The link between commodities and inflation – Richard Mills

2023.03.08

Has anybody noticed there is something strange going on in commodities? Whether we are talking about metals, energy, lumber, livestock or crops, commodities normally move in the opposite direction as the US dollar.

The reason for this is self-evident. A weak dollar usually means stronger commodities prices. Because the USD is the reserve currency and commodities are traded in dollars, the value of the dollar is of crucial importance in determining the value of the commodity in question. Take the case of a low dollar. When the dollar drops it takes less of another currency to buy dollars needed to purchase the commodity, so the demand for that commodity will increase. The inverse happens when the dollar strengthens.

The US dollar is currently robust, it’s been gaining since the beginning of February after falling steeply for three months (the US dollar index DXY having reached a 21-year high of 114 on Sept. 26, 2022) due to continued tight monetary policy from central banks around the world, which continue to fight inflation that in some countries is raging at the highest level in 40 years, by raising interest rates. Government bond yields are tracing higher, in lock step.

Yet what is happening to commodities? The Bloomberg Commodity Index, while slipping from a 10-year high in May, 2022 of 133, is still the highest since 2014, @ 107, as of this writing.

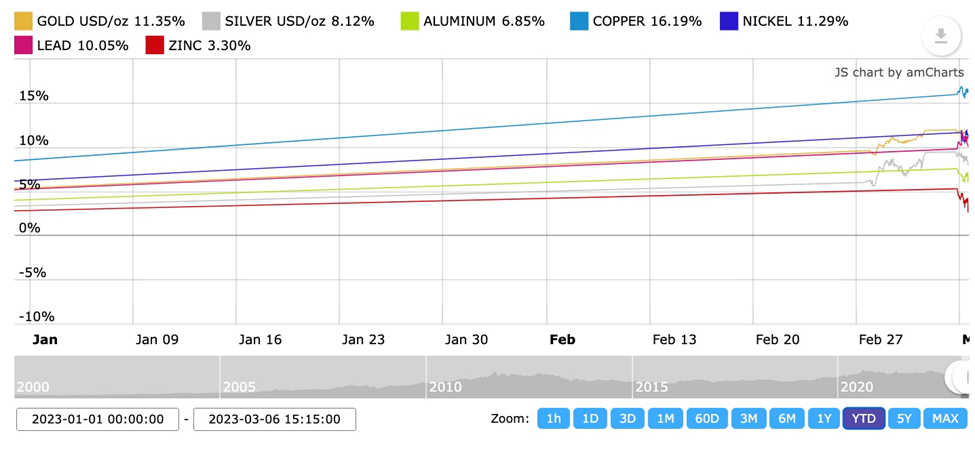

Gold, silver and industrial metals have done well so far this year, as the chart below shows. How can gold be at $1,850 when the dollar is surging?

The answer, I believe, boils down to the demand for commodities being kept elevated by governments, who are fueling inflation through hundreds of billions, in some cases trillions, of new spending, even as central banks tackle rising prices by hiking interest rates. The two are working at cross-purposes, and the loser is the consumer, being forced to pay both higher prices, and higher interest on loans/ mortgages.

While a recession in 2023 will obviously slow the demand for metals and other raw materials, commodity prices are expected to remain high, in everything from oil to copper to wheat.

The Washington Post published an op-ed by Javier Blas, former Bloomberg News reporter and Financial Times commodities editor, stating that The global economy is hard-pressed to satisfy its own commodity needs. Despite the past year of sky-high prices, the natural resources industry isn’t rushing to invest in more capacity to alleviate supply shortages. Without an investment boom, the only way to rebalance the market in the new year is through lowering demand.

We’ve heard this argument numerous times. To “kill demand” central banks hike interest rates, thereby incentivizing consumers to save, and discouraging homeowners and businesses from borrowing. But this tactic does nothing to alleviate supply interruptions caused, for example, by the war in Ukraine, or droughts’ impact on crops.

Nor does it address mine supply constraints. Blas rightly points out that, unless mining companies build more mines, which would increase supply, the only way to bring down commodity prices is by influencing them on the demand side, through interest rate increases. Yet, the impact will be limited, because even if macroeconomic forces ease some commodity cost pressures, microeconomic factors, such as low inventories and limited spare capacity, will keep prices higher than during past recessions.

