For industrial metals exploration, it’s game on

2021.06.28

As countries continue to vaccinate their populations, and infections drop due to earlier lockdowns, travel restrictions and social distancing, economies are slowly re-opening, stoking demand for cars, electronics, clothing, and infrastructure for urban renewal, like new roads, bridges and water systems.

The US economy is running hot, owing to massive federal stimulus and a waning coronavirus pandemic, and that has caused demand for goods and services to outstrip the ability of companies to supply them.

Toss in virus-related supply chain bottlenecks, including a shortage of labor in some industries, causing wages to rise, and we have the biggest inflation increase in 13 years — +5%.

China, the world’s second biggest economy and the top commodities consumer, has emerged from the pandemic relatively unscathed. Industrial production surged 6.6% in May and first-quarter GDP rose an astonishing 18.3%, the most since China began keeping quarterly records in 1992.

That explains why the prices of industrial metals are enjoying such a spectacular run, especially given that some, like copper and zinc, are facing shortages, something we at AOTH have been talking about for years.

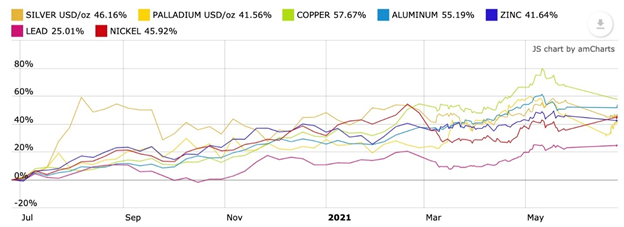

As the chart below shows, copper, silver, zinc, lead, nickel, aluminum, and palladium have all witnessed substantial gains over the past year.

Industrial metals

Industrial metals are relatively common in the Earth’s crust, and less expensive and easier to mine than precious metals.

However, while the prices of, say, copper and nickel, are lower than silver and gold, industrial metals play an extremely important role in the world economy due to their many applications.

Copper is utilized in so many industries, such as construction, transportation, and telecommunications, it has become a leading indicator of economic growth. Its ability to predict future economic conditions has earned it a “PhD in economics”, hence its nickname “Dr. Copper”.

If demand for copper is growing and prices are rising, usually the economy is improving. Conversely, falling copper prices signal a warning that economic activity is slowing in areas such as homebuilding.

Base metals are non-ferrous, meaning they do not contain iron. The most common are copper, lead, nickel, tin, aluminum and zinc.

While copper carries the most weight in terms of importance to the global economy, aluminum is the most-traded base metal on the London Metal Exchange (LME). The lightweight metal is extremely malleable; it can be pressed into sheets and made into containers for food and other products.

Zinc is the fourth most used metal today in terms of annual tonnage produced. Zinc’s main function is to galvanize metals. Adding a zinc coating to steel or iron protects it against rusting. A high percentage of steel that goes into buildings and automobiles is galvanized with a zinc coating, making it a highly prized metal.

Zinc is also frequently used in die-casting, is a common ingredient in coins, and has applications in construction, including pipes and roofing.

The majority of the world’s zinc deposits contain lead, meaning lead and zinc are often mined together. The zinc mineral sphalerite is usually associated with galena (the lead mineral) and chalcopyrite (a copper mineral).

Nickel’s biggest use, about 65%, is in alloying, particularly with chromium and other metals to produce stainless and heat-resistant steels. More recently, nickel sulfate powder (made from nickel sulfide ore) has become a key ingredient in cathodes for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles.

For the purposes of this article, we are including iron ore as an industrial metal, and silver, which has both monetary and industrial applications.

Iron ore

Iron ore is the raw material from which crude iron, also known as pig iron, can be economically extracted. Nearly all of the world’s mined iron ore is used to make steel, which is an essential part of our modern infrastructure (structures, automobiles, machinery, etc.).

To produce one tonne of steel, roughly 1.5 tonnes of iron ore are required. The higher the iron content, the higher it is graded and the more valuable it becomes.

