Tackling the global plastic crisis

2022.02.26

There’s no denying that plastics and plastic packaging have become an integral and important part of the global economy. Plastics are capable of delivering massive economic benefits thanks to their combination of low cost, versatility, durability and high strength-to-weight ratio.

As a key enabler for sectors as diverse as packaging, construction, transportation, healthcare and electronics, plastics are without a question the dominant material of the modern world.

According to a 2016 study titled “The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics” published by the World Economic Forum, the world’s plastic production went from 15 million tonnes in 1964 to 311 million tonnes in 2014 — a twenty-fold increase during a 50-year period.

Production of the synthetic material is expected to at least double again over the next two decades, then quadruple by 2050, the WEF predicts.

The largest application of plastics is packaging, without which many of our consumer products and services would no longer be accessible or viable (see below).

Due to its low cost and weight, as well as barrier properties to keep food fresh, plastics have gradually replaced other packaging materials over the years. The WEF estimates that about 26% of plastics are used for packaging as of 2016, an increase from the 17% recorded in 2010.

According to Transparency Market Research, in 2013, the industry put 78 million tonnes of plastic packaging on the market, with a total value of $260 billion.

“Plastic packaging volumes are expected to continue their strong growth, doubling within 15 years and more than quadrupling by 2050, to 318 million tonnes annually – more than the entire plastics industry today,” the WEF report said.

Drawbacks of Plastic Packaging

While plastic packaging can be seen as the driver of economic value, at the same time, the single-use nature of most plastics today undoubtedly poses quite a few questions for the long-term viability — both economically and, more importantly, environmentally — of the material.

Loss of Material Value

For starters, approximately 95% of plastic packaging material value or $80-120 billion annually is lost to the economy after a short first use.

More than 40 years after the launch of the now omnipresent “recycling” symbol, only 14% of the plastic packaging is collected for recycling, the WEF says. When additional value losses in sorting and reprocessing are factored in, only 5% of material value is actually retained for subsequent use.

For plastics that do get recycled, those are mostly processed into lower-value applications that are not again recyclable after use. The recycling rate for plastics in general is even lower than for plastic packaging, and both are far below the global recycling rates for paper (58%) and iron and steel (70-90%).

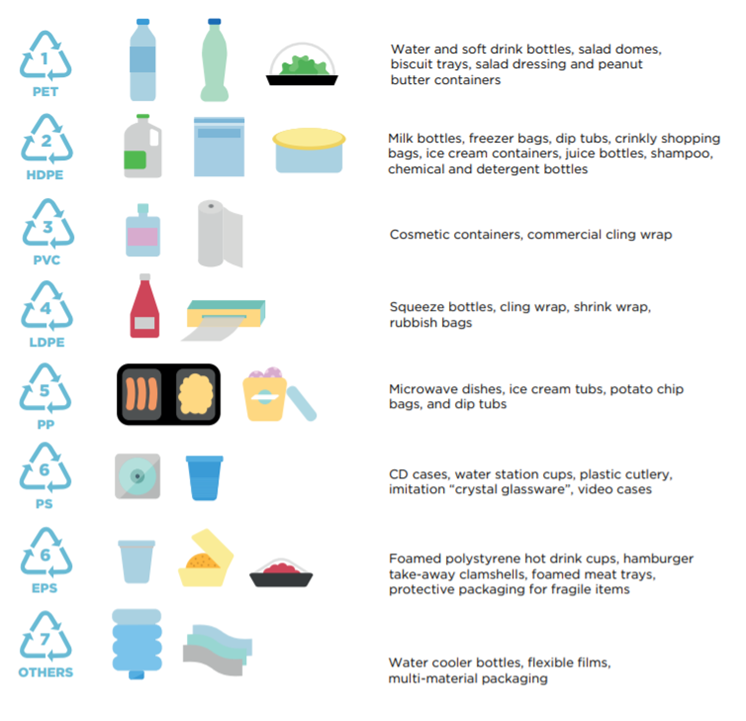

PET, which is used in beverage bottles, has a higher recycling rate than any other type of plastic, but even this is far from a success story. Globally, close to half of PET is still not collected for recycling, and a mere 7% is recycled bottle-to-bottle.

US EPA data shows that the recycling rate of PET was 26% in the United States in 2021, a slight decrease from the year before.

Most importantly, plastic packaging is almost exclusively single-use, especially in business-to-consumer applications. According to the WEF, “an overwhelming 72% of plastic packaging is not recovered at all: 40% is landfilled, and 32% leaks out of the collection system – that is, either it is not collected at all, or it is collected but then illegally dumped or mismanaged.”

Damage to Marine Ecosystems

Perhaps the biggest knock against plastics is their impact on the natural environment.

It’s estimated that a dump truck’s worth of plastic enters our oceans every passing minute; that equates to at least 8 million tonnes of material, most of it being plastic packaging, leaking into the marine ecosystem per year.

