Let them eat cake

2022.06.08

Dirt. We spit on it, kick it off our shoes, wash it from our pets. But in the end, what’s more important than soil needed to grow our food?

Human-caused degradation of land, including unsustainable farming, overgrazing, clear-cutting, mis-use of water, and industrial activities, have spoiled a quarter of the planet’s inhabitable land since the early 1980s. These processes have all been made worse by global warming. Why is that important? Because according to Luc Gnacadja, executive secretary of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), “The top 20 cm of soil is all that stands between us and extinction.”

Desertification

Broadly speaking, desertification refers to the process of turning arable land into desert usually as a result of deforestation, drought or harmful agricultural practices. Removing vegetation also takes away nutrients from the soil, making the land unsuitable for farming. According to the UNCCD, around 12 million hectares of productive land become barren every year as a result of desertification and drought.

Climate change accelerates desertification because warmer temperatures dry out once-fertile land, which then makes the area even hotter. Removing plants from the ground also increases greenhouse gas emissions, since they can no longer serve as carbon sinks.

A study quoted in The Independent shows that up to 30% of the world’s land surface would become arid if temperatures rise 2° Celsius above pre-industrial levels. We are already at 1.1 degrees.

Desertification is not only bad ecologically, it can also lead to global tensions. Land conflicts in Somalia, dust storms in Asia and food price crises (in Mozambique, Egypt, Serbia and Pakistan) have all been attributed to desertification. The Arab Spring of 2010-11 was sparked by a spike in grain prices a couple of years earlier which meant a 37% rise in the price of bread. Bread in Egypt is called “aish”, or life.

As we strip away the amount of available land for food production,

we are literally depriving ourselves of the means to survive. Eventually this will lead to the destruction of human civilization — just as desertification contributed to the collapse of the world’s earliest known empire, the Akkadians of Mesopotamia.

Global soil shortage

Ukraine is known as the “breadbasket of Europe” because it contains some of the most fertile soil in the world. Called chernozem, this soil was formed from fine mineral particles that, millions of years ago, were carried by winds from ancient glacial beds. The winds acted as a kind of massive filter, meaning that Ukraine’s chernozem is virtually without rocks, making it ideal for agriculture.

Good soil is often termed “black gold”, but we are running out of it.

The United Nations has declared soil finite, and predicts catastrophic loss within 60 years. According to the UNCCD, the impact of soil degradation could total $23 trillion in losses of food, ecosystems and income worldwide by 2050.

The world relies on soil for 95% of food production, but the UN (via CNBC) says soil erosion could reduce up to 10% of crop yields by mid-century. This is the equivalent of removing millions of acres of farmland.

Jo Handelsman, the former science advisor to President Barack Obama, says the world may be on the edge of unprecedented crop loss and food shortages if soil erosion continues to intensify.

In her recent book, Handelsman notes South America is likely to incur the largest increase in erosion rates in the next decade. Already, 68% of the continent’s soil is affected, with 640 million acres deforested, 172 million acres overgrazed by livestock, and as much as half the land in Argentina and Paraguay damaged by desertification.

In Bolivia, up to 6.4% of its drylands are annually eroding between 55 and 551 tons of soil per 2.5 acres; if this continues, Handelsman says the land will be unfit for agriculture within a few years. Brazil is also in bad shape, with demand for bioenergy crops, agricultural exports and climate change all fueling erosion. She cites satellite images showing vast tracts of pastures replaced with soybeans, sugarcane and maize — three crops that are responsible for an estimated 28% of Brazil’s soil erosion caused by agricultural activity. Some Brazilian states are already paying in excess of $200 million annually to address soil loss.(‘Erosion Poised to Cause Unprecedented Food Shortages Worldwide’, No-Till Farmer, Nov. 24, 2021)

The Earth is thought to lose roughly 23 billion tons of fertile soil every year. At this rate, all fertile soil will be gone within 150 years, unless farmers convert to sustainable farming methods (see section below).

One source said by 2060, our soils will be forced to provide as much food as we have consumed in the last 500 years, whereas, around half of the topsoil on the planet has been lost in the last 150 years.

When soil is removed, it not only threatens the food supply, but fresh water and biodiversity.

“Soil is the habitat for over a quarter of the planet’s biodiversity. Each gram of soil contains millions of cells of bacteria and fungi that play a very important role in all ecosystem services,” Reza Afshar, chief scientist at the regenerative agriculture research farm at the Rodale Institute, told CNBC.

