8 Escondidas needed over the next eight years

2022.04.21

Speaking at the 2022 World Copper Conference in Santiago, Chile, CRU’s Erik Heimlich said that eight projects the size of Escondida are needed over the next eight years — a task that is more “possible” than “probable” given the scale of the developments required and the fact that about half of the projects in the pipeline are greenfield, i.e., new mines.

More like improbable. We’ve covered some of this ground before.

Chile’s Escondida is the world’s largest copper mine with an annual production capacity of 1.4 million tonnes. Escondida is so big, it can produce more copper than the second and third largest mines combined (Chile’s Collahuasi @ 610,000 tonnes + Mexico’s Buenavista del Cobre @ 525,000t).

Mining Intelligence Data ranks Escondida the world’s biggest mine (of all commodities), churning out a whopping 360,000 tonnes per day on average. Based on production for the first three quarters of 2021, Escondida was on track to mine 130.78 million tonnes of copper, silver and gold last year, compared to a projected 104.65Mt at Collahuasi.

According to Mining Data Online, as of June 30, 2021, Escondida had proven and probable reserves of 6.969 billion tonnes, at an average grade, between the three ore types (heap leach, sulfide and oxide) of 0.53% Cu.

The reason for citing these statistics is to show how much more copper is required for the mining industry to avoid a supply crisis that is all but guaranteed by the end of this decade.

In March, the head of base metals supply at CRU, a leading authority on copper, said the global copper industry needs to spend more than $100 billion to build mines able to close a projected annual deficit of 4.5 million tonnes by 2030. The next decade, the supply gap widens to 6Mt.

Other analysts think the supply crunch will come much sooner.

S&P Global Market Intelligence predicts that due to a shortage of projects, copper supply will lag demand starting as early as 2025, with global mine production dropping from last year’s 21Mt to roughly 15.9Mt in 2030.

Diminishing supply from currently operating mines, combined with the projected increase in demand for copper concentrate over 2021-2030, will result in a 3.85Mt production shortfall in 2025, S&P Global estimates.

According to CRU there are 12,145 kt of uncommitted possible copper production between now and 2031:

- probable (4,000 kt)

- possible (6,600 kt)

- speculative (1,500 kt)

From CRU analysis of projects in 2015 and their 2020 status:

- 80% of all committed projects in 2015 had made it into production by 2020.

- 47% of all probable projects in 2015 had become committed by 2020 and 13% of all probable projects in 2015 were operating by 2020.

- 55% of all possible projects in 2015 remained possible by 2020, but 26% had been canceled; only 6% of possible projects had become committed by 2020.

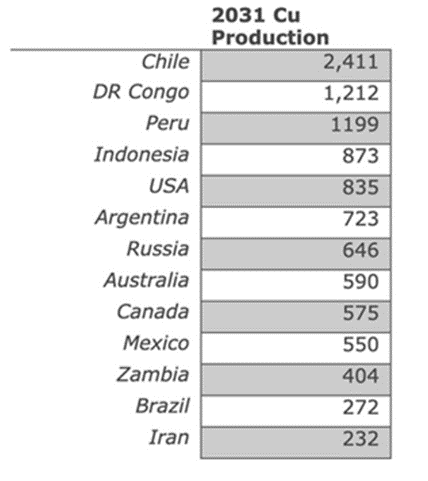

In the table below, CRU provided us with a breakdown of where future (2031) production is located. Notice that Chile tops the list followed by the DRC, Peru and Indonesia.

We also know that new supply is mostly concentrated in just five mines — Escondida, Spence, Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and Kamoa-Kakula. Three of these mines are in Chile, one is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the fifth mine is in Panama.

At Cobre Panana, nearly half of the 300,000 tonnes per year (tpy) production goes to Korea. Under a 15-year offtake agreement, Canadian miner First Quantum Minerals will ship 122,000 tpy of copper concentrates per year from Cobre Panama to South Korean copper smelter LS Nikko.

The Kamoa-Kakula copper project is a joint venture between Ivanhoe Mines (39.6%), Zijin Mining Group (39.6%), Crystal River Global Limited (0.8%) and the DRC government. Kakula reached commercial production on May 25, 2021, and while output is currently set for 200,000 tpy in Phase 1, a second phase would add 200,000 tpy and peak production would exceed 800,000 tpy.

Last June Ivanhoe signed two offtake deals, one with a subsidiary of its partner firm, China’s Zijin Mining; the other with Chinese commodities trader CITIC Metal, to sell each 50% of the copper production from Kakula — the first of two mines involved in the joint venture. In other words, 100% of Kamoa-Kakula’s Phase 1 production goes to China.

