Plastic pollution: a scourge with far-reaching consequences – Richard Mills

2024.03.14

Every day most of us contribute, several times, to the global plastic pollution problem.

There’s no denying that plastics have become an integral part of the global economy. They are capable of delivering massive economic benefits thanks to their combination of low cost, versatility, durability and high strength-to-weight ratio.

As a key enabler for sectors such as packaging, construction, transportation, healthcare and electronics, plastics are without question one of the dominant materials of the modern world.

According to The Hartmann Report, the plastics business is the 8th largest industry in America, employing roughly a million people and generating just short of a half-trillion dollars annually.

Distribution of global plastic materials production by region in 2022. Source: Statista

Due to its low cost and weight, as well as barrier properties to keep food fresh, plastics have gradually replaced other packaging materials over the years. The WEF estimates that about 26% of plastics are used for packaging as of 2016, an increase from the 17% recorded in 2010.

“Plastic packaging volumes are expected to continue their strong growth, doubling within 15 years and more than quadrupling by 2050, to 318 million tonnes annually — more than the entire plastics industry today,” the WEF report said.

While plastic packaging is a primary driver of economic value, at the same time, the single-use nature of most plastics today poses questions about the long-term viability of the material.

Approximately 95% of plastic packaging material value or $80-120 billion annually is lost to the economy after a short first use. This is the case especially in business-to-consumer applications.

According to the WEF, an overwhelming 72% of plastic packaging is not recovered at all: 40% is landfilled, and 32% leaks out of the collection system — that is, either it is not collected, or it is collected but then illegally dumped or mismanaged.

Recycling fail

Despite the proliferation of curbside recycling programs, regional eco-centers, and an increasingly aware and motivated public, very little plastic is recycled, around 10% according to most estimates.

In the US, the recycling rate is even worse. According to a 2022 report by environmental groups Beyond Plastic and The Last Beach Cleanup, of the 40 million tons of plastic waste generated in the United States in 2021, only 5 to 6%, —or about 2 million tons, was recycled/ About 85% went to landfills, and 10% was incinerated. The rate of plastic recycling has decreased since 2018, when it was at 8.7%, per the study, via Smithsonian Magazine.

More than 40 years after the launch of the recycling symbol, only 14% of plastic packaging is collected for recycling. When additional value losses in sorting and reprocessing are factored in, only 5% of material value is actually retained for subsequent use.

Plastics that do get recycled are mostly processed into lower-value applications that are not again recyclable after use. The recycling rate for plastics in general is even lower than for plastic packaging, and both are far below the global recycling rates for paper (58%) and iron and steel (70-90%).

PET (polyethylene terephthalate) a type of clear, durable and versatile plastic which is used in beverage bottles, has a higher recycling rate than any other type of plastic, but even this is far from a success story. Globally, close to half of PET is still not collected for recycling, and a mere 7% is recycled bottle-to-bottle.

US EPA data shows that the recycling rate of PET was 26% in the United States in 2021, a slight decrease from the year before.

Lies

Apart from low plastic recycling rates, the other disturbing thing is how the public was sold a lie over recycling.

Since the 1970s, North Americans have been taught that most plastic is recyclable. The circular arrows symbol was invented by the plastics industry to indicate a product’s recyclability, however the secret they didn’t want us to know about, was that few plastics are actually recycled; the rest, such as mixed plastics (e.g. food wrappers, plastic film) are often landfilled or incinerated because it isn’t economical to recycle them.

In fact, it is often cheaper to make “virgin” plastic than to recycle it.

The CBC documentary ‘Plastic Wars’ describes how the plastics industry spent millions promoting recycling just to sell more plastic:

In the ’80s, the industry was at the centre of an environmental backlash. Fearing an outright ban on plastics, manufacturers looked for ways to get ahead of the problem. They looked at recycling as a way to improve the image of their product and started labeling plastics with the now ubiquitous chasing-arrows symbol with a number inside.

According to Ronald Liesemer, an industry veteran who was tasked with overseeing the new initiative, “Making recycling work was a way to keep their products in the marketplace.”

Most consumers might have assumed the symbol meant the product was recyclable. But according to experts in the film, there was no economically viable way to recycle most plastics, and they have ultimately ended up in a landfill. This included plastic films, bags and the wrapping around packaged goods, as well as containers like margarine tubs.

