The future of Canada’s nickel supply is NOT Indonesia

2021.06.02

China says it has found a way to make “green” nickel chemical for EV batteries from nickel laterite deposits in Indonesia that could help to alleviate the coming supply deficit in the metal that is essential to electric vehicle batteries.

Don’t be fooled. The process itself is extremely polluting, and ‘ocean tailings ponds’ are anything but green. Thankfully car companies aren’t buying it.

Future nickel supply for battery-making is therefore unlikely to come from Indonesia or anywhere else where nickel laterites are mined.

EVs coming to Canada

Canada is in the beginning stages of developing an electric vehicle supply chain that capitalizes on the country’s rich battery metals endowment and cheap hydro-electric power particularly in Quebec and British Columbia.

Over the past six months, three of the world’s largest car companies have announced they are investing in Ontario, Canada’s most populated province and auto sector hub.

General Motors said it will spend close to $1 billion to produce electric commercial vans in Ingersoll, ON, Ford plans to invest $1.2 billion to start building five battery-powered car models in Oakville from 2025, and Fiat Chrysler expects to shell out as much as $1.5 billion in creating its own electric vehicle platform in Ontario.

In Quebec, Lion Electric announced it will build a battery pack manufacturing plant in its home province. The $185 million factory will build lithium-ion battery packs capable of electrifying 14,000 medium and heavy-duty vehicles annually.

The federal government and the provincial governments of Quebec and Ontario have stepped up with hundreds of millions in EV supply chain commitments, recognizing that taxpayer-funded support is needed to help push out such a disruptive technology as vehicle electrification.

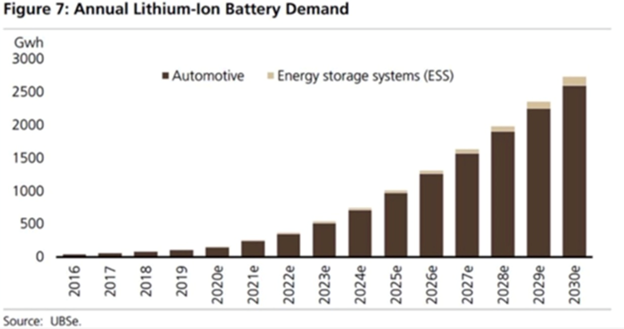

As EV and grid energy storage applications continue to drive up demand for battery minerals, more production of lithium, graphite, and especially, sulfide nickel, will be needed.

As we speak, battery giants and major automakers worldwide are scaling up battery production with mega-factories and actively acquiring battery metals through offtake and joint venture agreements.

Currently, there are over 150 battery mega-factories around the world in the pipeline to 2028 (Benchmark Mineral Intelligence), all of which are based on lithium-ion batteries becoming an all-purpose energy storage unit that is highly scalable.

Nickel overview

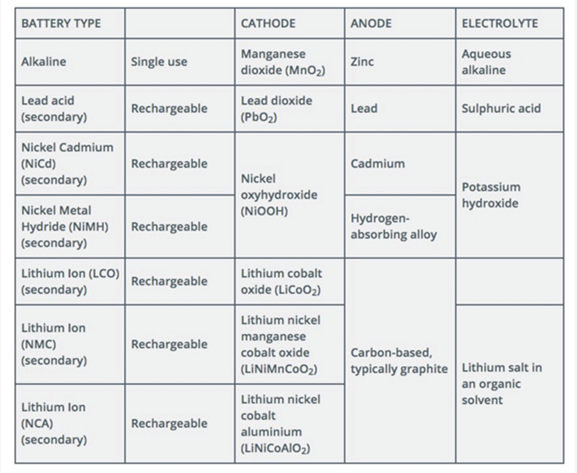

The Nickel Institute informs us that nickel has long been widely used in batteries, most commonly nickel cadmium (NiCd) and in longer-lasting nickel metal hydride (NiMH) rechargeable batteries. The first commercial applications of NiMH batteries came in the mid-1990s, including in the Toyota Prius, camcorders, and eventually, smart phones, laptops and other portable devices. The major advantage of nickel in batteries is it helps to deliver higher energy density and greater storage capacity, at a lower cost.