Take a moment to digest what is being said here. Even if tight monetary policy works in suppressing inflation to some degree, in fact, even if it drive the world economy into a recession due to still-high inflation, that won’t be enough to cancel out prices being ratcheted higher due to tight supply conditions.

Governments vs central banks

I believe there is a fundamental misunderstanding right now as to what is causing inflation. I’ve heard commentators blame a shortage of workers/ higher wages, supply chains, pent-up demand, covid-19 stimulus payments, energy prices, and even the drive to increase corporate profits. Imo they are all missing the point.

While central banks around the world try to defeat inflation by hiking interest rates, thereby crimping demand for goods & services, governments are adding to it with prodigious new spending.

Remember, economies with fiat currencies rely on money-printing, and borrowing, to pay for their expenses not covered by the amount of taxes they take in.

The United States leads the way in this fiscal free-for-all, followed by Europe. The Biden administration’s $5.8 trillion federal budget will add nearly $15 trillion in new debt over the next decade, with annual budget deficits of at least a trillion per year.

Globally, governments are being forced to spend more to deal with an energy and food crisis that is squeezing consumers’ pocketbooks, and they will almost certainly be called upon again, if the world economy enters a recession as it is expected to this year.

The problem is, this policy of government largesse runs counter to central banks, who are raising interest rates to quell demand for goods and services, and thereby slow inflation.

It’s a tug of war between monetary authorities, who see inflation as something needing to be stamped out through higher rates, and governments, who are expected help out citizens with cost-of-living increases, by spending more or taxing less.

We’ve written about this discrepancy before — governments vs central banks — but throw in the rising dollar, and you have something new.

Commodities as leading inflation indicator

Don’t believe me when I say that commodities have a substantial impact on inflation? In a recent report, the Bank of International Settlements said virtually the same thing, noting that the combination of a stronger US dollar and higher commodity prices, which is a departure from a historical trend, increases the risk of global stagflation. Stagflation is what happens when high inflation is combined with low economic growth.

“Commodity price rises tend to stoke inflation,” the report said, with higher commodity prices leading to increases in the cost of living and production. “Inflation driven by higher commodity prices could prompt a monetary policy response that dampens the real economy,” BIS said — parroting what we at AOTH have been saying for years.

Economists are finally realizing that commodity prices influence the prices of manufactured goods, whether the end users are consumers, car companies, construction firms, or food suppliers. The monetary policy response, of course, is higher interest rates.

Take oil, for example. Past increases in oil prices have been a strong indicator for inflation, given that oil is such a major input in the world economy. Try making plastics without petroleum, or fertilizer without natural gas.

According to Investopedia, commodity prices are a leading indicator of inflation through two basic channels: commodities respond quickly to economic shocks such as increases in demand — for example the level of increased demand for goods and services that followed the end of pandemic restrictions; and systemic shocks such as hurricanes or other natural disasters:

“By the time it reaches consumers, overall prices would have increased, and inflation would be realized.”

The Bank of Canada last May emphasized the importance of commodities in the Canadian economy, stating that the prices of energy, lumber and agriculture doubled in the past two years, primarily because the economic upheaval caused by the pandemic, alongside supply bottlenecks and production slowdowns, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. “As a result, Canadians are facing much higher prices for everyday goods like gas and groceries. Inflation is at 6.7% [now 5.9%] — a three-decade high.”

In discussing market trends and the 2023 investing outlook for commodities, Rob Haworth, investment strategy director at US Bank, wrote in a column that Commodity prices played a major role in inflation’s surge that began in 2021, and also contributed to a pullback from peak inflation levels late in 2022.

Haworth noted commodities represent close to 40% of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), with energy accounting for 7.5% and food representing close to 14%.

His colleague Tom Hainlin pointed out the risks of the Russo-Ukraine war relative to food supplies — “Africa remains heavily reliant on food shipped from Russia and Ukraine”.

Both strategists are bullish on energy going forward, with Haworth saying that energy demands are likely to hold up over the long term, even with increased focus on carbon emission reductions. “OPEC and others did not put much new investment into infrastructure that could boost production,” says Haworth. “Five-year rolling inventory levels are low, so if demand for oil picks up, prices are likely to rise as well.”

