Rushing headlong into electrification, the West is replacing one energy master with another

2022.01.07

The United States and its allies, such as Canada, the UK, the European Union, Australia, Japan and South Korea, face a dilemma when it comes to the global electrification of the transportation system and the switch from fossil fuels to cleaner forms of energy.

On the one hand, we want everything to be clean, green and non-polluting, with COP26-inspired goals of achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050; and several countries aiming to close the chapter on fossil-fuel-powered vehicles, including the United States which is seeking to make half of the country’s auto fleet electric by 2030.

Yet many of these same countries are continuing to go flat-out in their production of oil and natural gas — considered a bridge fuel between fossil fuels and renewables, wrongly imo, for environmental reasons — a/ because they want to be energy-independent; and b/ because they have to. Germany is a good example of a country that tried to switch too soon to renewable energy, retiring its nuclear and coal power plants, only to find that the wind and sun didn’t produce enough electricity. Germany is now having to rely on Russian natural gas and the burning of lignite coal to keep the lights on and homes/ businesses heated throughout the winter.

We all remember (well those that are old enough do) the long gas station lineups of the 1970s during the OPEC oil embargo. At that time, the US was almost 100% dependent on Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states for its crude oil.

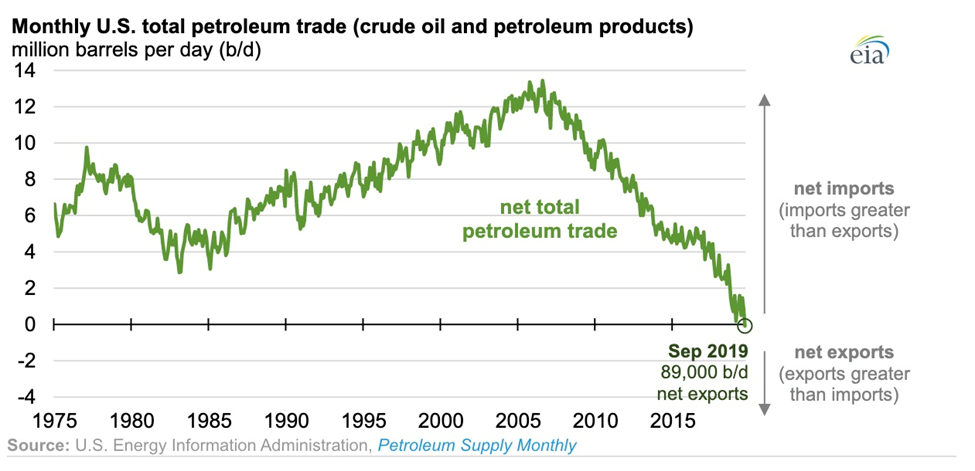

Well times have changed and the US is supposedly energy-independent — in September 2019 the United States exported 89,000 barrels per day more petroleum (crude oil and petroleum products) than it imported, the first month this happened since monthly records began in 1973.

Now the materials required for a modern economy are those needed for electrification and decarbonization — metals like lithium, graphite, nickel and cobalt for EV batteries; copper for wiring, motors and charging stations, as well as renewable energy systems; silver for solar cells, and rare earths like neodymium for wind turbines.

The problem is, getting to 100% renewables, if that is even possible (I’d say more like 40%, if we’re lucky) will require more metals than are currently available in the world’s mines. Shortages are forecasted by 2030 for cobalt, copper, lithium, natural graphite, nickel and rare earths. Moreover, getting those minerals in the amounts demanded means going to some environmentally unfriendly places, including Indonesia for sulfide nickel, the DRC for cobalt, and China for rare earths.

The irony is, the rush to “go green” carries with it the simple fact that the mining of this stuff is anything but. Yet because Western countries like Canada and the US haven’t bothered to develop their own mine to electric vehicle, or mine to renewable energy plant supply chains, they are dependent on imports. EVs and solar/wind sound green, but how green are they when the materials are being imported from places like Indonesia, which allows tailings to be dumped into the sea, and the extremely polluting HPAL method of separating laterite nickel into the end product used in batteries?

It all comes down to security of supply. Western countries don’t have it, because they haven’t bothered to mine, or refine, domestically and continue to rely on imports especially from China but also South Africa and Russia.