That leaves three mines in Chile — Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca’s “QB2” expansion. In 2016 BHP, the majority owner of Chile’s Escondida, the largest copper mine in the world, committed to spend just under $200 million to expand its Los Colorados concentrator. The expansion would help offset declining ore grades and add incremental copper production to reach an average 1.2 million tonnes a year over the next decade. BHP owns a 57.5% share in Escondida, Rio Tinto owns 30%, and the remaining 12.5% is owned by JECO Corp and JECO2 Ltd.

JECO is a Japanese joint venture between Mitsubishi Nippon Mining & Metals and Mitsubishi Materials Corp. It is not immediately clear whether any of Escondida’s production is bought by JECO Corp.

BHP said in 2021 that the expansion of its Spence mine is expected to be completed within one year. Once the operation hits full production, it would produce 300,000 tpy until at least 2026. Spence ownership is split 50-50 between BHP and Santiago-based Minera Spence SA.

Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 project is expected to produce 316,000 tpy of copper equivalent for the first five years of its 28-year mine life. In 2019 the Canadian company closed a $1.2 billion transaction whereby Tokyo-based Sumitomo Metal Mining and Sumitomo Corp will, through an $800 million and a $400 million contribution, acquire a 30% interest in project owner Compañia Minera Teck Quebrada Blanca S.A. (“QBSA”). Like Escondida, it is unclear whether the two Japanese companies will take a portion of QB2’s production, or whether they will simply share in the profits.

Summing up, our analysis shows that in two of the five mines where new copper supply is concentrated, there are offtake agreements in place with non-Western buyers. In the case of Kamoa-Kaukula, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project. Nearly half of Cobre Panama’s annual production goes to a Korean smelter under a 2017 offtake agreement.

Now, we can’t obviously say, because it’s too early, what percentage of CRU’s expected 12,145 kt of production in 2031 will actually make its way into global copper supply.

However it is reasonable to expect that some percentage will be set aside for offtake agreements and that the most likely recipient of those offtakes is China, which currently consumes half of the world’s copper.

Remember, only 6% of possible projects in 2015 had become committed by 2020 and 26% had been canceled. Of probable projects in 2015, less than half (47%) had become committed by 2020, and only 13% were operational.

Despite the best laid plans copper mines never seem to reach their yearly production milestones. Globally we must factor in between an 800,000-tonne and 1.2 million-tonne annual aggregate loss, due to any number of factors beyond their control. This includes mine strikes, port strikes, work stoppages due to earthquakes, floods, or the latest output interruption, covid-19.

Future projects in doubt

In the latest annual survey of mining companies released by think-tank the Fraser Institute, Canada is seen to be not doing enough to make the country an attractive jurisdiction for mining investment.

“Overall, senior mining executives continue to cite the uncertainty around protected areas, disputed land claims, and environmental regulations as major areas of concern for Canadian provinces and territories,” said Elmira Aliakbari, director of the Fraser Institute’s Centre for Natural Resource Studies and co-author of the study.

“Policymakers in every province and territory should understand that mineral deposits alone are not enough to attract investment,” Aliakbari said.

Bill C-69 is an example of legislation passed by a government that has the ear of special interests. The new legislation broadens the scope of the assessment process and adds more consultation with the public and particularly indigenous groups.

Such anti-mining legislation can present a significant obstacle to companies trying to move a project forward to production, and in the worst of cases, drags the process out so many years that the economics no longer work and the mine is shelved.

This often happens in North America, where it can take up to 20 years to move a project from discovery to commercial production. A preliminary economic assessment done in year 3 is of little use if the minerals aren’t produced until year 20.

An earlier Fraser Institute report found that Canadian mining jurisdictions lagged their international competitors for increases in the time for permit approval, transparency and confidence that permits will be granted.

State-side, the Biden administration has come out against domestic mining through a number of anti-extractive industry decisions, while it supports cleaner EV manufacturing and auto-assembly.

Instead of building a “mine to EV” supply chain, Biden and his Democrats want to skip the mining and go straight to the cleaner, manufacturing-intensive electric vehicle-building, that will supposedly bring plenty of jobs.

A Reuters story claims the United States has enough reserves of lithium, copper and other metals to build millions of its own vehicles, but opposition to new mines may force the country to rely on imports that could delay efforts to electrify its roughly 275 million cars and trucks.