Effects on land

Ironically, plastic is a scourge of modern society because the material is virtually indestructible, a trait that made it appealing to consumers in the first place.

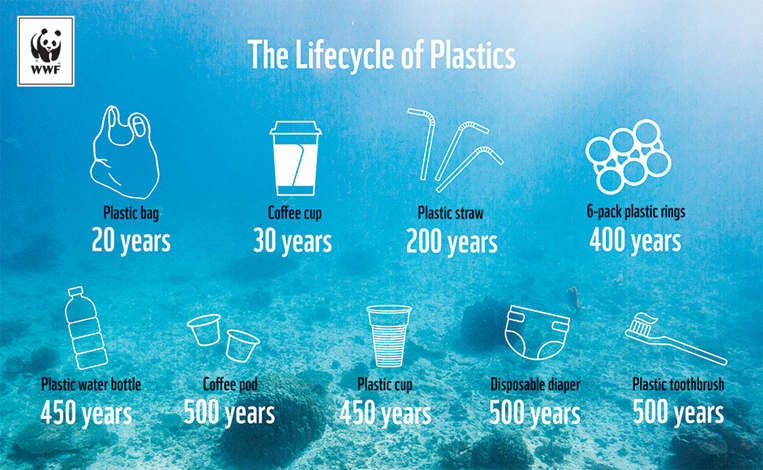

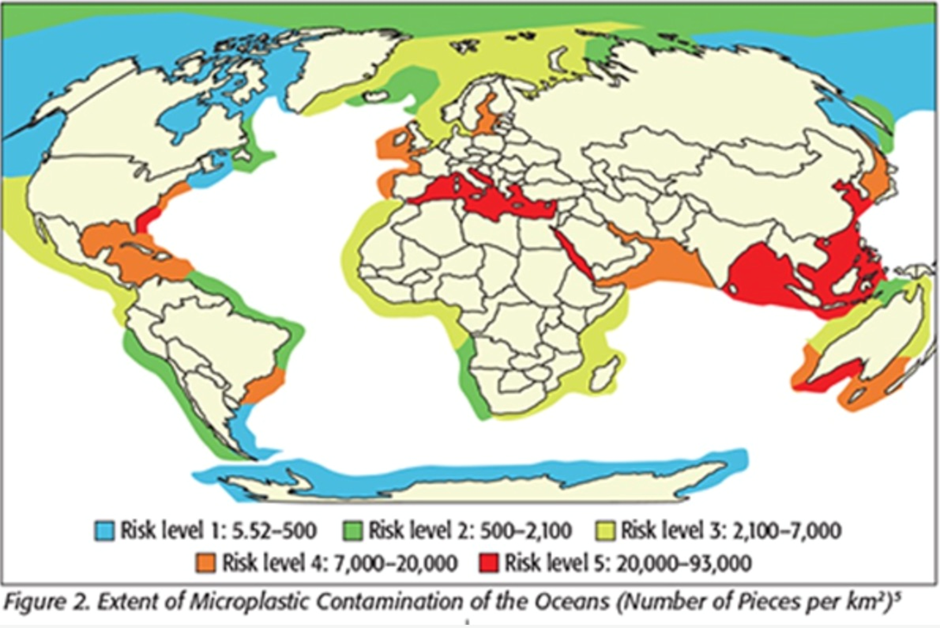

Most plastic products have long lifespans. Plastic bags, for example, can take up to 20 years to decompose, while takeaway coffee cups, despite being mostly paper, have a plastic lining that will endure for 30 years. Some items, like coffee pods, disposable diapers and plastic toothbrushes, could stay in landfills for five centuries!

If plastic were a country, it would be the fifth-highest pollution emitter in the world. That’s because 99% of plastic is made from fossil fuels. A significant portion of emissions comes from the extraction and transportation of fuels that create plastic, including methane from natural gas, considered 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Cracking plants that refine fuel and convert it to plastic are also extremely harmful to the environment. At the production stage, polyester, polyamide and acrylic, used in textiles, have the highest level of emissions.

