In 2012 Indonesia announced that foreign ownership of some mines would be capped at 49% and gave companies who exceeded this threshold 10 years to sell their excess ownership percentage. A year earlier the government of Mongolia tried to negotiate its 2009 investment with Ivanhoe Mines which held a 66% share of the Oyu Tolgoi copper-gold complex, by moving forward the date it could exercise its option to increase its 34% share to 50%.

Another way to limit foreign companies’ profits and maintain local control over mineral processing is to impose a ban on the export of raw ores. In 2012 Indonesia applied a 20% tax on exports of unprocessed metals including nickel and gold; a ban on nickel ore exports was re-imposed in 2019 to develop the country’s domestic nickel refining industry.

A more subtle way developing countries have turned the screws on international mining companies is to change their mining codes to include terms more favorable to the host government.

During the 2000s, Angola, Botswana, Brazil, and the Republic of Guinea were among the countries to adopt this tactic.

Export revenues may also be repatriated.

Experienced resource investors will recall how Argentina in 2011 ordered the repatriation of energy and mining companies’ export revenues in order to slow capital flight estimated at around $3 billion per month.

Affirmative action is a way of ensuring that foreign-headquartered mining companies employ local workers.

In South Africa, new legislation was passed in 2004 requiring that 15% of mining companies’ equity be owned by Historically Disadvantaged South Africans (HDSAs) within five years. After 2009, the percentage increased to 25%.

Zimbabwe’s indigenization policy requires that foreign-owned companies transfer at least 51% of local operations to black investors.

Most people when they hear the term resource nationalism associate it with developing countries. Yet there have been numerous examples in the West too, typically manifested as changes to tax regimes or restrictions on foreign investments. For example:

- Australia’s 2012 Minerals Resources Rent Tax (MRRT) imposed a 30% tax on iron ore and coal profits, over a certain amount.

- The UK government in 2011 proposed a windfall tax on North Sea oil profits that was ultimately rejected by the offshore oil industry and replaced by tax breaks.

- In 2010 the Canadian government rejected BHP Billiton’s offer to purchase Potash Corporation, deeming the take-over to be against Canada’s national interest.

Nor does resource nationalism always have to involve minerals or hydrocarbons. The phenomenon can be found in a variety of sectors including agriculture and fisheries.

In the late 1980s and early ‘90s, there was a shift toward resource nationalism in the Pacific tuna fishing industry. Despite the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea establishing the 200-mile limit, conflicts broke out between Pacific Island nations and countries with large fishing fleets like Japan. When the United States refused to recognize Pacific states’ claims to tuna in the exclusive economic zones, the island nations began to adopt policies that encouraged more local control over their fishing industries.

A dust-up between the Malaysian and Indian governments regarding India’s invasion of Kashmir led to a ban on palm oil imports from Indonesia, which along with Malaysia produces 90% of the world’s palm oil.

Lessening risk

Mining being so highly capital intensive — constructing a new mine is usually measured in the hundreds of millions of dollars — it is incumbent upon governments to have policies that create confidence that taxes and regulations will not be capriciously changed.

That, however, is something neither investors nor mining/ exploration companies have any control over. So how to protect your, or your company’s investment against resource nationalism? The literature on this topic offers a number of suggestions.

The above-mentioned Clifford Chance report notes the greatest threat to foreign investors is when changes are made after significant investments have been made, often despite earlier promises of fiscal stability.

It warns that resource nationalism may make foreign investors less willing to invest in the country; cause investors to reduce their exposure; and make projects more difficult and expensive to finance.

The report recommends that foreign investors structure (and document) their deals to minimize the risks of resource nationalism, using mechanisms such as contractual remedies and bilateral investment treaties; and take on political risk insurance.

A recent article, by legal website Lexology, names 10 key issues that mining companies and their investors should consider when it comes to resource nationalism:

- Investment structuring, whereby thought is given to the ability to gain access to international law or arbitration

- State participation, whereby the foreign investor offers the state some form of participation from the outset

- Making use of tax treaties, or double tax agreements, to manage the risk of tax on profits and capital gains

- Consider incorporating environmental and human-rights standards, which usually falls under ESG

- Have access to sufficient legal remedies, in the event of sanctions or trade bans

- Look into whether the company can negotiate with a state regarding its local content rules, and if not, whether the investment can be structured through arbitration

- Carry our rigorous due diligence prior to investing, to avoid or at least be able to document bribery and corruption

- Retain experienced local counsel

- Adhere to mining-relevant governance frameworks such as the Responsible Gold Mining Principles, that could be relevant in an investor-state dispute

- Prioritize employment/ labor issues and implement the right culture and legal framework

Fraser Institute rankings

Of course the far easier way to lessen, and indeed eliminate, the risk of resource nationalism, is to steer clear of countries that are ranked highly for investment risk.