“Increasing technical complexity and approval delays could lead to a dearth of shovel-ready projects in 2025-30,” Bloomberg Intelligence analysts Grant Sporre and Andrew Cosgrove wrote in a recent report.

We can easily see this in the table below by Mining Intelligence. Note the fourth column, “Development Status”. Only three projects out of 10 have reached the feasibility stage, the rest are in quite early phases of development. They will take at least a decade to become mines, at which point the copper market will already be in deficit. One of them is in serious doubt, after a congressional committee voted to block Rio Tinto building its Resolution copper mine in Arizona.

A 2021 report by Goehring & Rozencwajg Associates (G&R) found that stagnating supply is a key factor pushing “copper prices far higher than anyone expected.”

According to G&R, the number of new world-class discoveries coming online this decade “will decline substantially and depletion problems at existing mines will accelerate.”

Also, geological constraints surrounding copper porphyry deposits, a subject few industry analysts let alone investors understand, will contribute to the problems, the report said.

By 2015, the industry’s head grade was already 30% lower than in 2001, and the capital cost per tonne of annual production had surged four-fold during that time — both classic signs of depletion.

According to the Goehring & Rozencwajg model, the industry is “approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades,” and brownfield expansions are no longer a viable solution.

“If this is correct, then we are rapidly approaching the point where reserves cannot be grown at all,” the report concluded.

It also shines a light on the importance of making new discoveries in establishing a sustainable copper supply chain.

Over the past 10 years, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically, with tonnage from new discoveries falling by 80% since 2010.

Demand continues to surge

Of course, the copper industry’s supply issues must be compared to what is happening with demand.

A report by Roskill forecasts total copper consumption will exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization and electricity demand. Total world mine production in 2021 was only 21Mt.

The continued movement towards electric vehicles is a huge copper driver. EVs use about four times as much copper as regular internal combustion engine vehicles.

The latest use for copper is in EVs and their charging stations, renewable energy, particularly in photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines. The base metal is also a key component of the global 5G buildout. Even though 5G is wireless, its deployment involves a lot more fiber and copper cable to connect equipment located within a building.

Pent-up and new demand for infrastructure and manufactured goods is expected to boost the prices of industrial metals, including copper.

While the United States in November passed a trillion-dollar infrastructure package that includes money for roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, China is looking to outspend it by a large margin.

At Beijing’s behest, local governments have reportedly drawn up lists of thousands of “major projects,” which they’re being put under intense pressure to see through. Planned investment this year amounts to at least 14.8 trillion yuan ($2.3 trillion), according to a Bloomberg analysis. That’s more than double the new spending in the infrastructure package the US Congress approved last year, which totals $1.1 trillion spread over five years.

Notably, the composition of the stimulus spending will be less on infrastructure than manufacturing, including factories, industrial parks and technology incubators. The construction push is part of the central government’s plan to meet its targeted 5.5% growth rate this year.

Price targets revised upward

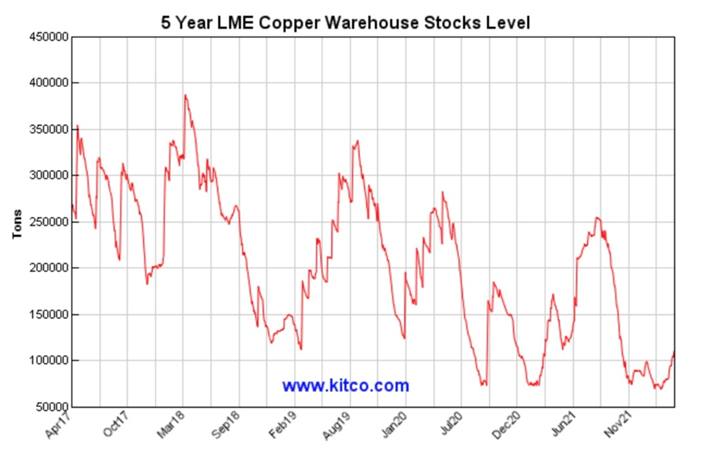

Goldman Sachs recently warned that copper is “sleepwalking towards a stockout” similar to last year, when inventories of the red metal plunged to their lowest since 1974.

In its report, Goldman points to “an extreme fundamental turn” for copper, whose stocks on metal exchanges for the first time in a decade declined through March instead of rising.

Analysts at Goldman were quoted saying the bank believes “higher prices are an inevitability,” needed to stimulate more scrap copper supply and to accelerate demand destruction to balance the market.

