Global warming catastrophe is just getting started – Richard Mills

2024.10.09

Florida was bracing for the second of two back-to-back hurricanes Monday, with Hurricane Milton bearing down on the state after a devastating Hurricane Helene made landfall on Sept. 26.

Milton is classified as Category 5, the strongest on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale. It went from a Category 2 to Category 5 in just a few hours, said Al Jazeera, with a reported maximum wind speed of 280 kilometers an hour.

The death toll from Hurricane Helene is still being counted; it was 227 as of Saturday, with a trail of destruction left across six states: North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Tennessee and Virginia.

Helene was classified as Category 4, with maximum wind speeds of about 225 km/h.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis warned on Sunday that storm surges caused by Milton could exceed those caused by Helene, adding that the hurricane could also cause bigger power outages than Helene, which cut off electricity to over 2 million residents.

It’s often said that global warming is making hurricanes worse. This is the first time the Atlantic Ocean is experiencing three hurricanes at once. Along with Milton, Category 1 Hurricanes Kirk and Leslie are also churning offshore.

Other notable hurricane facts as reported by Al Jazeera:

- Milton’s maximum winds are the strongest for a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico this late in the calendar year on record. The latest previous record was Hurricane Rita in September 2005.

- Since 1979, only three hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico have matched the intensity of Milton’s current low pressure reading: Allen in 1980, Katrina and Rita in 2005.

- With a warming climate, storm surges, rainfall and winds associated with hurricanes are becoming more destructive, according to the US-based nonprofit advocacy group Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

- It attributes this to rising sea levels and warmer oceans, which cause intense evaporation and the transfer of heat from oceans to the air. According to the EDF, the proportion of major hurricanes in the Atlantic has doubled since 1980.

West Coast atmospheric river

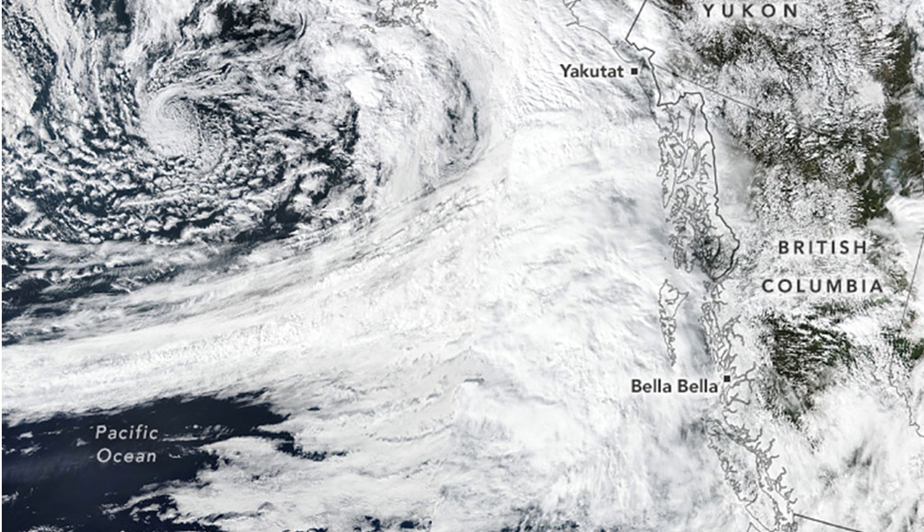

Meanwhile, on the Pacific Coast of North America, parts of the US and much of Canada experienced a particularly wet September. Researchers quoted by The Inertia suspect it was because an “atmospheric river” was one of the world’s most intense in decades. These bands of moisture in the sky first entered the lexicon in 2021, during the Pacific Northwest Floods, including the especially hard-hit Fraser Valley of southwestern British Columbia.

The storm made landfall near Bella Bella as a Category 5 atmospheric river, dumping rain on the Coast and Hazelton mountains and Glacier Bay National Park — elevating the risk of floods. The reason for the river likely had to do with a change in the Arctic Oscillation Pattern, referring to an atmospheric circulation pattern over the mid-to-high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

Warming oceans

Warm ocean water holds the key to the most powerful storms nature can throw our way, according to The Weather Network.