Soil is not only necessary for producing food, it is also a great reservoir for sequestering carbon, and makes groundwater safe from contaminants. According to The Statesman, When soil is lost or eroded, we lose not only food and levels of carbon sequestration and biodiversity, but our groundwater sources also begin to degrade.

No-till farming

So far we have attributed soil loss/ degradation to agricultural exports, deforestation, excessive use of synthetic fertilizers, demand for bioenergy crops like corn, and climate change. But there is another contributor to this phenomenon, and that is the lowly plow.

Tilling the soil is an ancient farming practice that involves turning over the first six to 10 inches of soil before planting new crops. On the plus side, tilling works surface crop residue, animal waste and weeds deep into the fields, aerating and warming the soil. It also allows farmers to plant more seeds while expending less effort and wages.

In the long run, however, tilling does more harm than good. Undisturbed soil is like a sponge, that when disturbed by tilling, becomes less able to absorb water and nutrients. When soil is plowed, it loosens and removes plant matter covering the soil, leaving it bare. Bare soil stripped of its nutrients is more likely than undisturbed soil, to be eroded by wind and water.

Tilling also displaces or kills the millions of microbes and insects that form healthy soil biology, leading Regeneration International, a non-profit group, to conclude, The long-term use of deep tillage can convert healthy soil into a lifeless growing medium dependent on chemical inputs for productivity.

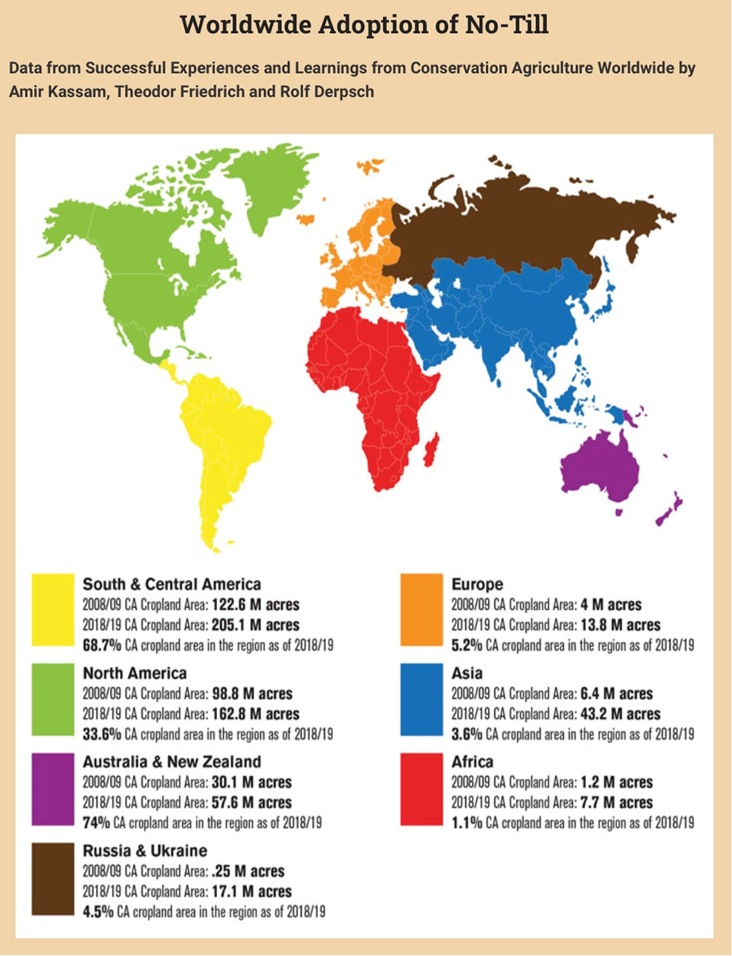

Fortunately, there is a movement afoot to farm more sustainably, thus preserving valuable topsoil. It’s called no-till farming, and it’s catching on. According to No-Till Farmer, a recent study found 507.6 million no-till acres exist worldwide, a massive increase since 2008-09.

The number of no-till acres worldwide has increased by 93% in 10 years, bringing the total number to 507.6 million acres.

Supporters of the practice say it allows soil structure to stay intact and protects the soil by leaving crop residue on the surface. No-till also slows evaporation, meaning that rainwater is better absorbed, and irrigation is more efficient, leading to higher yields.