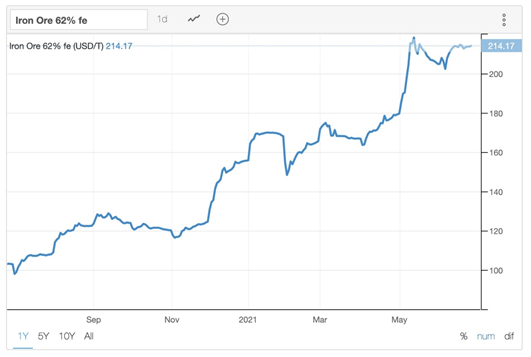

Earlier this year, iron ore prices broke a new record amid a sustained rally in commodities, as demand from top consumer China remains as robust as ever.

According to Trading Economics, benchmark 62% Fe fines imported into Northern China (CFR Qingdao) are now changing hands for $214 per tonne – more than double from a year ago.

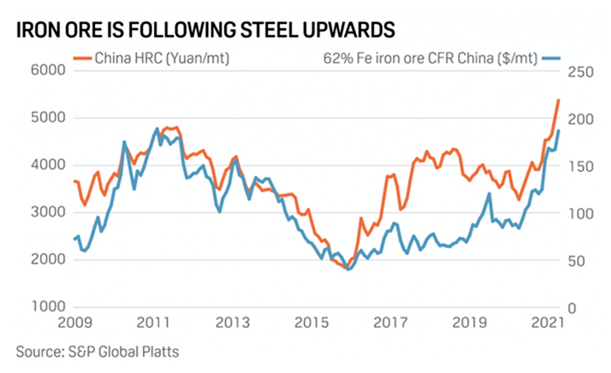

At the center of the rally is rising steel prices, from Asia to North America. Steel demand remains strong as economies — China in particular —continue their massive investments in steel-intensive infrastructure.

Because China’s domestic iron ore supply is relatively low-grade and expensive to process, many steelmakers there find it cheaper and more efficient to import high-grade iron ore.

China consumes more iron ore than any other nation, as it is by far the world’s biggest steel producer. In fact, its output is greater than all the other steelmaking countries combined.

According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the country churned out a record 1.05 billion tonnes of crude steel in 2020 — 6% more than 2019 — with “demand boosted by Beijing’s stimulus measures for infrastructure such as bridges and roads and both new commercial and residential buildings.”

This year, steel output from Asia’s leading economy is set to surpass that total.

The Metallurgical Industry Planning and Research Institute is projecting a 1.4% rise to 1.065 billion tonnes in 2021, implying a corresponding increase in China’s iron ore demand to meet that output.

The World Steel Association forecasts global steel demand to grow 5.8% this year, surpassing pre-pandemic levels, followed by another 2.7% increase the year after. China’s consumption, about half of the global total, will keep growing from record levels.

Silver

As vaccinations continue and more countries open up, the increased demand for manufactured goods including solar power cells and electronics will be a boon for silver.

More and more silver is being demanded for use in solar photovoltaic (PV) cells, as countries move towards adopting renewable energy sources.

As the metal with the highest electrical and thermal conductivity, silver is ideally suited to solar panels. Silver paste within the solar cells ensure the electrons move into storage or towards consumption, depending on the need.

5G technology is set to become another big new driver of silver demand.

Among the 5G components requiring silver, are semiconductor chips, cabling, microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), and Internet of things (IoT)-enabled devices.

The Silver Institute expects silver demanded by 5G to more than double, from its current ~7.5 million ounces, to around 16Moz by 2025 and as much as 23Moz by 2030, which would represent a 206% increase from current levels.

A third major industrial demand driver for silver is the automotive industry.

A recent Silver Institute report says battery electric vehicles contain up to twice as much silver as ICE-powered vehicles, with autonomous vehicles requiring even more due to their complexity. Charging points and charging stations are also expected to demand a lot more silver.

According to SI, silver’s use in the automotive market will see a strong rebound in 2021, to just over 60Moz. It estimates the sector’s demand for silver will rise to 88Moz in five years as the transition from traditional cars and trucks to EVs accelerates. Others estimate that by 2040, electric vehicles could demand nearly half of annual silver supply.