As the table below shows, nickel is an essential component for the cathodes of many secondary battery designs. (“secondary” refers to batteries that can be recharged and re-used)

Another demand driver for nickel (and other battery metals, like lithium and graphite) is utility-scale energy storage.

Beyond batteries, lot of nickel will still need to be mined for stainless steel, which consumes about 70% of global nickel supply.

According to BloombergNEF, demand for class 1 “battery-grade” nickel is expected to out-run supply within five years, fueled by rising consumption by lithium-ion electric vehicle battery suppliers. Nickel’s inroads are due mainly to an industry shift towards “NMC 811” batteries which require eight times the other metals in the battery. (first-version NMC 111 batteries have one part each nickel, cobalt and manganese).

In fact, Tesla has expressed concern over whether there will be enough high-purity “class 1” nickel needed for electric vehicle batteries. For insurance, the US-based automaker recently inked a supply deal in New Caledonia, a French territory comprising dozens of islands in the South Pacific Ocean. In 2020 Tesla CEO Elon Musk offered nickel miners “a giant contract” to encourage production.

The agreement between Tesla and commodity trader Trafigura Group, reportedly involves the Goro mine in New Caledonia, part of a group that took over operations from Brazil-based Vale.

The deal is significant because it occurred shortly after the largest steelmaker in the world, the Tsingshan Group, announced a novel means (the technology has actually been around for decades) for refining nickel from laterite deposits found in Indonesia, the top nickel-producing country where China’s Tsingshan has been extremely active as of late.

It revealed to the market that Tesla and Trafigura do not see Tsingshan’s new processing method as a cure-all for the nickel industry’s problem of how to meet surging demand for battery-grade nickel — mainly because the process is so polluting. If EV carmakers were to source their nickel battery feedstock from Tsingshan, they would not be able to call it “green”.

To better understand this, we need to explain how nickel is found throughout the world and how it is processed.

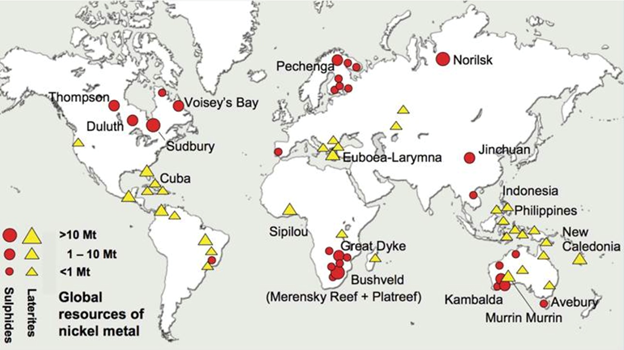

Nickel deposits come in two forms: sulfide or laterite. About 60% of the world’s known nickel resources are laterites, which tend to be in the southern hemisphere. The remaining 40% are sulfide deposits.

Nickel sulfide deposits, the principal ore mineral being pentlandite (Fe,Ni)O(OH), are formed from the precipitation of nickel minerals by hydrothermal fluids. They are also called magmatic sulfide deposits. The main benefit of sulfide ores is that they can be concentrated using a simple physical separation technique called flotation.

Nickel laterite deposits — the principal ore minerals are nickeliferous limonite (Fe,Ni)O(OH) and garnierite (a hydrous nickel silicate) — are formed from the weathering of ultramafic rocks and are usually operated as open pit mines. There is no simple separation technique for nickel laterites. The rock must be completely molten or dissolved to enable nickel extraction. As a result, laterite projects require large economies of scale at higher capital costs to be viable. They are also generally much higher cash-cost producers than sulfide operations.

Yet large-scale sulfide deposits are extremely rare. Historically, most nickel was produced from sulfide ores, including the giant (>10 million tonnes) Sudbury deposits in Ontario, Canada, Norilsk in Russia and the Bushveld Complex in South Africa. However, existing sulfide mines are becoming depleted, and nickel miners are having to go to the lower-quality, but more expensive to process, as well as more polluting, nickel laterites such as found in the Philippines, Indonesia and New Caledonia.