Modern no-till tractor implements reportedly allow farmers to sow seeds faster than cheaper than if they tilled their fields. Of course, leaving out the step of tilling also saves the farmer time and money, with one report stating that the no-till method decreases fuel expenses by up to 80% and labor costs up to 50%.

However, while no-till agriculture is growing, at a rate of about 25 million acres per year, it currently only makes up about 14.7% of global cropland. Arguably, to reverse the global soil-loss trend, much more needs to be saved from the plow.

Rob Derpsch, a long-time no-till researcher, believes that all farmland needs to be conservation cropland (the term used for no-tillage outside North America) for society to continue to exist.

This is a shocking assertion. Should we be worried?

Well, if we summarize what we already know is happening regarding the global food supply — including war, drought, fresh water depletion, climate change, desertification, resource nationalism, and now soil loss — it does paint a very dystopian picture.

Developing food crisis

Food prices are rising at a rate beyond anyone’s imagination.

The Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) food price index, which tracks the price movements of the most commonly traded and consumed food crops, recently reached its highest on record.

Most attribute the exorbitant prices, like with many other commodities (i.e. oil, natural gas), to the ongoing war in central Europe, which has caused disruptions to the global supply chain. Indeed, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February triggered a series of events that blocked off some of the region’s supply routes, taking away a significant portion of the world’s food supply. The result? Practically every category we consume — wheat, meat, dairy products, etc. — got more expensive.

The Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index jumped 1.9% on Monday, hitting a fresh record high. Growth in the index, which tracks the prices of 23 raw materials, was mostly driven by fears over whether there will be adequate supplies of natural gas and wheat.

FAO economists estimate that Russia and Ukraine together provided around 30% of the global wheat supply and 20% of maize exports over the past three years. It’s been ballparked that nearly 25 million tonnes of grain have been eliminated from the supply chain since Russia’s blockade of Ukrainian ports.

Complicating food inflation, is excessive government intervention in the food supply. For example, many countries have a deficit of cereal production because of an unsustainable level of restrictions that have made it impossible for farmers to continue planting and producing grain. In a column, economist and fund manager Daniel Lacalle writes:

Governments around the world should have learnt from these previous experiences and eased the administrative and tax burdens on farming to allow the market to provide flexibility in times of supply concerns from one or two nations. Instead, we have seen more rigidity, taxes and higher restrictions that have limited the possibility of easing supply chain issues.

Also contributing to the higher food prices is the scarcity of fertilizers, that farmers rely on to keep their corn, soy, rice and wheat yields high.

Western sanctions against Russia and neighboring Belarus essentially placed a sizable share of the world’s available fertilizer off-limits.

Together, Russia and Belarus accounted for more than 40% of global exports of potash last year, one of three critical nutrients used to boost crop yields, according to Morgan Stanley.

With reduced shipments, prices of this key farming input eventually soared to record highs, surpassing levels last seen during the food and energy crisis of 2008. According to British commodity consultancy CRU, prices for raw materials that constitute the fertilizer market — ammonia, nitrogen, nitrates, phosphates, potash and sulphates — are up 30% since the turn of the year.

Commenting on the global shortage of fertilizers, World Farmers’ Organization President Theo de Jager recently said: “Prices are more or less 78% higher than average in 2021, and this is cracking up the production side of agriculture. In many regions, farmers simply can’t afford to bring fertilizers to the farm, or even if they could, the fertilizers are not available to them.”

“And it’s not just fertilizers, but agrichemicals and fuel as well. This is a global crisis and it requires a global response,” de Jager added.

Back in March, FAO chief economist Maximo Torero said “the fertilizer crisis is in some respects more worrying because it could inhibit food production in the rest of the world that could help take up the slack.”

The United Nations and other international organizations have warned that more costly food could upend the global economy, creating widespread hunger in vulnerable countries such as those in Africa and the Middle East.

Even before the Russian invasion, fertilizer costs were soaring as record energy prices forced makers of the nutrient to cut production. In turn, global food production fell well below its target, and food prices, which have been rising precipitously over the course of the covid-19 pandemic, got more expensive and, in some places, unaffordable.

In its latest report highlighting the severity of the crisis, the UN estimates that in the past year, global food prices have risen by almost one-third, fertilizer by more than half and oil prices by almost two-thirds.