And we can’t forget fossil fuel dependency because many countries cannot, and will not, build the infrastructure needed to decarbonize/ electrify.

They will continue to require huge amounts of coal, oil and natural gas. Even Europe, supposedly on the leading edge of “green”, relies heavily on Russian gas, as we shall see below. Japan, which has no natural resources of its own, in 2020 imported the majority of its oil from Saudi Arabia. And Australia, despite being a mining powerhouse (coal, iron ore), will by 2030 be 100% reliant on imported petroleum, due to the ongoing closure of its refineries.

Our addiction to oil means that hybrid vehicles, obviously requiring gasoline, are expected to continue outpacing full electrics for years.

When it comes to energy, we have in effect replaced one master, Saudi Arabia which ruled the global oil markets for decades, with China, which “owns” the EV supply chain. And despite eco-dreams of killing off fossil fuels, they remain very much in the picture, with Russia lording power over European gas imports, for example, and Japan and Canada continuing to rely heavily on Middle Eastern oil.

Even if we wanted to reduce our dependence on these countries, the mining industry faces significant local opposition to mineral exploration, mining, processing and smelting. Ironically, the greens who require all these minerals, to go electric, are the same people opposing their extraction.

Carmakers plugging in

It all starts with demand.

Global automakers have latched onto the electrification trend and are going great guns to deliver new models to a reticent public getting keener on plug-ins.

While Tesla dominated the early days of electric vehicles, Elon Musk’s baby is in the cross-hairs of Volkswagen and Toyota, who are reportedly planning on spending $170 billion to knock Tesla off its perch.

“When the two biggest car companies in the world decide to go all-in on electric, then there’s no longer a question of speculation — the mainstream is going electric,” Bloomberg quoted Andy Palmer, the former chief of Aston Martin and ex-Nissan Motor Co. executive, in a recent story.

In early December, VW CEO Herbert Diess announced $100 billion will be going into EV and software development over the next decade. The iconic German company already has the Audi e-tron and the Porsche Taycan, and last year came out with two new offerings, the ID.3 hatchback and ID.4, an SUV. The MEB platform underpins 27 EV models Volkswagen sported at the end of 2021. The number of factories they will be built in has been increased from five to eight, including VW’s US assembly plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Facing criticism for being late to the space, Toyota has stepped up its EV game. (while the Japanese company is known for its trail-brazing Prius hybrid, Toyota’s first mass-market global EV isn’t set to debut until the middle of this year)

Of the $70 billion Toyota is dedicating to electrification by the end of this decade, half will go to fully electric models, Bloomberg reports. The carmaker plans to sell 3.5 million EVs a year by 2030, almost double its earlier target.

A couple of months ago Akio Toyoda, grandson of the company’s founder, made headlines for introducing a Corolla Sport H2 Concept vehicle with a hydrogen-fueled engine. Following a spin around a racetrack, Toyoda announced plans to come out with 30 new EV models within the next eight years.

This week GM unveiled its new electric Chevrolet Silverado pickup, as buzz grows for the truck’s future rival, the Ford F-150 Lightning, set to go on sale this spring.

Top dog Tesla, meanwhile, is aware of the competition nipping at its heels. Last year the California-based firm nearly doubled its production, delivering over 936,000 vehicles. $188 billion is being plowed into its Shanghai plant to take production beyond its 450,000 units a year capacity, with Tesla’s two new assembly plants, one in Germany and one in Austin, TX, gearing up to start making Model Ys, Bloomberg reports.

All the big carmakers all try to out-do one another in bringing out new electric-vehicle models, yet arguably, they are getting ahead of themselves. There are still major obstacles to greater EV penetration, the main ones being sticker shock, limited range, charging station availability, and charge times. While it might make sense for urban dwellers to run EVs to and from work and charge them at home, residents living in rural areas or in cold winter climates may find electrics inappropriate, even dangerous, say if they are caught in a traffic jam in freezing temperatures.

Then there is the problem of raw materials supply — being able to find the minerals and metals needed, and to mine them responsibly and sustainably.

The EV “revolution” has also glossed over a very important point: going green comes with a cost — energy security.

We tackle each of these topics in turn.