Researchers quoted by The Guardian found that the black smoke from open waste plastic burning emits between 2% and 10% of the world’s carbon dioxide. The harmful practice also produces large amounts of dioxins and other pollutants that can persist in the food chain. In India, the extra chloride produced by burning plastics interacts with other pollutants, creating ground-level ozone that is estimated to reduce yields on some crops by 20-30%.

A part of Louisiana situated along the Mississippi River is often referred to as “Cancer Alley” because there are over 150 petrochemical facilities and refineries there. Air pollution in the area has been linked to higher levels of cancer in poor communities, CNBC wrote.

Carbon Tracker estimates that plastic production costs between $800 to $1,400 per ton, when the costs of CO2 emissions, air pollution, waste management and ocean cleanup efforts are included.

Only recently is science beginning to understand how plastic pollution is spread around the globe through intense storms. When Hurricane Larry struck the island province of Newfoundland, Canada, in 2021, university students set out to test whether small pieces of plastic called microplastics might be transported by hurricane winds. The results were astonishing.

A glass cylinder was placed on the Avalon peninsula of Newfoundland and the amount of plastics contained within it were measured before, during and after Hurricane Larry. The highest concentration was found during the hurricane, at more than 100,000 pieces per square meter per day — about five times the number of plastics found in the cylinder before and after the storm. It suggests that during hurricanes, the ocean whips microplastics up into the atmosphere and transports them by air.

Plastics in the food chain

For years it has been known that plastic breaks down into tiny particles that are consumed by shellfish, fish and mammals higher up the food chain, presenting a danger to human health if consumed.

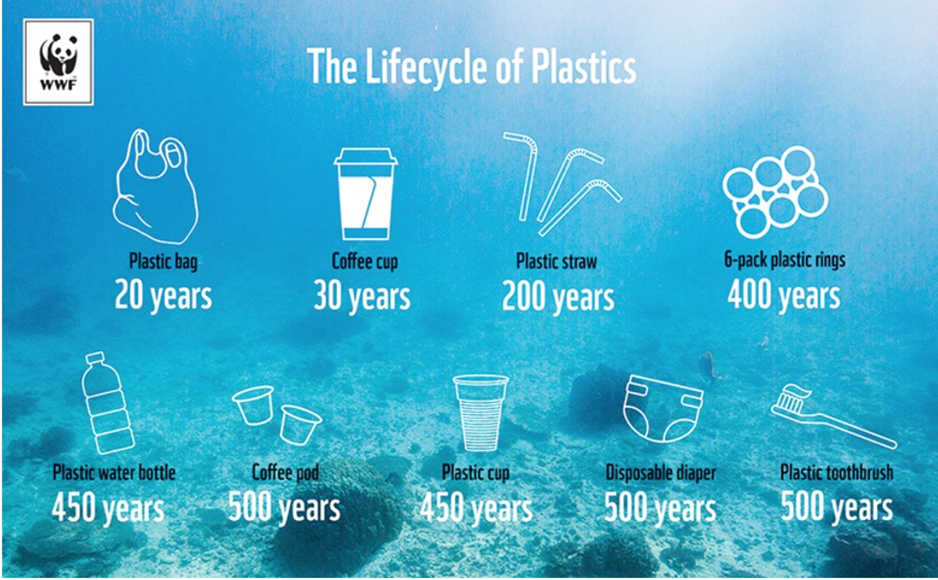

It is estimated there are over 150 million tonnes of plastic in the ocean. Around 8 million tonnes enter the seas every year — the equivalent of dumping a truckload of plastic garbage every minute.

National Geographic says the problem of discarded plastic is so severe, that if nothing is done, by 2050 the oceans will contain more plastic than fish, ton for ton.

It has become a much-discussed topic, and the subject of several documentaries, revolving around the harmful effects of minute plastic fragments, called microplastics and nanoplastics on plants, fish, sea birds, mammals, and eventually, humans at the top of the food chain.

Plastic that enters the ocean gets exposed to UV radiation, oxygen, high temperatures and microbial activity. Some plastics, those made from bacterial polymers, are naturally biodegradable. Others, such as take-away food containers, will only decompose when exposed to prolonged temperatures above 50 degrees C, conditions found in an industrial composter that cannot be replicated in the oceans.

Eventually the salt water, sun, wind and waves break the plastics down to tiny particles that are carried by ocean currents to even the most remote corners of the Earth.

