The heat is on

2022.07.14

In Winnipeg, the hottest day of the year, on average, is nearly 40 degrees Celsius, while in Whitehorse, the mercury blasts past 31.4. A moderating coastal climate means little to Victoria, which averages 33.1 degrees, and Toronto, the most humid city in Canada, becomes even less bearable, with the temperature climbing to a sweltering 38.4.

These are the average hottest temperatures of the year in the new Canada, based on a higher-carbon atmosphere, one of three scenarios put together a few years ago by The Prairie Climate Centre and graphed by The Globe and Mail.

If climate change doesn’t stop, Toronto will see over 100 days of searing-hot weather, according to the University of Winnipeg’s Prairie Climate Institute, which assembled the projected temperatures for Canadian cities as part of an interactive website that allows Canadians to see the likely impact of global warming on where they live.

The warming of the planet could occur at a much faster rate when “feedback loops” are slotted into climate equations. This is what happens when one change causes another change to occur, worsening the first change. NASA states that climate feedbacks could double the amount of warming caused by carbon dioxide alone. A well-known feedback loop is the disappearance of polar sea ice. This exposes dark ocean to sunlight, warming the oceans. When ice covers the poles, the sunlight is reflected back to the atmosphere, keeping the oceans cool. As the planet keeps warming, more ice disappears, exposing more water, further raising ocean temperatures, and sea levels.

Heat, that is getting worse every year and in some parts of the world is becoming literally unbearable (more on that below), is inextricably linked to droughts and fresh water loss. Here’s how it works: a lack of precipitation in the mountains from a new or prolonged drought leads to a low snow pack, lessening the annual freshet that fills up rivers, that convey fresh water into lakes and reservoirs. If this cycle continues year after year, hydro-electric power generation is imperilled, because the reservoirs are too low (such as Lake Mead, discussed below), as well as nuclear power generation that depends on vast amounts of water to run water-cooled nuclear reactors. This leads to blackouts, when residents and businesses who are running their air-conditioning full tilt to get some relief from the scorching heat, find the grid is overwhelmed. In future, there simply won’t be enough water to supply the amount of electricity required.

As the outside conditions become hotter, yet the power to cool becomes restricted, and more expensive, residents are forced to move to cooler areas. Mass migrations pit migrants against existing inhabitants, for increasingly scarce resources, including water, food, housing, jobs, etc., setting the stage for conflict on a global scale.

Sound far-fetched? It won’t be, once you get to the end of this article.

Let’s begin with the importance of fresh water and how we’re losing it.

Water’s importance

The problem of severe water stress in the United States — and elsewhere — is serious and getting worse. Water stress is what happens when the demand for water exceeds the amount available, or when poor quality restricts its use. It most commonly occurs in areas where available water supplies have been over-exploited, often due to agriculture or urban development.

Most people are unaware that the amount of fresh water globally is extremely limited. Ninety-eight percent of the world’s water is in the oceans — which makes it unfit for drinking or irrigation. Just 2% of the world’s water is fresh, but the vast majority of our fresh water, 1.6%, is in a frozen state, locked up in the polar ice caps and glaciers. Our available fresh water (.396% of total supply) is found underground in aquifers and wells (0.36%) and the rest of our readily available fresh water, 0.036%, is in lakes and rivers.

The remarkably small global resource of fresh water is in serious peril due to climate change, increased demand and polluted water supplies.

National Geographic reminds us that, due to the water cycle, all the water around today was here in one form or another hundreds of millions of years ago. We’ve always had a relatively constant water supply throughout history, whether it’s in fresh water, salt water, glaciers, continental ice sheets (Greenland, the Arctic), or polar sea ice.

The trouble with this fact is it leads to complacency about the availability of fresh water. We think we’ll always have enough, especially in the developed world where fresh water is only ever a tap turn away. We don’t realize that water is a finite resource that the planet is in serious danger of running out of.

“Whisky is for drinking; water is for fighting over.”

– Mark Twain

According to the UN, demand for water is expected to grow 55% by 2050, with most of the need (70%) driven by irrigation, to feed the expanding global population, expected to hit 10 billion by 2050. Water for energy use is forecast to rise by 20%.