The analysts reportedly doubled the deficit of refined metal expected for this year from previous estimates to 374,000 tonnes and also increased substantially the shortfalls projected over the next two years.

Goldman upped its three, six and 12-month price targets, and forecasts copper climbing to 13,000 a tonne ($5.89/lb) within a year’s time. The analysts see a new all-time high for the copper price by mid-year.

This week, despite a resurgence of covid-19 crimping demand in China, where authorities have locked down over 20 cities including 26 million people in Shanghai, copper shot up to $4.82 per pound, after the country’s largest copper producer, Yunnan Tin Co., halted production at its mining unit to comply with local government virus restrictions.

While the copper market hasn’t yet reached the 4.5Mt shortfall CRU predicts by 2030, nor the 3.8Mt gap by 2025 forecasted by S&P Global — either way, a structural supply deficit the industry will find difficult to avoid, given all the challenges described above — we can already see warnings flashing with respect to the depleted inventories of copper in London Metal Exchange warehouses.

Inventory red flags

In February copper stocks worldwide fell to just over 200,000 tonnes, barely enough to cover three days of global consumption.

Reuters said last week that inventories across London Metal Exchange warehouses of copper, lead, nickel, zinc and tin haven’t been this low for 20 years, with the total amount of registered metal in the LME’s global warehouse network falling below 1 million tonnes in March.

The result is higher prices and increased volatility.

There are mainly three reasons for the low volume of metal being warehoused: pandemic lockdowns, logistical disruptions and smelter cutbacks in Europe.

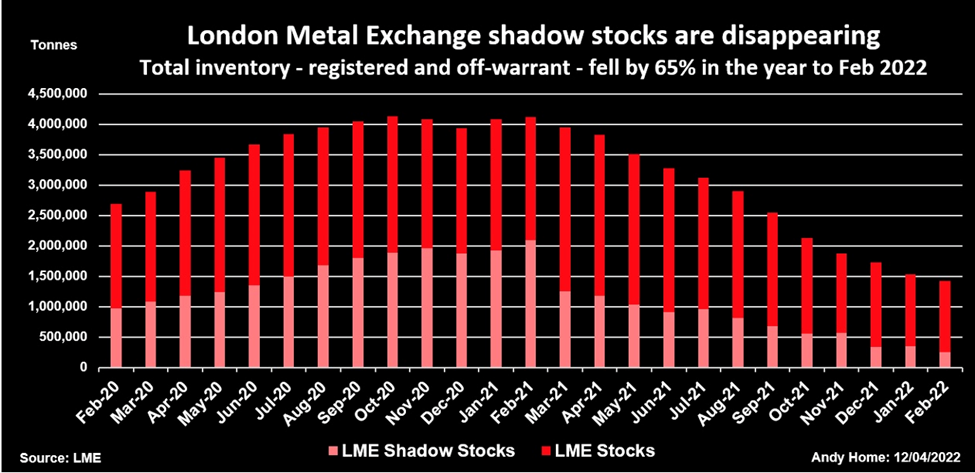

An even bigger draw-down is occurring within LME shadow inventories, referring to metal that is stored off-market but is under a warehousing contract allowing for exchange delivery.

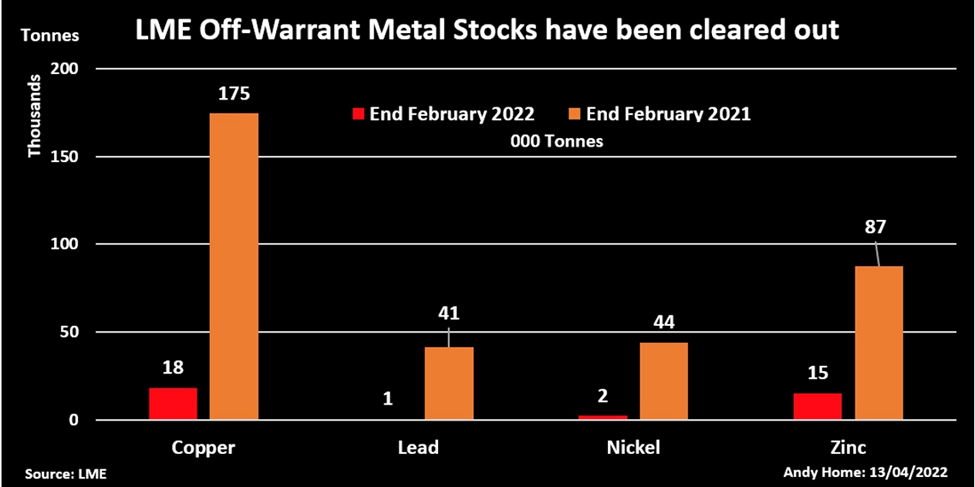

These “off-warrant” stocks amounted to 256,000 tonnes at the end of February, down 88% on the 2Mt sitting in shadow inventories a year earlier. As shown in the chart below, total inventory, i.e., registered and off-warrant, fell by 65% in the year to February 2022.