Hainlin said the current environment differs from the usual trend in the energy industry, of producers expanding capacity when prices go up, before they reach a point of overcapacity and prices drop. “This typically leads to a boom-and-bust cycle. But instead, oil producers demonstrated significant capital discipline.” The column says that may keep production levels down, which could support elevated oil prices.

Hainlin adds that if China can resume normal business activity, “that would be a tailwind to industrial metals, such as copper.”

Global infrastructure & clean energy spend

Digging deeper into our thesis, of government spending leading to higher commodity prices, being the primary inflation driver.

Many countries need to reduce their so-called “infrastructure deficits”, the gap being the difference between what is being spent on infrastructure and what is required. Basic infrastructure such as roads, bridges, water & sewer systems, has been poorly maintained, and requires hefty investments to repair or replace.

In 2021, President Biden passed a $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill, that aims to put $550 billion in new funds into transportation, broadband and utilities. The legislation earmarks $110 billion for roads, bridges and other major projects, along with $66 billion in freight and passenger rail, including potential upgrades to Amtrak. $39 billion will be funneled into public transit.

Investment in US infrastructure becomes even more crucial in light of increased global competition, and the amount other world powers have pledged to spend.

China already spends more each year on infrastructure than North America and Western Europe combined.

The world’s biggest commodities consumer committed to spend US$2.3 trillion in 2022 alone, on major infrastructure projects. They are part of Beijing’s Five-Year Plan that calls for developing “core technologies” including high-speed rail, power infrastructure and new energy.

Last year the amount of money invested in decarbonizing the world’s energy system surpassed a trillion dollars for the first time. 2022 was also the first year that the $1.1 trillion which poured into the energy transition matched the $1.1T global investment in fossil fuels.

Another record: the year-on-year increase of >$250 billion (2022 vs 2021) was the largest ever jump, according to a recent Bloomberg story. While there has been $6.7 trillion invested in the energy transition since 2004, the article points out that it took eight years to reach the first trillion, less than four years to reach the next trillion, and under one more year to reach the latest trillion. In other words, the investment in green energy is accelerating dramatically.

Green energy investment matches fossil fuels for the first time

The International Energy Agency (IEA) wrote in December that global government spending on clean energy since March, 2022 increased by over USD$500 billion, bringing the total amount spent since the start of the pandemic to $1.2 trillion.

Furthermore, this government spending is set to mobilize substantial flows of private investment, which would raise global clean energy by another 50% to over $2 trillion annually by 2030, the IEA states.

The organization notes the largest increase in clean energy investment from December, 2021 to December, 2022, came from the US Inflation Reduction Act and by measures enacted by several European countries.

The majority of the funding in the $369 billion IRA takes the form of tax credits meant to incentivize private investment in clean energy, such as wind and solar, and in theory, boost US production of renewables as the nation pursues ambitious carbon emissions goals and a supply chain less dependent on China. (ABC News, Jan. 29, 2023)

Governments around the world have spent a further $630 billion to protect households and businesses from rising energy bills from the fall of 2021 to December, 2022, the IEA states.

Gold and silver

There is a certain logic behind the concept of higher prices for industrial metals feeding into inflation. Iron ore, copper, aluminum, zinc and nickel, are all heavily used in construction projects. Battery metals lithium, nickel, aluminium, graphite and manganese are needed for vehicle electrification.

But what about silver and gold? The precious metals are unique in that both are purchased for investment purposes, gold more than silver. Silver is about 60% industrial and 40% monetary.

Investors often turn to precious metals during periods of economic or political turmoil, and especially when inflation is high. That’s because, unlike fiat currencies, gold and silver do not lose value to currency debasement; they are considered hedges against inflation.

Like with commodities and the dollar moving together, rather than inversely, gold and silver’s movement appears to be knocking historical trends. For the sake of simplicity, let’s stick with gold.