Finally, silver demand for “printed and flexible electronics” is forecast to increase 54% over the next nine years, rising from 48Moz in 2021 to 74Moz in 2030, meaning a consumption of 615Moz during this time frame.

A recent Silver Institute news release describes them as “mainstays” in a variety of electronic products, including sensors that measure everything from temperature, pressure and motion, to moisture, relative humidity and carbon monoxide. They are also used in medical devices, mobile phones, appliance displays and consumer electronics.

The sector generates about $57 billion a year in annual revenues and is expected to grow 11.1% through 2025.

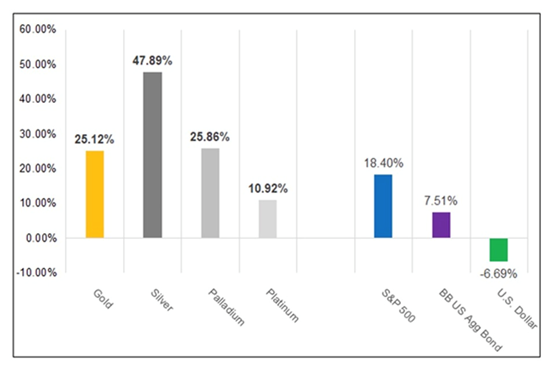

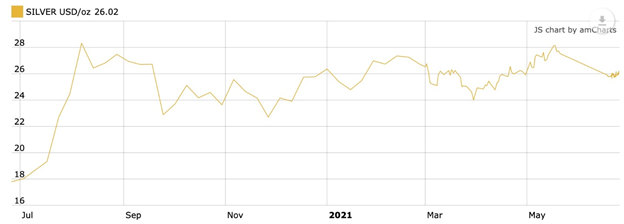

Spot silver jumped to $28.32 an ounce in August 2020, its best performance in seven years, and though the price retreated last fall, it finished the year up an impressive 47%, more than doubling gold’s 25% gain.

Lately, silver has followed gold on a downward trend, but the white metal has preserved most of its gains, currently sitting at $26.02 an ounce compared to $17.80 a year ago.

In fact the silver outlook is extremely positive due to a combination of strong monetary and industrial demand drivers.

According to the 2021 World Silver Survey, global demand for silver this year is expected to outpace supply by 7% (+ 8% supply vs +15% demand).

Demand will be led by investments in industrial and investment-grade physical silver, as a result of economic recovery from the pandemic, as well as healthy coin and bar purchases building on 2020’s gains.

The Silver Institute therefore expects the silver price to advance a whopping 33% in 2021.

Copper

As the third most-consumed metal on Earth behind iron ore and aluminum, copper is all around us. Found naturally in the Earth’s crust, copper was among the first metals used by early humans, dating back to the 8th century BC.

Copper is an essential metal needed for the functioning of a modern economy and for the green economy of the future, which includes electric vehicles (EVs), smart grids, and 5G networks. EVs contain about four times as much copper as regular vehicles.

Just under half of copper demand is from the electronics industry. The rest is used to feed a range of industrial machinery, vehicles, and consumer products. For most, no other raw material can be substituted for copper.

Copper is useful for electrical applications because it is an excellent conductor of electricity, and cheaper than gold or silver (also both conductors). That, combined with its corrosion resistance, ductility, malleability, and ability to work in a range of electrical networks, makes it ideal for wiring. Among the electronic devices that use copper are computers, televisions, circuit boards, semiconductors, microwaves, and fire prevention sprinkler systems.

In telecommunications, copper is used in wiring for local area networks (LAN), modems, and routers. While aluminum is preferred for overhead power transmission lines, copper wires are used in medium-voltage distribution and low-voltage connections.

The construction industry would not exist without copper; it is essential for wiring in residential and commercial structures. The red metal is also used for potable water and heating systems due to its ability to resist the growth of water-borne organisms, as well as its resistance to heat corrosion.

The transportation industry is reliant on copper for core components of aeroplanes, trains, cars, trucks, and boats. A commercial airliner has up to 190 kilometers of copper wiring, while high-speed trains use up to 10 tonnes of copper per kilometer of track. Automobiles have used copper and brass radiators and oil coolers since the 1970s. Most new vehicles need copper for on-board navigation, anti-lock braking systems, heated seats, defrosting wires embedded in windows, hydraulic lines, and wiring for window and mirror controls.

