Shutdown of deep ocean current could cause extreme climate change as soon as 2025 – Richard Mills

2024-02-14

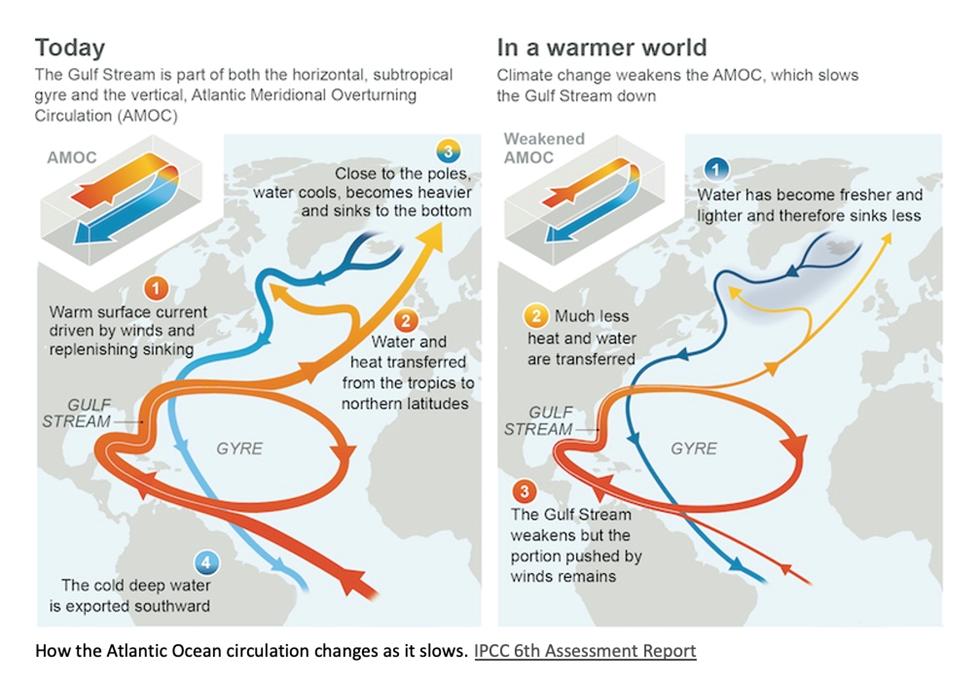

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a large system of water currents that circulates water from north to south and back, in a long cycle within the Atlantic Ocean.

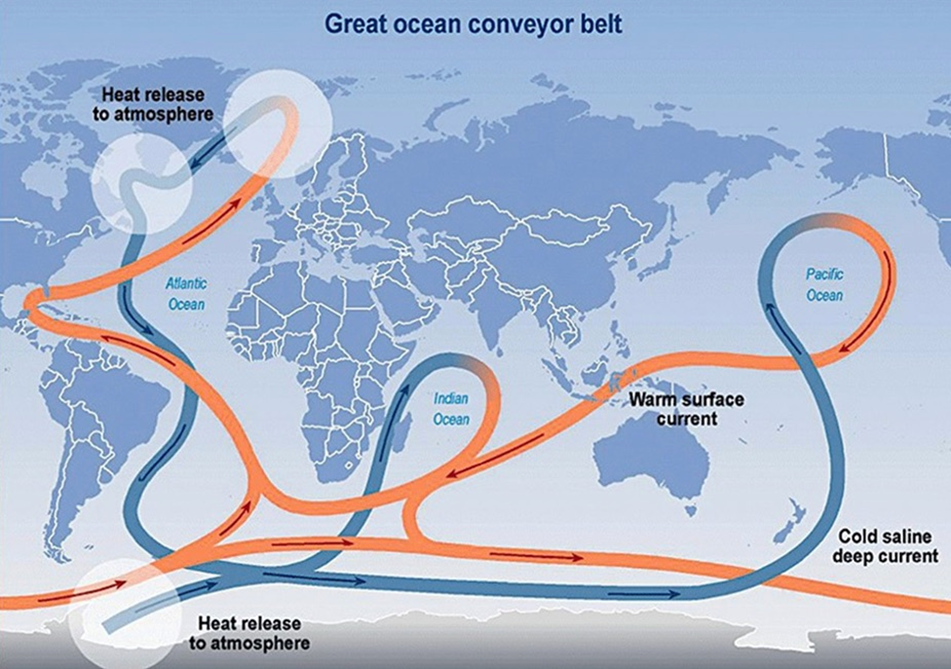

This system of deep-water circulation, sometimes referred to as the Great Ocean Conveyor Belt, sends warm water from the Gulf of Mexico to the North Atlantic, where it releases heat to the atmosphere and warms Western Europe. The cooler water then sinks to great depths and travels all the way to Antarctica and eventually circulates back up via the Gulf Stream (see below).