Back in 2005, Hurricane Katrina first moved across southern Florida on Aug. 25, traversing swampy terrain. Its intensity skyrocketed once it encountered the bathtub-like waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Over the next two days Katrina grew into a Category 5 Hurricane as it swirled toward the northern Gulf Coast.

The hot water that Katrina traversed in the eastern Gulf of Mexico was the key to its sudden and devastating intensification, and it was a classic example of why meteorologists get nervous whenever a storm is about to encounter seas warm enough to bathe in.

The Weather Network notes that tropical cyclones grow from a depression to a storm, then into a full-blown hurricane as thunderstorms gather strength around the centre of low pressure.

The thunderstorms intensify when they pass over warmer waters and weaken when they encounter cooler waters.

In late June and early July of this year, the sea surface temperatures over which Hurricane Beryl rapidly intensified was about 1.8 degrees Celsius warmer than normal based on the 1991-2020 average. PreventionWeb states:

As ocean temperatures warm in response to climate change, they provide unnatural extra fuel for tropical cyclones to intensify, and increase the likelihood that storms will undergo rapid intensification — increasing maximum sustained winds by at least 30 kt (about 35 mph) in a 24-hour period.

El Ninos will become more common

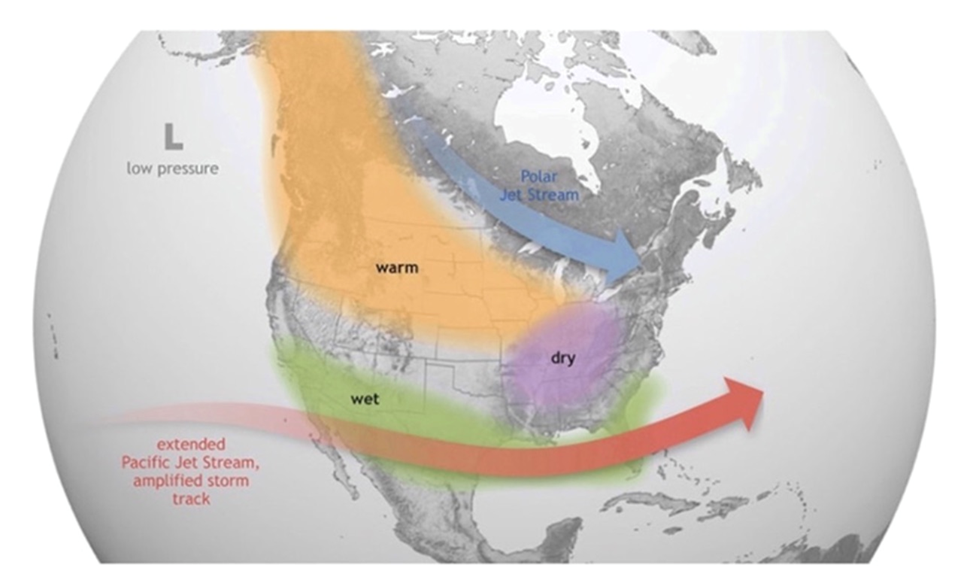

It’s been well-established that warmer, or colder-than-average ocean temperatures have an influence on weather. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), El Nino causes the Pacific jet stream to move south and spread further east. During winter, this leads to wetter conditions than usual in the southern US and warmer and drier conditions in the north.

October 2023 hit a world heat record. According to EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), October’s previous 2019 record was broken by 0.4C, “which is a huge margin,” said C3S Deputy Director Samantha Burgess.

Last year’s average temperature was about 1.4C higher than the pre-industrial era; early estimates suggest 2024 will be between 1.3 and 1.6 degrees higher.

Bloomberg notes that almost every month in 2023 was warmer than the 1991-2020 average. After El Nino started, monthly heat records were shattered in June, July, August, September, October and November. Last July was the warmest month ever observed and July 6 was the hottest day on record.

How common will El Nino events become in future?

Scientists at the University of Arizona compiled a record of El Nino’s variability in the Pacific Ocean 21,000 years ago during the last glacial maximum, when the climate was much cooler than today. This record was largely based on measurements of shells grown by microscopic plankton called foraminifera.