China is by far the largest copper consumer, every year receiving around half of the world’s copper shipments.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) envisions a vast network of railways, pipelines, highways, and ports that extend west through the mountainous former Soviet republics and south to Pakistan, the Middle East, India, and southeast Asia. Research by the International Copper Association found that the BRI is likely to increase demand for copper in over 60 Eurasian countries to 6.5 million tonnes by 2027, a 22% increase from 2017.

According to a report by McKinsey Global Institute, general copper demand could grow to 31 million tonnes by 2035, a 43% increase from today’s 22 million tonnes (Mt).

Total mined production in 2019 was just 20Mt, according to the US Geological Survey.

How to bridge the gap? The problem is that existing copper mines aren’t able to crank out as much production needed to ensure that all the demand bases are covered. Additionally, without major new mines up and running to replace the ore that is being depleted from existing copper mines, the industry is looking at a 15-million-tonne supply deficit by 2035.

Some of the largest copper mines are seeing their reserves dwindle and are having to dramatically slow production due to major capital-intensive projects to move operations from open pit to underground. Copper grades are declining, making mining more expensive, especially in Chile, the world’s number one producer.

The copper “pipeline” is the lowest it’s been in a century, and not improving. New supply is concentrated in just five mines – Chile’s Escondida, Spence, Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama, and Kamoto in the DRC. Both countries are prone to resource nationalism, with Chile suffering the social effects of stark inequality, and the DRC government seen as unstable and rife with corruption.

In 2018 the DRC raised taxes and royalties on copper and cobalt – of which the Congo is the top producer – amid fierce opposition from miners.

Exploration for new copper deposits that are large and high-grade enough to be economically brought into production is therefore of primary importance to the mining industry; especially since the demand side of the equation is only going to get stronger.

With China returning to growth following a rough patch during early 2020, when millions were forced into lockdown, Dr. Copper, true to form, has performed remarkably well.

From one year ago, copper is up 57%!

The main factors driving prices higher are increased Chinese orders amid a strong manufacturing sector, post-pandemic; a return to growth following a disastrous 2020; trillions in promised green and blacktop infrastructure spending particularly in the US, Europe, and China; and supply disruptions resulting from covid-19-related mine closures.

Nickel

Nickel is present in over 3,000 different alloys, used in over 300,000 products for consumer, industrial, military, transportation, marine and architectural applications.

Nickel’s biggest use, about 65%, is in alloying – particularly with chromium and other metals to produce stainless and heat-resisting steels.

Another 20% is used in other steels, non-ferrous alloys (mixed with metals other than steel) and super alloys (metal mixtures designed to withstand extremely high temperatures and/or pressures, or have high conductivity) often for highly specialized industrial, aerospace and military applications.

About 9% is used in plating to slow down corrosion and 6% is for other uses, including printing coins. Rechargeable nickel-hydride batteries are used in cell phones, video cameras, and other electronic devices. Nickel-cadmium batteries are used to power cordless tools and appliances.

In many of these applications there is no substitute for nickel without reducing performance or increasing cost.

Most recently, nickel sulfate powder made from nickel sulfide ore, is a crucial ingredient in cathode formulation for lithium-ion batteries needed to propel electric vehicles.

Nickel is popular with EV battery-makers because it provides the energy density that gives the battery its power and range. Increasing the amount of nickel in a battery cathode ups its power/ range but, add too much of it and the battery becomes unstable, ie. vulnerable to overheating and a shortening of its lifespan.

According to CRU, current global primary nickel demand was approximately 2.2 million tonnes per annum for 2018 and is expected to grow to 2.8 million tonnes by 2023. Mined nickel production in 2020 was only 2.5 million tonnes, meaning if the market doesn’t see an annual supply increase of at least 300,000 tonnes in the next two years, it will slip into deficit. (the market not only has to supply enough nickel to meet stainless steel demand, but an expected 7-fold increase in demand from EV batteries)

Glencore CEO Ivan Glasenberg recently said nickel supplies need to grow by an additional 250,000 tonnes a year, and he projected annual nickel demand will rise from 2.5 million tonnes currently to 9.2Mt, over the next few decades.