Right off the bat, we need to distinguish between the Gulf Stream and the AMOC.

It’s the AMOC that has been in the news lately about slowing down and potentially coming to a stop sometime in the next 70 years, as early as 2025 but no later than 2095, according to research.

By contrast, experts say there is zero chance of the Gulf Stream collapsing and causing wintry conditions in Europe. A climate scientist quoted by Big Think says as long as the wind blows and the Earth rotates, the Gulf Stream will continue to function.

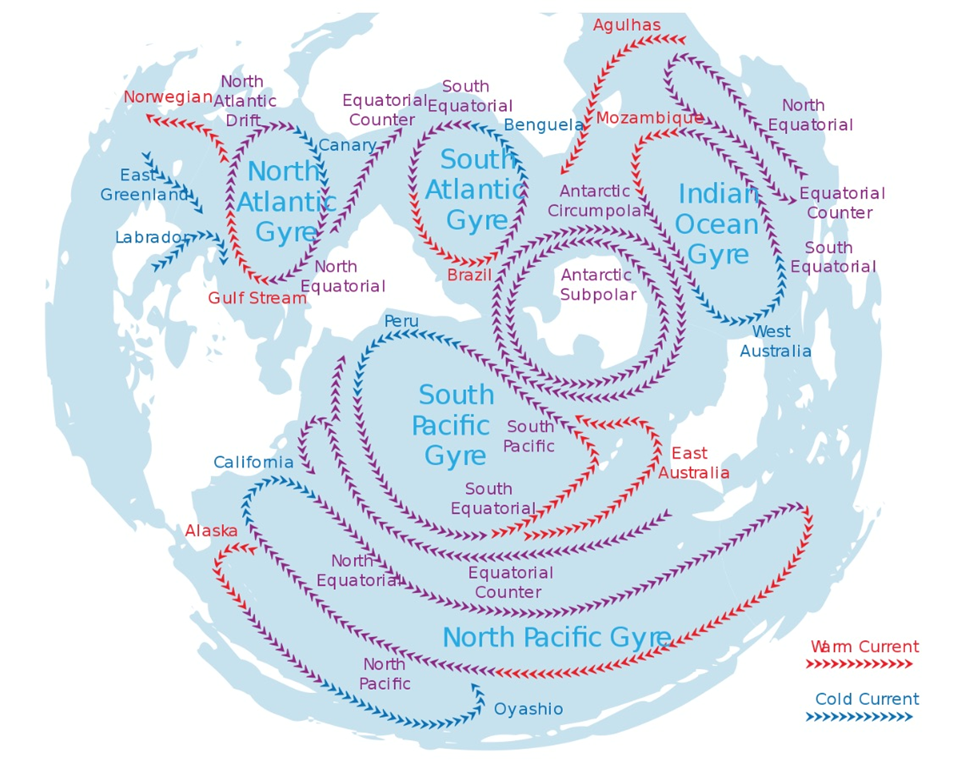

To be clear, the Gulf Stream originates in the Gulf of Mexico, hence its name, carrying 30 million cubic meters of water per second as it passes Florida, then heads south of Newfoundland. It has a warming effect on the US Eastern Seaboard, then the coast-hugging current bends into the Atlantic Ocean and splits into the Canary Current, which turns south in a clockwise direction, and the North Atlantic Current, which flows counterclockwise towards Europe.

Thanks to the North Atlantic Current, northwestern Europe’s climate is much milder than it would otherwise be.

Every major ocean basin has similar currents, all caused by the Coriolis effect. Due to the Earth’s rotation, air and water veer right in the Northern Hemisphere and left in the Southern Hemisphere.

Source: Big Think, Wikipedia

Back to the AMOC, it “begins with the sinking of cold, salty water in the Norwegian and Greenland Seas, [from] where it slowly spreads back south, well below the surface,” states Dr. Jonathan Fowley, climate scientist and executive director of Project Drawdown.

The water is pushed down in huge, rotating columns called chimneys, some of which churn almost to the bottom of the ocean, 2.5 km from surface.

Little is known about these mysterious structures except that there are less of them, and that their reduction corresponds with loss of ice (a survey done in 2004 found only two chimneys in the Greenland Sea, whereas previous surveys found many more chimneys).

Watch the circulation of the currents in this video

Without climatic disruptions, the currents work to move water around the globe, along with nutrients key to the survival of marine species.