According to Reuters metals columnist Andy Home, The evaporation of this buffer stock means any call on metal from the market of last resort must be made on the dwindling volume of registered inventory.

It helps explain why the 145-year-old dame of industrial metals trading has been swamped by ever greater waves of market turbulence, culminating in the March suspension of the nickel contract.

Off-warrant copper inventory collapsed from 175,000t in February 2021 to 18,352t at the end of February this year.

It’s not only copper that is vanishing from the LME’s shadow stocks.

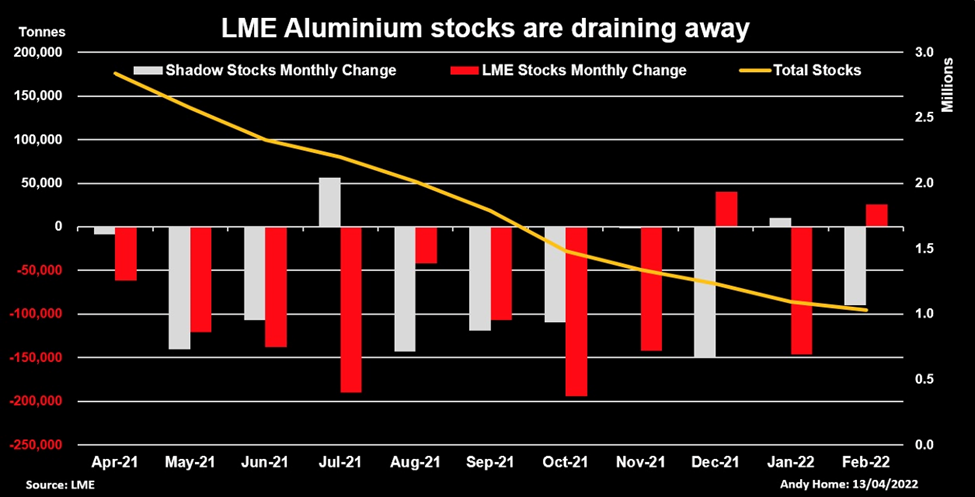

Off-warrant aluminum stocks were at 1.74Mt in February 2021 but a year later they had shrunk to just 218,000t. Home notes the fact that both shadow and registered aluminum stocks have been falling in tandem, is a sign of an under-supplied market.

Shadow nickel stocks are also being rapidly depleted, crashing from 44,000 tonnes to 2,428t in the same period. Same with lead and zinc, with off-warrant zinc stocks plunging from 87,000 tonnes a year ago to 15,261t in February.

With shadow zinc inventories almost fully depleted, zinc buyers must now turn to zinc sitting on LME warrant. That explains why LME on-warrant zinc stocks have tightened considerably (falling by 60,000 tonnes since the start of April) and why the LME’s three-month zinc price recently blew past $4,500 a tonne ($2.04/lb).

As of April 13, zinc inventories in LME-registered warehouses had fallen to their lowest since June 2020 at 115,600 tonnes.

Chile risks losing its copper crown

Some of the strongest evidence of the growing copper crisis is found in Chile, the world’s biggest producer of the metal.

The nation’s copper output tumbled 7.5% in January compared to the same month in 2021, to 425,700 tonnes, the lowest in 11 years, after weak performances from some of its biggest mines.

Escondida, the world’s largest deposit, saw its production fall 4.4% year-on-year, while the Collahuasi mine recorded a 10% drop.

Arguably, this is a sign of what’s to come in the copper market and a harbinger of declining mine production. Chile came into 2022 having experienced a 2% drop in its 2021 copper output.

Among the reasons for the sharp drop, cited by the Chilean Copper Commission (Cochilco), were lower ore quality and water scarcity.

Copper grades have declined about 25% in Chile over the last decade, bringing less ore to market.

Making matters worse, after more than a decade of drought, freshwater supplies are becoming a big problem in Chile. Copper mines there require lots of water to process sulfide ores, and the lower the grade, the more water must be used.