The UN report also revealed that the number of severely food-insecure people has doubled over the past two years, from 135 million pre-pandemic to 276 million today. More than half a million people are now experiencing famine conditions, according to UN figures, representing an increase of more than 500% since 2016.

In Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya, the number of people facing extreme hunger has more than doubled since last year, the UN noted.

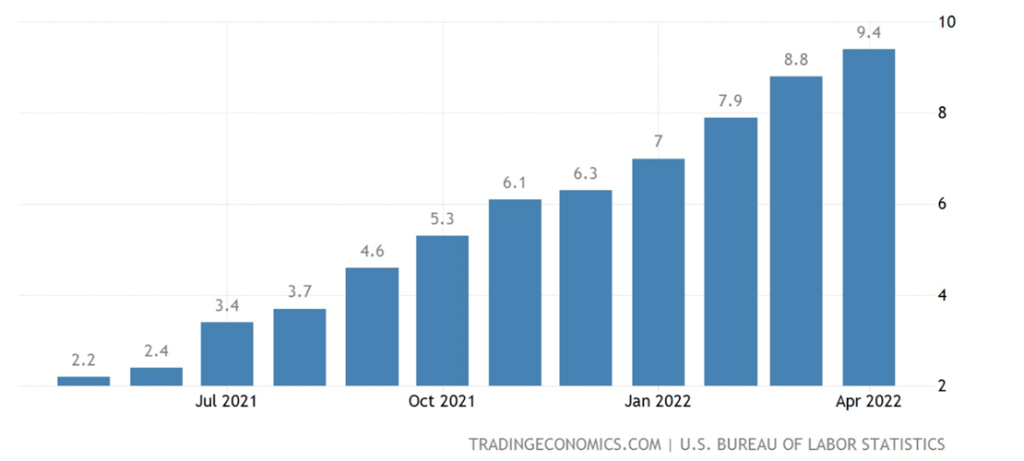

US food costs were up 9.4% during the month of April, with prices for meats, poultry, fish and eggs up 14.3% from the previous year, Labor Department data showed. In China, prices of fresh vegetables are 24% higher than a year ago, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

In Canada, a recent poll found that hunger and food insecurity are increasing as grocery prices continue to climb. The survey by Food Banks Canada reported nearly a quarter of Canadians are eating less than they should because of not having enough money for food. The figure doubled for those earning less than CAD$50,000 per year.

Compounding the global food crisis is the continued threat of extreme weather, which, according to the World Food Programme, contributed to most of the world’s food crisis two years ago and was the primary cause of acute food insecurity in 15 countries.

Higher temperatures, water scarcity, droughts, floods, and greater CO2 concentrations all negatively impact the yields of staple crops.

According to the UN, demand for water is expected to grow 55% by 2050, with most of the need (70%) driven by irrigation, to feed the expanding global population, expected to hit 10 billion by 2050. Water for energy use is forecast to rise by 20%.

The supply won’t be enough to satisfy everyone. By 2025, 1.8 billion people will live in areas where water is scarce, and two-thirds will be residents in water-stressed regions, reports National Geographic.

The FAO estimates that 80% of the causes behind an unpredictable harvest for cereal crops in areas like Africa’s Sahel come down to climate variability. In Bangladesh and Vietnam, rising sea levels are jeopardizing the world’s rice supply by flooding farmland with saltwater.

Since the 1990s, the number of weather-related disasters around the world has doubled, a pattern that has greatly increased the risk of food insecurity and higher food prices. Sadly, this trend is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

Recently India announced a ban on its wheat exports amid an intense heat wave that saw temperatures hitting a record 49.2 degrees Celsius. The country is the world’s second-largest wheat producer after China.

Heat waves, which are expected to become more frequent and more intense, could cause up to 10 times more crop damage than is currently projected. The United States experienced about $12 billion in crop losses last year, of which 82% was due to drought and wildfires.

Scientists are warning that future temperature will test humas’ ability to survive, with some parts of the planet becoming uninhabitable. The Weather Network explains:

When you’re exposed to prolonged heat, you may feel sluggish because your organs are working harder to keep you cool — and alive.

Your heart beats harder to push blood to your skin, where it can cool down. Sweating is also essential for cooling your body, but it gets harder as humidity increases.

In extreme cases of heat stroke, your body essentially begins to cook, breaking down cells and causing organ damage.