We don’t have the metals

The adage “if it can’t be grown it must be mined” serves as a reminder that electric vehicles, transitional energy, and a green economy start with metals. The supply chain for batteries, wind turbines, solar panels, electric motors, transmission lines, 5G — everything that is needed for a green economy — starts with metals and mining.

The fossil-fueled based transportation system needs to be electrified, and the switch must be made from oil, gas, and coal-powered power plants to those which run on solar, wind and thorium-produced nuclear energy. If we have any hope of cleaning up the planet, before the point of no return, a massive decarbonization needs to take place.

Commodities consultancy Wood Mackenzie said an investment of over $1 trillion will be required in key energy transition metals over the next 15 years, just to meet the growing needs of decarbonization.

Transportation makes up 28% of global emissions, so transitioning from gas-powered cars and trucks to plug-in vehicles is an important part of the plan to wean ourselves off fossil fuels.

Kozak and O’Keefe forecast EVs will make up about 15% of new car sales by 2025, doubling to 30%, or 30 million EVs, by 2030.

A green infrastructure and transportation spending push will mean a lot more metals will need to be mined, including lithium, nickel, and graphite for EV batteries; copper for electric vehicle wiring and renewable energy projects; silver for solar panels; rare earths for permanent magnets that go into EV motors and wind turbines; and silver/ tin for the hundreds of millions of solder points necessary in making the new electrified economy a reality.

In fact, battery/ energy metals demand is moving at such a break-neck speed, that supply will be extremely challenged to keep up. Without a major push by producers and junior miners to find and develop new mineral deposits, glaring supply deficits are going to beset the industry for some time.

According to a report by UBS, a deficit in nickel will come into play this year, for rare earths in 2022, for cobalt in 2023, and in 2024, for lithium and natural graphite.

Moreover, the Swiss investment bank predicts large deficits by 2030 for each of these metals: 170,000 tonnes for cobalt, equal to 42% of the cobalt market; 10.9 million tonnes of copper (about half of current global mined production), representing 31% of the market; 2.1Mt for lithium (50% market share); 3.7Mt for natural graphite and 2.2Mt for nickel (both 37%); and 48,000 tonnes for rare earths, equivalent to 47% of the market.

In a thought experiment, we at AOTH crunched the numbers for what it would take to get to 100% renewables. The amount of raw materials required is “off the charts”.

Wind and solar energy do not happen without mining, and they take unbelievable amounts of metals. Just replacing the current amount of energy demanded by coal and natural gas, let alone inevitably higher figures in future, with solar and wind, we calculated it would take over 60,000 solar farms and more than 120,000 wind farms. In all it’s about a 450% increase in renewables.

Ain’t gonna happen, folks. We will run out of metals long before we reach that level of renewable energy capacity. In fact we would be surprised if we even make it to 40%. Without a concerted and global push to mine more, the prices of the required metals will keep climbing, crimping demand for them.

We already know that we don’t have enough copper for more than a 30% market penetration by electric vehicles. For solar power we are talking about finding 16 times the current annual production of aluminum, and 23 times the current global output of copper. Up to six times the current production levels of nickel, dysprosium and tellurium are expected to be required for building clean-tech machinery.

Even if the mining industry could identify and produce this amount of metals to meet the world’s goal of 100% decarbonization, the supply shortages guaranteed to hit the markets for each would make them prohibitively expensive. It’s just supply and demand.

Something nobody in the clean-tech, green-energy space likes to talk about is the “dark side of green”. This can be seen as a hidden cost of electrification/ decarbonization.

In Indonesia, nickel is produced from laterite ores using the environmentally damaging HPAL technique. The advantage of HPAL is its ability to process low-grade nickel laterite ores, to recover nickel and cobalt. However, HPAL employs sulfuric acid, and it comes with the cost, environmental impact and hassle of disposing the magnesium sulfate effluent waste. The Indonesian government only recently banned the practice of dumping tailings into the ocean for new smelting operations, and it isn’t yet a permanent ban.

