Copper: the linchpin of ancient and modern society we need to find a lot more of

2021.04.17

As the third most-consumed metal on the planet, behind iron ore and aluminum, copper is all around us. Found naturally in the Earth’s crust, copper was among the first metals used by early humans, dating back to the 8th century, BC.

Three thousand years later homo sapiens figured out how to smelt copper from its ore, and to alloy it with tin to create bronze. Bronze was useful for tools and weapons, making it one of the most important inventions in the history of civilization.

The Copper Age

Nothing happens without copper; as it turns out, not even civilization itself. Beginning around 5,000 BC, the “Chalcolithic” (from the Greek “khalkos” for copper and “lithos” for stone) or Copper Age was a transitionary period between the Neolithic (Stone Age) and the Bronze Age.

It was during this time that copper was introduced as a material that could be worked into metal, paving the way towards the use of bronze later on.

Before that, utilitarian stone objects were fashioned out of flint, mined in small (by today’s standards) underground caverns using rudimentary tools. In England between 2,500 and 3,000 BC, ancient miners employed picks shaped from antler bones to get at the glassy black rock which could be broken into sharp pieces used for example to build houses or canoes.

The archeological site of Belovode in present-day Serbia holds the distinction as the world’s oldest copper-smelting location, circa 5,000 BC. Copper was also found in the Near East beginning in the late 5th millennium BC. Later, pockets of copper technology began appearing in northern Italy and along the Mediterranean coast.

Eventually, ancient prospectors moved north, bringing their way of life and then-radical metalworking technology with them. So much of what have today is made of metal, but 4,500 years ago, there was nothing but crude dwellings and monuments built of stone and earth. The arrival of metal catapulted early Britain and other societies, including China, which has a long history of using metal objects, into a whole new chapter of civilization.

In the British Isles, the first copper mines were dug into the hills of southwestern Ireland. There, on the shores of an ancient lake, green and blue oxidized rocks betray the tell-tale signs of copper mineralization.

Neolithic people noticed the host limestone rocks were streaked with glittering copper minerals, but without knowledge of mining, little was done with them. It wasn’t until these first Britons came into contact with people from Europe, that mining and smelting copper began.

Some of the earliest copper axes can be traced to the Ross Island copper mine in Ireland. Archeologists found stone hammers with grooves in the center used to attach wooden handles, that pounded the rock into tiny pieces. Ancient metal workers used bellows to heat fires to a high enough temperature to melt the rock into glowing metal that, when cooled, hardened into copper that was shaped into tools and decorative objects.

Copper axes from this period were circulated all over Ireland and into western Britain, suggesting the beginnings of the first trade routes.

The Copper Age brought with it a social as well as a technological revolution. The raw material found in the hills of Ireland, and the technology that transformed it into copper are, in many ways, the very foundations of our modern world.

The “Beaker” people, named from the pottery vessels they buried their dead with, brought a new culture from central Europe that spread across Britain. The UK’s oldest metal objects were identified in a grave known as the Amesbury Archer, located in Wiltshire around 2,300 BC.

The fact that the individual was buried with copper knife blades, a “cushion stone” used for finishing metal, and gold jewelry, suggests an individual who knew how to get metal and how to work metal.

The grave is also significant because it shows for the first time, people were buried as individuals, with grave goods, suggesting a strong sense of self. Copper Age graves also conferred status.

For early Britons this would’ve been radical thinking. It compares to stone-age Britain, when people were buried in communal tombs, and which reached its peak in cosmically aligned monuments, like Stonehenge.

Copper may have looked good but it was soft, therefore little better than flint as a cutting or a pounding tool.

The Beakers also knew about tin, which was unlocked from rocks on the coast of Cornwall. Combing copper with the tin mineral cassiterite yielded bronze, which was to propel Britain from the fringes to the technological forefront of Europe.

Controlling the bellow speed to reach the perfect temperature for casting, early metal workers knew how using just the right mixture of metals could make an alloy that was hard enough to make useful, durable tools and weapons like swords.

But first came bronze axes, which were collected as objects of status. Indeed, for the first time since the Stone Age, there was a way of getting and demonstrating wealth.

Metals began moving all over the country — for example axes found in Scotland were made from Cornish tin and Irish copper — and a new class of people emerged to control metals production and trade. It’s estimated around a quarter of the population at that time was involved in this economic activity, with some of them becoming fabulously rich.