Food protectionism is on the rise in developing countries, as they struggle to cope with higher prices. Around 30 countries have taken measures to restrict food exports since the war in Ukraine began on Feb. 24. The latest is a ban on chicken exports by Malaysia, adding to India’s recent curb on shipments of wheat and sugar. Indonesia has limited palm oil sales, with other nations issuing grain quotas.

Pre-war, the dry weather in Latin America lowered its grain inventory to levels expected to keep grain prices high until 2023, Morgan Stanley analysts recently wrote in a report.

Meanwhile, droughts are impacting food production in Canada and the United States, lowering crop yields, and causing ranchers to cull part of their herds. Lake Mead, America’s largest manmade reservoir, and a source of water for millions, just fell to an unprecedented low.

The fresh water crisis has become so bad in California, that lawmakers want to buy up water rights’ from farmers to stave off drought.

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would on average reduce global yields of wheat by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

Social unrest

Even a shallow understanding of history shows how restricted access to food, and skyrocketing prices of staples like bread, corn and rice, can quickly lead to social unrest. The three basic elements of survival are clean air, fresh water and food. Humans can only last a couple of days without water, and most will starve to death if deprived of food for more than two weeks.

The following events, culled from Wikipedia, are examples:

- Women’s March on Versailles, 1789 —One of the earliest and most significant events of the French Revolution. The march began among women in the marketplaces of Paris who, on the morning of 5 October 1789, were near rioting over the high price and scarcity of bread. Their demonstrations quickly became intertwined with the activities of revolutionaries who were seeking liberal political reforms and a constitutional monarchy for France. Marie Antointette’s famous “let them eat cake”, upon being told that peasants had no bread, led to the guillotine.

- Potato Riots, 1834 and 1840-44 — Mass anti-serfdom- movement of peasants in the Russian Empire.

- Ireland’s Great Famine — Several food riots took place, for example, in Dungarvan in 1846 and at Bantry in 1847.

- Flour Riot, 1837 — In New York City, hungry workers plundered storerooms filled with sacks of hoarded flour, after commodity prices skyrocketed over the winter of 1836-7, fueled by foreign investment and two successive years of wheat crop failures.

- Richmond Bread Riot, 1863 — Food deprivation during the American Civil War was the cause of this, the largest civil disturbance in the Confederacy during the war, in Richmond, Virginia, on April 2, 1863. A Union blockade of Confederate ports prevented food from being imported from other countries. Also, less food was being grown because of the war. As food became scarcer, prices jumped. Encyclopedia Britannica describes what happened on April 2: Led by Mary Jackson, a mother of four, and Minerva Meredith, whom Varina Davis (the wife of President Davis) described as “tall, daring, Amazonian-looking,” the crowd of more than 100 women armed with axes, knives, and other weapons took their grievances to [Gov. John] Letcher on April 2. Letcher listened, but his words failed to pacify the crowd, and the women began marching toward government food storehouses, crying, “Bread! Bread!” and “Bread or blood!” As the group marched, they were joined by additional people brandishing weapons. The original group swelled to hundreds, perhaps thousands, of rioters. The governor called out the public guard, but its forces could not stop the crowd, which broke into government storehouses and nearby businesses, taking whatever they could get their hands on.

- Santiago Meat Riots, 1905 — A violent riot in the Chilean capital Santiago, in October that year, originated from a demonstration against the tariffs applies to cattle imports from Argentina.

- Japan Rice Riots, 1918 — A series of popular disturbances that erupted throughout Japan from July to September 1918, brought about the collapse of the Terauchi Masatake administration.

- West Bengal Food Riots, 2007 — Occurred in West Bengal, India over shortage of food and widespread corruption in the public distribution system.

- Arab Spring, 2011 — Protesters marched from Tunisia to Egypt to Yemen demanding the toppling of their regimes along with freedom, equality, and bread.

- Venezuelan Food Crisis, 2016 and 2017 — The steep fall in oil prices hit the Venezuelan economy hard. With inflation set to top 1,600% in 2017, the decline of Venezuela’s industrial base led to food shortages and economic collapse.

- South African Food Riots, July 2021 — What initially began as protests in response to the arrest of former president Zuma quickly escalated into nationwide looting of supermarkets and shopping malls. The expanded scope of the unrest, that had followed a record economic downturn and increasing unemployment from the covid-19 pandemic, has been described as food riots.