Chinese nickel pig iron producers in Indonesia now are looking to make nickel matte, from which to turn laterite nickel into battery-grade nickel for EVs. The process however is highly energy-intensive and polluting, as well as far more costly than a nickel sulfide operation (up to $5,000 per tonne more). According to consultancy Wood Mackenzie, the extra pyrometallurgical step required to make battery-grade nickel from matte will add to the energy intensity of nickel pig iron (NPI) production, which is already the highest in the nickel industry. We are talking 40 to 90 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per tonne of nickel for NPI, versus under 40 CO2e/t for HPAL and less than 10 CO2e/t for traditional nickel sulfide processing.

What’s the point of making supposedly “green” battery components when the refining process is so dirty?

The mining industry may have achieved progress in recent years regarding environmental, social and governance (ESG), the new corporate buzz word, but in parts of the (mostly) developing world, the industry is still sporting a black eye.

Mining practices in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have elevated the issue of “conflict minerals” to the public consciousness, with stories of armed groups operating cobalt mines dependent on child labor, as well as in Guinea, where riots have broken out over bauxite mining.

Rare earths mining and processing in China, the extraction and refining of laterite nickel in Indonesia, and cobalt mining in the Congo, are three good examples of the disconnect between the rhetoric being delivered lately regarding the so-called new green economy, and reality.

In many respects the widely touted transition from fossil fuels to renewable energies, and the global electrification of the transportation system, are not clean, green, renewable or sustainable.

Ok. Enough about the mounting costs of electrification/ decarbonization and the pending shortages of metals.

There is a more immediate problem that decarbonization has brought about, and that is high electricity costs.

The cost of electrification/ decarbonization

To put it bluntly, ridding the planet of fossil fuel-generated power — coal, oil, and natural gas — is untenable. Not only are solar and wind inappropriate for base-load power, because their energy is intermittent, and must be stored in massive quantities, using battery technology that is still in development, they don’t have anywhere near the energy intensity provided by fossil fuels, or nuclear.

Driven by the need to decarbonize due to increasingly apparent climate change, governments around the world right now are choosing to de-invest from oil and gas, and instead are plowing funds into renewable energies even though they aren’t yet ready to take the place of standard fossil-fueled baseload power, i.e., coal and natural gas.

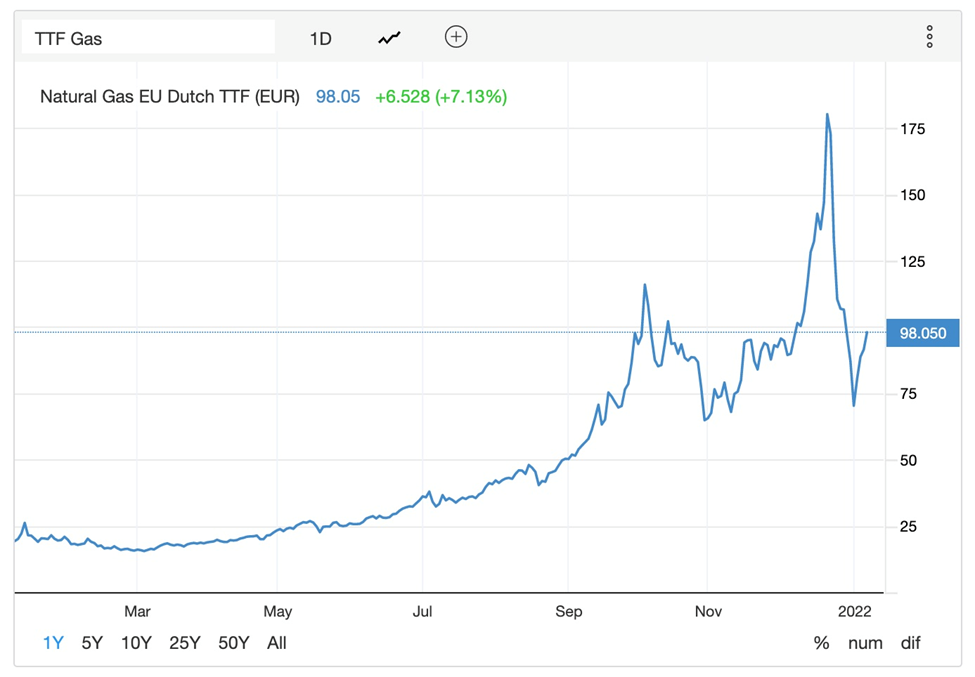

We have seen this foolish endeavor playing out in Europe, where natural gas prices are hitting records due to coal plants being shut down as well as nuclear plants shelved, such as in Germany and France. The skyrocketing cost of electricity is being borne by ordinary citizens who had no part in this dumb policy of “premature decarbonization”.