The shells provided a record of the temperatures at the sea surface, where the plankton grow. When the tiny organisms die, they sink to the depths, where their shells are preserved in the sediment accumulating on the seafloor.

A reconstruction of Pacific Ocean temperatures 21,000 years ago, based on the chemistry of tiny shells, adds hefty support to projections that climate change will make strong El Niño events far more common, leading to more extreme weather around the world.

“We’re projecting a pretty dramatic change,” says Kaustubh Thirumalai at the University of Arizona.

According to their analysis, as global temperatures rise, a layer of warm water at the ocean’s surface becomes thinner, making it easier for winds and currents to spur an extreme El Nino event.

Under a medium emissions scenario, the model projects an extreme El Nino event could occur every decade this century rather than the once every two decades pattern seen historically.

“We could be left with this type of climate with a massively active El Niño,” says Pedro DiNezio at the University of Colorado Boulder, a co-author of the study.

Slowing AMOC and disappearing sea ice

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a large system of water currents that circulates water from south to north and back, in a long cycle within the Atlantic Ocean.

This system of deep-water circulation, sometimes referred to as the Great Ocean Conveyor Belt, sends warm water from the Gulf of Mexico to the

North Atlantic, where it releases heat to the atmosphere and warms Western Europe. The cooler water then sinks to great depths and travels all the way to Antarctica and eventually circulates back up via the Gulf Stream (see below).

Without climatic disruptions, the currents move water around the globe, along with nutrients key to the survival of marine species.

But climate scientists have been raising concerns that rising temperatures are throwing a wrench into the conveyor belt-like currents system. Sensors stationed along the North Atlantic show that the volume of water moving northward has been sluggish, potentially affecting sea levels and weather. If the AMOC were to stop altogether, it could bring extreme climate change within decades, not centuries or millenia — a period so short it wouldn’t even register in geologic time.

New research reveals this key cog in the global ocean circulation system is currently at its weakest point in over a thousand years, and is being further weakened due to the rise in global temperatures.

The problem is that warming seas and melting sea ice are hindering the sinking of these great water masses.

“The huge amounts of melting ice are pouring an incredible amount of fresh water into the North Atlantic,” says Sandro Carniel, a climatologist and oceanographer at the National Research Center. “Less and less salty and warmer waters are helping to lag the general circulation of currents.”

So, is the AMOC likely to come to a halt? If so, when, and what would be the effects?

According to the paper, the AMOC is getting closer and closer to collapse, with the tipping point likely arriving before the end of this century. This is the “point of no return” when we rapidly accelerate towards global heating.

AMOC collapse — a coming climate catastrophe — Richard Mills

Shutdown of deep ocean current could cause extreme climate change as soon as 2025 — Richard Mills

It was recently reported that Arctic sea ice had retreated to near-record lows in the Northern Hemisphere. According to researchers at NASA and the National Snow and Ice Data Center, via earth.com, the ice shrank to a minimal extent of about 4.28 million square kilometers.

While that sounds like a lot, it’s ~1.94 million square km below the 1981 to 2010 end-of-summer average of 6.22 million square km — an area larger than the state of Alaska.

2024’s minimal extent wasn’t as low as the record set in 2012, but the trend since the 1970s has been downwards. According to NSIDC, the Arctic has been losing about 77,700 square km of sea ice per year.

It’s also getting younger, with the majority of ice in the Arctic Ocean thinner, first-year ice which is less able to survive the warmer months.

(Curiously, however, this winter’s layer Arctic sea ice is forming sooner than normal. One source reports the summer shipping window on Russia’s Northern Sea Route is closing weeks ahead of schedule. Unlike the last couple of summers, residual winter ice in the eastern section of the route has resulted in early ice formation, especially in the Laptev, East Siberian and Chucki seas.)

Ice surrounding the continent of Antarctica is also diminishing. Scientists think the ice is on track to be just 16.96 million km compared to the average maximum extent of 18.71 million square km between 1981 and 2010.