This leakage rate could easily increase to two per minute by 2030, and four per minute by 2050, the Ocean Conservancy projects.

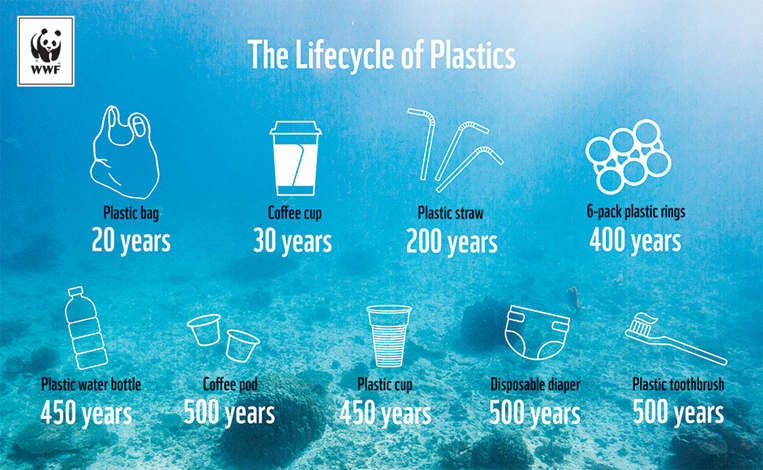

Plastics are able to remain in the ocean for hundreds of years in their original form, and even longer in small particles, which means that the amount of plastic waste in the ocean accumulates over time.

The Ocean Conservancy estimates that there are now over 150 million tonnes of plastic waste in the ocean today. Without significant action, there may be more plastic than fish in the ocean by weight. By 2025, the ratio of plastic to fish in the ocean is expected to be one to three, as plastic stocks in the ocean are forecast to grow to 250 million tonnes, the DC-based environmental advocacy group says.

In its 2017 report titled Stemming the Tide, the Conservancy says “even if concerted abatement efforts would be made to reduce the flow of plastics into the ocean, the volume of plastic waste going into the ocean would stabilize rather than decline.” This implies that there would be a continued increase in total ocean plastics to cause indefinite and, in some cases, irreparable harm to marine habitats.

Given the magnitude of impact and the domino of potentially catastrophic effects, the total economic costs of ocean plastics are still unclear, but studies all suggest it is a massive sum in the billion-dollar ballpark.

Deloitte estimates that marine plastic pollution could have resulted in an economic loss of $19 billion for 87 coastal countries in 2018. Ocean cleanup activities constituted a majority of the costs (~82%).

Deloitte also found that plastic pollution led to $4.3 billion less revenue for the fishing and aquaculture sector, and a reduction in revenue of between $2.4 billion for the tourist trade.

A report by the UN Environment Programme and the Plastics Disclosure Project (PDP) pegs the annual damage of plastics to marine ecosystems at least $13 billion per year. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) estimates that the cost of ocean plastics to the tourism, fishing and shipping industries was $1.3 billion in that region alone.

Even in Europe, where the leakage is relatively limited, potential costs for coastal and beach cleaning could reach €630 million ($695 million) per year, a study by the European Commission suggests.

In addition to the direct economic costs, there are potential adverse impacts on human livelihoods and health, food chains and other essential economic and societal systems, which would make the economic impact much larger than imagined.

Increased Emissions

Ironically, plastics were first discovered behind the idea that they can protect the natural world from the destructive forces of human need. It could help us maintain the availability of natural resources by replacing something that is scarce (i.e. wood, metal) with another whose quantity we are able to control (plastic).

During its use phase (packaging, tools, toys, etc.), plastics are deemed totally harmless to the environment as they cause no greenhouse gas emissions. However, the same cannot be said for the other phases.

Once we take into consideration the processes involved in making plastic and its after-use treatment, the economic and environmental costs could significantly outweigh the intended benefits.

The WEF estimates that about 6% of global oil is devoted to the production and sometimes the after-use pathway of plastics. In 2012, these emissions amounted to approximately 390 million tonnes of CO2 for all plastics (not just packaging).

According to the collaborated study by the UNEP and PDP, the manufacturing of plastic feedstock, including the extraction of the raw materials, gives rise to greenhouse gas emissions with natural capital costs of $23 billion. The production phase, which consumes around half of the fossil feedstocks flowing into the plastics sector, leads to most of these emissions, the report says.

The remaining carbon is captured in the plastic products themselves, and its release in the form of greenhouse gas emissions strongly depends on the products’ after-use pathway. Incineration and energy recovery could result in a direct release of the carbon. When the plastics are landfilled, this feedstock carbon could be considered sequestered, but if leaked, carbon may still be released into the atmosphere over many (potentially, hundreds of) years. According to research, this greenhouse gas footprint will become even more significant given the projected surge in consumption.

If the current strong growth of plastics usage continues as expected, the emission of greenhouse gases by the plastics sector could account for as much as 15% of the global annual carbon budget by 2050, up from 1% at the time of the study, posing a threat to our climate targets.