What makes plastic so problematic? The answer comes down to chemistry. Plastic is a polymer molecule consisting of repeating identical units (homopolymer) or different sub-units in sequences (copolymer). Plastics are further categorized as thermoplastics, which soften when heated and can be molded; or thermosets, which cannot be molded or heated.

Both types cause pollution in a marine environment.

Plastics also contain chemicals to improve their properties, that cause harm when they enter the food chain.

Although hundreds of thousands of plastic materials have been invented, only six are extensively used: polyethylene terephthalate (PETE), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC-U), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS), or Styrofoam.

In the ocean, despite weathering that reduces plastics like water bottles and shopping bags to tiny particles, the original plastic polymer remains intact, unless it is converted into carbon dioxide, water, methane, hydrogen, ammonia and other inorganic compounds — a process that doesn’t happen in a marine environment.

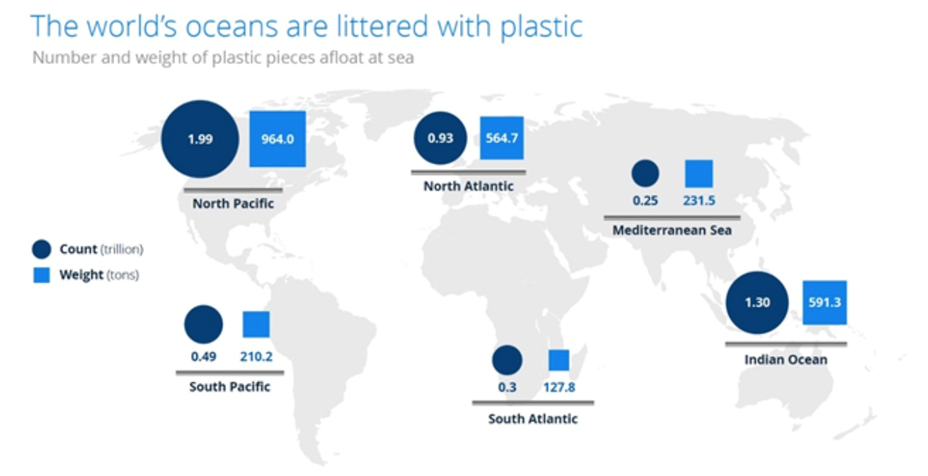

One of the surprising facts about microplastics is how entrenched they are in the global marine ecosystem. They have been detected in lakes and seas, in the sediments of rivers and deltas, and in the stomachs of the smallest and largest organisms, from zooplankton to whales. One study found that every square kilometer of the world’s oceans has 63,320 plastic particles floating on the surface.