For many years the mining industry has been guided by the Fraser Institute’s annual investment attractiveness index, which measures the the attractiveness of a jurisdiction based on factors such as onerous regulations, taxation levels, the quality of infrastructure, and other policy-related questions that survey respondents answered.

According to the Fraser Institute’s 2020 Annual Survey of Mining Companies, Nevada was the highest-ranked for investment attractiveness, followed by Arizona and Saskatchewan.

At AOTH resource nationalism/ country risk is always top of mind when I do my due diligence on a company I’m considering featuring on aheadoftheherd.com.

In fact it is no coincidence that all of the resource companies I’ve currently brought on as clients appear on the less-risky left side of the rankings seen tabulated below. Only one client, Magna Gold, has a project in Mexico, which appears high up in the top right column, narrowly missing the left column by three positions.

Top ranked Nevada hosts two AOTH companies:Getchell Gold and Victory Resources.

Getchell Gold (CSE:GTCH, OTC:GGLDF) has four projects in top-ranked Nevada. With over $3 million in its treasury, Getchell is cashed up and ready to continue exploring two of its Nevada properties, Fondaway Canyon and Star. Drilling is scheduled to start next week. Read more

In early April, Victory Resources (CSE:VR, FWB: VR61, OTC:VRCFF) began a diamond drill program on its Loner property in Nevada. The program calls for 7-10 short diamond drill holes in the vicinity of the historical workings that exploited the Loner vein system. In addition, Victory recently staked the Black Diablo project in Nevada to complement the company’s interests in the Loner property, which is in close proximity. Read more

Fifth-ranked Alaska hosts two AOTH companies: Freegold Ventures and Graphite One.

At Freegold Ventures’ (TSX:FVL) flagship Golden Summit property, a drill program that started in February 2020 was designed to test a revised interpretation based on Freegold’s work that higher-grade mineralization may extend to the west of the old Cleary Hill Mine workings. Backstopped by a global historic resource of 6.524 million ounces of gold and $30 million in cash, my money is on Freegold’s Golden Summit project cruising to +10 million ounces. Read more

Located on the Seward Peninsula in western Alaska, Graphite One’s (TSX.V:GPH, OTCQB:GPHOF) Graphite Creek property hosts America’s highest-grade large flake deposit. Looking to advance what would be an integral part of the US graphite supply chain, Graphite One in February announced the completion of two private placements, raising C$10 million. Proceeds will be used to further develop Graphite Creek, including a prefeasibility study projected for completion by the end of Q2 2021. Read more

Manning Ventures (CSE:MANN, FSE: 1H5) has assembled two iron ore projects in 6th ranked Quebec with past exploration history, carrying high development upside. Poised to capitalize on high iron ore prices, Manning is currently planning preliminary exploration programs at both Lac Simone and Hope Lake. Read more

Also in Quebec, Renforth Resources (CSE:RFR, OTCQB: RFHRF, FSE: 9RR) continues to deliver good news for shareholders, in April announcing new assay results for the 2020 drill program on its Parbec open-pit constrained gold deposit. Parbec, which sits on 1.8 km of the Cadillac Break, neighbors Canadian Malartic, Canada’s largest gold mine. The company also recently commenced a 3,500m drill program at Surimeau, which hosts gold, nickel, copper, zinc and other metals in various settings at several locations on the large property. Read more

Staying with “la belle province”, Lomiko Metals’ (TSXV:LMR, OTC:LMRMF, FSE:DH8C) flagship project is the La Loutre flake graphite property, located 53 km east of Imerys Carbon and Graphite’s Lac des Iles mine. Lomiko is currently working on a preliminary economic assessment (PEA) at La Loutre, and in 2019 completed a drill campaign at the EV Zone. The company recently optioned the Bourier lithium property in the James Bay region of Quebec. According to Lomiko, Bourier is “potentially a new lithium field in an established lithium district.” Read more

Eighth-ranked Newfoundland & Labrador, on Canada’s East Coast, is the site of a modern-day gold rush in Central Newfoundland. Exploits Discovery Corp (CSE:NFLD, FSE:634-FF) is moving right along with its 2021 exploration program involving up to 13,500m of drilling at five targets — all of which are very prospective. Three of five host visible gold at surface with impressive grades up to 194 g/t Au. Exploits hasn’t even started drilling yet and it’s already more than doubled in less than a month — another AOTH winner for those who bought shares. Read more

Finland, ranked 10th on the investment attractiveness index, hosts AOTH’s Palladium One Mining.