Saudi Arabia has warned that, without re-investing in the oil industry to find more deposits, the world could be short 30 million barrels a day in just eight years.

In the current under-supplied environment, high oil and natural gas prices will be with us for the foreseeable future.

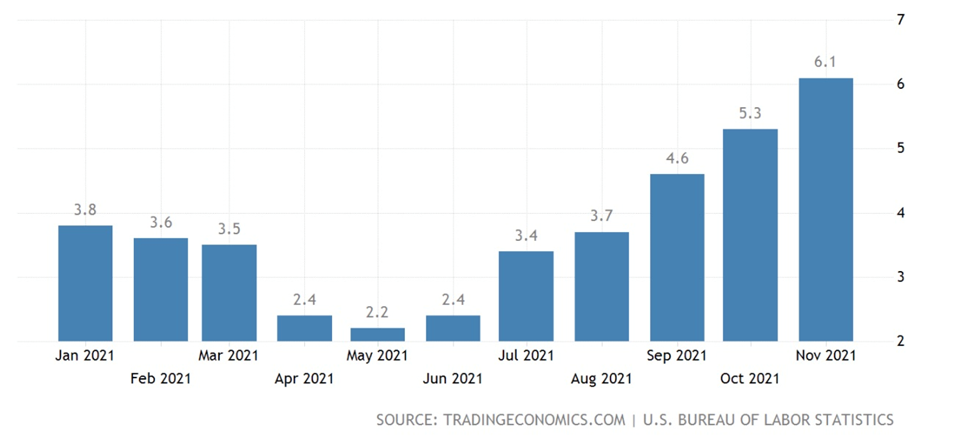

(High natural gas prices are impacting food prices. Food inflation is being driven by record-high fertilizer prices and climate change. Higher input prices are usually passed onto the buyer of meat, fruits and vegetables, for the rancher/ grower to preserve his profit margin.

The fertilizer market has been pummeled due to extreme weather, plant shutdowns and rising energy costs — in particular natural gas, the main feedstock for nitrogen fertilizer.

Modern farming simply cannot do without fertilizer; its higher cost must be borne by producers and so higher food prices are likely going to be “baked in” for several years. Everyone from ranchers to farmers, greenhouse growers and orchardists will be affected.)

Oil, gas & hybrids

What happened in Europe is important for resource investors to understand, because it could exemplify what is coming to North America, if we continue this mad dash to decarbonize without respecting our ongoing dependence on oil and gas.

NDTV lays it out nicely in an article titled, ‘Europe Sleepwalked Into an Energy Crisis That Could Last Years’.

Starting with the observation that its natural gas stockpiles are running dangerously low, the article points out that Europe was blindsided by an energy crunch because it was unprepared.

“The energy crisis hit the bloc when security of supply was not on the menu of EU policymakers,” says Maximo Miccinilli, head of energy and climate at consultants FleishmanHillard EU.

Europe’s natural gas production has been declining for years, leaving it reliant on imports. Yet even after an especially cold 2020-21 winter diminished natural gas supplies, Europe’s leaders didn’t lift a finger in response. NDTV explains:

Still, Europe’s leaders betrayed no alarm. On July 14, the European Commission unveiled the world’s most ambitious package to eliminate fossil fuels in a bid to avert the worst consequences of climate change. With their eyes trained on longer-term goals, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions at least 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels, the politicians did not sufficiently appreciate some of the potential pitfalls that lay immediately ahead on the road to decarbonization…

A recent bump in LNG imports from the U.S. has provided some relief, but it’s temporary at best. France needs to take several of its reactors offline for maintenance and repairs, resulting in a 30% reduction in nuclear capacity in early January, while Germany is moving ahead with plans to shut down all of its nuclear plants. With the two coldest months of winter still ahead, the fear is that Europe may run out of gas…

Traders are already preparing for the worst, with prices for gas delivered from spring through 2023 surging about 40% over the past month. Some say the crunch could last until 2025, when the next wave of LNG projects in the U.S. starts supplying the world market.

