The case for low-grade sulfide nickel deposits

2022.10.04

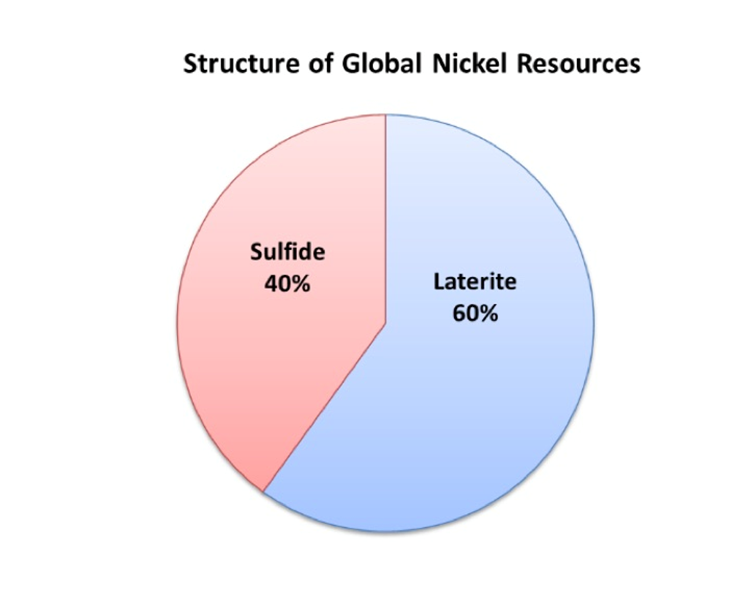

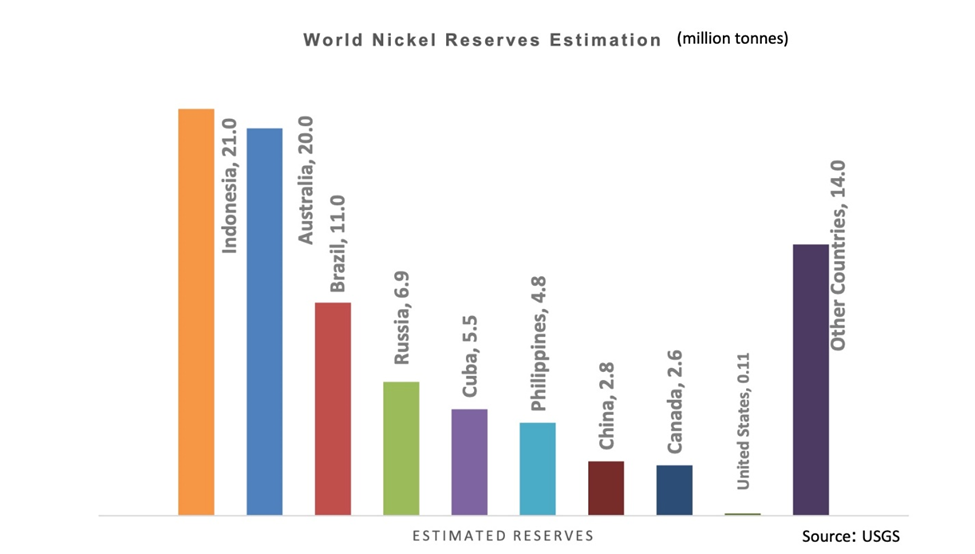

Nickel deposits come in two forms: sulfide or laterite. About 60% of the world’s known nickel resources are laterites, which tend to be in the southern hemisphere. The remaining 40% are sulfide deposits.

The main benefit of sulfide ores is that they can be concentrated using the fairly simple flotation technique.

There is no such technique for nickel laterites. The rock must be completely molten or dissolved to enable nickel extraction. As a result, laterite projects require large economies of scale at higher capital costs to be viable. They are also generally much higher cash-cost producers than sulfide operations.

Nickel laterite deposits were first discovered in 1864 by French civil engineer Jules Garnier in New Caledonia — commercial production started in 1875. New Caledonia’s laterites were the world’s largest source of nickel until Sudbury Ontario’s sulfide deposits started production in 1905 and totally dominated global production.

However, existing sulfide mines are becoming depleted, and nickel miners are having to go back to the lower quality, but more expensive to process, as well as more polluting, nickel laterites such as found in the Philippines, Indonesia and New Caledonia.