New Scientist (paywall) reports an area of missing Antarctic sea ice twice the size of Texas is adding to concerns that the ice has seen a lasting “regime shift”.

The publication notes Antarctic sea ice has reached near-record lows for the second year in a row, adding that researchers were shocked when they found the sea ice encircling the continent in early 2023 smashed the record low set in 2022.

Following a spike in 2014, the ice growth has declined dramatically, with the recurring loss hinting at warmer temperatures in the Southern Ocean. This is a feedback loop we are familiar with.

Scientists have found that the Arctic is heating up four times faster than the rest of the world. Much of this has to do with the phenomenon known as “Arctic amplification”, or the loss of sea ice.

The Arctic Ocean is mostly covered with a layer of sparkling sea ice. But as the planet warms, the sea ice begins to dissipate and exposes more of the ocean’s surface warming the water, the loss of ice allows more heat to escape from the warmer water into the colder atmosphere. And as more ice vanishes from the sea, Arctic temperatures rise faster, which in turn makes the sea ice vulnerable to further melting.

The same thing is happening in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica, which is warming about twice as fast as the global average.

Researchers at the UK’s University of Exeter wanted to know how much of Antarctica is “turning green” due to record-high temperatures and record-low levels of sea ice surrounding the continent.

Using 35 years of satellite photography taken over the 522,000 square km Antarctic Peninsula, Tom Roland and his colleagues found In 1986, less than 1 km² of the Antarctic Peninsula was covered in vegetation, but by 2021 this had increased to nearly 12 km².

Between 2016 and 2021, the rate at which this vegetation was expanding increased by more than 30 per cent.

The risk of increased vegetation, including mosses, lichens, liverworts and fungi, is that it will lead to increased soil formation, which raises the risk of colonization by non-native/ invasive species.

Polar vortex weakening, shifting to the poles

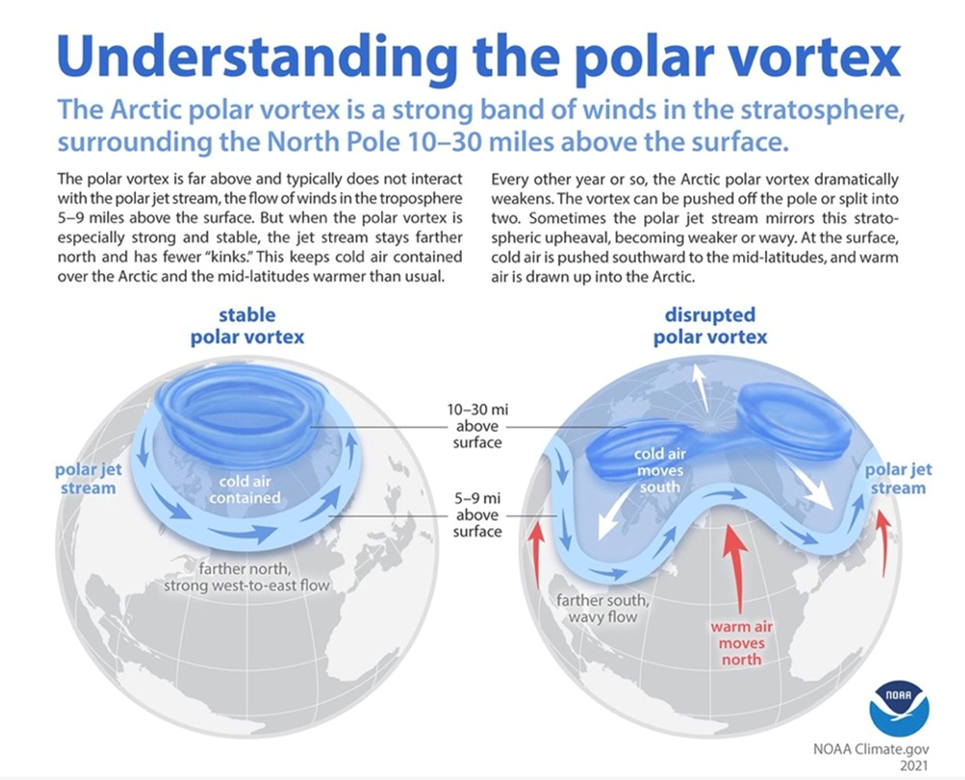

The polar vortex is a seasonal atmospheric phenomenon whereby high winds swirl around an extremely cold pocket of Arctic or Antarctic air.