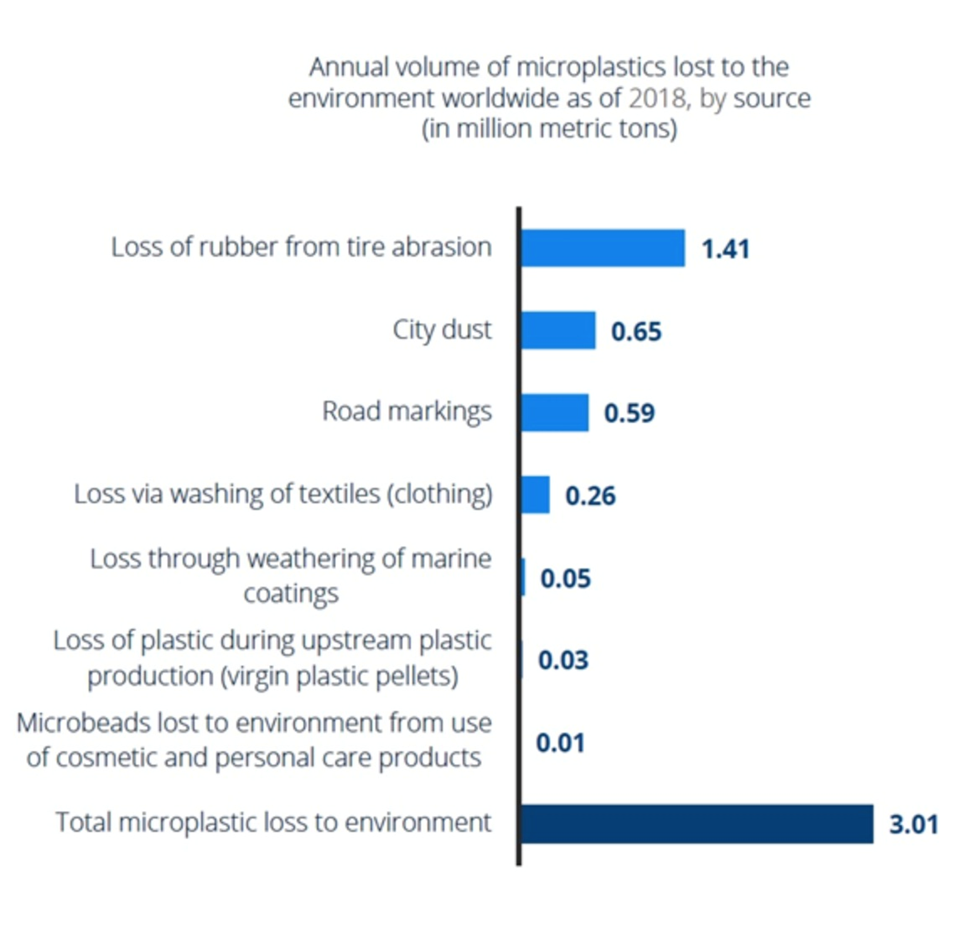

There are a number of ways that plastics get into the environment. Microbeads used as exfoliants in beauty products escape water filtration systems. Other primary sources include plastic powders in molding, and plastic nanoparticles in a variety of industrial processes.

The extensive and indiscriminate use of food packaging, car tires, paints, personal care products (e.g. toothpaste) and electronic equipment, are some more contributors to microplastic contamination.

Public awareness campaigns have mostly stopped the use of microbeads, but similar particles continue to be introduced into water systems.

One of the more surprising sources of microplastic pollution is fibers from synthetic fabrics. Plastic fibers from clothing, including polyester, acrylic and polyamides, are shed from garments when they are agitated in washing machines, then drained with the effluent water.

Experiments showed up to 1,900 microplastic fibers are released from just one synthetic garment in one wash.

Another less obvious source is the plastic debris from the mechanical abrasion of car tires on pavement. These tiny shards are carried by rain, snow melt and street cleaning into natural stormwater catch basins and municipal drainage systems.

Microplastics can also become part of the water cycle and delivered back to Earth as rain or snow.

Scientists think that tiny particles shed by anything plastic get incorporated into water droplets when it rains, then wash into lakes, rivers and oceans. When the water evaporates, the particles can end up in groundwater. They are then consumed by animals and people via drinking water and food, or breathed in. Microplastics can also attach to heavy metals or hazardous chemicals such as mercury, and adhere to particles from furniture and carpets containing toxic flame retardants, according to a microplastics researcher quoted by The Guardian.

The presence of microplastics in the marine food chain is well documented. As Food Safety explains,

Zooplankton, the microscopic sea organisms at the bottom of the food chain, is eaten by all kinds of fish. Fish ingest small pieces of plastic due to their continuous uptake of water. Microplastics get into the next level of the food chain when other animals eat fish contaminated with microplastics. Eventually, microplastics move all the way up to the top of the food chain.

There is even a scientific term for this process of animals that have eaten microplastics being eaten by other animals: trophic transfer.

A common way for nanoplastics to move up the food chain, is to be first consumed by algae, that is eaten by water fleas, which in turn become fish food.

One study looking for synthetic particles in sea turtles found microplastics in the guts of all 102 turtles that were examined. They have also been detected in quantities up to 273 particles per pound of sea salt, 300 fibers per pound of honey, and around 109 fragments per liter of beer.

Mussels and oysters harvested for eating reportedly had 0.36 to 0.47 particles per gram, meaning that shellfish consumers are ingesting up to 11,000 pieces of microplastic per year, according to Healthline.

A distinction must be made between microplastics and nanoplastics. The former are plastic fragments up to 5 millimeters, whereas the latter are between 0.001 and 0.1 micrometers (μm). Nanoplastics are so small, they are invisible to the naked eye or even under a simple microscope. They are even able to penetrate human cells walls, discussed further in the next section.