There are two factors at play. The first, and easiest to explain, is why gold isn’t doing better during this period of high inflation. The economy is inflating at the same time as central bank banks are raising interest rates. Gold’s price appreciation is therefore limited by higher rates and bond yields. Why invest in gold, with offers neither interest nor a dividend, when you can get a decent return on a government bond, or just by stuffing a bunch of cash into a savings account that nowadays pays around 3%?

The second factor is a big more complicated. Why is gold trading at $1,850, when the US dollar index is at 104? Central bank buying is one reason why gold has held its own over the past few months.

Central bank gold demand has reportedly seen a continuation from 2022’s record year of purchases, with CBs adding 31 tonnes to global gold reserves in January, the World Council said last week.

The largest buyer was the Central Bank of Turkey, followed by the People’s Bank of China and Kazakhstan’s national bank.

January’s central bank gold haul was 16% higher than December. The WGC sees the trend continuing throughout this year.

“We see little reason to doubt that central banks will remain positive towards gold and continue to be net purchasers in 2023,” the report said. “The healthy January data we have so far gives us little reason, at this time at least, to deviate from this outlook.”

Last year, central banks purchased 1,136 tonnes — the most on record and a more than 150% increase from 2021. (Kitco News, March 2, 2023)

Gold would undoubtedly be higher if investors were treating it as a monetary metal — one to go to as a safe haven. Again we find perplexity in the fact that, with all that is going on in the world — four hot spots in 2023 are the war in Ukraine, Iran protests, US-China trade relations, and North Korea — there appears to be little safe-haven demand for gold.

Instead, investors are piling into the tried and true haven, US Treasuries. As mentioned, government bond yields are up, the result of higher interest rates, and that is attracting a lot of foreign bondholders. According to the US Treasury Department, foreign residents increased their holdings of US Treasury bills by $44.1 billion in December.

That leaves only one other explanation for gold and silver strong performance amid a higher dollar, and that is the “float all boats” theory. I believe the general surge in commodity prices is also lifting up gold and silver, like a rising tide, even though they aren’t directly connected to electrification & decarbonization government funding, or infrastructure investments.

If we do end up with a recession, or if one of four global hotspots (Ukraine, Iran, North Korea, US-China trade relations) heats up, look for gold to gain further on strengthened safe-haven demand.

Conclusion

The Bank of International Settlements maintains there is “a lasting positive correlation between commodity prices and the dollar exchange rate.” BIS also said in its recent report that, “Central banks have been very clear about the priority of getting the job done and of being cautious about declaring victory too early,” referring to a volte-face with respect to interest rate increases meant to tackle inflation.

As long as the Fed and global governments continue on their current paths, with the Fed maintaining high interest rates, and governments continuing to invest in electrification and infrastructure, the dollar will stay high and commodities will be in high demand, elevating prices.

Note that this is a sea-change from the traditional dollar-commodities relationship, and you are reading about it first, here at Ahead of the Herd.

The Federal Reserve appears bound and determined to keep monetary policy tight. Chair Jerome Powell opened the door to a larger half-point rate increase this month (from 0.25%) and said officials are likely to lift rates higher than they previously expected to combat inflation in a stronger economy. (Wall Street Journal, March 7, 2023)

“The latest economic data have come in stronger than expected, which suggests that the ultimate level of interest rates is likely to be higher than previously anticipated,” Powell told the Senate Banking Committee, Tuesday. “If the totality of the data were to indicate that faster tightening is warranted, we would be prepared to increase the pace of rate hikes.”

Meaning more interest rate hike could be on the way. Clearly the Fed will not be knocked off its rate-raising mission early, they won’t be cowed into pausing rate hikes, even though a slower economy, and job losses, are the likely outcome from continued tight monetary policy.

The problem with the Fed’s mission is that governments are working at cross-purposes, investing trillions in electrification, decarbonization, and infrastructure, which is pushing commodity prices higher across the entire commodities spectrum.

Commodities inflation gets passed through to manufactured goods, resulting in higher prices for goods and services, that must be borne by consumers. How long can this historical anomaly of high inflation and high borrowing costs be tolerated by consumers, many of whom are already highly leveraged with mortgages, loans, lines of credit and credit card debt?

US consumers are getting crushed by high-interest debt and inflation

Consumer spending, which makes up two-thirds of global GDP, is going to slow, drastically.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.