The winds are like a barrier that contains the cold air, but when the vortex weakens, the cold air “escapes” from the vortex and travels south, bringing with it a cold blast of Arctic weather. If the polar vortices collapse, it would mean a total disruption of normal atmospheric warming and cooling. Without halos of swirling Arctic and Antarctic winds serving to cool the poles, they would be left to heat up, accelerating global warming.

It was recently reported that sections of the planet’s jet streams — bands of fast-moving air that blow east to west — are shifting towards the poles, which could cause dramatic changes in weather from the western United States to the Mediterranean.

The shifts have occurred over decades and are likely a response to global warming, states an article in New Scientist. It explains that Climate models have long anticipated that global warming would cause the position of the jet streams in each hemisphere to shift towards their respective poles. This is expected to occur as increasing heat in the tropics pushes the storms that add fuel to the jet streams further from the equator.

The problem has been the length of study; records only started being taken in 1980 and only recently became long enough to detect a pattern.

Thomas Keel and colleagues at University College London found the average position of the North Pacific Jet Stream between December and February has seen a northward shift of about 30-80 kilometers per decade. The researchers project the shift will continue in coming decades under a high-emissions scenario.

Another study at Oxford University found that, when jet streams across both hemispheres were analyzed, the showed a clear poleward shift between 1979 and 2019. The trend was clearest above the Southern Ocean.

Why is this significant? Because the shifts influence weather patterns:

Shifts in the position of the jet streams have an effect on global weather because they steer and create weather systems, says Jennifer Francis at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts. For instance, she says a shift in the North Pacific Jet Stream could exacerbate heat and drought in the western US by redirecting storms.

Other regions that are influenced by jet streams, such as the Mediterranean, Chile, South Africa and Australia, could be affected by similar shifts, says Woolings. “If you’re right on the edge of the region that gets rainfall due to the jet stream, even a degree shift of latitude could be really serious.”

A related question, says New Scientist, is whether the temperature changes driving the shifts have make the jet streams “wavier”, leading to extreme cold and extreme heat events.

The blast of cold weather that hit North America in January 2019 exemplifies this polar vortex breakdown. The Arctic polar jet stream meandered southward, bringing freezing-cold weather to the US Midwest, which saw windchills of -50F, along with fatalities and problems with the power grid in other parts of the country.

A wandering polar jet stream can also cause extreme heat, such as the “heat dome” experienced by Western North America in the summer of 2021, that killed 619 people in British Columbia alone.

There is recent evidence of a an unusually weak polar vortex developing in the stratosphere above the North Pole. The phenomenon is connected to how weather patterns will develop over the US and Canada this month, and could even alter them during this winter.

According to Severe Weather Europe, the polar vortex is the weakest it’s been in early October in the past 40 years. The reason, naturally, we haven’t seen colder air escaping from the swirling vortex and reaching down to southern climes is because it’s too early in the season. If the same situation occurred in December or January, it would likely lead to wintry weather over the eastern United States.