During the Bronze Age, natural harbors and rivers that facilitated trade became important geographical features. To trade with Europe, Britons built boats that were sailed or rowed to the continent.

In 1992 a wooden boat was found buried 20 feet underground in layers of mud. Originally thought to be up to 20 meters long, the “Dover Boat, Kent” find, is the oldest surviving sea-going vessel in the world.

By 1,500 BC Britain was a rich, connected land but one aspect hadn’t changed much at all: farming. Most of the population still moved around with the crops and seasons, with little evidence of permanent farms.

This thinking changed in the 1980s with the discovery of the Flag Fen village in Cambridgeshire. This group of Bronze Age roundhouses served as a template for domestic living that lasted for over a thousand years.

The archeological evidence suggests Bronze Age people were peaceful and well-nourished from a decent diet. They lived in families and farmed small plots of land.

As the Bronze Age matured, this settled lifestyle led to the very first villages, with houses close together and surrounded by fields. Indeed, the Bronze Age changed the way we related to a place and one another – the idea of living in the same house your whole life, working a plot of land and having permanent neighbors. Up to about 1,500 BC this was shockingly new.

Eventually the Bronze Age succumbed to the Iron Age, and in Britain the glories of Celtic warriors, druids, and kings, then finally the Romans, the building of towns, and the end of pre-history.

The late Bronze Age marked a massive turning point; it was as if we had come of age and could mold the world in our own image. And to think it all started with copper.

Modern-day usage

Sometimes referred to as “Dr. Copper” for its ability to diagnose the state of the global economy, copper is just as essential to modern society as to ancient civilizations — if not more so.

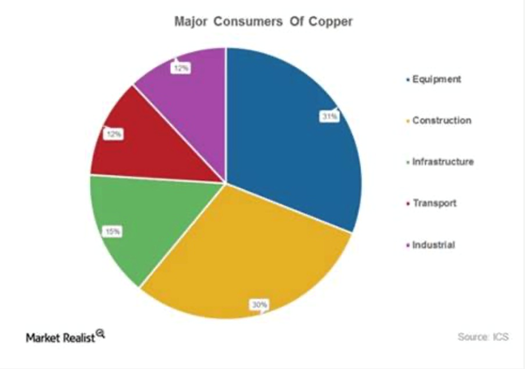

The Copper Development Association divides its uses into four categories: electrical, construction, transport and other. By far the largest sector for copper usage is electrical, at 65%, followed by construction at 25%.

Copper is useful for electrical applications because it is an excellent conductor of electricity.

That, combined with its corrosion resistance, ductility, malleability, and ability to work in a range of electrical networks, makes it ideal for wiring. Among electrical devices that use copper, are computers, televisions, circuit boards, semiconductors, microwaves, and fire prevention sprinkler systems.

In telecommunications, copper is used in wiring for local area networks (LAN), modems and routers. The construction industry would not exist without copper; it is essential for wiring in residential and commercial construction. The red metal is also used for potable water and heating systems due to its ability to resist the growth of water-borne organisms, as well as its resistance to heat corrosion.

The transportation industry is reliant on copper for core components of airplanes, trains, cars, trucks and boats. A commercial airliner has up to 190 kilometers of copper wiring, while high-speed trains use up to 10 tonnes of copper per kilometer of track.

Automobiles have used copper and brass radiators and oil coolers since the 1970s. More recent applications include on-board navigation, anti-lock braking systems, heated seats, defrosting wires embedded in windows, hydraulic lines, and wiring for window and mirror controls.