Nickel sulfide deposits provide ore for class 1 nickel users which includes battery manufacturers. These companies purchase the nickel product known as nickel sulfate, derived from high-grade nickel sulfide deposits. It’s important to note that less than half of the world’s nickel is suitable for the biggest growth market — EV batteries.

According to BloombergNEF, demand for class 1 nickel is expected to out-run supply within five years, fueled by rising consumption by lithium-ion electric vehicle battery suppliers. It’s clear that nickel is facing some growing pains since the industrial metal was burnished by its new-found use in the transportation mode of the future.

BNEF analysts note that sales of passenger EVS rose 43% in 2020, a pandemic year, and they forecast a record 4.4 million units will sell this year. Demand for nickel from lithium-ion batteries is expected to surge 16-fold to 1.8 million tons by 2030, BNEF said in a July 2020 report, with batteries accounting for more than half of class 1 nickel demand, “shifting a market that’s currently focused on stainless steel.”

One way to address the coming supply shortage, is to mine plentiful laterites and convert the nickel product into nickel sulfate, as the Chinese are planning to do in Indonesia.

There is an obvious advantage in doing so. Class 1 nickel powder for sulfate production enjoys a large premium over LME nickel prices.

Reuters has reported on the multi-billion-dollar Chinese-led project to produce battery-grade nickel chemicals, that Indonesia hopes will attract EV manufacturers to the country. At least four high-pressure acid leach (HPAL) plants are currently under construction, led by Chinese stainless steel producers and battery makers.

The country expects to double investment in nickel processing to $35 billion in 2035. Jakarta has also signed a $9.8 billion EV battery deal with South Korea’s LG Energy Solution.

Back to Tsingshan and its new processing method, the company plans to supply nickel matte, an intermediate nickel product based on converted nickel pig iron (NPI) used in steelmaking, to Chinese companies Huayou and CNGR Advanced Materials, who will further process it into nickel sulfate.

Trial production of high-purity (>75% Ni) nickel matte began nearly a year ago at its facilities on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, allowing Tsingshan to claim it has the capability of producing high-grade matte on a regular basis.

The company’s announced pivot to nickel matte production in March sent shock waves throughout the industry. The metal suffered its worst two-day rout in a decade, as investors digested the news of Tsingshan’s ability to make battery-grade metal from materials previously reserved for stainless steel only. The implications were clear: the Chinese steelmaker could potentially flood the market. Wall Street banks reacted by cutting their nickel forecasts, following a plunge in nickel futures from about $19,000 to $16,000 per ton.

Yet a short time later, Tesla and Trafigura were linking up in New Caledonia over the Goro nickel mine. Why wouldn’t Tesla just buy their precious nickel sulfate from Tsingshan?

The answer is all about the “green” in green nickel.

Dirty deeds, done dirt cheap

A mentioned there is no simple separation technique for nickel laterites. As a result, laterite projects have high capital costs and therefore require large economies of scale to be viable.

HPAL – whose performance record has been highly mixed — involves processing ore in a sulfuric acid leach at temperatures up to 270 degrees C and pressures up to 600 psi to extract the nickel and cobalt from the iron-rich ore; the pressure leaching is done in titanium-lined autoclaves.

Counter-current decantation is used to separate the solids and liquids. Separating and purifying the nickel/cobalt solution is done by solvent extraction and electrowinning.

The advantage of HPAL is its ability to process low-grade nickel laterite ores, to recover nickel and cobalt. However, HPAL is unable to process high-magnesium or saprolite ores, it has high maintenance costs due to the sulfuric acid (average 260-400 kg/t at existing operations), and it comes with the cost, environmental impact and hassle of disposing of the magnesium sulfate effluent waste.

While the Indonesian government is happy to accept the foreign investment in its burgeoning EV industry, it is no longer willing to tolerate the environmental degradation that laterite nickel production entails.