One estimate, quoted by Scientific American, finds that electric power generation consumes more than 3 trillion gallons of water globally per year. The reason power plants are so thirsty is that steam has to be cooled, condensed back into water and recycled through the system. Most of the water is consumed through the cooling process.

The supply won’t be enough to satisfy everyone. By 2025, 1.8 billion people will live in areas where water is scarce, and two-thirds will be residents in water-stressed regions, reports National Geographic.

We are dancing much closer to the knife edge of water scarcity than we like to think.

Water under attack

Glacial melt

Most of the world’s fresh water is contained within glaciers or hard-packed snow that falls in the mountains and becomes freshet in the spring, filling creeks, rivers, lakes, rechargeable aquifers and reservoirs. Mountain glaciers sustain large numbers of people, who collect the annual freshet that flows from higher elevations and is funneled into creeks.

We know from several years of measurements, that mountain glaciers are in retreat.

Over the last few decades, almost all the world’s glaciers have shrunk and the rate of decline is accelerating. An expert on glacier dynamics, associate professor Jeff Kavanaugh at the University of Alberta, expects that between 60 and 80% of the ice volume in BC and Alberta will be lost by 2100.

Of course, the main factor driving glacial melt is rising temperatures. A rise of 1.5 C is considered to be the tipping point, beyond which further warming is expected to have disastrous economic, political and environmental consequences. We are already at 1.1C; arguably there is no stopping it. The Earth will warm until it starts cooling. The proof is in the geologic record. All we can do is try to manage the effects as best we can.

As for how melting glaciers affect our water supply, Prof. Kavanaugh says glaciers keep our rivers flowing when other water sources, like snow melt, dry up. He predicts the next few decades will be marked by high flows in our glacial rivers, but after that, “it will start to fall off a cliff. How much water is flowing through the river as a function of that time of year is going to start changing remarkably.”

Personally I see the latter as “nature’s cover-up”. People can easily be fooled into thinking that streams and rivers are full because there is plenty of snowpack, when in fact it’s because glaciers are melting. The cover-up may last several years, it takes a long time for glaciers to completely melt, but once they do, all that will be left to re-charge rivers, lakes and reservoirs, is the annual snowpack, that will become smaller and smaller as the Earth warms. Glacial melt is happening on a global scale, clarifying the enormity of the problem.

Aquifer depletion

Fresh water aquifers are one of the most important natural resources in the world, but in recent decades the rate at which we’re pumping them dry has more than doubled. These fast-shrinking underground reservoirs are essential to life on the planet. They sustain streams, wetlands, and ecosystems, and they resist land subsidence and saltwater intrusion into our freshwater supplies. Some of the largest cities in the developing world – Jakarta, Dhaka, Lima and Mexico City – depend on aquifers for almost all their water. Most rural areas pump groundwater from wells drilled into an aquifer.

According to the BBC, of the world’s major aquifers, 21 out of 37 are receding.

Saltwater intrusion

If too much groundwater is pumped out from coastal aquifers, saltwater may flow into them, causing contamination of the aquifer. Many coastal aquifers – the Biscayne Aquifer near Miami and the New Jersey Coastal Plain aquifer for example – have problems with saltwater intrusion.

Saltwater intrusion is also caused by rising sea levels caused by melting ice. The warming of the Earth’s surface has caused a widespread retreat of the glaciers at both poles.

All of this melting ice has caused sea levels to rise, from between seven and eight inches, NASA states, with the most rise occurring since 1993. The expansion of ocean water as it warms also causes higher sea levels.

Pollution

Water quality has always been of utmost importance to the health of human populations. However, despite the advances of science, many fresh water supplies are getting fouled. Since the 1990s, pollution has worsened in almost every river in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The situation is expected to deteriorate due to runoffs of fertilizer and other agrochemicals that lead to the growth of pathogens and algae blooms. About 80% of industrial and municipal wastewater is discharged without treatment.

Extreme heat

The climate on planet Earth is changing, and a lot faster than many had anticipated.

On June 29, 2021, Canada’s highest-ever recorded temperature, 49.6 C, was reached in Lytton, BC. The day after, the village of 250 inhabitants was destroyed by fire — buildings razed to their foundations and the hulking wrecks of cars left smoldering.

The “heat dome” that covered much of western North America at the end of last June, shattered temperature records, including Portland Oregon’s 46.6 C (116F) scorcher. It killed 619 people in British Columbia alone. An attribution study quoted by Climate Brief said the extreme heat would have been almost impossible without climate change.