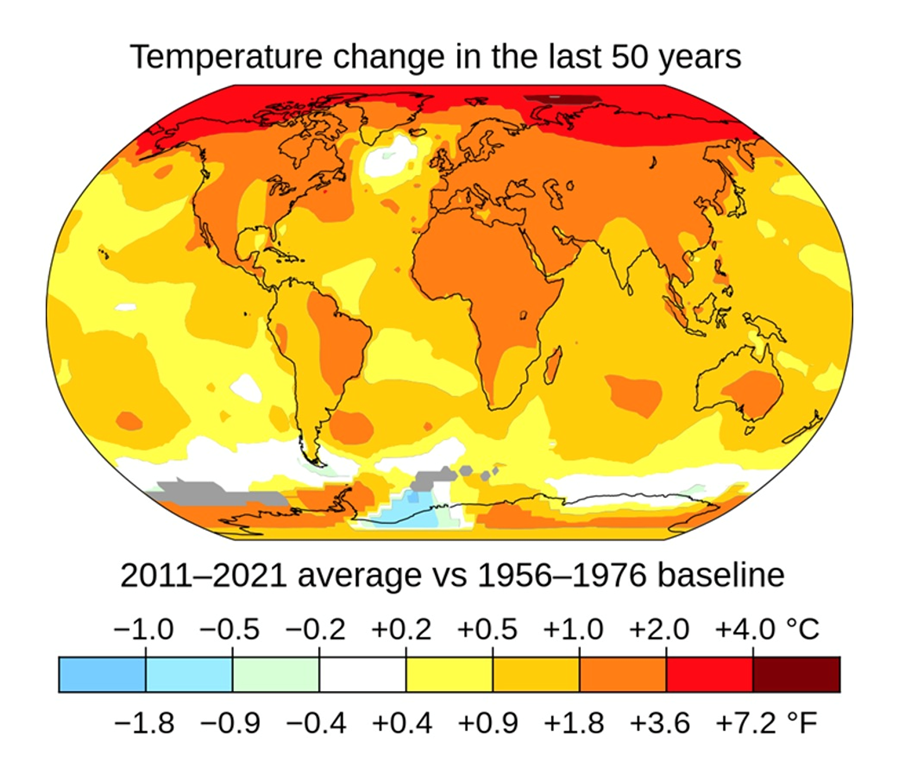

But climate scientists have been raising concerns that rising temperatures are throwing a wrench into the conveyor-like currents system. Sensors stationed along the North Atlantic show that the volume of water moving northward has been sluggish, potentially affecting sea levels and weather. If the AMOC were to stop altogether, it could bring extreme climate change within decades, not centuries, or millenia — a period so short it wouldn’t even register in geologic time.

Slowing current

New research reveals this key cog in the global ocean circulation system hasn’t been running at peak strength since the mid-1800s, and is currently at its weakest point in the past 1,600 years.

According to a 2018 study published in science journal ‘Nature’, the AMOC has weakened over the past 150 years by approximately 15-20% due to the influx of freshwater from melted ice entering the system. (more on that below)

Another study published in the same issue of ‘Nature’ looked at climate model data and past sea-surface temperatures and found that the AMOC has been weakening more rapidly since 1950 in response to global warming.

Together, these two studies provide complementary evidence that the present-day AMOC is exceptionally weak, which could have serious implications for Europe’s weather as well as the rest of the world.

Another 2021 study in ‘Nature and Climate Change’ warned of “an almost complete loss of stability of the AMOC over the course of the last century.” Furthermore, the study, which used eight datasets looking at surface temperatures and salinity in the North Atlantic over a period of 150 years, found global warming was driving the destabilization.

In an email to CNN, via CTV News, study author Niklas Boers, from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, said a collapse of the circulation would mean significant cooling in Europe, “but maybe more concerning is the effect of an AMOC collapse on the tropical monsoon systems of South America, Western Africa, and India; especially in Western Africa, an AMOC collapse could lead to permanent drought conditions.”

The National Ocean Service confirms that, while it is uncertain whether the AMOC will continue to slow down or stop, if the planet keeps warming, fresh water from melting ice at the poles would shift the rain belt in South Africa, causing drought for millions of people. It would also cause sea level rise across the US East Coast.

A 2023 study in ‘Nature Communications’, reported via CBC News, said if the AMOC were to shut down, England and France would suddenly get a colder climate similar to southern Canada, damaging their ability to grow food; heat up northern Africa; and bring more storms and cause changes to rain and snow in Eastern Canada and the US, including drying of the mid-American plains.