Historically, most nickel was produced from sulfide ores, including the giant (>10 million tonnes) Sudbury deposits in Ontario, Norilsk in Russia and the Bushveld Complex in South Africa, known for its platinum group elements (PGEs). However, existing sulfide mines are becoming depleted, and are not being replaced, which has changed the geographical weighting of nickel production.

Nickel miners are having to go to the lower-quality, but more expensive to process, as well as more polluting nickel laterites such as found in the Philippines, Indonesia and New Caledonia.

Producing nickel-rich battery cathodes requires high-purity nickel, in the form of nickel sulfate, derived from ‘Class 1’ nickel sulfide deposits. This nickel can be processed at relatively low cost, and with minimal waste, using a simple flotation technique.

China says it has found a way to make “green” nickel chemical for EV batteries from nickel laterite deposits in Indonesia that could help to alleviate the coming supply deficit in the metal that is essential to electric vehicle batteries.

Don’t be fooled. The process is extremely polluting, and “ocean tailings ponds” are anything but green. Thankfully car companies aren’t buying it.

Future nickel supply for battery-making is therefore unlikely to come from Indonesia or anywhere else where nickel laterites are mined.

According to BloombergNEF, demand for Class 1 nickel is expected to out-run supply within five years, fueled by rising consumption by lithium-ion electric vehicle battery suppliers.

Where will mining companies look for new nickel sulfide deposits, from which the extraction of high-grade nickel needed for battery chemistries is economically, technically and environmentally feasible? The pickings are slim.

Decades of under-investment equals few new large-scale greenfield nickel sulfide discoveries. Only one nickel sulfide deposit has been discovered in the past decade and a half, Nova-Bollinger in Western Australia.

The result of such limited nickel exploration is a very low pipeline of new projects, especially lower-cost sulfides in geopolitically safe mining jurisdictions. Any junior resource company with a sulfide nickel project will therefore be extremely attractive to potential acquirers.

Zinc

Zinc has risen in importance and value thanks to its fundamental role in clean energy applications. The base metal can be used as anode material for batteries, making it a key part of energy storage systems as we move towards a world of renewables.

According to the International Zinc Association (IZA), annual demand for zinc in batteries was 600 tonnes in 2020, but that figure is projected to leap to 77,500 tonnes by 2030.

Demand from China remains strong, as industrial activity ramps up in the world’s biggest metals consumer and number one electric vehicle market.

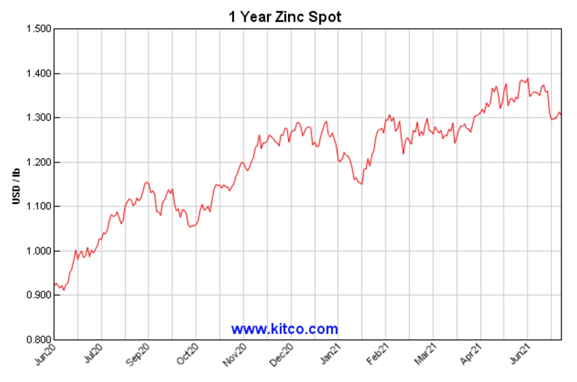

The same can be said for the rest of the world, as nations begin to put the covid-19 pandemic behind them and invest more in their civic infrastructure. The elevated demand is reflected in the metal’s price movements: Following last March’s low of $0.83/lb, spot zinc went on a run and was trading at a three-year high in May, 2021.

A Fitch Solutions report last year pointed to an annual growth rate of 1.1% in global zinc consumption for the next decade, enough to sustain a market deficit given the dwindling supply.

A study published by the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG) showed that the global refined zinc market registered a supply deficit of 480,000 tonnes for the first 10 months of 2020. A combination of soaring demand and recent mine shutdowns could cut zinc supply by another 15%, the group warned.

ILZSG data from the first quarter shows mined zinc production of 3.15Mt unable to keep up with demand of 3.41Mt.