United States

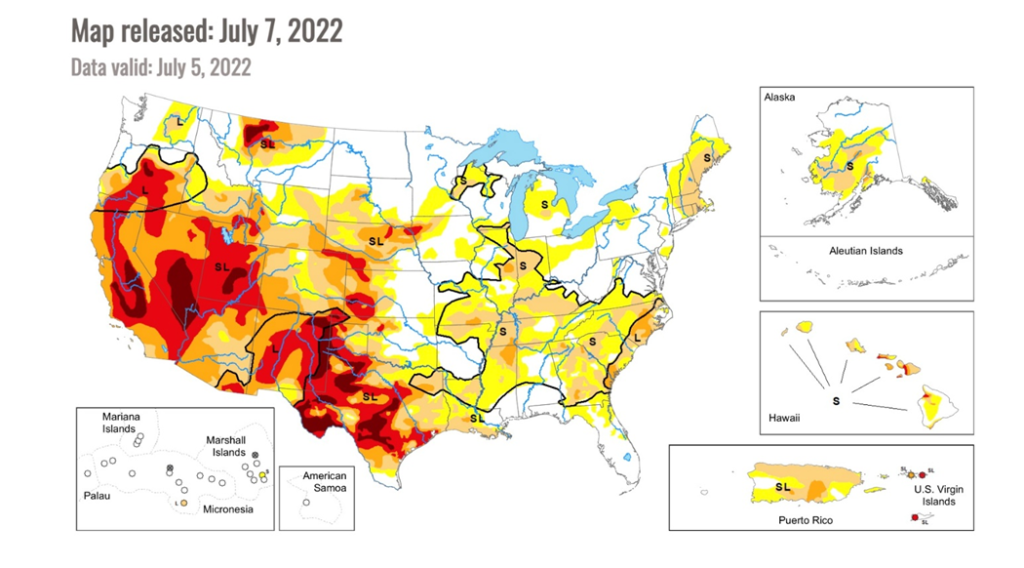

While inhabitants of the Canadian Western provinces and the US Pacific Northwest have been spared a repeat of last summer, those living in the southwest and central United States have not been so lucky.

A heat dome that has been sitting over the region saw at least 10 temperature records broken over the weekend.

USA Today reports the Denver airport in Colorado hit 100 degrees on Saturday, July 9, surpassing the 98 degrees set on the same day last year; Colorado Springs reached 97 degrees, and in Camp Mabry military base in Austin, Texas, the mercury climbed to 106 degrees, breaking the previous record of 105, set in 1925 and 2009. It was even hotter in Waco, Texas, which reached 108 degrees Saturday, far exceeding the 104 set in 1917, 1935 and 1978.

Heat advisories stretched from Central Texas east to Georgia, South Carolina and Virginia. Bloomberg explained that low pressure in the Pacific Northwest and northeast pinned the heat in the central US for the last several weeks.

By mid-June, nearly one-third of the US population was under a heat advisory.

The scorching-hot weather over the Midwest grain belt couldn’t have come at a worse time for grain farmers and buyers. The high temperatures and lack of rainfall are occurring during corn’s pollination period. The prospect of lower yields pushed Chicago corn futures to their highest in nearly a year, Monday.

Europe

In continental Europe and the UK, extreme heat is also taking a toll. The United Kingdom’s national weather service, the Met Office, on Sunday issued an extreme weather warning, as temperatures climbed to 32 degrees C, Monday. The rare alert (it has only been issued twice before) covers large parts of England and Wales. It advises people to stay indoors where possible and to drink plenty of fluids.

A high-pressure system called the Azores High is responsible for the sweltering heat. The system normally sits off Spain but it has grown larger and pushed northward, bringing higher temperatures to the UK, France and the Iberian peninsula. The BBC said Scotland and Northern Ireland had their hottest days of the year so far on Sunday, with France, Germany and Italy expected to see the heat exceed 40C over the coming weekend.

European annual temperatures have been rising since the 1970s, with 2020 being the warmest year on record.

“When it comes to summer heat, climate change is a complete gamechanger and has already turned what would once have been called exceptional heat into very frequent summer conditions,” The Guardian quoted Dr. Friederike Otto, of Imperial College London.