The study says the collapse will happen far sooner than the previous estimate, a tipping point of +4 degrees C. (more on that below)

Source: Zhengyu Liu, CBC News

Melting ice

The reason the AMOC is slowing is due to the melting of Greenland’s ice cap and Arctic sea ice. Dense salt water in the North Atlantic is getting swamped by an influx of lighter fresh water from the melting ice.

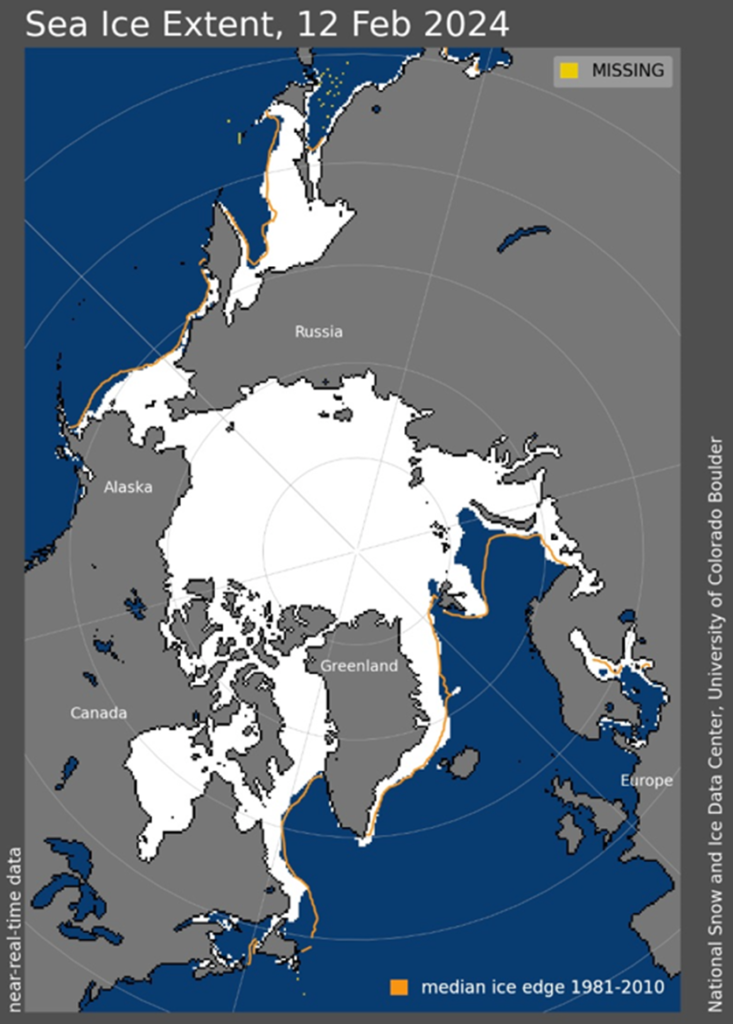

Scientists have found that the Arctic is heating up four times faster than the rest of the world. Much of this has to do with the phenomenon known as “Arctic amplification”, or the loss of sea ice.

Shrinking Arctic sea ice means more extreme weather patterns — Richard Mills

The Arctic Ocean is mostly covered with a layer of sparkling sea ice. But as the planet warms, the sea ice begins to dissipate and exposes more of the oceans surface warming the water, the loss of ice allows more heat to escape from the warmer water into the colder atmosphere. And as more ice vanishes from the sea, Arctic temperatures rise faster, which in turn makes the sea ice vulnerable to further melting.

The lowest peak coverage occurred in 2017, when the ice extended over just 14.4 million square kilometers before beginning to shrink. According to NSIDC recordings, five of the lowest maximum extents have occurred since that year, and the 10 lowest coverage years have all taken place since 2006.

Melting ice at the north pole and around Antarctica could lead to a cascade of effects on the world’s climate patterns. Sea ice already plays a key role in regulating the world’s temperature, as its bright surface reflects 50-70% of sunlight back into space. But as sea ice melts in the summer, it exposes the dark ocean surface which instead absorbs 90% of the sunlight, raising the temperature of the ocean, and the cycle of melting-warming intensifies.

Record-setting heat on Earth could well be the norm in the coming years — Richard Mills

Source: ‘Nature Communications’

It’s not only melting sea ice, but receding glaciers.

Greenland’s glaciers hold the equivalent of six meters of water should they melt into the ocean. The melting of Greenland would affect the North Atlantic Current and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. The amount of freshwater pouring into the ocean from glacial melt would effectively stop the normal circulation of water around the globe, causing a sudden deep freeze.

