Our plastic world

2022.01.20

Think about this: Every time you buy a soft drink that comes with a plastic straw, and toss it into the garbage, you are contributing to the global plastic pollution problem.

The same goes for hundreds, maybe thousands of other single-use plastics, including ubiquitous food packaging, take-out containers & cutlery, coffee cups with plastic lids, water bottles, shopping bags, and throw-away plastic covers like those used by drycleaners and auto-service departments.

Originating more than 150 years ago as a substitute for billiard balls made of ivory, plastic is both a wonder-material that has aided in the progression of modern industry and life (plastic production grew 300% during World War Two, used for example in parachutes, helmet liners and bazooka barrels; endless plastic products have been designed to make life easier, it being cheap, sanitary, lightweight, moldable and safe), and a scourge, due to the inability of science to come up with a solution to the seemingly intractable issue of plastic waste.

Plastic has been filling up our landfills for decades, or incinerated, thus contributing to land/ ocean/ air pollution, and carbon emissions. Researchers quoted by The Guardian found that the black smoke from open waste burning emits between 2% and 10% of the world’s carbon dioxide. The harmful practice also produces large amounts of dioxins and other pollutants that can persist in the food chain. In India, the extra chloride produced by burning plastics interacts with other pollutants, creating ground-level ozone that is estimated to reduce yields on some crops by 20-30%.

If plastic were a country, it would be the fifth-highest emitter in the world. That’s because 99% of plastic is made from fossil fuels. A significant portion of emissions comes from the extraction and transportation of fuels that create plastic, including methane from natural gas, considered 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Cracking Plants that refine fuel and convert it to plastic are also extremely harmful to the environment. At the production stage, polyester, polyamide and acrylic, used in textiles, have the highest level of emissions.

Over the years, plastic has followed a hockey stick-shaped growth trajectory. We make 190 times more plastic than we did in 1950; in 2017, the United States alone produced 35 million tons, out of a global total of about 400 million tons.

Despite the proliferation of curbside recycling programs, regional eco-centers, and an increasingly aware and motivated public, very little plastic is recycled, around 10% according to most estimates. Another 12% is incinerated, reducing it to ash, gas and heat. The other 79% makes its way to a landfill or escapes into the environment.

Between 1950 and 2015, an estimated 6.3 billion metric tons ended up as waste — the equivalent mass of 42 million blue whales, each weighing 150 tonnes. (1 metric ton = 1.10231 US tons)

Plastic packaging in 2015 represented the highest waste category, @ 141 million tons, followed by textiles at 42 million tons, and consumer/ institutional products at 37Mt.

Our plastic world

It is estimated there are over 150 million tonnes of plastic in the ocean. Around 8 million tonnes enter the seas every year — the equivalent of dumping a truckload of plastic garbage every minute.

On land, plastic pollution has been with us since the material was invented in 1907.

The expected decline in oil production due to vehicle electrification and the switch to renewables, is unlikely to affect plastics, which are a by-product of crude oil. According to a Statista report, plastics production is forecast to become the largest driver of oil demand growth in the coming years, exceeding the oil demanded by global road transportation by 2050. A one-liter plastic bottle takes 250 milliliters of oil feedstock to be produced.

National Geographic says the problem of discarded plastic is so severe, that if nothing is done, by 2050 the oceans will contain more plastic than fish, ton for ton.

It has become a much-discussed topic, and the subject of several documentaries, revolving around the harmful effects of minute plastic fragments, called microplastics and nanoplastics on plants, fish, sea birds, mammals, and eventually, humans at the top of the food chain.