Health Concerns

Plastics are made from a polymer mixed with a complex blend of additives such as stabilizers, plasticizers and pigments, and might contain unintended substances in the form of impurities and contaminants.

Substances like bisphenol A (BPA) and certain phthalates, which are used as plasticizers in polyvinyl chloride (PVC), have already raised concerns about the risk of adverse effects on human health and the environment.

Furthermore, there are uncertainties about the potential consequences of long-term exposure to other substances found in today’s plastics, their combined effects and the consequences of leakage into the biosphere.

Global Treaty: Future of Plastics

The concerns listed above aren’t going away any time soon. Recent reports suggest that, in absence of a monumental reversal, another 80 million tonnes of plastic could end up in the ocean by 2040. This equates to about half of all the plastic that has been accumulated in the ocean since the plastics era.

The fifth session of the UN Environment Assembly set to take place in Nairobi could prove instrumental in providing a much-needed solution to the “global plastic crisis.”

In the upcoming days, leaders from as many as 193 countries are expected to meet and draft the blueprint of a global treaty to address the issue of plastic pollution. This is being touted as the “most important environmental pact” since the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change.

According to reports, more than 50 countries, including all 27 members of the European Union, are calling for the pact to include measures to reduce plastic production.

This would be bad news for the big, powerful oil and chemical companies, as the industry is projected to double its plastic output within the next two decades.

Some plastic industry groups have expressed public support for a global agreement, and heavy plastics users like Coca-Cola and PepsiCo have said for the first time that they wanted any treaty to curb future production of the material.

However, it’s totally possible that behind the scenes, powerful industry groups will continue to “shift the debate” by making a case for the benefits of using plastic. As revealed by Reuters sources, plastic makers are expected to urge UN delegates to focus on waste collection, recycling and new waste-to-fuel technologies instead.

However, the track record of these efforts tells its own story.

Just 9% of all plastic ever produced has been recycled, with the rest incinerated, dumped in landfills or left to pollute the environment, according to the 2017 study published in Science Advances.

Experts all agree that recycling could never compete with overproduction. Single-use plastic still accounts for around 40% of all production, according to the journal’s landmark 2017 study. Reuters’ investigations last year revealed that some of the industry’s recent recycling projects have made little impact or even shut down.

If the UN cannot agree on a deal that puts the brakes on plastic pollution, there will be widespread ecological damage over the coming decades, putting some marine species at risk of extinction and destroying sensitive ecosystems, according to a WWF study released this month.

As for the public, they are also on board with limiting plastic use. A recent poll by multinational market research firm IPSOS shows that three in four people worldwide want single-use plastics to be banned as soon as possible.

The percentage of people calling for plastic bans is up from 71% since the last poll in 2019, while those who favored products with less plastic packaging rose to 82% from 75%, according to the IPSOS poll of more than 20,000 people across 28 countries.

Solution: Alternatives to Single-Use Plastic

If not apparent already, the world simply cannot recycle its way out of its “plastic crisis” — whether the industry likes it or not, it’s now time for a new approach to how we produce and use plastic.

An insight report published by the WEF finds that the key will be to move from a “linear” waste economy – in which a product’s existence follows a one-way line from manufacture to usage to the landfill (i.e. single-use plastic) – to a “circular” economy in which items are reused or recycled indefinitely.

A system like this that eliminates single-use plastic would not only reduce humanity’s ecological footprint, but also create lucrative opportunities for economic value.

The report laid out three possible scenarios for the development of reuse by 2030 (see above). In the best-case scenario, as much as 26-46 million tonnes would be shifted away from disposables, and plastic waste would be virtually eliminated from our oceans.

According to UNEP data, the world currently produces around 300 million tonnes of plastic waste every year. This figure could easily rise given that plastic production is projected to double by 2040, and less than 10% of all plastic ever made has been recycled.

It is now up to governments, corporations and agencies to consider these scenarios and advance dialogues towards opportunities and innovations that make the plastic we produce to be reusable.

Walmart recently announced it is testing reusable tote bags that can be collected and washed again as part of its direct-to-fridge delivery service. This pilot project, limited to a single store in New York, is part of the retail giant’s broader effort to deliver on a pledge to move toward reusable, recyclable or industrially compostable packaging for its private brands and reach zero waste in its North American operations by 2025.

The results so far have been quite successful. Mike Newman, CEO of Returnity, which makes the tote bags, told CNBC that the bag return rate was nearly 100%. “For the model to work, reusable packaging must make sense financially. That means packaging that is used frequently, designed with recycled plastics or other sustainable materials, with a return rate of more than 92%,” Newman said.

In Canada, the Vancouver-based Evanesce Packaging Solutions Inc. is looking to develop plant-based compostable packaging alternatives that can decompose in 90 days or less, which would leave significantly less footprint than single-use plastic, which can take 500 years or even longer to decompose.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks.

Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.