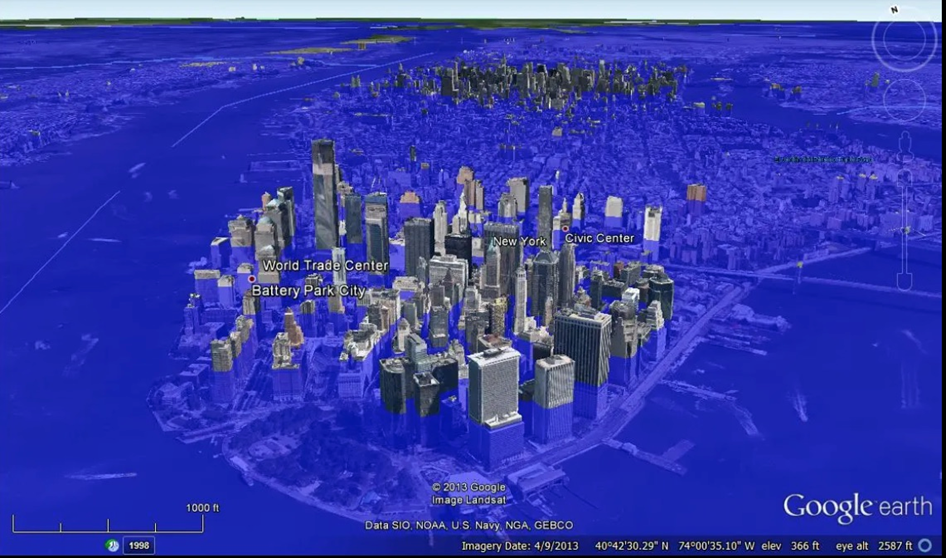

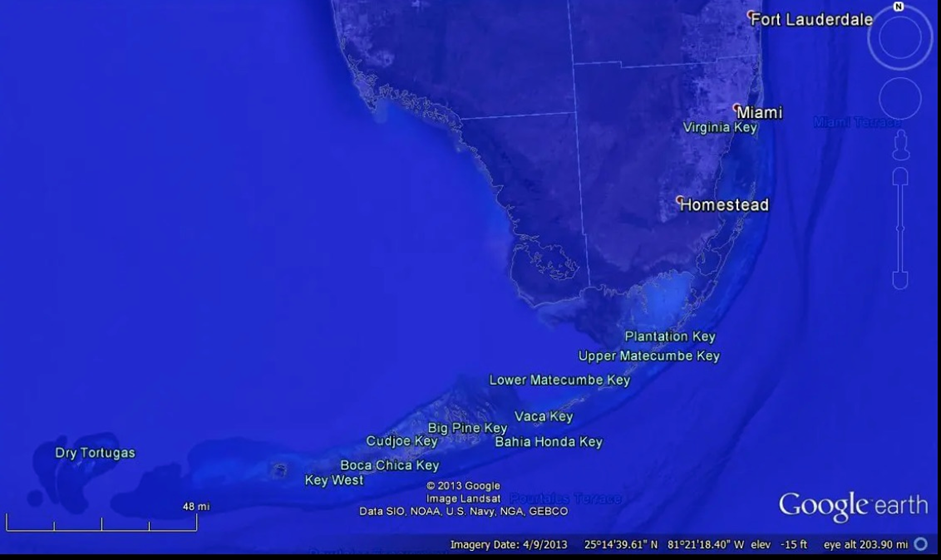

Sea levels would rise up to seven meters, inundating big cities like New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, London, Tokyo, Hong Kong, the entire state of Florida and vast swaths of Indochina.

The melting of the Antarctic ice sheet is even scarier. That would cause a sea rise of 80 meters, or up to five meters in the next 100 years if the West Antarctic Ice Sheet starts calving.

According to Carbon Brief, 2023 was the 27th year in a row in which Greenland lost ice. The world’s largest island saw the disappearance of 197 billion tonnes of ice from September 2022 to August 2023 — close to the 1981-2010 average.