- Sri Lankan Protests, 2022 — Escalated in part due to food shortages and post-covid-19 pandemic inflation.

Corporate control

As if climate change, desertification, soil loss/ degradation, and the war in Ukraine weren’t enough to push food prices to record highs, putting millions of food-insecure people (in both developed and developing countries) at risk of going hungry or dying, there is the issue of who controls the world’s food supply.

According to one source identified by AOTH, the food industry is monopolized by fewer than a dozen companies, and all of them are largely owned by BlackRock and Vanguard. Over the years the monopoly has grown, resulting in food getting both more expensive and less accessible.

BlackRock is a US multi-national investment firm with USD$10 trillion assets under management (AUM). It has been called “the fourth branch of government” because it is the only private firm that has financial agreements to lend money to the central banking system.

Slightly smaller at $7 trillion AUM, the Vanguard Group owns a large portion (about 7%) of Blackrock. Owners and stockholders of Vanguard include Rothschild Investment Corp, Edmond De Rothschild Holding, the Italian Orsini family, the American Bush family, the British Royal family, the du Pont family, and the Morgan, Vanderbilt and Rockefeller families.

With ownership of food companies representing a “who’s who” of America’s financial elite, is it any wonder there is little appetite for reforming the system, say by changing to no-till farming methods to protect topsoil, or converting more fruits and vegetables to organic, thereby cutting fertilizer demand?

Food security is also being undermined by patentable food. The Food and Agriculture Research Act, established in 2014 through the Farm Bill, in 2019 launched a public-private consortium of indoor growers, breeders and genetics companies. The consortium is tasked with advancing speed-breeding, and altering plant chemicals responsible for flavor, nutritional and medicinal value. Lettuce, tomatoes, cilantro, strawberries and blueberries are among the crops being worked on.

Monsanto/Bayer reportedly founded a start-up in 2020 called Unfold, which develops new vegetable seed varieties geared toward vertical farms. GMOs already account for three-quarters of the food that Americans consume, a percentage that will approach 100% once fresh produce is under patent.

There are a number of concerns around genetically modified foods, including allergies, cancers and environmental issues. Farmers have to rely on Monsanto or other large corporations for their seeds every year; they can’t plant perennial seeds like they used to, they have to buy annuals. Over half of the world’s commercial seed market is controlled by just three firms — Monsanto, DuPont and Syngenta.

Conclusion

Research shows the human race is far over-extending itself and if reductions aren’t made or productivity doesn’t improve, it will eventually run out of food, rendering the Green Revolution a failure.

A report from the World Resources Institute concludes that feeding the world’s 9.8 billion in 2050 will require clearing most of the world’s remaining forests. The removal of the world’s carbon sinks would of course result in further warming, increasing the risk of crop failure and mass starvation.

In fact the UN’s often-quoted Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says we need to do precisely the opposite: shrink the amount of emissions-creating farmland and significantly increase the number of trees or other types of vegetation that can act as carbon sinks.

Unfortunately though, we appear no closer to achieving either objective. The planet continues to get hotter and climate change is reducing not only the quantity of food crops but the quality.

Soil erosion could reduce up to 10% of crop yields by mid-century, the equivalent of removing millions of acres of farmland. Remember, “The top 20 cm of soil is all that stands between us and extinction.”

The Earth is thought to lose roughly 23 billion tons of fertile soil every year. At this rate, all fertile soil will be gone within 150 years, unless farmers convert to sustainable farming methods.

But that is unlikely to happen en masse, considering that the food industry is monopolized by fewer than a dozen companies, all of them largely owned by BlackRock and Vanguard. While individual farmers are suffering from higher input costs, like fertilizer, feed and fuel, forcing them to cull herds and plant less, the food companies and some of the richest families in the United States and Europe are raking it in.

The food crisis that is emerging alongside a climate crisis and a fresh water crisis, is sowing the seeds of rebellion among the masses who have no control over food prices, and few if any alternatives. When people are hungry and their kids are crying, they take to the streets. The Jan. 6, 2021 riot in Washington was due to a disputed election. The next major groundswell of public outrage at the skyrocketing cost of living (not just food but gasoline, housing, insurance, etc.) could be much worse. When Marie Antoinette advised the peasants to “eat cake”, she lost her head. Politicians: you have been warned.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.