The group predicts global zinc prices will firmly remain over $2,750 per tonne ($1.24/pound) for the rest of the year, on a declining surplus, supply disruptions including smelting operations, and recovery in the world economy, particularly China, where the government is investing heavily in infrastructure programs requiring raw and finished metal products including galvanized steel containing zinc.

The supply picture for zinc is indeed rather bleak.

Over the years, some very large zinc mines have been depleted and shut down. These include MMG’s Century mine, which used to supply 4% of the world’s zinc, and Glencore’s Brunswick and Perseverance mines in Canada.

Yet there have been few discoveries or big zinc projects planned, setting the zinc market up for a supply shortage.

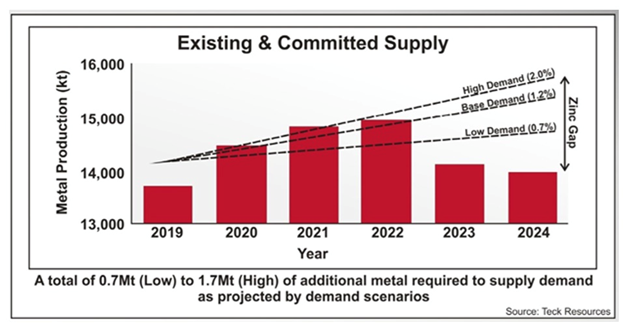

Beginning in 2021, demand growth is already expected to outpace any increase in production, says Russian copper and zinc producer UGMK.

UGMK estimates world zinc production this year to rise 2.9% to 14Mt as Chinese plants continue to ramp up output in the face of solid domestic demand, but its demand growth forecast of 4.2% means the current global zinc surplus is likely to shrink in 2021.

The company also says global zinc ore extraction at existing mines will reach a peak in 2024, just exceeding the 14Mt mark. Extraction is likely to enter a stage of decline thereafter as ore quality deteriorates and certain reserve fields come to the end of their lives.

Furthermore, projects aimed at resource base replenishments will not suffice to meet the growing demand for zinc ore, according to UGMK. Over the 2025-2030 period, the market “may well be facing a deficit in zinc concentrate production,” it adds.

Thus, it cannot be stressed enough just how crucial a large discovery is to the future zinc supply chain.

Currently one of the critical minerals highlighted by both the Canadian and US governments, zinc will surely be near the top of policymakers’ agendas when it comes to resource security, and this starts with support for domestic projects.

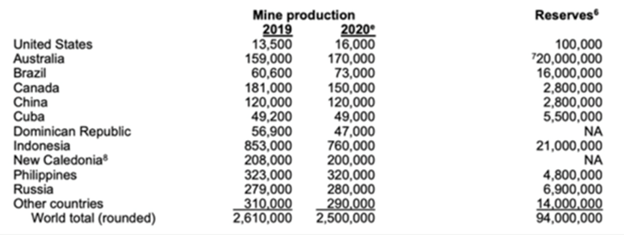

According to the US Geological Survey, zinc is mined in over 50 countries worldwide, but the vast majority of global supply comes from China, Australia and Peru.

Canada, too, has historically been near the top of the zinc producers list. The abundance of SEDEX Zn-Pb-Ag deposits, the most prevalent source of zinc, makes places like British Columbia’s Kechika Trough region an ideal ground for the nation’s next mine.

The BC Geological Survey has identified as many as 4,510 zinc occurrences within the province.

Tin

Tin is traditionally used as a solder and for tin plating of other metals, but it has also become a key metal in new applications such as autonomous and electric vehicles, renewable energy, energy storage and advanced computing.

With the world recovering from the covid-19 pandemic and nations setting their sights on a new “green economy”, demand for tin is expected to remain healthy and trend upwards for years. So too should its price.