With laterite ores, counter-current decantation is used to separate the solids and liquids. Separating and purifying the nickel/cobalt solution is done by solvent extraction and electrowinning.

High-Pressure Acid Leach (HPAL) plants that treat the ore require much bigger investments than sulfide operations — there is often significant cost and technical challenges associated with laterite projects.

HPAL, which has a highly mixed performance record, involves processing ore in a sulfuric acid leach at temperatures up to 270C and pressures up to 600 psi to extract the nickel and cobalt from the iron-rich ore — the pressure leaching is done in titanium-lined autoclaves.

Because it uses sulfuric acid, HPAL comes with the cost, environmental impact and hassle of disposing the magnesium sulfate effluent waste. Top nickel producer Indonesia only recently banned the practice of dumping tailings into the ocean for new smelting operations, and it isn’t yet a permanent ban.

Chinese nickel pig iron producers in Indonesia now are looking to make nickel matte, from which to turn laterite nickel into battery-grade nickel for EVs.

The process however is highly energy-intensive and polluting, more so than HPAL and about four times dirtier than traditional nickel sulfide processing.

A recent Bloomberg article has a great quote from mining magnate Robert Friedland, who stated:

“The automobile industry is not going to nuke hundreds of thousands of acres of tropical jungle in Indonesia and dump the tailings in the ocean and try to convert ferronickel into batteries. That’s disinformation or whistling in the dark.”

Still, projects worth billions are in the works to produce battery-grade nickel chemicals, that Indonesia hopes will attract EV manufacturers to the country.

Among them is Tesla, which has expressed concern over whether there will be enough high purity “Class 1” nickel needed for electric vehicle batteries. Battery makers like nickel because it stuffs more energy into cheaper and smaller battery packs, allowing for faster charging and longer ranges.

In 2020 Elon Musk offered nickel miners “a giant contract” to encourage production. Apparently he wasn’t too picky about where it came from.

In March of that year Tesla signed a contract with Vale-NC to supply intermediate mixed nickel and refined cobalt produced in New Caledonia. Vale is the world’s largest nickel producer, with mines in Brazil, Canada and Indonesia.

Under the agreement, Tesla would use Caledonian nickel-cobalt sourced from the Goro mine for its Berlin-Brandenburg Gigafactory. In 2021 New Caledonia’s Prony Resources bought the loss-making nickel and cobalt operation from Vale, then signed an offtake agreement with Tesla guaranteeing the automaker about 42,000 tonnes of the metal.

Although the end products would supposedly meet Europe’s social and environmental standards, we note that nickel mined in the South Pacific French territory is laterite. The only way for battery-grade nickel to be produced is through the highly polluting HPAL method.

In 2020 Indonesia imposed a ban on the export of raw nickel ores. Therefore, if Tesla wanted to secure its nickel, it would have to invest in processing within the country.

Stripped of its ESG credentials, Tesla continues to pursue dirty nickel in Indonesia

Ten years ago I wrote about nickel laterite versus sulfide projects. Many of my original points are still valid. Consider:

- Decades of underinvestment equals few new large-scale greenfield nickel sulfide discoveries — since 1990, the only large greenfield discoveries happened when exploration was going on for other metals: Voisey’s Bay was diamond exploration, Kabanga was gold exploration, and when Enterprise was discovered in Zambia they were looking for copper. Very little project development and exploration has been done over the past few years for nickel. The result has been a limited pipeline of new projects, especially lower-cost sulfide projects in geopolitically safe mining jurisdictions.

- Increased political risk, population and economic growth are causing the exploitation of lower-grade, larger deposits in riskier countries to mine in. Generally sulfide deposits are found in more politically stable jurisdictions (e.g. Canada, Australia, Greenland) versus laterite deposits (Indonesia, Philippines, PNG, New Caledonia, many parts of Africa).

- Sulfide minerals require much less energy to liberate nickel than laterites.