Since major copper miners are increasingly turning to low-grade sulfide deposits to beef up their production, their water consumption is expected to jump up to 20.9 cubic meters per second (about half an average backyard swimming pool). Water scarcity in effect hinders their ability to produce.

BMO estimates the country’s 2022 copper production has slowed to a pace where it could be lower than 2004, when mine output was slightly over 5.4 million tonnes, equivalent to 37% of the world’s production.

“Following the steady ramp-up in the 1990s and early 2000s, output levels have stagnated, with the projections of 6 million tonnes per year-plus of output never coming to pass,” the bank’s managing director of commodities research, Colin Hamilton wrote.

Another event that has yet to come into play is Chile’s proposed nationalization of its copper (and lithium) industry. While the change to the constitution still faces hurdles, the idea has made miners nervous about their Chilean operations. A new mining royalty bill would see an “ad valorem” tax corresponding to 1% of annual copper product sales, applied to firms producing under 200,000 tonnes per year. Mines producing under 50,000t would be exempt. An amended version of the legislation was passed by the Chilean Senate in January.

Similar fears exist in neighboring Peru, the second-largest copper producer. There, the government wants to raise mining taxes by 3 to 4 percentage points, an amount that Peru’s mining chamber says would put more than $50 billion in future investments at risk. On April 20th the following article was posted on mining.com, Fifth of Peru copper mining goes offline with more shutdowns likely

Conclusion

One of the problems with copper is it is difficult to find in large enough amounts close to surface, where it’s economical to extract. It also takes many years to bring a copper deposit into production, especially in places like the United States and Canada where miners face strict permitting regulations that can cause delays. According to Bloomberg Intelligence, the average lead time from first discovery to first metal has increased by four years from previous cycles, to almost 14 years. In fact it can take up to 20 years to build a mine in North America.

In a previous article we showed that four out of the five major copper projects in the pipeline right now either have offtake agreements in place with non-Western countries (South Korea and China), or the mines are partially owned by Japanese companies that have a say in where some of the mined copper is destined. (i.e. Japan).

We make a clear distinction between global copper supply and the global copper market. Mined copper that is locked up by offtake agreements should not rightly be lumped in with global supply, because it will never reach the United States, Canada or Europe. Instead, this copper will go straight to smelters in China for use in Chinese industry, to South Korean smelters for South Korean industry, and to Japanese smelters for Japanese industry. We can hardly call this situation Western security of supply, when most of the raw copper material (cathodes or concentrate) is going to China, South Korea and Japan, who then turn around and sell more expensive copper end products to North America and Europe.

Analysts say we won’t run out of copper until 2025 at the earliest but the signals from warehouse inventories are worrisome to say the least.

“Off-warrant” stocks amounted to 256,000 tonnes at the end of February, down 88% on the 2Mt sitting in shadow inventories a year earlier.

Total registered metal in the LME’s global warehouse network fell below 1 million tonnes in March, resulting in higher pricing and increased volatility for a number of industrial metals, including copper, nickel, aluminum and zinc.

Off-warrant copper inventory collapsed from 175,000t in February 2021 to 18,352t at the end of February this year.

A 2021 report by Goehring & Rozencwajg Associates (G&R) found that the number of new world-class discoveries coming online this decade “will decline substantially and depletion problems at existing mines will accelerate.”

We already see the latter happening in Chile, the top copper-producing country, where copper output fell 7.5% in January to 425,700 tonnes, the lowest in 11 years, after weak performances from some of its biggest mines.

Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research for Goldman Sachs, has declared copper “the new oil”, noting it’s absolutely indispensable in global decarbonization strategies with copper shortages already being felt.

The industry is running out of copper at precisely the wrong time, as demand is accelerating rapidly not only for traditional uses, i.e. construction, transportation and telecommunications, but for the green economy which includes vehicle electrification and renewable energy.

On top of depletion, lower grades, high-grading, and a dearth of new copper discoveries, there are other issues making it difficult to add to supply.

One problem is the need to go further afield and dig deeper to find copper at the grades needed to economically produce copper products for end users. This usually means riskier jurisdictions that are often ruled by shaky governments with an itchy trigger finger on the resource nationalism button. All the low-hanging copper “fruit” has been picked. Combine that with production problems and you have all the makings of a structural supply shortage.

According to CRU, the copper industry needs to spend upwards of $100 billion to erase what it estimates to be a 4.5Mt deficit by 2030. We are talking about adding one mine size of Escondida a year, every year for the next eight years!

While such a feat is difficult, if not impossible to achieve, finding the right investments in projects leading to copper discoveries will help to close the supply gap.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.