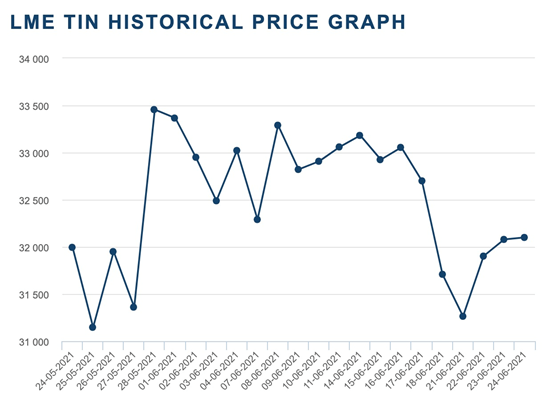

Like other base metals, the price of tin has been rising like never before over the past year on relentless infrastructure spending by governments (ie. China). Year to date, the metal has gone up by 47% — now trading above $30,000 a tonne for the first time in a decade.

Tin currently has the highest value of the major base metals, more than triple the value of copper and eleven times the price of zinc.

Chances are the value of tin could stay high for a while.

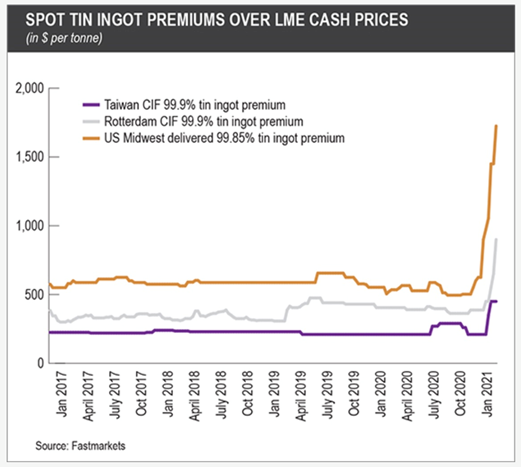

Earlier in the year, the London Metal Exchange (LME) experienced a chronic squeeze on spreads between futures and cash tin prices, during which the market witnessed the biggest cash to three-month premium since 1990.

Tightening supply and a rush for physical metal both played a part.

It seems as though many parts of the world have run out of the metal essential for circuit-board soldering and critical for clean energy applications.

The domino effect of the tin market squeeze is that China — the world’s largest producer but traditionally a net importer of the refined metal — has to step up as the supplier of last resort.

In the first quarter of 2021, China exported 2,151 tonnes, already half of last year’s count, Reuters reports.

The high-price environment may have provided an incentive for producers to export, but this hasn’t been the case for Indonesia, the world’s largest tin exporter. For the first three months, shipments from Indonesia declined 24%, extending a downtrend that has been running since 2018.

Over the course of 2020, the Southeast Asian nation has struggled to produce enough of the base metal to satisfy global appetites. Output from Indonesian state producer PT Timah plunged 40% to 45,700 tonnes last year, according to Fastmarkets.

As the global economy continues to recover, demand for tin this year is projected to rise 6% to 361,500 tonnes, the International Tin Association says.

With supply disruptions and soaring demand on full display in London, sooner or later, the world’s scramble for tin could open the door for places that are historically rich in base metals, to become an integral part of the metal’s supply chain.

Palladium

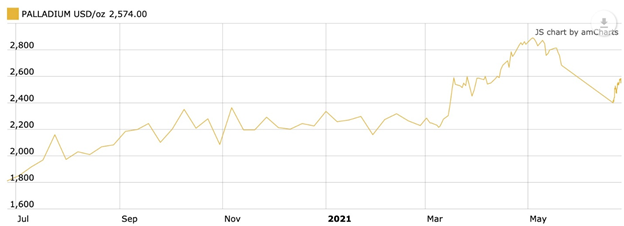

As the world transitions from fossil-fueled “ICEs” to battery-powered electric vehicles, the internal combustion engine is unlikely to be resigned to the scrap heap, just yet. Gasoline vehicles and gas-electric hybrids will gradually displace more-polluting diesels, the former equipped with catalytic converters to filter out pollutants like NoX and particulate matter.

This means growing demand for materials that go into gas-powered autocatalysts, including palladium.

The platinum group metal is set for a supply squeeze for the 10th straight year. Driving palladium demand are higher sales of gasoline vs diesel units and tighter pollution controls.

Palladium use in hybrid vehicles, seen as a bridge between gas-powered cars and pure electrics, is a growing source of demand. The lustrous metal is also used in electronics, surgical instruments, jewelry, watch making, aircraft spark plugs, hydrogen purification and groundwater treatment.