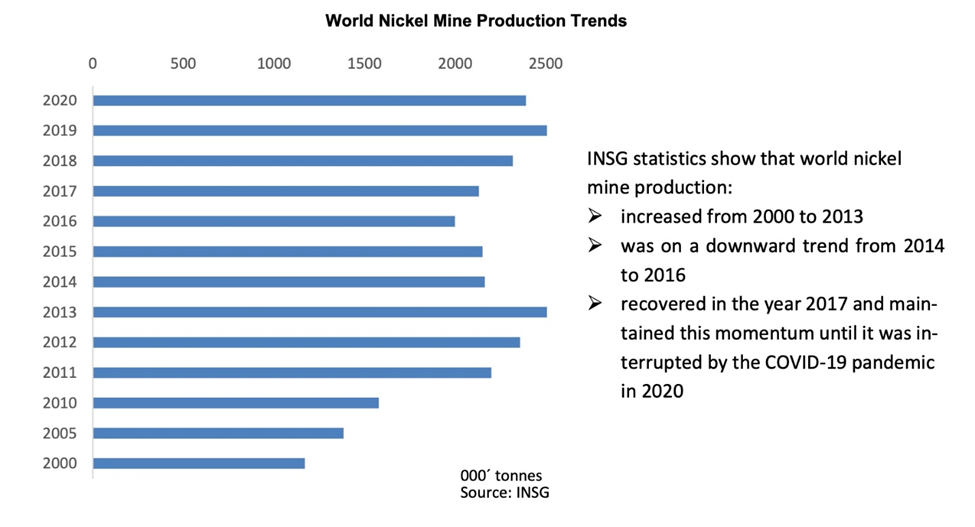

- China is the leading consumer of nickel and is competing for supplies with US industrial demand, as well as India, Russia and Brazil. Exploration and development are subject to bubbles. Capital requirements are huge and the time required to bring in new capacity is measured in decades.

Canada Nickel offers the following additional points regarding nickel supply, and the attraction of lower-grade nickel sulfide deposits as sources of new nickel outside of Indonesia.

Regarding nickel supply:

- Nickel supply is facing increasing political risk as Indonesia now dominates nickel supply growth. Just three countries are expected to control as much of the nickel supply as OPEC did of global oil supply at its peak in 1973: New Caledonia, the Philippines and Indonesia.

- Nickel supply has a “dirty nickel” issue: 100% of recent growth and the bulk of future growth comes from Indonesian supply — not a solution for a number of consumers due to its massive carbon footprint, poor ESG performance, and integrated Chinese supply chains.

- The nickel project pipeline outside Indonesia largely emptied during the last super-cycle in the mid-2000s, and there have been few nickel sulfide discoveries – the last 1Mt high-grade sulfide discovery was Voisey’s Bay in 1992.

- The best discoveries in the last decade (NovaBollinger, Sakatti) are too small to move the needle. Each of their entire resource represents only one to two quarters of potential Tesla nickel consumption by 2030.

Regarding the advantages of low-grade nickel sulfides over laterites:

- Large-scale – several deposits with +2 million tonnes of contained nickel

- Scalable production – typically open pit mine/mill operation readily expanded

- Potential for zero/low carbon footprint particularly where zero carbon hydroelectricity available

- Many located in low political risk jurisdictions

- Some deposits (like Crawford) are close to significant infrastructure;

- Typically standard mine/mill facilities utilizing commonly used technology

- Inherently less energy intensive

- Less capital intensive as smelting/refining facilities don’t always need to be constructed – can ship a concentrate.

Lower-grade nickel supply

With most of the world’s high-grade nickel sulfide deposits mined out, it is falling to the lower-grade projects to fill the supply gap. This begs the question, asked by Crux Investor: Can Low-Grade Bulk Nickel Ever Be Profitable? The short answer is yes.

Author William Hughes begins proving his case by noting that:

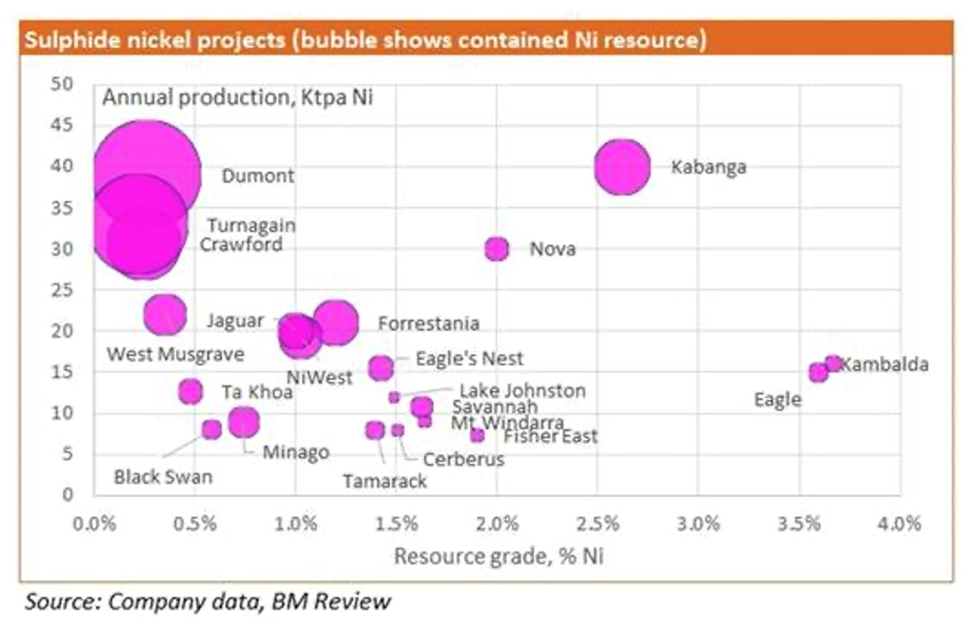

Large scale low-grade ultramafic nickel deposits, such as the one the fund manager mentioned specifically, Crawford (Canada Nickel), and other similar deposits like Dumont (Waterton), FPX (Baptiste) are the only potential multicycle scalable sources of large quantities of nickel required to meet massive new nickel demand from electric vehicles and continued strong growth from stainless steel. The original example of this type of deposit is [Australia’s] Mt. Keith — successfully built and operated by BHP’s nickel business for more than 25 years as one of the largest nickel sulphide mines in the world.

BHP has now developed a similar scale sister deposit — Yakabindie, and [last] year, acquired the Honeymoon Well deposit. While many investors are familiar with high-grade nickel discoveries in Western Australia, and Sudbury – it is important to note that [low-grade] Mt. Keith has remained open through many nickel cycles while the high grade deposits at Kambalda [Western Australia] have been shut for many years — highlighting some insights into the underlying economics.

Hughes then looked at the operating costs of two shovel-ready nickel projects in Canada — the Dumont cobalt-nickel project in Quebec (Waterton Global Resource Management); and the Crawford project being developed by Canada Nickel.

Dumont, which is operating in the same area as Canada Nickel, is currently incurring costs of CAD$10 per tonne. Other low-grade base deposits in British Columbia, for example Taseko’s Gibraltar copper mine, Teck’s Highland Valley copper mine, and Centerra Gold’s Mount Milligan copper-gold mine, also have operating costs around $10/t.

The question then becomes, how much revenue can be generated by processing a tonne of ore? Note that not all of the nickel will be recoverable, due to the silicate minerals in it. Ultramafic nickel deposits always contain an amount that is non-recoverable by standard flotation circuits, with recoveries in the 40-50% range not uncommon.

Canada Nickel’s Crawford nickel-cobalt-PGE project has a measured and indicated resource (higher-grade core) of 280 million tonnes @ 0.31% Ni, 0.013% Co, and 0.04 g/t Pd + Pt, within an overall M&I resource of 653Mt @ 0.26% Ni and 0.013% Co.

Using Crawford as an example, Hughes finds that, based on a nickel price of USD$17,000 per tonne, and using the roasting process from Dumont’s feasibility study, the higher-grade ore would deliver CAD$34 per tonne and the lower-grade ore would fetch $23 per tonne.

Based on the CAD$10/t operating cost, the higher-grade ore results in an operating margin greater than 65%, and the average grade operating margins are over 50%. For reference, Dumont’s cash costs in the feasibility study are USD$3.20/lb and the project has an all-in-sustaining cost (AISC), life of mine, of $3.80/lb.

Those are some healthy profit margins. But Hughes recognizes that there are more valuable, lower-risk paths for lower-grade deposits to take to market. For example, FPX Nickel’s Baptiste-Decar Project in north-central British Columbia near Fort St. James, creates a product that can be shipped directly to the stainless steel industry, while the Dumont Project has a simple process that allows nickel concentrates to be utilized by any ferronickel or nickel pig iron (NPI) producer. Waterton, says Hughes, indicates this process at Dumont would yield a payability of 90-95% versus 70-75% for traditional smelting.