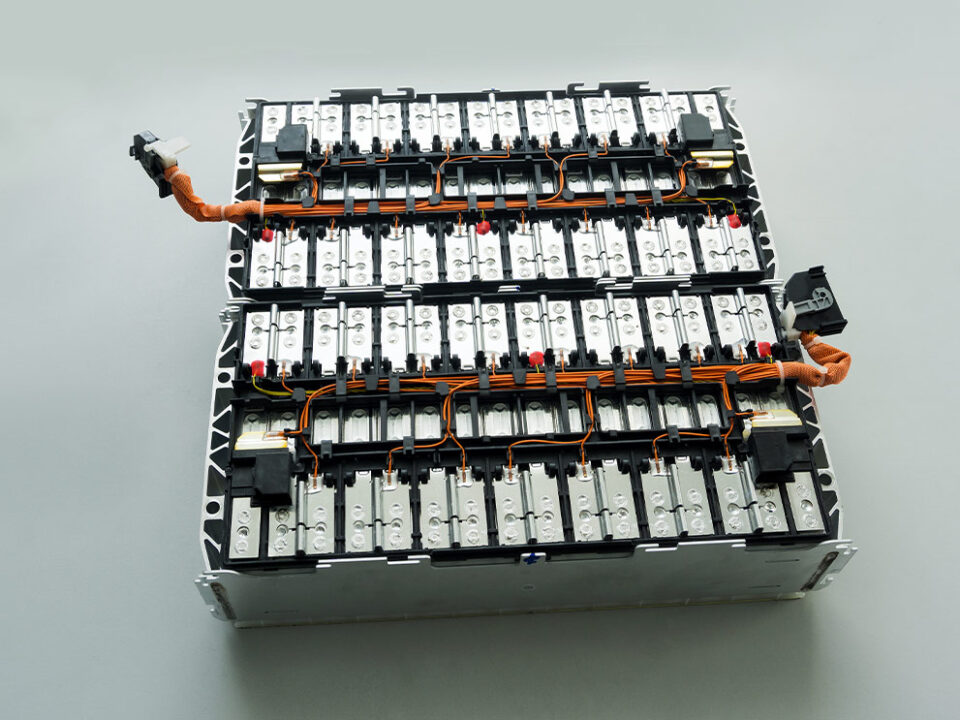

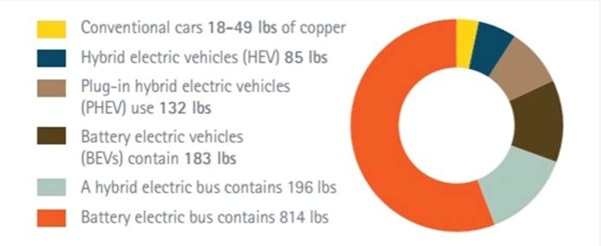

In electric vehicles (EVs), copper is a major component used in the electric motor, batteries, inverters, wiring and in charging stations. An EV contains about four times as much copper as a vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine (ICE).

The latest use for copper is in renewable energy technologies, particularly in photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines.

Electrification/ decarbonization challenge

Copper’s widespread use in construction wiring & piping, and electrical transmission lines, make it a key metal for civil infrastructure renewal.

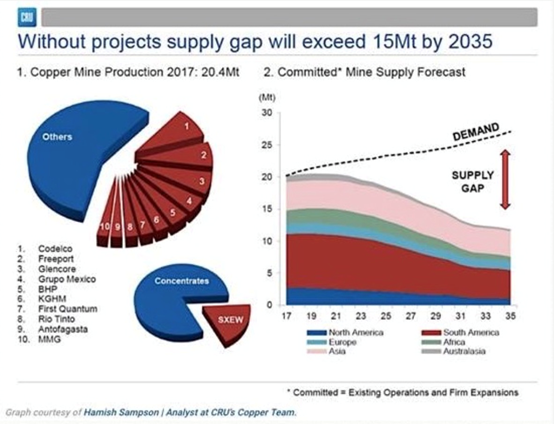

A report by Roskill forecasts total copper consumption will exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization, and electricity demand. Total world mine production in 2020 was only 20Mt.

The continued movement towards electric vehicles — including cars, trucks, trains, delivery vans and e-bikes, is a huge copper driver.

Before the covid-19 pandemic, we already had the beginnings of a copper shortage. But it wasn’t expected to hit until the early 2020s.

With covid-19, copper supply problems returned to the spotlight, following a flurry of temporary mine closures that reduced 2020 output in Chile, Peru and Mexico, which account for nearly half (45%) of global production.

China, Europe and the United States have all decided, and we agree with them, that the way forward, to pull their economies out of the pandemic, is to create massive infrastructure-spending programs, with a concentration on clean energy and transportation, and reducing carbon emissions.

These programs mean a lot more metals will need to be mined, including copper for electric vehicle wiring, renewable energy projects and 5G.

How much more copper?

According to BloombergNEF, there are currently about 7 million electric vehicles in the world today. By 2040, they estimate around 30% of the world’s passenger cars will be electric. To me that’s a conservative and reasonable number. It means 500 million EVs will be on the road in 20 years, out of a total vehicle fleet of 1.6 billion. If each EV contains 85 kg of copper, that is 42,500,000,000 kg, or 42,500,000 tonnes of copper, roughly twice the current volume of copper produced by all of the world’s copper mines.