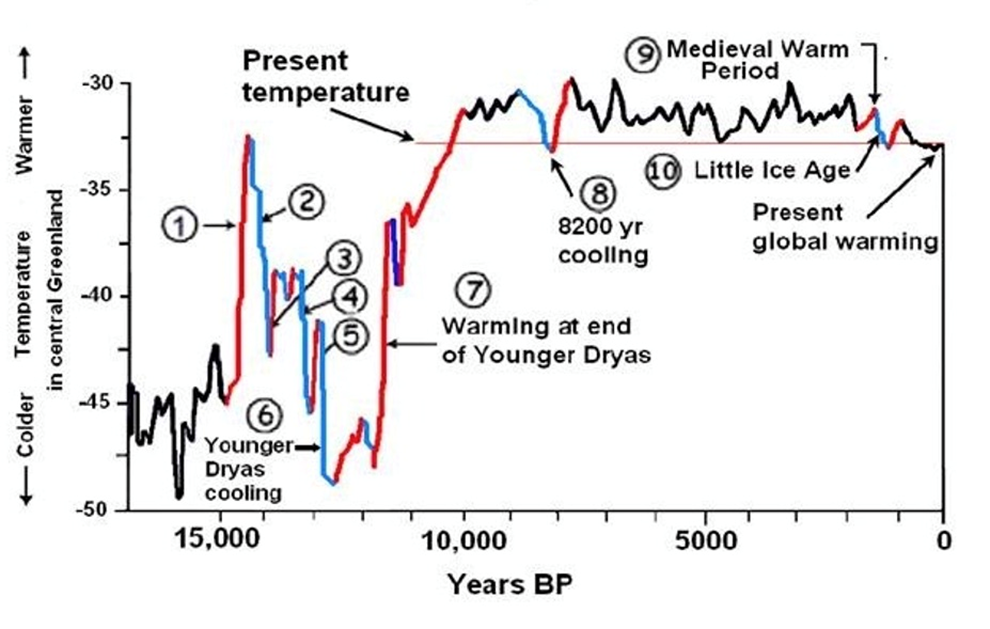

The Younger Dryas

The last time the AMOC shut down was 12,000 years ago, during a near-glacial period known as the Younger Dryas.

The term is sometimes employed to explain the natural cycles of global warming and cooling. It refers to an interruption in the heating of the climate that occurred after the last global ice age that started receding about 20,000 years ago.

The prevailing theory of what caused an abrupt freezing involves a large influx of fresh water from a very large lake, called Lake Agassiz (now the Great Lakes), into the Atlantic Ocean likely via the St. Lawrence Seaway, which stopped the AMOC in its tracks, plunging Europe and much of the northern hemisphere into a relatively short ice age.

For example there is geological evidence of a sharp decline in temperature between the Pleistocene epoch and the current Holocene epoch.

Within decades temperatures dropped 2 to 6 degrees C, causing the advance of glaciers and dry conditions. The mini-ice age is thought to have lasted between 1,000 and 1,300 years, and like it started, also ended abruptly, within 40 to 50 years.

Another intriguing theory that supplements the Younger Dryas explanation of the sudden onset of an ice age involves a comet striking the Earth. The website Science details the story of a geologist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, who gathered proof of a 31-kilometer wide impact crater under a kilometer-thick sheet of ice known as the Hiawatha Glacier, in Greenland. Some researchers on his discovery team believe the massive impact on the ice sheet would have sent meltwater surging into the Atlantic Ocean, thereby disrupting the conveyor belt of ocean currents — just as the spilling of the contents of Lake Agassiz did.

Could it happen again?

Applying the Younger Dryas theory to current global warming, and all the evidence we have of it, including melting sea ice, glaciers and permafrost, rising sea levels, disruptions to the polar vortex, freak storms, heat waves, forest fires, etc., it’s interesting to speculate what could happen.

We know that during the Younger Dryas, a long period of global warming after the last major ice age suddenly ended and resulted in “global cooling”. Is that what’s in store for planet Earth, if we compare our current warming trend? If so, Europe won’t be so worried about heat waves, but instead, could be looking at a frozen landscape more resembling ‘A Game of Thrones’.

Then again, the climatic conditions of today are totally different than 12,000 years ago. How will the depletion of Arctic sea ice, warming oceans, melting permafrost causing huge volumes of methane to escape into the atmosphere, collapsing polar vortices, when tossed into the equation of a warming planet, that may or may not be human-caused or just due to natural causes, affect our future climate?