The problem is not only the nano/microplastics, but the pollutants they carry with them. When plastics move through the food chain, the attached toxins also move, and accumulate in animal fat and tissue through a process called bio-accumulation. Chemicals added to the plastic during the production process can leach from the plastic into the body of the animal that has eaten them. Read more here

Potential adverse effects, at high enough concentrations, may include immunotoxicological responses, reproductive disruption, anomalous embryonic development, endocrine disruption, and altered gene expression.

A laboratory study found fish that were fed nanoplastics, versus those that weren’t, showed abnormal behavior, such as slower eating and hyperactivity.

Among the marine and freshwater species known to ingest water contaminated with microplastics, are fish, bivalves and crustaceans. An animal can also be exposed to microplastics through its skin, or in the case of fish farms, eat plastic-contaminated fish meal.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, of 25 fish species of commercial significance, including Atlantic cod, 11 were found to contain microplastics.

When microplastics were fed to mice, they accumulated in the liver, kidneys and intestines, stressing these organs. Plastics also increased the level of a molecule that may be toxic to the brain, says Healthline.

In 2022, The Guardian said microplastic contamination was reported for the first time in beef and pork. In the pilot study, Dutch scientists found tiny plastic particles in 75% of meat and milk products tested, and in every blood sample. The study suggested microplastics were entering the stomachs of farm animals through the food they eat; plastic particles were identified in every sample of animal pellet food tested. Moreover, the food products themselves were wrapped in plastic.

Effects on human health

We’ll have to start recognizing a new food group, according to Reuters, every week people consume an amount of plastic the size of a credit card.

Microplastics are in our food.

In a limited study, Canadian researchers estimated the average person ingests over 74,000 plastic particles a year. Examining just a few food categories including fish, shellfish, sugar, alcohol, honey, bottled versus tap water, plus air, the study authors found the most microplastics in air, bottled water and seafood.

Chemicals associated with plastics are known to be harmful. The most well-studied is BPA — found in plastic packaging or food storage containers. When BPA leaks into food it can interfere with reproductive hormones in women.

But it gets worse. Recent evidence finds that plastic pollution is making us sick, demented, and in some cases, is literally killing us.

The presence of phthalates, used to make plastic flexible, in a petri dish was shown to increase the growth of breast cancer cells.

Last summer, a team of scientists at the University of Rhode Island published a study in the ‘International Journal of Molecular Science’. In the study, microplastics were fed to mice via drinking water at levels comparable to high levels of human exposure.

“They found that microplastic exposure induces both behavioral changes and alterations in immune markers in liver and brain tissues. The study mice began to move and behave peculiarly, exhibiting behaviors akin to dementia in humans. The results were even more profound in older animals.”

Also, “The researchers found that the particles had begun to bioaccumulate in every organ, including the brain, as well as in bodily waste.”

Cancer

There are two important points here. First is that nanoplastics are small enough to get inside our individual cells, and second is that they’ve been found in every organ every measured.

According to The Hartmann Report, there are studies showing they can contribute to, or cause everything from heart attacks and strokes to cancer and dementia. Of these, cancer is the one to worry about most.

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) has found the past few decades have seen an explosion of colorectal cancer among young people, it now being the leading cause of death among people under 50.

What is the connection to plastic? One study explained how the microplastics puncture and break down the mucosal lining of the gut and expose its cells directly to food and gastric juices, causing inflammation that in turn leads to cancer.

Another study posits the chemicals that make up the tiny plastic particles themselves — along with their ability to absorb other oil-based toxins — may also be contributing to the increase in colorectal cancers.

Over 10,000 different chemicals are used to make microplastics, with more than 2,400 identified as toxic or known disrupt endocrine or hormonal systems.

The tiny fragments are breathed in, eaten or consumed in liquids — most people get them all three ways.

As stated, microplastic ingestion has been linked to breast cancer, with a study in ‘Nature Briefing Cancer’ concluding that “chronic exposure to PPMPs [polypropylene microplastics] may increase the risk of cancer progression and metastasis.”

Just recently, a peer-reviewed study in ‘Toxicological Sciences’ journal found that all 62 tested placenta samples contained microplastics, with concentrations ranging from 6.5 to 790 micrograms per gram of tissue.

They have also been found in breast milk.