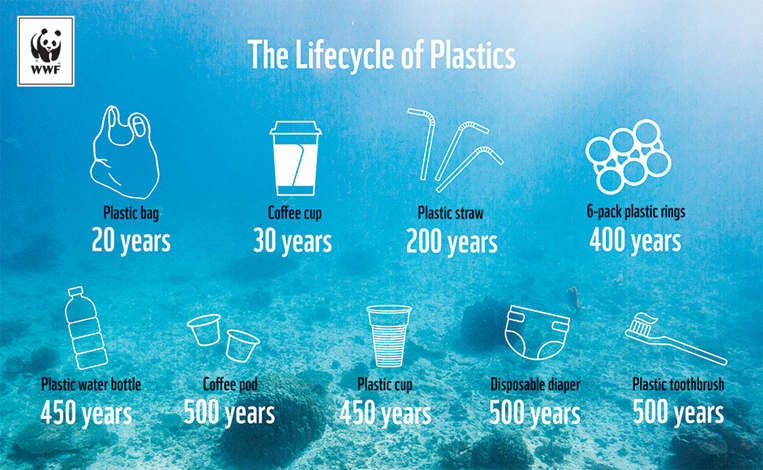

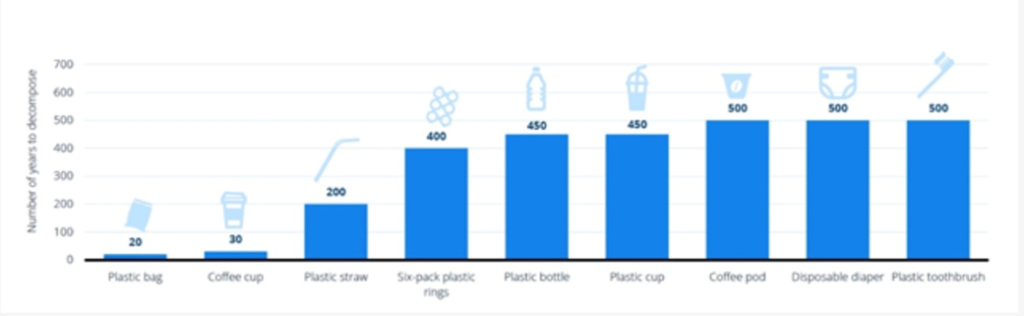

The problem stems from the fact that plastic is virtually indestructible. A trait that was once sold to consumers as a virtue, has become a vice, due to the ubiquity of plastic especially in the marine environment.

Most plastic has a very long lifespan. Plastic bags, for example, can take up to 20 years to decompose, while takeaway coffee cups, despite being mostly paper, have a plastic lining that will endure for 30 years.

Other items, including coffee pods, disposable diapers, and plastic toothbrushes, will be in landfills for five centuries!

Plastic that enters the ocean gets exposed to UV radiation, oxygen, high temperatures and microbial activity. Some plastics, those made from bacterial polymers, are naturally biodegradable. Others, such as take-away food containers, will only decompose when exposed to prolonged temperatures above 50 degrees C, conditions found in an industrial composter that cannot be replicated in the oceans.

Eventually the salt water, sun, wind and waves break the plastics down to tiny particles that are carried by ocean currents to even the most remote corners of the Earth.

Some marine animals get entangled in plastic fishing nets or are impaled by plastic straws. Others mistake the colorful plastic fragments for food and eat them. However since they cannot be digested, the pieces create a feeling of artificial satiation in the animals that can lead to starvation.

Humans are ingesting plastics as well. According to Statista, every week people consume an amount of plastic the size of a credit card.

What makes plastic so problematic? The answer comes down to chemistry. Plastic is a polymer molecule consisting of repeating identical units (homopolymer) or different sub-units in sequences (copolymer). Plastics are further categorized as thermoplastics, which soften when heated and can be molded; or thermosets, which cannot be molded or heated.

Both types cause pollution in a marine environment.

Plastics also contain chemicals to improve their properties, that cause harm when they enter the food chain.

Although hundreds of thousands of plastic materials have been invented, only six are extensively used: polyethylene terephthalate (PETE), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC-U), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS), or Styrofoam.

In the ocean, despite weathering that reduces plastics like water bottles and shopping bags to tiny particles, the original plastic polymer remains intact, unless it is converted into carbon dioxide, water, methane, hydrogen, ammonia and other inorganic compounds — a process that doesn’t happen in a marine environment.

Especially worrying are “nanoplastics” — pieces that are so tiny, they are able to penetrate human cell walls.

A distinction must be made between microplastics and nanoplastics. The former are plastic fragments up to 5 millimeters, whereas the latter are between 0.001 and 0.1 micrometers (μm). Nanoplastics are so small, they are invisible to the naked eye or even under a simple microscope.

One of the surprising facts about microplastics is how entrenched they are in the global ecosystem. They have been detected in lakes and seas, in the sediments of rivers and deltas, and in the stomachs of the smallest and largest organisms, from zooplankton to whales. One study found that every square kilometer of the world’s oceans has 63,320 plastic particles floating on the surface.