Just so we’re clear — in 20 years, we need to double the amount of global copper production, just to meet the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles. We still need to cover all the new copper demanded by electrical, construction, power generation, renewable energy, 5G, etc., plus all the new copper demand from countries that currently can’t afford, but want, a Western lifestyle with all its metals-intensive modern products.

Undersupplied and over demanded

The big question is, will there be enough copper for future electrification needs, globally? Plus all the other modern-day uses of copper?

The short answer is no, not without a massive acceleration of copper production worldwide.

Global leaders have set strict decarbonization targets that require green-focused infrastructure built with copper. This, combined with a massive rise in government expenditures and years of underinvestment, has investment bank Goldman Sachs predicting that another commodity super-cycle is on the horizon.

BloombergNEF estimates that global copper demand in both the clean power and the clean transportation sectors will double in the next decades to almost 5Mt per year. Copper demand this year is expected to reach 24Mt, outstripping 2020 mine production by 4Mt.

Goldman analysts this week doubled down on copper, estimating that green projects would cost around $16 trillion to build, which is even more than the $10 trillion spent by China during the last super-cycle.

In a recent report titled ‘Copper is the new oil’, Goldman estimates prices will average $11,000 a tonne over the next 12 months, but by 2025 could hit $15,000/t ($6.80/lb).

The buoyant prediction, via Business Insider, is based on the fact that “Discussions of peak oil demand overlook the fact that without a surge in the use of copper and other key metals, the substitution of renewables for oil will not happen,” the bank said, noting that demand, subsequently, could increase by up to 900%, or 8.7 million tonnes, by 2030, or at the lower end, by 5.4Mt, a rise of almost 600%.

Projecting further out, the demand picture gets even more dramatic, and to us at AOTH, downright scary, because we know how dire the supply side is looking.

A recent research report from Jefferies Research LLC concluded: “The copper market is heading into a multiyear period of deficits and high demand from deployment of renewable energy and electric vehicles.”

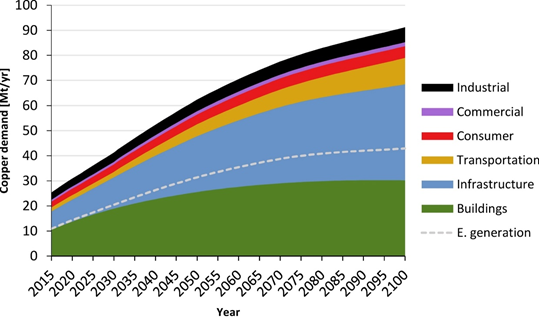

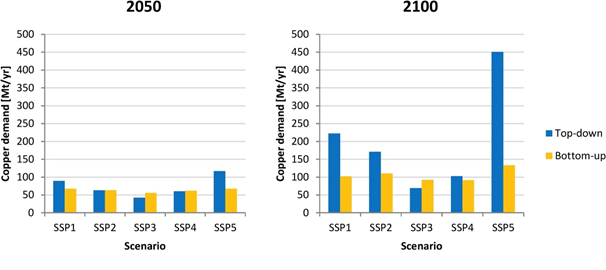

Graphs in a research report published on Science Direct indicate that by 2050, annual copper demand could reach close to 50 million tonnes in the “best case scenario” (see second chart below), and about 120Mt in the worse case. By 2100, demand could soar to about 70Mt best case, and a mind-boggling 450Mt worse case!

According to Goldman Sachs’s metals strategist, Nicholas Snowdon, copper is at the core of the green energy transition that will drive a capex boom over the next decade.

And while many have pointed to China as the main impetus behind global copper demand, during and post-pandemic, Snowdon says Goldman Sachs is forecasting demand growth in developed countries will be faster, close to 7% this year.

The world’s largest mining company, BHP, is also optimistic about copper going forward. The company’s president for the Americas, Ragnas Udd, told the CRU World Copper Conference in Chile this year that BHP has revised its EV penetration forecast upward, based on a favorable past 12 months.

It expects emissions reduction targets to more than double the demand for copper and quadruple the need for nickel over the next three decades.

The mega-miner is betting big on copper, having invested about US$11 billion in Chile alone, where it owns 100% of the Pampa Norte mine and has a 57.5% stake in Escondida, the world’s biggest copper mine.

All this positivity for copper may have some wondering how the red metal managed to do so well during a global pandemic. Since slumping to a 10-month low last March, spot copper has risen an astounding 94%.