The most prevalent microplastic was polyethylene, which has been associated with several health conditions including asthma, hormone disruption impacting reproduction, and swelling or irritation of the skin. (The Epoch Times, March 7, 2024)

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and nylon each represented approximately 10% of the NMPs by weight, the article states. PVC has been linked to damage to the liver and reproductive system.

The piece goes on to say that the accumulation of microplastics in human tissue could explain the rise of (above-mentioned) colon cancer in people under 50, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Scariest of all, microplastics are known to affect fertility, and may play a role in the sharp drop in global male fertility over the past two decades.

Among the consumable items to avoid are bottled water, soft drinks and processed foods. One study found an average 325 nanoplastic particles per liter of bottled water, while another discovered an average 101 particles per liter of pop.

Most Americans eat about 15% of their diet as processed foods. A study looked at 3,600 processed food samples and found that annual microplastics consumption ranges from 39,000 to 52,000 particles, depending on age and sex.

People who only drink bottled water may be ingesting an additional 90,000 microplastics per year, compared to 4,000 for those who only drink tap water.

A recently published study found microplastics in almost all protein foods, including chicken, pork, seafood, beef, and plant-based meat alternatives.

Big Plastic

But get this. The big oil companies are concerned about loss of market share due to the energy shift, and are looking to petrochemicals, particularly plastics, as their next growth market.

According to the International Energy Agency, via CNBC, plastics made from fossil fuels are set to drive nearly half of oil demand growth by 2050, outpacing even hard-to-carbonize sectors like aviation and shipping. For example, producing a one-liter plastic bottle takes 250 milliliters of oil feedstock.

However, the CNBC article notes that plastics alone cannot save the fossil fuel industry, which is facing pressures from governments wanting to reduce or ban single-use plastics, and implement producer-responsibility schemes to cover waste management and cleanup costs.

Moreover, plastics are a much smaller segment than oil and gas, with petrochemicals comprising just 13% of ExxonMobil’s revenue in 2020, and 6.5% of Shell’s 2020 revenue, states CNBC.

Legislative attempts and failures

Around a year ago, the Canadian government was in court defending its ban in single-use plastics that went into effect in December 2022.

The complainant, a trifecta of large plastic manufacturers — Dow Chemical Canada, Imperial Oil and Nova Chemicals — accused the government of introducing a plan with “fatal flaws”. Their two main arguments were, 1/ it is not the federal government’s place to regulate plastic pollution when the provinces and territories typically handle waste management; and 2/ the government failed to demonstrate it had enough scientific evidence to justify the ban.

The Liberal government commissioned a scientific assessment of plastic pollution in 2020. It found that plastic pollutes rivers, lakes and other water bodies, harming wildlife and leaving microplastic fragments in drinking water.

That report was followed by the federal government announcing dates for a ban on the manufacture, sale and import of certain plastic products. Some of these prohibitions have already taken effect and some won’t happen until 2025. (CBC News, March 7, 2023)

According to federal data, in 2019 15.5 billion plastic grocery bags, 4.5 billion pieces of plastic cutlery, three billion stir sticks, 5.8 billion straws, 183 million six-pack rings and 805 million takeout containers were sold in Canada. Only a tenth of the plastic Canadians use is recycled, resulting in 3.3 million tonnes sent to landfills annually, almost half of it plastic packaging.

The court case decided in November 2023 was a loss for the Canadian government. The Federal Court overturned Canada’s ban on single-use plastic, deeming it “unreasonable and unconstitutional”.

As stated by Global News, The decision found that the classification of plastics in the cabinet order was too broad to be listed on the List of Toxic Substances in Schedule 1 and the government acted outside of its authority.

“There is no reasonable apprehension that all listed Plastic Manufactured Items are harmful,” the decision read.

The decision has essentially quashed a cabinet order that listed plastic manufactured items, such as plastic bags, straws, and takeout containers, as toxic under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act.

The upshot? The government is only able to regulate substances for environmental protection if they are listed as toxic under CEPA.

South of the border, single-use plastic bans are being similarly challenged. According to The Hartmann Report, About a dozen Republican-controlled states have passed ALEC- and industry-recommended laws banning the regulation of plastic items, including products that shed micro- and/or nanoplastics…

Now, no city in Arizona — nor in about a dozen other states — can ban plastic bags or other things that contribute to microplastics in their environment.