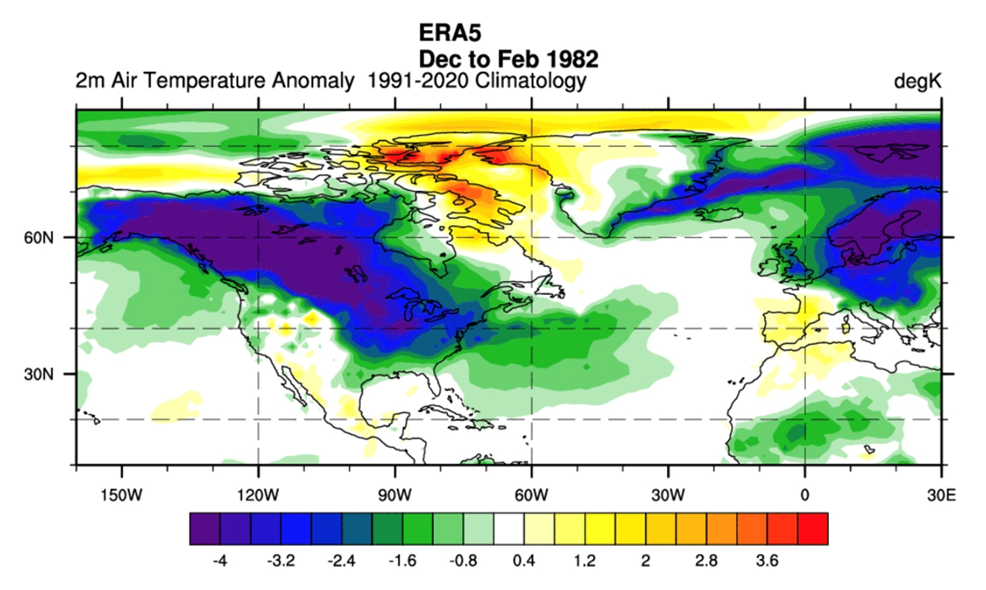

Severe Weather Europe identifies an analog in 1981-82, when a weak polar vortex in early October set the stage for the rest of winter. A high-pressure anomaly settled over the polar regions between December and February.

The low-pressure areas were strong and covered Canada and the United States and extended all the way over the Atlantic.

Looking at the surface temperature analysis for the same period, we can see the expected image: cold air anomalies over much of Canada, expanding into the northern and eastern United States.

Droughts and fires

Category 5 hurricanes, atmospheric rivers, more El Ninos, weakening (and shifting) polar vortices, a slowing AMOC, and the loss of sea ice at both poles are the canaries in the coal mine of a warming planet.

To this we should add a new report describing the world’s “vital signs”, published Tuesday in the journal ‘Bioscience’. It ain’t pretty.

The assessment, prepared by some of the world’s top climate scientists, and building on a previous analysis backed by more than 15,000 scientists, found that 25 of the 35 measurements used to track Earth’s climate risk are at record levels.

“We are on the brink of an irreversible climate disaster,” the authors wrote. “This is a global emergency beyond any doubt.”

For example, as the three charts below show, wildfires and floods are on the rise, and the planet is experiencing more days of extreme heat.

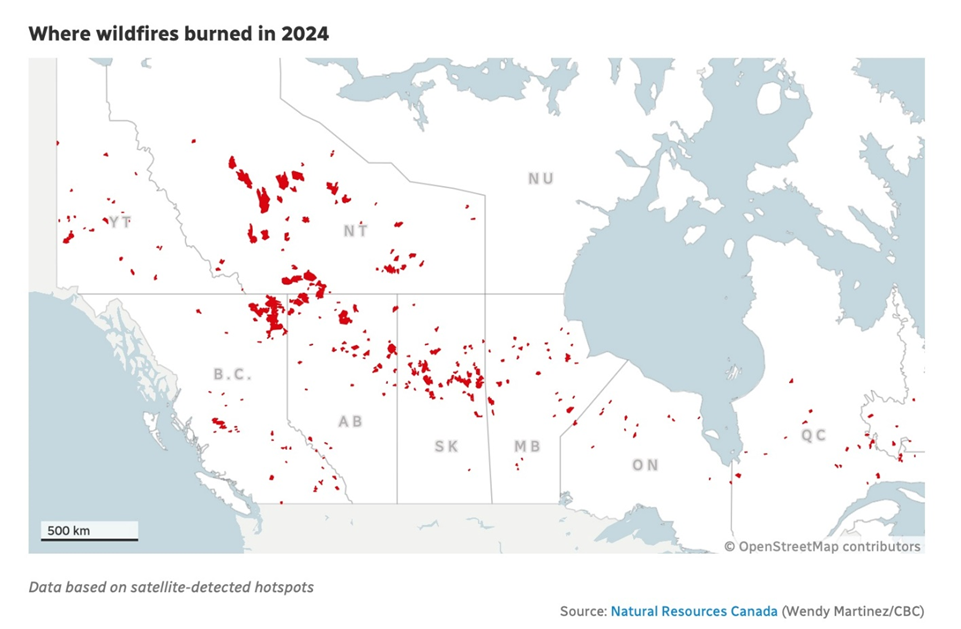

A wildfire in Jasper, Alberta this summer destroyed parts of the town and resulted in $880 million in insured damages. This year’s wildfire season in Canada wasn’t as bad as 2023, but it was still “quietly devastating”.