CME Group has the answer. In a recent report explaining the economics of copper supply and demand, CME explains that covid-19 has affected sectors of the economic differently. Among the strongest are manufacturing and construction, both of which both consume a lot of finished copper. Housing starts and building permits, for example, at the start of 2021 were at their highest levels since before the financial crisis, spurred by low interest rates.

It’s the same story in China as in the United States. CME Group points out the strong relationship between copper prices and changes in the Li Keqiang Index (remember, Dr. Copper), which is a proxy for the Chinese manufacturing sector.

But we have a problem, Houston.

As demand for copper in manufactured goods and housing has surged, supply has not kept up.

As previously reported, global mined copper production will drop from the current 20Mt to below 12Mt by 2034, resulting in a supply shortfall of 15Mt. By then, over 200 copper mines are expected to run out of ore, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

A looming copper shortage has end users worried about their supply chains.

Speaking with Rick Rule at this year’s Sprott Natural Resource Symposium, mining magnate Robert Friedland said, “The copper price probably needs to double its current price for the average low-grade copper porphyry in Peru or in Chile to become viable.”

That, by the way, would mean copper hits 8 bucks a pound.

Billionaire Friedland, whose Ivanhoe Mines is developing the huge Kamoa-Kakula copper project in the DRC, also stated, at the CRU conference, that copper has become so crucial, finding enough of it has become “a national security issue”.

Bloomberg reports Friedland saying mining companies will have to be “real heroes” and governments will have to accept the industry if the world is to successfully transition to clean energy and transport.

Snowdon, of Goldman Sachs, points to the collapse in treatment and refining charges, that miners pay to smelters, as evidence of an undersupplied copper market. He predicts global mine supply will peak from 2024 onwards, and that market fundamentals will generate “a record long term supply gap by the end of the decade that has to be solved by investment in new mine capacity.”

Snowdon also points out that the current 8 million tonnes supply gap is close to double that of the last bull markets in the early 2000s and 2010s, agreeing with Friedland that, “This can only be resolved by higher prices stimulating investment in new supply.”

CME makes a couple of interesting observation re current supply problems. First, the group points out that temporary mine closures in Chile, the largest copper producing country, prevented 3.7% of global copper supply from getting to market in the H2 2020, amounting to a 1.5% annual fall in supply, versus 2019.

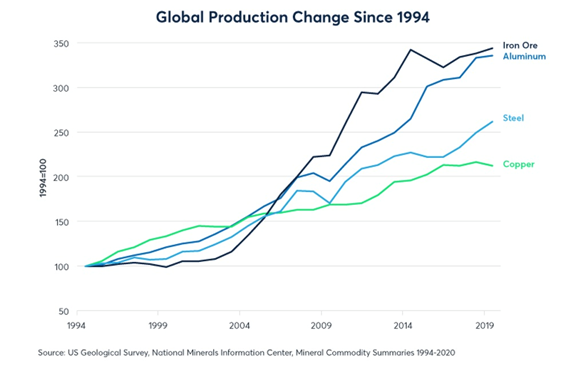

Second, there has been a much lower growth in copper supply over the past 25 years compared to say, aluminum and iron ore:

Since 1994, copper mining supply has doubled while the supplies of other metals have tripled.

Conclusion

Resource scarcity is one of the most serious challenges facing humanity in the next century, and copper is the poster child.

Another great challenge, climate change, is also inextricably linked with copper scarcity. Because without copper, the electrification of the global transportation system and the decarbonization of energy, cannot happen.

We’ve been saying this for years, only now, we are hearing an echo from other, more important voices.

“Discussions of peak oil demand overlook the fact that without a surge in the use of copper and other key metals, the substitution of renewables for oil will not happen,” Goldman Sachs just wrote in a report.

Robert Friedland, Mr. Copper himself, and a storied mine builder, has stated that copper should be a matter of national security. Who better to believe than the man whose company, Ivanhoe, is developing one of the world’s largest copper deposits, Kamoa in the DRC?

The existence of climate change, either human-caused, due to natural cycles or both, is no longer up for debate. To avoid ecological catastrophe, we must reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, clean up our environment, embrace renewable energies, and continue down the path of electrifying the global transportation system.

To do so we need to find more copper. A LOT more.

Ironic isn’t it, that the mineral which launched the Chalcolithic/ Copper Age, that transitioned civilization from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age, could also be the metal that determines whether modern society thrives in a new green economy, or struggles to survive, in a world still run on oil and gas.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.