The world’s continued dependence on oil and gas is reflected in the importance of hybrid vehicles going forward. IHS Markit notes that hybrids are projected to outpace electric cars for years. This is in large part due to car buyers’ preference for the convenience of gasoline fuel, no need to charge the vehicle, and the lower cost of a hybrid compared to an all-electric.

We also see it in the crude oil import statistics of the United States and its allies.

Canada

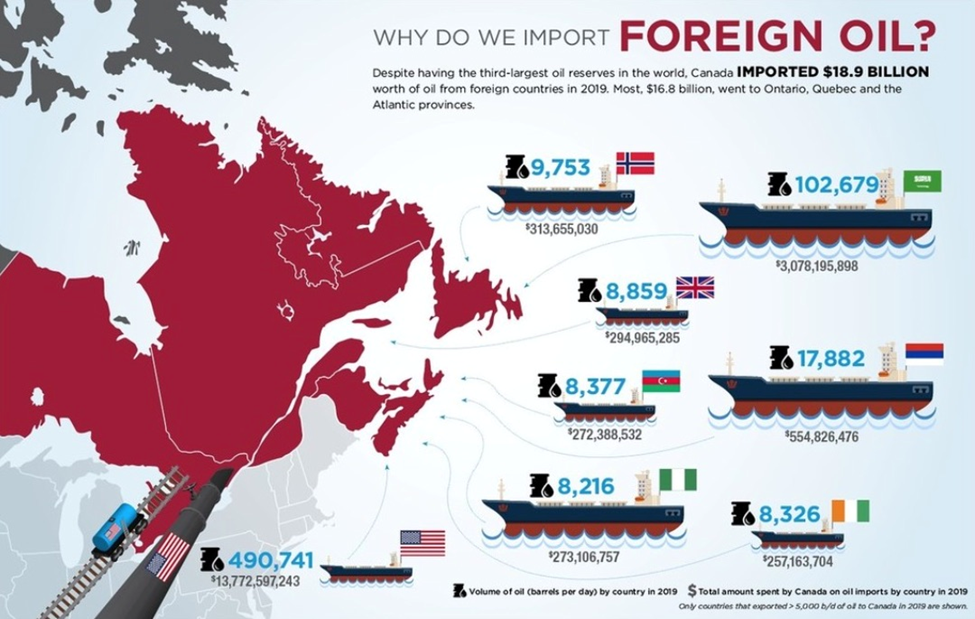

Despite having the world’s third-largest oil reserves, more than half of the oil used in Quebec and Atlantic Canada is imported from foreign sources including the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia, United Kingdom, Azerbaijan, Nigeria and Ivory Coast. In 2019, Canada spent $18.9 billion to import more than 660,000 barrels of oil, according to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP).

United States

For decades the United States imported more oil than it exported. It wasn’t until 2019 that US net imports of crude oil and finished products flipped from negative to positive, making the country energy-independent. That year, US oil production reached a record 12.2 million barrels per day. However in May 2020, the States was back to being a net oil importer, and it has oscillated since.

According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), in 2005, U.S. refineries relied heavily on foreign crude oil, importing a record volume of more than 10.1 million barrels per day (b/d). About 60% of the imported crude oil came from four countries: Canada, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela, and each was responsible for between 12% and 16% of total U.S. crude oil imports that year. By 2019, U.S. crude oil import trading patterns had changed significantly. In total, U.S. crude oil imports have fallen sharply, but imports from Canada have risen steadily to 3.8 million b/d, more than twice the imports from Canada in 2005.

The EIA chart below shows the United States gradually loosening the grip Saudi Arabia had on its oil imports — going from about 2.3 million barrels a day in 2005, to just 500,000 currently.

Exactly one year ago the US didn’t import any Saudi crude for the first time in 35 years. Bloomberg notes that 12 years prior, American refiners were routinely importing about 1 million barrels a day, the second-largest supplier to the U.S. after Canada and seen as a major security risk.