Recently the country announced it will forbid mining companies from dumping mining waste into the ocean, a practice known as deep sea tailings (DST). To clarify: the government hasn’t actually banned DST, but by not issuing new permits, it could delay planned projects and complicate efforts to dispose of waste, Reuters reported. The lengthy wait means land tailings will eventually become “the only option,” a mining company source told the news outlet.

That, in turn, could affect the economics of any new projects — disposing of the tailings on land, in a nation of islands where space is at a premium — will surely throw a wrench into operations and significantly add to their costs per tonne.

Submarine Tailings Disposal (STD) / Deep Sea Tailings

Consider: although only one nickel mine in Papua New Guinea is using DST, according to the Nickel Institute, most of the four above-mentioned HPAL plants plan to dump their tailings waste into the sea. Reuters quotes a nickel cost researcher at Wood Mackenzie saying, “It would cost a fortune to switch from one established form of tailings disposal to another method.”

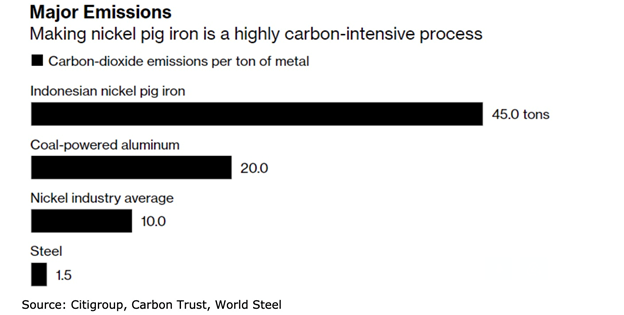

Not only do established nickel miners in Indonesia plan to continue the environmentally egregious practice of DST, due to cost considerations, the process of refining nickel to make nickel pig iron, and now, nickel matte, is highly energy-intensive (it relies on coal-fired power) and creates a lot of air pollution.

According to the graph below, producing 1 ton of nickel in nickel pig iron creates 45 tons of carbon dioxide emissions, compared to just 20 tons for coal-powered aluminum and steel production requiring an average 2 tons of CO2 per ton of metal.

With nickel more carbon-intensive than aluminum, zinc, copper, lead and steel, in that order, automakers are questioning whether they want to have anything to do with Tsingshan’s dirty nickel processing methods, especially in light of the increased importance to most corporations of environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices.

“The technology is definitely real, but does not meet ESG standards,” Bloomberg quotes Jon Lamb, portfolio manager at metals and mining investment firm Orion Resource Partners. “As consumers are focused on the lifecycle carbon intensity of their supply chains it is difficult to see how this production would earn a spot in these supply chains.”

One of the referenced Bloomberg articles has a great quote from mining magnate Robert Friedland, who stated during a recent industry event:

“The automobile industry is not going to nuke hundreds of thousands of acres of tropical jungle in Indonesia and dump the tailings in the ocean and try to convert ferronickel into batteries. That’s disinformation or whistling in the dark.”

The problem is, there actually isn’t that much nickel outside of Indonesia available to mine and process. Miners wanting to bring on new supplies of battery-grade nickel face a number of commercial and technical setbacks, meaning the only location where supply is actually growing is Indonesia.

According to the International Nickel Study Group, via Bloomberg, 2020 production of about 2.4 million tons will need to grow by 1 million tons over the next decade to meet demand from battery-makers. The news outlet quotes Jim Lennon, a senior commodities consultant at Macquarie Securities in London, saying,

“I can’t find 100,000 tons worth of projects that are seriously going to get off the ground outside of Indonesia. So if it’s not Indonesia, it’s nowhere.”

Where will mining companies look for new nickel sulfide deposits, from which the extraction of high-grade nickel needed for battery chemistries is economically and technically feasible? The pickings are slim.

Decades of under-investment equals few new large-scale greenfield nickel sulfide discoveries. Only one nickel sulfide deposit has been discovered in the past decade and a half, Nova-Bollinger in Western Australia.

The result of such limited nickel exploration is a very low pipeline of new projects, especially lower-cost sulfides in geopolitically safe mining jurisdictions. Any junior resource company with a sulfide nickel project will therefore be extremely attractive to potential acquirers.