Palladium One’s (TSXV:PDM, FSE:7N11, OTC:NKORF) LK PGE-nickel-copper project is part of an intrusive belt that runs east-west across Finland and into neighboring Russia. Palladium One recently secured a $12.5 million cash injection from Sprott Capital Partners. The bought deal financing (upsized to C$15M due to being over-subscribed) ensures a healthy treasury that PDM can draw from, as it continues to explore its projects in Ontario and Finland. 27,000 meters is planned this year from a total exploration budget of $11.5 million. Read more

ZincX Resources and Dolly Varden Silver both have projects they are developing in British Columbia, ranked 17th by the Fraser Institute.

ZincX’s (TSX.V:ZNX, Frankfurt:M9R, US:ZNCXF) Akie property in northeastern BC is within the geological district known as the Kechika Trough, which is highly prospective for zinc, lead and silver. To date, drilling totaling 64,000 meters has defined a significant body of mineralization capable of matching, if not surpassing, the production of some of the largest zinc deposits found in the US. Read more

Dolly Varden’s (TSX.V:DV, OTC:DOLLF) silver properties in the ‘Golden Triangle’ of northwestern BC, consist of two past-producing silver deposits. Dolly Varden and Torbrit became part of British Columbia’s mining lore, featuring assays as high as 2,200 ounces (over 72 kg) silver per ton, with historical production of 20 million ounces Ag, between 1919 and 1959. Dolly Varden’s goal is to try and extend the Torbrit deposit through step-out drilling. The company finds itself in the rare position of being a pure-play silver explorer, in a space where most silver production comes from lead-zinc deposits or is a by-product of gold mining.Read more

Two spots below British Columbia, Ontario hosts three AOTH companies, Marvel Discovery Corp, Falcon Gold and Palladium One Mining.

Marvel Discovery Corp. (TSX.V:MARV) has two very interesting properties in northwestern Ontario, where a number of juniors have acquired ground and are working properties in close proximity to Agnico Eagle’s monster Hammond Reef gold deposit. Indeed “close-ology” appears to weigh heavily in its favor, with Grid Metals and Canadian Palladium reporting recent success at the drill bit near Pecors, and Falcon Gold delivering sweet assays from its Central Canada gold & polymetallic project, located just east of Blackfly. Read more

Falcon Gold (TSXV:FG, FSE:3FA.G, OTC:FGLDF) continues to make excellent progress at its flagship Central Canada gold project, located 21 km east of Atitokan, and 160 km west of Thunder Bay, Ontario. Falcon outlined its 2021 exploration plans in a March 2 news release, first explaining that the Central Canada property hosts two types of targets — the high-grade gold zones the 2020 drill campaign focused on, and copper-cobalt sulfides associated with massive iron sulfides and oxides hosted in the Quetico fault. The company anticipates collaring up to 20 drill holes targeting the gold mineralization in the Central Canada gold mine shaft area; and testing other gold zones such as the mineralized quartz-feldspar porphyries and the Northern (No. 2) vein. Read more

Palladium One’s (TSXV:PDM, FSE:7N11, OTC:NKORF) Tyko nickel-copper-PGE property near Marathon, Ontario, contains twice as much nickel as copper, and equal amounts of platinum and palladium. On Jan. 5 PDM announced assay results from the first two holes of a maiden drill program at the Smoke Lake target, completed last year. A second-phase, 2,000m drill program started in April. According to Palladium One, the most significant result of this Phase 2 drill program, was the linking of massive sulfide mineralization in the “upper conductor” with the “lower conductor”. Read more

In the bottom third of the left column of the Fraser Institute rankings, we find three more locations for AOTH companies: Colombia, Peru and Sweden. We are surprised to see Chile ranked higher than Peru and Sweden, given all of the above-mentioned resource nationalism nonsense, but note that these rankings are for 2020 and published in February 2021. If things continue, we expect Chile to fall significantly down the list when the 2021 rankings come out next year.