Tipping point

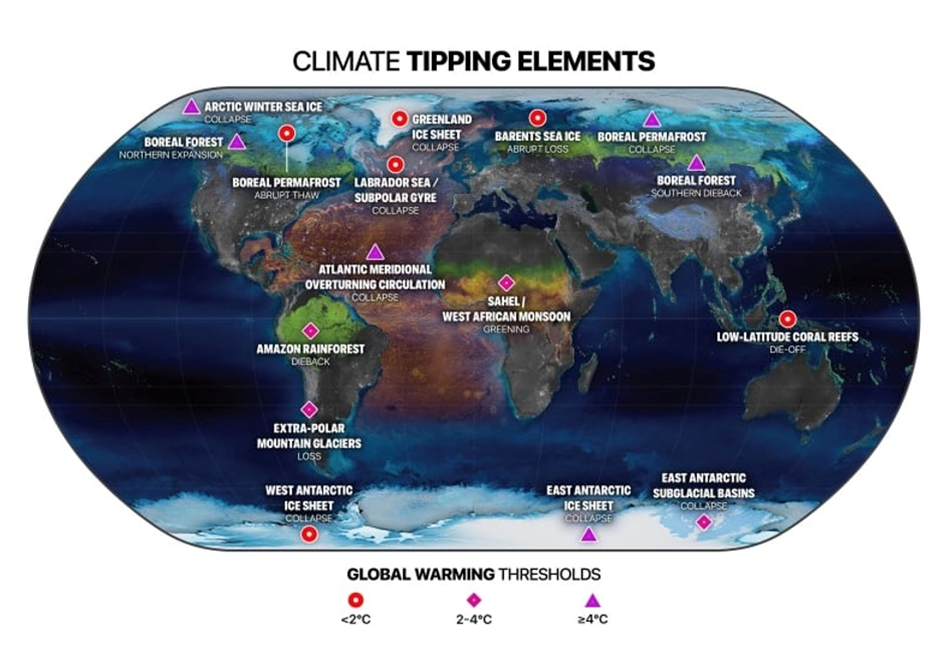

Climate science has been able to discern a past tipping point that led to relatively sudden, irreversible climate impacts, and a recent study shows it could hit that tipping point again, as warming continues.

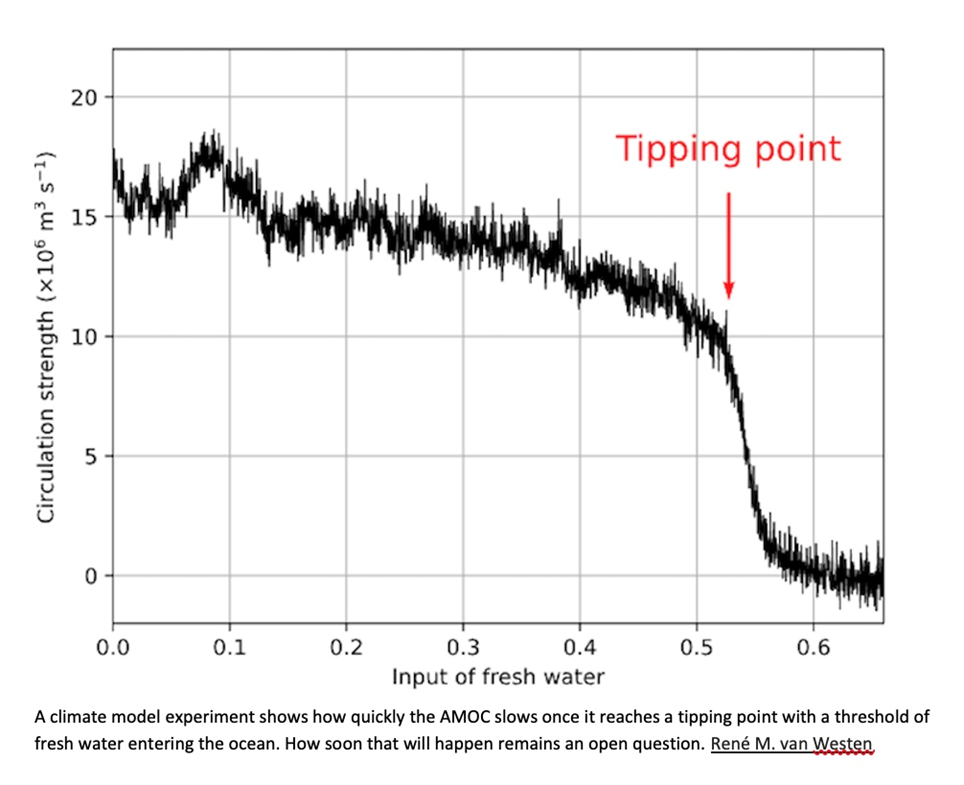

According to The Conversation, a tipping point was first noticed in a simple model of the Atlantic Ocean circulation in the early 1960s. Today’s climate models indicate continued slowing of the conveyor belt under climate change, but without an abrupt slowdown.

A new study performed an experiment with a detailed climate model to

find the tipping point for an abrupt slowdown by slowly increasing the amount of fresh water. The results showed the circulation could shut down within 100 years of hitting the tipping point.