According to Food Safety magazine, microplastics are present in various food products, including seafood, as well as in bottled water. In addition, microplastics can also help introduce other contaminants to foods. Persistent organic pollutants and other toxins in water can also be attracted to these particles. Once consumed by plankton, these contaminants are passed through the food chain to small fish and eventually to humans. While their impact on human health is currently debated, high volumes of microplastics in rats have been found to cause cancer.

There are a number of ways that plastics get into the environment. Microbeads used as exfoliants in beauty products escape water filtration systems. Other primary sources include plastic powders in molding, and plastic nanoparticles in a variety of industrial processes.

The extensive and indiscriminate use of food packaging, car tires, paints, personal care products (eg. toothpaste) and electronic equipment, are some more contributors to microplastic contamination.

Microplastics can also become part of the water cycle and delivered back to Earth as rain or snow.

Scientists think that tiny particles shed by anything plastic get incorporated into water droplets when it rains, then wash into lakes, rivers and oceans. When the water evaporates, the particles can end up in groundwater. They are then consumed by animals and people via drinking water and food, or breathed in.

If nano-scale plastic has become prevalent in drinking water, oceans, rainwater, and the animals that mistakenly eat them, it’s not a stretch to say that microplastics are probably in our food.

One study looking for synthetic particles in sea turtles found microplastics in the guts of all 102 turtles that were examined. They have also been detected in quantities up to 273 particles per pound of sea salt, 300 fibers per pound of honey, and around 109 fragments per liter of beer.

Mussels and oysters harvested for eating reportedly had 0.36 to 0.47 particles per gram, meaning that shellfish consumers are ingesting up to 11,000 pieces of microplastic per year, according to Healthline.

A common way for nanoplastics to move up the food chain, is to be first consumed by algae, that is eaten by water fleas, which in turn become fish food.

The problem is not only the nano/microplastics, but the pollutants they carry with them. When plastics move through the food chain, the attached toxins also move, and accumulate in animal fat and tissue through a process called bio-accumulation. Chemicals added to the plastic during the production process can leach from the plastic into the body of the animal that has eaten them. Read more here

Potential adverse effects, at high enough concentrations, may include immunotoxicological responses, reproductive disruption, anomalous embryonic development, endocrine disruption, and altered gene expression.

While microplastics’ effects on human health have not been widely studied, it’s safe to say that inhaling or ingesting them should be avoided. This may be extremely difficult however; one study found plastic fibers in 87% of the human lungs studied.

Chemicals associated with plastics are known to be harmful. The most well-studied is BPA — found in plastic packaging or food storage containers. When BPA leaks into food it can interfere with reproductive hormones in women.

Another chemical, phthalates es, is used to make plastic flexible. The presence of phthalates in a petri dish was shown to increase the growth of breast cancer cells.

In a limited study, Canadian researchers estimated the average person ingests over 74,000 plastic particles a year. Examining just a few food categories including fish, shellfish, sugar, alcohol, honey, bottled versus tap water, plus air, the study authors found the most microplastics in air, bottled water and seafood.

Single-use plastic bans

Thankfully, the news on plastic pollution isn’t altogether bleak. While the pandemic has caused many countries to hit “pause” on their plastic recycling, re-use and reduction programs, in recent years some positive developments have taken place.

Several US jurisdictions have enacted policies on plastic pollution. In 2018 Seattle became the first US city to slap a ban on plastic straws and single-use plastic utensils. Eight states — California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, New York, Oregon, and Vermont — have banned single-use plastic bags.

Montreal banned plastic bags thinner than 50 microns in 2018, followed by bans on plastic bags and straws in the Vancouver Island communities of Victoria, Tofino and Uclulet in 2019. On the other side of the country, PEI’s Plastic Bag Reduction Act came into effect on July 1, 2019.

According to CTV News, the Canadian government’s planned ban on six single-use plastic items — shopping bags, cutlery, straws, stirs sticks, food take-out containers and six-pack rings — has been delayed to 2022.

In step with increasingly stringent government regulations on single-use plastic, the manufacturing sector has been busy developing technologies that can serve as alternatives to plastic, while maintaining many of its same characteristics.

“ESG-friendly” (environmental, social and governance is the buzzword of the day Alternatives to single-use plastic is an idea whose time has come.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.