In 2020 in the UK alone, more than 2,500 people died from extreme heat. Heat is especially dangerous when it lasts several days and the temperature does not drop very much at night, to allow for a comfortable sleep. Heatstroke and dehydration are the main risks to health, particularly for young children and the elderly.

Climate scientists have linked heatwaves to weather patterns that produce persistent high pressure, cloud-free conditions and dry continental winds during summer.

“Climate change is intensifying these heatwaves as greenhouse gas increases raise temperatures and a warmer, more thirsty atmosphere dries out the soil, so that more of the sun’s energy is available to heat the ground rather than evaporating water,” said Prof. Richard Allan, of the University of Reading, in The Guardian article.

Another scientist said London is expected to feel like Barcelona by 2050.

The European heat wave is not only making it difficult for people to cope, it’s worsening the continent’s energy crisis. The war in Ukraine had already restricted natural gas supplies from Russia, Europe’s main energy source, driving electricity prices to record highs.

The stifling heat and lack of rain is drying up waterways and boosting demand for electricity, to cool homes. In parts of Italy a severe drought is cutting power supplies and hitting agriculture, Bloomberg said:

Day-ahead power in Britain reached £197.90 per megawatt hour Friday, the highest price for electricity delivered during a weekend since April. French day-ahead power prices rose to 148.62 euros per megawatt hour.

Hot and dry weather has already been adding extra stress to Europe’s power production. Electricite de France SA said it may have to cut output at some of its nuclear power plants, as the ongoing drought reduces river water needed for cooling. Hydro plants in Italy and Spain have also seen a drop in production due to the hot and dry conditions

that we can see in the forecast.”

Like in the United States, the searing heat is baking corn crops, just as they enter their key pollination phase. Paris corn futures rose as much as 6.6% Friday, for the biggest intra-day gain in a month.

Rivers in western Europe are dwindling to dangerously low levels, during a time when the EU is attempting to reduce its dependence on Russian gas partly by substituting it for coal.

According to The Guardian, the Rhine is at its lowest seasonal level in 15 years, with barges unable to load coal at full capacity for power plants in Germany. The nation plans to import 10 million more tons of thermal coal than usual this year, to help power it through winter. Low points in the 1,288-km river, which runs from Switzerland to the North Sea, are occurring at Kaub, near Frankfurt, and in Duisburg and Dusseldorf. Another problem is low barge capacity, with many barges sold in recent years amid a planned coal phase-out.

Meanwhile Italy’s longest river, the Po, has completely disappeared in some places, with northern Italy facing its worst drought in 70 years. In other parts of the river, water levels have dropped eight meters, exposing boats sunk during World War II.

Normally this time of year the river is full, but the mountains that feed it only received a third of the average snowfall last winter.

A state of emergency has been declared in five northern regions, with power stations and spas closed, ornamental fountains in Milan turned off, and daytime watering restrictions in place.

The Guardian reports the Adriatic Sea has come about 12 miles inland from the Po estuary, burning crops and salinating drinking water. Hundreds of thousands of hectares in the Po basin are fallow this summer because of doubts about the reliability of irrigation for the second planting. Even the world-famous cheese, Parmigiano Reggiano, is being affected. The drought has damaged crops needed to feed cows and high temperatures have stressed the herd, reducing the amount of milk they produce, Sky News said.

Last Saturday, 11 hikers were killed in an avalanche when the largest glacier in the Dolomites collapsed, sending 260,000 cubic meters of snow hurtling down the mountain at over 300 km/h. It’s believed a warm winter combined with less snow and the current heatwave led to a huge chunk of the Marmolada glacier breaking off.

China

Asia is also sweltering, more so than it normally does this time of year. It’s been so hot in dozens of Chinese cities, including Shanghai and Beijing, that roads have buckled, roof tiles have popped off, and people are seeking cooler temperatures in air raid shelters underground.

Reuters reported on Monday that 86 cities issued red alerts, the highest in a three-tier warning system, warning of temperatures over 40C in the next 24 hours.

It’s not only the heat that Chinese citizens have to worry about; melting glaciers have raised concerns about the source of new pandemics. According to Ancient Origins, a website about the latest archaeological findings, Chinese geneticists from Lanzhou University have been studying microbial life forms found trapped in glaciers that currently cover the Tibetan Plateau. After completing their analysis, they were shocked to discover 968 new species and bacteria and other tiny life forms that had never been seen before anywhere on Earth.