How did the US become energy-independent? It began hydraulic fracturing tight shale oil fields like the Permian, Eagle Ford, Marcellus and Bakken. Fracking may have pushed US oil production to a situation of energy independence, but it came at a huge environmental cost. Pumping a toxic mix of chemicals and proppants to liberate oil and gas from tightly packed rock layers requires huge amounts of water and has been known to seep into and pollute groundwater. Fracking also releases methane, a greenhouse gas 84 times more powerful than carbon dioxide, with research indicating the US oil and gas industry emits 13 million tonnes of methane annually.

In sum, the the holy grail of US energy independence has only been achieved by sacrificing the environment; air and water pollution not only costs money, but the health of people and animals living next to wells, and sometimes, their lives.

European Union

We’ve already mentioned the energy crisis in Europe brought about by prematurely closing nuclear and coal power plants, leaving the continent dependent on Russian natural gas.

In 2019 the EU produced 39% of its own energy, and imported 61%. According to Eurostat, petroleum products comprise the majority of available energy sources (36% crude oil, 22% natural gas), with renewables representing 15% of the total, and nuclear and solid fossil fuels both 13%.

The Canadian Energy Centre recently put out a very interesting paper documenting the EU’s dependence on totalitarian regimes for its energy fuels. Since 2005, the bloc has imported €286 billion form tyrannies and aristocracies, with Russia being the largest source of natural gas for the past 15 years.

The fact sheet examined NG imports from within and outside the European Union from Not Free, Partly Free, and Free countries between 2005 and 2019.

Germany is one the world’s largest natural gas importers. Data from Rystad Energy shows that in 2019, the country shipped in 55.5 billion cubic meters of gas from Russia, 27 bcm from Norway and 23.4 bcm from the Netherlands.

So much for Germany’s “energiewende” (energy transition).

What’s wrong with importing gas from Russia? The report notes that Russia has a history of interrupting natural gas flows for political gain:

This ever-growing dependence on Russia makes the EU potentially vulnerable to natural gas supply disruptions that could result from geo-political events, such as Russian meddling in the former Soviet Bloc countries. In the past, Russia has punished European countries that were selling Russian gas to Ukraine by cutting off natural gas being delivered through both Nord Stream and an existing pipeline to the Ukraine.

Other highlights from the report:

- Of the over €286 billion worth of natural gas imported by the EU from Not Free countries between 2005 and 2019, almost €165.3 billion worth, or nearly 58%, came from Russia; over €89.1 billion worth, or 31.1%, came from Algeria.

- Of the €16.4 billion worth of natural gas that the EU imported from Not Free countries in 2019, nearly €16.3 billion worth, or 99%, was imported from just three countries — Russia, Algeria, and Libya (see Figure 2b).

- Of the €16.4 billion worth of natural gas that the EU imported from Not Free countries in 2019, Italy, Spain, Hungary, Greece, and Slovakia alone imported over €14.8 billion from tyrannies and autocracies. Italy imported the most at nearly €9.3 billion or 56%.

- The EU and Turkey are heavily reliant on Russia for natural gas: 77% of natural gas exports from Russia’s majority state-owned Gazprom go to the EU. Germany used the most gas at 57 bcm followed by Italy at just over 22 bcm.

- For at least 15 years the EU has been heavily dependent on the natural gas shipped to it from autocracies and tyrannies, most notably Russia. With the planned completion of Gazprom’s Nord Stream 2, natural gas imports to the EU from Russia will only grow, making the EU even more vulnerable to Russian influence.

Australia

Australia’s fuel security is more precarious than most Australians probably realize. According to The Conversation, not only does the country not have the internationally mandated 90-day stockpile, but ongoing refinery closures put it on track to being 100% reliant on imported petroleum by 2030.

These refineries import around 83% of the crude oil they process, with the lion’s share coming from Asia (40%), followed by Africa at 18% and the Middle East at 17%.

The article notes that ongoing tensions in the South China Sea threaten a major supply route for Australian oil imports, the disruption of which would have consequences within days for our food supplies, medication stocks, and military capacity.

The vulnerability of Australia’s supply lines through Indonesia has also been documented. In 2014, Al Qaeda-aligned militants tried to hijack a Pakistani frigate and use it to target US Navy vessels in the Indian Ocean. The terrorist group reportedly urged jihadists to attack oil tankers in two maritime hot spots that supply Australia with up to 70% of its gasoline.