Moreover, the process isn’t theoretical; it has been successfully employed by the world’s largest nickel and stainless steel producer, China’s Tsingshan Group. Proving the viability of this method, Tsingshan started building their first fluid bed roaster in 2014 and have since added a roaster, dramatically increasing their output.

The company has processed a range of range of concentrates as a part of an offtake agreement with Western Areas, and even successfully processed the world’s worst nickel concentrates from South Africa, says Hughes, who concludes that:

Hopefully, these real-world examples highlight that, while not currently “typical” nickel deposits, these large, low-grade deposits can be very profitable even at their low grades and recovery levels, as the revenue generated from each tonne of material is a multiple of the operating costs. The copper industry moved to large low-grade deposits several decades ago and a generation of companies generated hundreds of millions/billion of dollars for shareholders by advancing these projects during the prior past 2 decades. These nickel deposits represent a whole new generation of investment opportunities which could be even more lucrative for those investors prepared to do the work and trapped in investment paradigms that stopped being meaningful 20 years ago. If these type of deposits are good enough for BHP Billiton, they should be good enough for the rest of us.

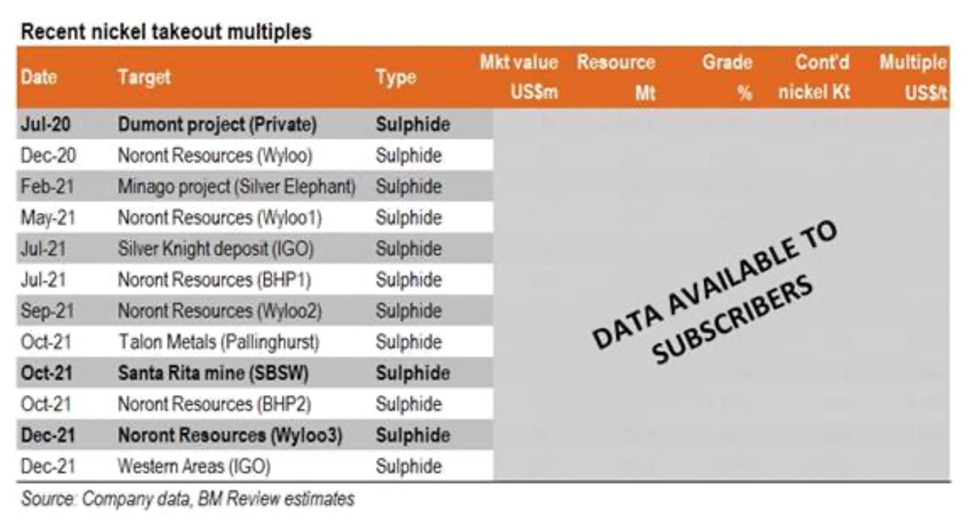

A Kitco commentary last year by Matt Fernley, editor of Battery Materials Review, talks more about the profitability of low-grade sulfide nickel deposits — especially for major miners that have shown increasing interest in them.

A great example is Sibanye Stillwater’s acquisition of Santa Rita in Brazil, one of the largest nickel-cobalt-sulfide mines in the world. The overall resource grade of the project (open pit and underground) amounts to just 0.54% nickel, but as Fernley notes, the take-out multiple was much higher than the previous multiple for a major low-grade sulfide project, Dumont, which was acquired in 2020. (Note: Sibanye Stillwater in January of this year abandoned the $1 billion deal to buy the Santa Rita nickel mine and Serrote copper-gold mine in Brazil after a “geotechnical event”, so the asset is still up for grabs).

Like Crux Investor author Hughes, Fernley proffers a copper example to demonstrate the viability of low-grade nickel. Chilean copper producer Antofagasta operated the highly successful Los Pelambres copper porphyry mine, with EBITDA of US$2 billion per annum, and an NPV of around $11bn with a $3.25/lb ($7,166/t) long-term copper price. The 2013 copper head grade at Los Pelambres was 0.69%.

According to the PEA, Canada Nickel’s Crawford project has a nickel head grade starting at 0.32%, falling to 0.25% by phase 3. Based on its cost assumptions and a nickel price of USD$7.75/lb, the project could yield EBITDA of $287M per annum in phase 1, rising to $538m pa thereafter.