India

Severe heat has been reported over large parts of India since summer began in March. According to Indian Express, a total of 146 instances of heat wave/ severe conditions were recorded in April, the most since 2010. The average high for the country last month was 35.05, 1.12 degrees higher than normal and the fourth highest average since 1900.

New Delhi has recorded a daily maximum of 42 degrees this summer, reaching 49 in some parts of the capital.

While India is no stranger to heatwaves, often experiencing days of intense hot weather ahead of the monsoon season that provides needed rains, this one has been different.

“This heatwave is quite unusual,” Aditi Mukherji, a principal researcher at the International Water Management Institute out of New Delhi, told CBC News. “Heat waves are common in India, but never so early. Then, heat waves are [normally] localized, but this time, it is widespread almost all across [the country].”

A recent study found that climate change made the heatwave in India and Pakistan 30 times more likely.

Along with discomfort and a spike in electricity usage, causing blackouts, the heat wave has also hit India’s agricultural sector hard. The monsoon rainfall last month ran 32% below normal, and the high heat on top of that scorched the wheat crop. The country is the world’s eighth-largest wheat exporter. Power shortages not only restrict farmers’ ability to cool themselves; they also reduce the availability of electricity to irrigate fields with electric tube wells and pumps. The result is more hardship to a sector already in bad shape.

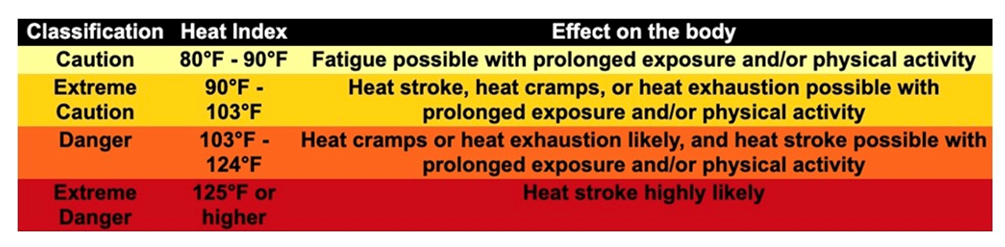

Wet bulb temperature rating

People are generally comfortable living and working in temperatures up to about 80 degrees Fahrenheit. The heat index is what the temperature feels like when relative humidity is combined with relative humidity. Between 80 and 90 degrees F, fatigue is possible with prolonged exposure and/or physical activity. From 90 to 103, heat stroke, heat cramps or heat exhaustion are possible. The danger zone is entered @ temperatures between 103 and 124, with extreme danger happening when it gets to 125 F (51 Celsius) or higher.

In fact, our current heat measurements may be underestimating the dangers of extreme heat to the human body. Meteorologists are therefore turning to the “wet bulb globe temperature” for a more accurate reading.

Basically a more nuanced version of the heat index, the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) takes into account not only the air temp and humidity, but the wind speed, sun angle and solar radiation levels.

Between 80 and 88 degrees Fahrenheit WBGT, working in the sun for more than 45 minutes put the body under serious stress. About 88 WBGT, the window of safety closes to 20 minutes. Above 90, being active in the heat becomes dangerous after 15 minutes, and reaches a point in the 90s where you shouldn’t be doing anything outside.

This is because, above a certain WBGT, the human body loses the ability to cool itself down. The body’s normal cooling mechanism, the way it sheds heat, is by sweating. The upper level of sweaty skin is about 95 WBGT; beyond that, skin loses the ability to carry heat from the body and evaporate it through sweat. Wet bulb temperatures above 95 (35C) are therefore extremely dangerous, and sustained temperatures above 98 (36.6C) are considered fatal. The body literally cooks to death from within.

It was previously thought that wet bulb temperatures very rarely exceeded 91 degrees F, but a 2020 study quoted by Popular Science found that this point has been crossed many times. Among the regions that have experienced this kind of heat, are South Asia, the coastal Middle East, and coastal southwestern North America.

Conditions once experienced only in saunas and deep mineshafts are becoming common for millions of people. After a few hours of humid heat above 35C, the wet bulb temperature threshold, even healthy people with unlimited shade and water could die of heatstroke.