Colombia-focused Max Resource Corp’s (TSX.V:MXR, FSE:M1D2, OTC:MXROF) CESAR project is situated along the world-famous Andean Copper Belt, where silver is also abundant. It lies on a massive sedimentary system covering a cumulative 220-km strike of highly prospective Cu-Ag mineralization. Max is the first company to explore all of the copper and silver-rich areas covered by the CESAR property. The junior already has multiple non-disclosure agreements in place to advance the project, including a collaboration agreement with an industry-leading copper producer. Read more

Exploring in Peru, we find Tinka Resources (TSXV:TK, OTCP:TKRFF) and its flagship Ayawilca project. While the company’s exploration focus has been on areas of zinc mineralization, in 2015 the company made a new tin discovery at what is now called the Ayawilca Tin Zone. Mineral resources at this zone are estimated at 201 million pounds of tin, plus 67 million lb of copper and 8 million oz of silver, all in the inferred category occurring as cassiterite. The potential value of Tinka’s flagship project got even bigger this month with the announcement of new assays from the 7,600-metre, 21-hole drill program completed during 2020-2021.Read more

Norden Crown Metals (TSXV:NOCR, OTC:NOCRF, FSE:03E) is searching for high-grade silver and zinc deposits in Scandinavia. The Canadian firm recently started drilling at Fredriksson Gruva, a past-producing mine in Sweden originally discovered in 1976. Having completed the first three drill holes, the company has successfully shown not only that the mineralization continues at depth, but that it has qualities consistent with a Broken Hill Type (BHT) deposit. BHT silver-zinc-lead deposits constitute some of the largest and highest-grade ore deposits in the world. Read more

Magna Gold (TSXV:MGR, OTCQB: MGLQF) earlier this month put the final touches on its plan to acquire the San Francisco gold mine in Mexico. Looking to re-establish San Francisco as a profitable mine, in spring 2020 Magna agreed to buy the Sonora-based project for nearly 20% of the company’s share capital, plus a cash payment 12 months later. The 47,395-hectare property consists of two previously mined open pits (San Francisco and Chicharra) and associated heap leaching facilities close to the San Francisco pit. Since the acquisition, Magna has completed an updated pre-feasibility study (PFS) on the property, showing nearly 100 million tonnes of mineral resources (measured and indicated) with an average gold grade of 0.446 grams per tonne (g/t). Read more

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Richard owns shares of:Getchell Gold (CSE:GTCH, OTC:GGLDF), Freegold Ventures (TSX:FVL), Graphite One (TSX.V:GPH, OTCQB:GPHOF), Max Resource Corp. (TSX.V:MXR, FSE:M1D2, OTC:MXROF), Norden Crown Metals (TSXV:NOCR, OTC:NOCRF, FSE:03E)

The following companies are advertisers on Richard’s site aheadoftheherd.com:

Getchell Gold (CSE:GTCH, OTC:GGLDF), Graphite One (TSX.V:GPH, OTCQB:GPHOF), Max Resource Corp. (TSX.V:MXR, FSE:M1D2, OTC:MXROF), Norden Crown Metals (TSXV:NOCR, OTC:NOCRF, FSE:03E), Victory Resources (CSE:VR, FWB: VR61, OTC:VRCFF), Manning Ventures (CSE:MANN, FSE: 1H5), Renforth Resources (CSE:RFR, OTCQB: RFHRF, FSE: 9RR), Lomiko Metals (TSXV:LMR, OTC:LMRMF, FSE:DH8C), Exploits Discovery Corp (CSE:NFLD, FSE:634-FF), Palladium One (TSXV:PDM, FSE:7N11, OTC:NKORF), ZincX (TSX.V:ZNX, Frankfurt:M9R, US:ZNCXF), Marvel Discovery Corp. (TSX.V:MARV), Dolly Varden (TSX.V:DV, OTC:DOLLF), Falcon Gold (TSXV:FG, FSE:3FA.G, OTC:FGLDF), Tinka Resources (TSXV:TK, OTCP:TKRFF), Magna Gold (TSXV:MGR, OTCQB: MGLQF)

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.