As of Sept. 30, the spot nickel price in New York was $9.48 and the spot copper price was $3.43/lb, so nickel is worth 2.7X the price of copper.

Last October, when Fernley converted the Los Pelambres’ 2013 copper head grade of 0.69%, to nickel equivalent (nickel then was 2X copper), its head grade worked out to be 0.34%. Today the head grade has fallen to 0.63%, making it bang in line with Canada Nickel’s Crawford project initial head grade [of 0.32%] in nickel equivalent terms.

As for whether small, high-grade nickel mines are preferable to large, low-grade mines, Fernley argues that, from a mining point of view it’s simpler and cheaper to mine a large tonnage open pit than it is a high grade, underground occurrence, particularly as those high-grade mines get older and the operating areas move further away from the shaft or decline.

Most Australian sulphide projects are in the ballpark of 1.2-1.8% nickel in resources, but the occurrences are much smaller. This in turn supports lower production over shorter mine lives. This is why you don’t find too many Majors operating in WA. While the projects are often very profitable they don’t scale enough to excite the Majors.

Increasingly then, the Majors are looking to the sort of bulk tonnage, lower grade sulphide projects which have historically been shunned by investors.

Ask yourself, “when is the best time to invest in nickel?”

While you mull over that question here are five facts:

- Nickel is currently unloved. While nickel prices shot higher in March following the war in Ukraine, they have been more than cut in half — part of a cross-the-board metals selloff due to recession fears. This week, Bloomberg reported that nickel sales by commodities-dealing banks hit by soaring borrowing costs have caused spot contracts to plunge to the deepest discount to futures since the 2008 financial crisis.

Nickel goes parabolic on historic LME short squeeze

- There aren’t any nickel names left. Without Inco or Falconbridge, who do you invest in if you want nickel? The largest nickel-producing companies, Norilsk, Vale and Glencore (formerly Xstrata) don’t actually provide a lot of leverage to nickel as they are diversified miners — meaning they also produce iron ore, manganese, bauxite, aluminum, copper, coal, cobalt, potash, platinum-group metals, gold and silver.

- Every country needs to secure nickel at competitive prices yet supply is increasingly constrained and demand is growing, especially for nickel used in electric-vehicle batteries. Wood Mackenzie estimates that of the 2.8 million tonnes demanded last year, 69% was used to make stainless steel and 11% to make batteries, up from 71% and 7% respectively in 2020. Batteries’ share of demand is expected to rise to 13% in 2022. According to Rystad’s latest report, nickel demand from the stainless-steel industry should grow at about 5% per year, while the market for batteries is poised to explode. “In an unconstrained supply scenario, batteries could require more than 1Mt of nickel metal by 2030, quadrupling from the current demand of 0.25Mt,” the energy research firm said.

World’s running short on nickel supply for battery use

- Juniors exploring for nickel from sulfide ore deposits have become much more interesting. Especially so if they are working in geopolitically stable countries.

- Pure junior sulfide nickel exploration plays aren’t common.

Renforth Resources

Meeting new emissions targets being set by countries like Canada, the US, Britain, and Japan, will mean large-scale deployment of electric vehicles, renewable power, and electrical transmission, all of which will require copious metal content.

With an abundance of battery metals and cheap hydroelectric power, particularly in British Columbia and Quebec, Canada is uniquely positioned to become an EV leader, from the mining and processing of metal ores, all the way up to the manufacture and assembly of electric and hybrid vehicles.

As one of the few junior miners racing towards the next sulphide nickel discovery in Canada, Renforth Resources (CSE:RFR, OTCQB:RFHR, FSE:9RR) has the right metals at the right time, embodied in its Surimeau polymetallic project in Quebec.

Like Dumont in Quebec and Crawford in Ontario, Surimeau fits into the large-scale, low-grade nickel sulfide model we’ve been discussing. But there are other aspects that make it truly unique.

The project hosts several areas prospective for gold/silver and battery/ industrial metals (nickel, copper, zinc, cobalt and lithium). It is located south of the Cadillac Break, a major regional gold structure.

The property occurs within a unique geological setting where two types of mineralization, formed from different geological processes, are “mashed together” in one distinct orebody. It is best described as a magmatic nickel sulfide deposit, juxtaposed with a copper-zinc volcanogenic massive sulfide (VMS) deposit.