According to Natural Resources Canada, it was the second-worst wildfire season in terms of area burned since 1995, with more than 5.3 million hectares consumed by fire. Last year, 15 million hectares burned.

Compared to 2023, when most of the country had wildfires, this year most of them were in Western Canada. About 70% of the total areas burned was in BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Northwest Territories.

Research scientist Yan Boulanger with NRC said the 2024 season is consistent with what wildfire scientists have observed over the past 50 years — an increase, decade over decade, in area burned.

Of course the wildfires weren’t confined to North America.

Reuters reported mid-September that South America is being ravaged by fire from Brazil’s Amazon rainforest through the world’s largest wetlands to dry forests in Bolivia, breaking a previous record for the number of blazes seen in a year up to Sept. 11.

Satellite data analyzed by Brazil’s space research agency Inpe has registered 346,112 fire hotspots so far this year in all 13 countries of South America, topping the earlier 2007 record of 345,322 hotspots in a data series that goes back to 1998.

The South American fires are being fanned by a series of heat waves since last year. “We never had winter,” Reuters quoted an air quality researcher at Inpe, of the weather in Sao Paulo, Brazil in recent months. “It’s absurd.”

A drought that began last year in the country has become the worst on record.

The greatest number of fires in September were in Brazil and Bolivia, followed by Peru, Argentina and Paraguay.

Like in Canada, it’s not only the fires but the smoke. The Inpe researcher said fire from deforestation in the Amazon create particularly intense smoke because of the density of the vegetation burning.

“The sensation you get flying next to one of these plumes is like that of an atomic mushroom cloud,” she said.

Another Reuters story in September pointed out low river levels in South America’s rivers as the drought in Brazil spreads.

The Paraguay River, a key transportation corridor for grains, hit a record low in the capital city, Asuncion; Brazil’s drought has hindered navigation along waterways in the Amazon.

The Parana River in Argentina is also near record lows. Both rivers start in Brazil, eventually flowing into the sea near Buenos Aires. Reuters says they are important routes for soy, corn and other goods.

According to grain crushing chamber CAPPRO, “vessels have had to transport volumes below the average of their normal cargo capacity. This has generated delays and made travel times longer.”

Paraguay is the world’s third largest soybean exporter and Argentina is the top exporter of processed soy. A large percentage of both commodities are barged to seaports downriver.

Unfortunately for farmers and traders, the near future doesn’t offer much improvement. Paraguay’s Meteorology and Hydrology Directorate:

[T]he outlook for river levels in the coming months was not encouraging, even with the traditional October-November rainy season ahead…

Less rain than normal is expected in the second half of the year due to the La Nina weather phenomenon, which brings drier, cooler conditions in Paraguay and Argentina, though it usually heralds wetter weather farther north in Brazil.

The global river situation is equally bad. According to the World Meteorological Association, via The Guardian, rivers dried up at the highest rate in decades in 2023, putting water supply at risk:

Over the past five years, there have been lower-than-average river levels across the globe and reservoirs have also been low, according to the World Meteorological Organization’s (WMO) State of Global Water Resources report.

In 2023, more than 50% of global river catchment areas showed abnormal conditions, with most being in deficit. This was similar in 2022 and 2021. Areas facing severe drought and low river discharge conditions included large territories of North, Central and South America; for instance, the Amazon and Mississippi rivers had record low water levels. On the other side of the globe, in Asia and Oceania, the large Ganges, Brahmaputra and Mekong river basins experienced lower-than-normal conditions almost over the entire basin territories…

2023 was the hottest year on record, with rivers running low and countries facing droughts, but it also brought devastating floods across the globe…

Areas that faced flooding included the east coast of Africa, the North Island of New Zealand, and the Philippines.