When the circulation stops, parts of Europe cool by more than 3 degrees Celsius per decade — much faster than present global warming of about 0.2 C per decade. In Norway, the mercury could fall as much as 36 degrees. Regions in the southern hemisphere, on the other hand, would warm by a few degrees.

Source: The Conversation

The slowdown and eventual stoppage of the AMOC would also affect sea level and precipitation patterns. The Conversation says this would push other ecosystem closer to their tipping points, such as the Amazon rainforest. Declining precipitation turns the forests into grassland, releasing carbon into the atmosphere and accelerating global warming.

So when exactly is the tipping point? To determine this, the study developed a kind of early-warning signal involving the transport of salty water at the southern boundary of the Atlantic Ocean. Once a threshold is reached, the tipping point, seen below in red, is likely to follow in one to four decades.

The above-mentioned study in ‘Nature Communications’ is more alarming in its findings.

The study says the AMOC could disappear as soon as 2025, and no later than 2095, and that we’re much closer to the tipping point that will trigger the current’s demise than previously thought.

This, in my opinion, is the most important takeaway from this article.

Consider: earlier estimates had the tipping point at roughly 4C of warming. So far the Earth’s surface has only warmed about 1.3C. The last time the AMOC collapsed, 12,000 years ago, temperatures plunged between 10 and 15 degrees within a decade.

While the researchers say it won’t trigger an ice age like in the movie ‘The Day After Tomorrow’, the AMOC’s collapse will: give England and France a climate similar to southern Canada, thus damaging those countries’ ability to grow food; heat up northern Africa, which is already experiencing extreme heat and droughts; and bring more storms, rain and snow to the east coast of Canada and the US, along with drying of the mid-American plains.

How can the researchers tell we are nearing a tipping point? Key signs are wild swings to extreme temperatures, and slower returns to the average temperature. Researchers saw evidence of both at the end of the last ice age 12,000 years ago, when the AMOC collapsed.

CBC News wrote, In the case of the AMOC, researchers have been measuring its temperature, which they’ve correlated to other measurements made with satellites, submarine cables and moored instruments since 2014.

Using that temperature correlation allowed them to estimate AMOC over a longer period of time, back to 1870. In doing so, the researchers noticed signs that a tipping point is approaching. By extrapolating, they’ve estimated when that is — sometime in the next two to 72 years.

“I think one of the major take-home messages from our paper is that it could possibly happen much earlier than what is believed,” said Susanne Ditlevsen. “And I think that’s very worrisome.”

A warning

If we believe the ‘Nature Communications’ study, we have between one and 71 years to go, before the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation stops moving, causing abrupt climate changes — up to 15 degrees colder or warmer — within a decade. This is based on the last time the AMOC collapsed, 12,000 years ago. But the planet is much worse off than it was then. Along with rapid warming at the poles, and melting sea ice and glaciers, we have melting permafrost causing huge volumes of methane to escape into the atmosphere, collapsing polar vortices, and extended droughts happening all over Earth.

Even the milder study quoted by The Conversation, has the tippling point for an AMOC shutdown, measured by the salinity of the water in the southern Atlantic, likely to follow in one to four decades.

Remember, the AMOC shutdown is directly related to polar ice melt, a feedback loop that gets worse every year that more open sea is exposed to the sun. If the Greenland ice sheet disappears, sea levels would rise up to seven meters, inundating big cities like New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, London, Tokyo, Hong Kong, the entire state of Florida and vast swaths of Indochina.

The melting of the entire Antarctic ice sheet would cause a sea rise of 80 meters. For an idea of what this would mean for some major US cities, and other vulnerable parts of the world, check Southern Fried Science.

Let’s run a little doomsday scenario.

Imagine, now you have melting ice to the point where the Arctic Ocean is ice-free all year round. There are no more glaciers. The spring freshet each year is very short because the only snow and ice in the mountains is from the last season.

Many of the world’s coastal cities have been flooded by rising sea levels. Coastal aquifers are ruined by saltwater intrusion, causing widespread water shortages. Vast dead zones appear in the ocean after pollutants wash into the seas from industrial areas like refineries that were inundated. There is no-one to clean up the mess.

Anyone who has the means, escapes from the coasts into the interior. But there they find that fresh water is scarce due to no glaciers, much depleted lakes and dry stream beds. Droughts are common in summer and there are problems around food security. Prices of staples like wheat, corn and rice skyrocket.

The planet has warmed several degrees C, and is getting warmer. There is already searing heat in the summer, along with energy-sapping humidity. There are global, massive constant burning fires, so smoke adds to the greenhouse effect.

Conflicts become common, we’re fighting over scarce resources.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.