Supply, meanwhile, is being challenged by production disruptions, for example flooding at Arctic mines.

On May 4 palladium hit a new record of $2,890/oz. Over the past year, Pd is up a sizzling 42%.

Exploration acceleration

The higher prices of industrial metals, which are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future due to steady demand, and the above-mentioned supply issues, are prompting a number of major miners to step up their exploration game.

Earlier this week it was reported that BHP, the world’s largest mining company, is looking to double its base metals exploration budget within five years.

According to a June 23 Reuters story, BHP’s board is expected to make a call on its Jansen potash project in Canada as the miner looks to raise its exposure to new economy minerals including copper and nickel, seen as cornerstones of the world’s transition towards cleaner energy.

The diversified miner has already partnered with a junior, Midland Exploration, to hunt for nickel in the Nunavik region of northern Quebec, has a joint venture on copper concessions in Ecuador with Luminex Resources, and holds a 12.5% stake in SolGold, whose Cascabel-Alpala copper-gold project in Ecuador is slated to start producing in 2025.

In March, BHP said it would move its head office for exploration from Santiago, Chile to Toronto, “to be closer to the action,” Reuters quoted chief technical officer, Laura Tyler, saying. The quote is a reference to growing BHP’s pipeline of green metals projects, particularly copper and nickel.

Rival Rio Tinto has also been moving in the same direction, with the major miner announcing in April it has started exploring its Solwezi copper project in Zambia.

The work plan includes more than 5,000 meters of diamond drilling, nearly 3,000m of air core drilling, 1,600m of reverse circulation drilling, along with mapping to test a +10-km copper soil anomaly.

Solwezi is located on the Zambia-DRC copper belt, adjacent to Africa’s largest copper mining complex, First Quantum’s Kansanshi.

This week, Rio said its 2021 exploration program at Casino, a copper-gold project in Canada’s Yukon Territory, will involve a five-hole, 1,500m drill campaign. The program is designed to confirm resources and the lithological and mineralogical setting of the deposit’s eastern and southern margins.

There will also be soil sampling to check for a second porphyry deposit, and robotic drill core scanning including “LIDAR” (Light Detection and Ranging) scanning, XRF analysis, hyperspectral analysis and some geotechnical analyses.

Coeur Mining, which has five producing mines — three in the US, one in British Columbia and the fifth in Mexico — along with two development projects, recently said it plans to shatter its own record for exploration spending this year.

The New York-listed company has already completed over 100,000 meters of drilling at its Silvertip silver-zinc-lead mine in BC, currently under suspension, and its Crown gold project in Nevada. Coeur expects to spend $68 million in exploration in 2021, up 30% from last year.

Looking at the big picture, exploration spending unsurprisingly fell last year due to all of the restrictions imposed by governments due to covid-19, and low metals prices caused by a sudden demand shock in the early days of the pandemic.

According to S&P Global Market Intelligence’s World Exploration Trends report, the global budget for non-ferrous metals exploration fell 11%, from $9.8 billion in 2019 to an estimated $8.7B in 2020.

However, “The decline in the 2020 exploration budget was far less steep than initially anticipated at the end of the March quarter when the global spread of covid-19 was surging,” Mark Ferguson, research director at S&P Global Market Intelligence, said in a media statement.

Of the $8.7 billion, over half was budgeted for gold exploration, while copper ventures received 21% of the total and zinc/lead projects got 5%. The gold budget increased by a modest 1% while the budgets for industrial metals, including copper, zinc, lithium and cobalt, all saw declines.

Major miners dominated exploration spending, at $4.4 billion, compared to $2.54B for juniors, $1.05B for mid-tiers and half a billion for governments.

One piece of good news involved financings. According to the report, juniors and mid-tiers successfully raised $11.2 billion last year, the most since 2012.

As for what’s in store, World Exploration Trends expects 2021 will be better for mineral exploration than 2020, likely reversing pandemic-related losses, and then some.

“Should metal prices continue to remain strong over the next several months, it is likely that the 2021 exploration budget will be stronger, rising by 15%-20% year over year,” Ferguson predicted.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.