According to Bloomberg, each year we are getting closer to the tipping point where large swaths of the population are exposed to dangerous humid heat temperatures. A doctoral student at Columbia University who studied the phenomenon three years ago found that, far from being part of a future climate apocalypse, humid heat above 35C was already happening, from the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea to Pakistan, India, Australia, Venezuela, and each coast of Mexico.

For example New Delhi reached the wet-bulb threshold several times between May 24 and June 1, 2022, along with Odisha, an eastern Indian state, from May 16-17, May 22-23 and June 5-12.

Bloomberg makes the following additional points regarding extreme heat in India and elsewhere (edited for brevity and clarity):

- A major heatwave just a few degrees higher than those seen in India over the past two months might not just kill tens, even hundreds of thousands — it could also overload electricity grids, cause power plants to shut down, make harvests fail, and hamper the ability of affected economies to grow. May’s heat caused India to cut its forecast for annual wheat production by about 6 million metric tons, putting further pressure on a global trade already disrupted by the war in Ukraine.

- Many of the worst-affected areas are in South Asia, where over a billion people live and less than 10% have access to air-conditioning that could be life-saving in a serious heatwave. Many of them work in agriculture or informal jobs where there’s no shelter from extreme daytime heat.

- Half of households in India and three-quarters in Pakistan still won’t be able to afford air-conditioning by 2050, according to one estimate last year. Powering them requires fast-growing volumes of electricity, which in India is provided mainly by fossil fuels.

- The demand has already caused rolling power cuts in India in recent months, with 60% of homes facing outages during some of the hottest days this May. There’s also the fact that thermal power plants need to cool themselves down, a challenge that gets harder as the wet-bulb temperature rises.

- By the second half of this century, swaths of the tropics and sub-tropics could be seeing months at a time above the highest recorded wet-bulb temperatures.

- At present, around 89,000 people are estimated to die every year in India from hot temperatures — perhaps surprisingly, fewer than the 632,000 who die from cold. With 4C of global warming, heat deaths will rise to 1.5 million a year.

- Villagers in Rasmai have been waking at 4 a.m. to avoid working in the hottest part of the day, and bathing their livestock to keep them alive.

Deadpools

We’ve already explained how droughts, lack of rainfall and scorching temperatures, have caused water levels in two of Europe’s most important rivers, the Rhine and the Po, to fall dramatically. Turns out there is more to say about this phenomenon.

Lake Mead, America’s largest manmade reservoir, and a source of water for millions, just fell to an unprecedented low. Mead has been shrinking amid a +20-year mega-drought (it’s actually the worst drought in 1,200 years) and is currently just one-third full. The most recent measurement on July 7 showed the lake at 1,042 feet, almost 200 feet lower than full capacity and below the 1,050 feet needed to generate power at the Hoover Dam. Power is still being generated, but according to the Bureau of Reclamation, every foot of lake level decline means about 6 megawatts of lost capacity.

The lake level is so low, a landing craft from the Second World War recently became visible. According to the Associated Press, via Global News, the vehicle was originally 185 feet, about 56m, under the surface, but is now sticking half way out of the water.

Anyone can see how much the lake has receded by observing the “bathtub rings” on the cliffs above. The alarmingly low levels could form a “deadpool” if they reach below 895 feet, which is the point where there isn’t enough water left in the reservoir to generate hydroelectric power and for the water to flow downstream. At current lake levels, a deadpool situation is less than 200 feet away.

Once the reservoir drops to 950 feet, the intakes for the dam will no longer be under water and the turbines will stop.

Last August a water shortage was declared at Lake Mead for the first time, cutting water releases to Nevada, Arizona and Mexico, and triggering water conservation measures in those states. The Bureau of Land Management predicts Lake Mead could drop another 30 feet below its current level by September 2023.

The city of Phoenix last Friday said it will forfeit delivery of an additional 14,000 acre-feet, or 4.5 billion gallons, of Colorado River water, to shore up Lake Mead. This brings the total amount of water the city has left in the reservoir so far this year to 9.7 billion gallons, says ABC News.

The Colorado River which feeds Lake Mead has been in a drought for over a decade, with the river basin experiencing below-average rainfall for 16 consecutive years. If current trend continues, Lake Mead will be dry within two decades (World Atlas).