The first type of deposit, which contains nickel, cobalt and platinum group elements (PGEs), is associated with ultramafic rocks. The second type, VMS, was formed on or near the ocean floor during ancient underwater volcanic activity.

VMS deposits are sought after for mining because they usually contain a mix of base metals such as zinc, lead, copper, and sometimes precious metals including silver and gold. The minerals often form massive sulfide mounds or layers, making them relatively easy to extract.

Surimeau’s mixed style of mineralization, however, is very rare; the best comparison so far is the Outokumpu district of eastern Finland.

Outokumpu contains sulfide deposits with economic grades of copper, zinc, cobalt, nickel, silver and gold. Mining took place from 1913 to 1988, and involved the exploration of three deposits — Outokumpu, Vuonos and Luikonlahti. Approximately 50 million tonnes of ore, averaging 2.8% Cu, 1% Zn and 0.2% Co, along with traces of Ni and Au, were mined.

Up until now, Renforth has mainly focused on the polymetallic “battery metals” package of nickel, cobalt, copper, zinc, platinum and palladium that is present in at least six known areas of the property. This year the company is looking to broaden its exploration efforts at Surimeau by including lithium.

On top of lithium, Renforth will also look for rare earth elements by following up on various geochemical anomalies in the SIGEOM system to determine if they are pegmatites and/or REE occurrences. This includes a highly anomalous scandium value in the NW portion of the property that is 3x higher than any other scandium value in the dataset. At this location, the REEs dysprosium and neodymium also gave unusually high values.

Exploration results to date have reinforced Renforth’s view that Surimeau is richly endowed with battery metals like nickel and cobalt that have been largely overlooked in the past.

The Victoria mineralized structure is estimated at about 20 kilometers long, and the Lalonde structure now measures 9 km in length. The company continues to define the surface and sub-surface polymetallic mineralization, evidenced by outcrops, drill results and geophysics.

However, a significant amount of ground remains untested, leaving heaps of upside for Renforth shareholders, in a project that is already showing district-size scale.

According to Renforth, new outcrop mineralization discovered near the center of the ~20 km Victoria mineralized structure, delivered a grab sample of 0.71% Ni (nickel) in rock described as “albitized ultramafic with sulfides”.

This is the second band of mineralization found north of previous drilling at the Victoria target. The results were from field work targeting the polymetallic intrusive mineralization at Surimeau during this past May and June.

At the Lalonde target, two assay results of 0.32% nickel from two separate grab samples were obtained within the current stripping area at Lalonde West. According to Renforth, the sampling program at Lalonde has delivered consistent elevated values from the exposed mineralized horizon.

Renforth samples 0.71% Ni from unexplored part of Surimeau

Exploration at Surimeau has also focused on sulfide nickel-rich VMS targets, in particular the Victoria West prospect.

Information gleaned from drilling and trenching, along with surface sampling, creates an area of interest that includes over 5 kilometers of strike on the western end of an ~20-kilometer magnetic anomaly.

The company interprets this anomaly to be a nickel-bearing ultramafic sequence unit, which occurs alongside, and is intermingled with, VMS-style copper-zinc mineralization.

So far, only 5,626 meters have been drilled over 2.2 km of the known strike length, yielding results that allude to the presence of a large polymetallic camp richly endowed with nickel, copper, cobalt and zinc, along with some PGEs (platinum group elements).

Assays came from seven holes (1,200m) drilled within the 275m strike length of the stripped area at Victoria West, where channel sampling earlier revealed consistent nickel-cobalt mineralization.

It appears to me that Renforth is in the early stages of outlining a large polymetallic system at Surimeau, including battery metals nickel and cobalt, plus copper, zinc and platinum group elements, in Quebec, a jurisdiction that consistently ranks highly among mining investment attractiveness.

“Our entire conversation is predicated upon ourselves only drilling 2.2 km of the 20-km system. We’ve barely scratched the surface,” CEO Nicole Brewster said in a company video shot in July.

Stay tuned for more news from Renforth, which continues to develop, potentially, Canada’s next supply of battery-grade sulfide nickel.

Renforth Resources

CSE:RFR, OTCQB:RFHRF, FSE:9RR

Cdn$0.03; 2022.09.30

Shares Outstanding 262.3m

Market cap Cdn$8.4m

RFR website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Follow me on Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.