Renforth Resources

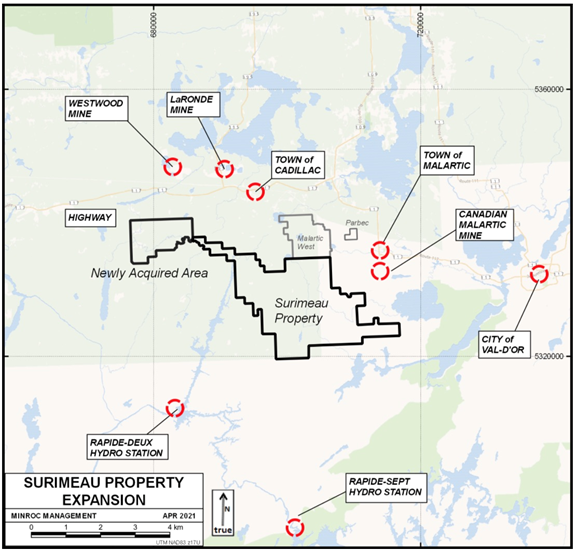

AOTH’s favorite nickel junior is Renforth Resources (CSE:RFR, OTC:RFHRF, WKN:A2H9TN), whose Surimeau nickel sulphide project covers an area of about 260 square kilometers south of the Cadillac Break in Quebec, among current and former producing mines.

The property was up-sized at the end of April, with the addition of 81 claims covering around 4,200 hectares. Surimeau now includes the Huston target located to the west of Renforth’s Surimeau target area, south of Iamgold’s Weswood mine.

In late March, the company commenced a 3,500m drill program which hosts gold, nickel, copper, zinc and other metals in various settings at several locations on the large property. This program, planned to be 16 holes, is on the Victoria West target area, a nickel-rich VMS target that has been explored historically and by Renforth over a strike length of 5 km within a 20-km-long magnetic anomaly associated with intrusives.

To date, Renforth has successfully drilled off 2.2 km of strike length.

What makes Surimeau so intriguing is that unlike many copper-zinc VMS systems around the world, this property also happens to host an ultramafic sulfide nickel system at surface nearby.

While the scale of this nickel sulfide system remains to be seen, Renforth considers it to be representative of another “Outokumpu-like” occurrence, referring to a district in eastern Finland known for several unconventional sulfide deposits with economic grades of copper, zinc, nickel, cobalt, silver and gold. Between 1913 and 1988, about 50 million tonnes of ore averaging 2.8% Cu, 1% Zn and 0.2% Co, along with traces of Ni and Au, were mined from three deposits in that district.

Historic surface sampling in the Victoria target area on the Surimeau property had values as high as 0.503% Ni. Such findings were later supported by Renforth’s exploration team from grab sampling in summer 2020, which returned values up to 0.495% Ni.

Conclusion

A nickel discovery at Surimeau could prove to be significant, especially considering the bull market for nickel we are seeing, the result of soaring demand for battery-grade nickel, matched against a dearth of nickel sulfide deposits, and the serious environmental problems associated with processing nickel laterites and dumping mine tailings into the sea.

Nickel sulfide deposits containing “the right kind of nickel” are extremely rare. Where can automakers and battery manufacturers go to source high-quality nickel sulfides needed to feed their supply chains? As this article has made abundantly clear, Indonesia and its dirty nickel processing methods render this type of laterite nickel out of bounds, for any self-respecting company claiming to be producing a green EV or a clean battery.

As Canada moves forward in its nascent mine-battery-EV supply chain, I predict that high-quality, scalable sulfide nickel deposits like Renforth’s Surimeau will be in high demand.

Renforth Resources

CSE:RFR, OTC:RFHRF, WKN:A2H9TN

Cdn$0.09 2021.06.01

Shares Outstanding 251m

Market cap Cdn$22.9m

RFR website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Richard does not own shares of Renforth Resources (CSE:RFR). RFR is a paid advertiser on Richard’s site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.