Federal officials are calling on Wyoming and basin states to voluntarily reduce their water consumption, by 2-4 million acre-feet, to protect critical levels in lakes Mead and Powell in 2023. (an acre-foot is the amount of water needed to cover one acre of land with a foot of water). The US Bureau of Reclamation is giving the states until mid-August to come up with a water reduction plan, but if they are unable to, the bureau “is going to step in and do it for us,” said Jeff Cowley, the State Engineer’s Office administrator of interstate streams, in an article by Cowboy State Daily.

Wyoming’s average use of upper basin water has been about 600,000 acre-feet, with agriculture by far the largest user, accounting for about 83% percent of the annual usage.

In fact the problem of lakes drying out, impacting water supplies, is far more widespread than just Lake Mead.

According to World Atlas, over 200 small lakes in the US have dried up within the past two decades. The reason is a combination of drought conditions, increased demand for water and changing precipitation patterns. Dried-up lakes not only affect power generation but threaten fish populations as their habitats disappear, along with wetland habitats, important for migrating birds and other wildlife.

Besides the well-publicized diminishment of Lake Mead, two lesser-known major US lakes that are losing volume, are Walker Lake in Nevada, and Great Salt Lake, Utah.

Once vast and deep, Walker Lake “is now a shadow of its former self, and scientists believe it could be completely dry within the next two decades,” states World Atlas. The main reason is not enough water flowing into it to replace what is being lost through evaporation.

NASA’s Earth Observatory notes the amount of water evaporating worldwide “is significantly more than previously thought.” A new NASA-funded study that measured the surface areas of 1.42 million natural and artificial lakes (reservoirs), found that annually, about 1,500 cubic kilometers of water are lost worldwide to evaporation — the equivalent of three Lake Eries.

Researchers also found the rate of water loss accelerated by 3.12 cubic km between 1985 and 2018, with the increasing volume loss driven by three factors, all influenced by global warming: an increase in the evaporation rate; a decrease in ice cover; and increase in lake surface areas, including the construction of new reservoirs.

Utah’s Great Salt Lake is drying up for a different set of reasons — for one, the lake’s tributaries have been diverted for irrigation and other uses. Number two is the US Southwest’s “driest 22-year period in at least 12 centuries.” According to US Drought Monitor, 99% of Utah is either in “severe” or extreme drought (Bloomberg).

Here we see the relationship between droughts, heat and water loss.

The snowpack recharging the lake is reducing, with research showing that snow cover in the mountains around the lake is melting at least a week earlier than it did 20 years ago.

All of the above has caused the water level to drop by about four feet since 2016, with the lake now at its lowest point since measurements began in 1875. Great Salt’s surface area has also shrunk considerably, to about 950 square miles, less than a third of the 3,300 recorded in 1987. The lake is the largest water body in the US after the Great Lakes.

As the lake level falls, residents of Salt Lake City, and a chain of towns containing more than 2.5 million people who draw water from it, could be in big trouble — demand is set to exceed supply in 2040.

Conclusion

The effects of climate change are becoming more dramatic every year.

The planet isn’t just warming, it’s getting hotter, affecting our weather, oceans, growing seasons, even our food, as crops fail, causing shortages and price hikes. Storms are becoming more frequent, and more intense, and droughts are lasting longer. Forest fires are an annual occurrence in Australia, California and British Columbia. In the United States and the Caribbean, people live in fear of the next hurricane that could literally turn their lives upside down. Most of us have watched videos of calving glaciers as huge chunks of ice break off millions-year-old ice sheets and tumble into the sea.

Some of the most important rivers in the western United States are getting alarmingly low, thanks to a mega-drought that has lasted over 20 years. The Southwestern US is the driest it’s been in 1,200 years. This has knock-on effects that go far beyond the bathtub rings seen on the cliffs above Lake Mead. Higher temperatures caused in whole or in part by global warming, have reduced precipitation in the mountains feeding these massive reservoirs that generate power for millions. The reduced annual snowpack and runoff means the lake levels keep dropping. Without serious conservation measures, Lake Mead is expected to completely dry up within 20 years, stopping the Hoover Dam. When, not if, this happens, the region will be plunged into an energy crisis as well as a climate crisis.