Outside of Obama’s 2015 ban on the intentional insertion of microplastics in cosmetics, foods, and toothpaste, there are currently no federal standards that regulate microplastics, in large part because of the pressure from and power of the industry’s lobbyists. The only state to even require microplastics testing for drinking water is California, with a new law that went into effect in September [of 2022].

In contrast to North America, legislative attempts in Europe have been more successful. The EU Directive on Single-Use Plastics mandates that by 2025, all beverage bottles made of PET plastic must contain at least 25% recycled content, bans a wide variety of single-use products, and implements an extended producer responsibility scheme that makes plastics producers cover the cost of waste management and cleanup.

Also on the positive side, the CNBC article notes Maine and Oregon recently introduced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) laws that make plastics producers pay for recycling programs. More than 70 companies have called for a global pact to cut plastics production and decouple it from fossil fuels. Signatories include AMCOR — a large plastic packaging manufacturer, Unilever, Walmart, Pepsi and Coke.

March 1, 2022 was the date on which nearly the entire world agreed on the planet’s first global treaty to tackle plastic pollution.

At a meeting of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) in Nairobi, Kenya, as many as 175 countries passed a resolution on the world’s first treaty to end the “plastic crisis”, which has gotten worse each year following the plastic age of the 1950s.

Many described it as the most significant environmental deal since the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Some even called it the world’s most ambitious environmental action of the 21st century, comparing it to the 1989 Montreal Protocol that phased out ozone-depleting substances.

However a year and a half later, at the third meeting of the UN’s Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution (INC-3) also in Nairobi, the goal of the Nov. 13-19 2023 convention did not come any closer to ending plastic pollution.

According to The Plastic Soup Foundation, Differences of opinion flared up over how much, and even if, plastic production should be reduced… Indeed, plastic-producing (oil) countries and industries claim that production has nothing to do with pollution.

The next meeting is in April this year in Ottawa, Ontario. Negotiators plan to reach consensus by the end of 2024 at INC-5, slated to take place this November in Seoul, South Korea.

However, as early as 2018, the plastics lobby started a strong lobby campaign to fight against proposed European Union regulations, including a tax on virgin plastics that would make production of new plastic more expensive and make it cheaper to use recycled plastic.

At last November’s INC-3 conference in Nairobi, corporations with representatives at the negotiating session reportedly spent more than $85 million on lobbying and political contributions in the 2022 election US election cycle.

Registered delegates at INC-3 include representatives from several major U.S. companies with interests in plastic, such as ExxonMobil, Chevron, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Dow, Inc. Trade groups representing hundreds more companies are also in attendance, including the American Chemistry Council, the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers, and the International Council of Beverage Associations…

The American Chemistry Council, a trade group representing hundreds of companies, tops the list of 2022 U.S. lobbying expenditures with $19,820,000…

An analysis of industry representation at INC-3 from the Center for International Environmental Law found that the 143 corporate lobbyists attending outnumber the combined delegations from 70 countries, and far surpass the 38 scientists attending as part of a scientists’ coalition.

Conclusion

Plastic is a scourge of modern society.

Plastics have become so ubiquitous – in un-recycled plastic bags, packaging of all shapes and sizes, single-use straws and utensils, coffee pods, plastic microbeads, etc. – that they have literally become part of us. Only 10% of plastic containers are recycled. The rest ends up in landfills, rivers, lakes and finally, the ocean.

Tiny particles shed from thousands, maybe millions of plastic items are getting into the soil, the water, the air and the food chain.

We are now eating, breathing and drinking plastic. Recent research shows that microplastics cause cancer and that they may even have an impact on fertility.

We need to figure out a way to get plastic out of our water and food. What’s the solution?

Part of it lies in more government regulation on the plastics industry and better consumer recycling protocols. The latter will help to reduce the amount of plastic that is land-filled.

But most experts believe that recycling is not enough, and that production of plastics needs to be significantly curtailed to solve the plastic pollution crisis. That requires a change in behavior to use less plastic (not easy). Another more exciting option, in step with increasingly stringent government regulations on single-use plastic, is the introduction of alternative products to plastic that degrade more easily in a compostable environment. More on that in our next article.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.