In the UK, Ireland, Finland and Sweden, there was above-normal discharge, which is the volume of water flowing through a river at a given point in time…

Currently, 3.6 billion people face inadequate access to water for at least one month a year, and this is expected to increase to more than 5 billion by 2050, according to UN Water.

Glaciers also fared badly last year, losing more than 600 gigatonnes of water, the highest figure in 50 years of observations, according to the WMO’s preliminary data for September 2022 to August 2023.

Conclusion

Despite the promises of politicians and certain business leaders who claim to have the answers to stop global warming, the truth is it is unstoppable. The inescapable conclusion? The world will keep warming until it isn’t. We are all on an upward global warming escalator that has no down option. The only question is, how fast will the escalator move?

In 2018 the world’s leading climate scientists warned there are only 12 years to go for warming to be kept to a maximum 1.5 degrees C. If, after a dozen years, not enough is done to slow global warming, a tipping point will be reached, beyond which the risk of droughts, floods and extreme heat, will significantly worsen.

How are we doing with that? Not great. One only has to look at regional climate/ weather maps to see that major changes are taking place before our very eyes.

The issue is often framed as human-caused “climate change”, with the answer to simply cut back on carbon emissions and eventually the planet will heal itself. This is a facile solution that does not incorporate even the most basic tenets of Earth science and geology.

Fortunately, there has been some movement on the side of the “climate change deniers”, many of whom are smart individuals who understand the complex cycles of geological time.

Consider: Scientists have gathered enough clues from Earth’s past climate to graph the average temperature from 485 million years ago to the present.

This new work, which is a described in a Bloomberg opinion piece published by The Deccan Herald, shows temperatures spent hundreds of millions of years bouncing up and down, from climates similar to ours to ones that were steamier by about 15C (30F).

Earlier attempts to chart our planet’s ancient climate suggested vastly hotter average temperatures — 30C (60F) above today’s — that gradually cooled. The new analysis, published this week in Science, instead shows a series of extreme oscillations but no overall trend.

Benjamin Mills, a biogeochemist at the University of Leeds, says very large swings in climate are the norm for the planet, and that they have been driven “very clearly” by changes in CO2 concentration.

The swings have never been enough to destroy life completely, except for about 250 million years ago, when a “mass extinction event” snuffed out about 70% of land species and 90% of marine species. The culprit, says the article, was a series of volcanic eruptions that caused carbon dioxide levels to spike.

The new analysis shows Earth repeatedly jumped between a sweltering 30C state, known as a greenhouse, and the cooler state, around 15C, known as the ice house. “Right now, we’re actually in an ice-house Earth,” said Jessica Tierney, a paleoclimatologist and a co-author of the paper. Our average temperature is around 15C and, for now, we still have thick ice on Greenland and Antarctica.

And there it is. Would someone please tell the politicians and the mass media that we are still living in an ice age?

For proof of the dramatic swings of climate and temperature that mark Earth’s history, one only has to look underfoot. The article notes that scientists have long known about past hot spells from the fossil record, which showed that crocodiles once roamed the Arctic and that palm trees grew in Antarctica. In 2008 a shipwreck laden with gold coins was discovered in a desert in Namibia. Fossils of dead sea creatures have been found at the summit of Mount Everest — evidence that sedimentary rock which formed the bottom of an ancient ocean was thrust up nearly 9,000 meters by plate tectonics.

Considering the fact, not the theory, that global warming is going to happen regardless of what humanity does to try and prevent it, it’s worth asking: Instead of trying to slow climate change, wouldn’t we be better off cleaning up the planet best we can, and preparing for the worst consequences of warming?

New set of priorities needed for unstoppable global warming

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Share Your Insights and Join the Conversation!

When participating in the comments section, please be considerate and respectful to others. Share your insights and opinions thoughtfully, avoiding personal attacks or offensive language. Strive to provide accurate and reliable information by double-checking facts before posting. Constructive discussions help everyone learn and make better decisions. Thank you for contributing positively to our community!

1 Comment

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

#HurricaneMilton #GlobalWarming #ClimateChange #drought #WildFires