As for Utah’s Great Salt Lake, water demand is set to exceed supply in 2040. A combination of drought and the diversion of its tributaries to irrigation, has significantly diminished the largest body of water in the US besides the Great Lakes, threatening more than 2.5 million people who draw water from it.

Meanwhile, the equivalent of three Lake Eries worldwide, are lost annually to evaporation, made that much worse by climate change.

The annual rise in temperatures, which as this article has demonstrated, is global, is getting downright scary. Heat records have been smashed in the south-central United States, the UK, Europe, China and India. And we’re only half-way through summer.

The heat affects everything, from how much fresh water is available, to irrigation (in India 95% of the water supply is used for this purpose, leaving precious little for everyone else), to power generation, to food production.

As we discussed in a previous article, human-caused degradation of land, including unsustainable farming, overgrazing, clear-cutting, mis-use of water, and industrial activities, have spoiled a quarter of the planet’s inhabitable land since the early 1980s. These processes have all been made worse by global warming. Why is that important? Because according to Luc Gnacadja, executive secretary of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), “The top 20 cm of soil is all that stands between us and extinction.”

The United Nations has declared soil finite, and predicts catastrophic loss within 60 years. According to the UNCCD, the impact of soil degradation could total $23 trillion in losses of food, ecosystems and income worldwide by 2050.

The world relies on soil for 95% of food production, but the UN (via CNBC) says soil erosion could reduce up to 10% of crop yields by mid-century. This is the equivalent of removing millions of acres of farmland.

Climate change accelerates desertification because warmer temperatures dry out once-fertile land, which then makes the area even hotter. Removing plants from the ground also increases greenhouse gas emissions, since they can no longer serve as carbon sinks. As we strip away the amount of available land for food production, we are literally depriving ourselves of the means to survive. Eventually this will lead to the destruction of human civilization.

Since we’re on a roll, there are other consequences from the heat, made worse by “feedback loops” such as melting sea ice, and thawing permafrost in Arctic regions that exposes methane.

The warming of the Earth’s surface has caused widespread melting of mountain glaciers and polar ice. Ice sheets are primarily responsible for the increase in sea level rise since the 1990s. There is also less free-floating ice coverage at the north pole. September Arctic sea ice is now declining at a rate of 13% per decade, relative to the 1981 to 2010 average.

Over the last decade, global average sea levels have risen about 4 mm per year. According to The Conversation, referring to the latest IPCC report, sea level change through 2050 “is largely locked in”. That means, no matter how quickly countries can lower carbon emissions, the seas will rise by between 6 and 12 inches (15-30 cm) by mid-century.

The expansion of ocean water as it warms also causes higher sea levels. An increase of 65 centimeters, or roughly two feet, is expected to cause significant flooding in coastal cities.

As ice melts during the summer, the Arctic Ocean warms. That heat gets radiated back to the atmosphere in winter, which reduces the intensity of the northern polar vortex winds. The polar vortex gets disrupted, allowing cold air in the center of the swirling cyclone above the pole to migrate south, resulting in meteorological aberrations like snowfalls in Florida.

While occasional breakdowns of the polar vortex are nothing to be concerned about, they are becoming more common. A study in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society found that a weakening polar vortex has become more common during the past four decades.

The scary part of all this is the spectre of the polar vortex collapsing. This would mean a total disruption of normal atmospheric warming and cooling. Without halos of swirling Arctic and Antarctic winds serving to cool the poles, they would be left to heat up, accelerating global warming.

Climate scientists have also been raising concerns that rising temperatures could throw a wrench into the conveyor-like currents system. Sensors stationed along the North Atlantic show that the volume of water moving northward has been sluggish, potentially affecting sea levels and weather.

It’s important to understand what a rapidly warming world means for human health.

Above a certain wet bulb globe temperature, WBGT, the human body loses the ability to cool itself down. The body’s normal cooling mechanism, the way it sheds heat, is by sweating. The upper level of sweaty skin is about 95 WBGT; beyond that, skin loses the ability to carry heat from the body and evaporate it through sweat. Wet bulb temperatures above 95 are therefore extremely dangerous, and sustained temperatures above 98 are considered fatal. The body literally cooks to death from within.

Between extreme heat, droughts and a lack of fresh water, areas of planet Earth may soon become inhabitable, putting an even greater strain on existing finite natural resources, and increasing competition for them.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.