Japan

Japan’s relative isolation and its lack of natural resources made it the fifth-largest oil consumer and fourth-largest crude oil importer in 2019. The country has no international oil or natural gas pipelines, and therefore relies exclusively on tanker shipments of LNG and crude oil.

Before the 2011 earthquake/tsunami and partial meltdown at Fukushima, Japan was the world’s third largest nuclear power user, behind only the US and France. Prior to 2011, nuclear accounted for 13% of total energy needs, but the closure of all of Japan’s nuclear facilities for safety reasons and testing (some have re-opened) meant that by 2019, nuclear’s share had dropped to 3%.

According to the EIA, coal continues to command a significant share, 26%, of Japan’s total energy consumption, although natural gas is the preferred choice of fuel to replace nuclear.

In 2020, Japan’s largest crude oil importer was Saudi Arabia, and in 2019, the country consumed around 173 million tonnes of oil, with the largest amount coming from OPEC member states in the Middle East, according to Statista.

Conclusion

At the end of the day we have to ask, “Is going green really worth it?” To determine that, we first need to check whether mining all of the metals required for electrification and decarbonization is actually green. Chinese rare earths, Indonesian nickel, Congolese cobalt, are anything but.

For many years the United States and its allies bought their oil and gas from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. In recent years that dependence has eased.

At AOTH we’ve been warning for a decade the dangers of relying on fracking for anything but short term energy dependence. “The decline rate of shale gas wells is very steep. A year after coming on-stream production can drop to 20-40 percent of the original level. If the best prospects were developed first, and they were, subsequent drilling will take place on increasingly less favourable prospects.”

“My thesis is that the importance of shale gas has been grossly overstated; the U.S. has nowhere close to a 100-year supply. This myth has been perpetuated by self-interested industry, media and politicians. Their mantra is that exploiting shale gas resources will promote untold economic growth, new jobs and lead us toward energy independence.“ Bill Powers, author ‘Cold, Hungry and in the Dark: Exploding the Natural Gas Supply Myth’ in a Energy Report interview.

“Each year, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts production from the nation’s tight oil and gas plays — the hydrocarbon-rich formations targeted by the U.S. fracking industry. And each year, the EIA predicts rosy prospects for the nation’s oil and gas output. David Hughes carefully peered through the EIA’s forecasts, basin by basin, comparing the agency’s assumptions against the real-world drilling data that showed faltering productivity and fast declines from many shale wells. And he concluded that the EIA’s long-term oil and gas outlook suffers from an optimism bias so extreme that it borders on fibbing.” New Report Throws Doubt on Overly Optimistic Fracking Forecasts From U.S. Government,Clark Williams-Derry

But many Western nations remain under the thumb of oil oligarchs or sultans. Take Germany, which consumes the most natural gas of any EU country, the majority of which comes from Russia. 77% of natural gas exports from Russia’s Gazprom go to the EU. Of the over €286 billion worth of natural gas imported by the EU from Not Free countries between 2005 and 2019, almost €165.3 billion worth, or nearly 58%, came from Russia.

In a world that still runs on oil, how free are Western nations, when they depend on the good graces of places like Russia, Algeria and Saudi Arabia, for their oil and gas?

How free is the West when it must go cap and hand to China, for the new electrification/ decarbonization metals?

Consider: China rules the electric vehicle supply chain. It is also a major player in renewable energy markets (solar & wind), and is building the most new nuclear power plants of any country.

In the rush to electrify/ decarbonize, is the West not just substituting one energy tyrant for another? The world’s largest consumer of commodities already has a monopoly on rare earths mining/ processing, produces the most lithium and cobalt, and dominates the graphite market.

China controls about 85% of global cobalt supply, including an offtake agreement with Glencore, the largest producer of the mineral.

Beijing also appears to be locking up nickel supply, through investments in the leading producer, Indonesia. China is working with Indonesia to develop a huge facility for developing battery-grade nickel.

According to the International Energy Agency, China processes about 90% of the world’s rare earth elements, along with 50 to 70% of lithium and cobalt.

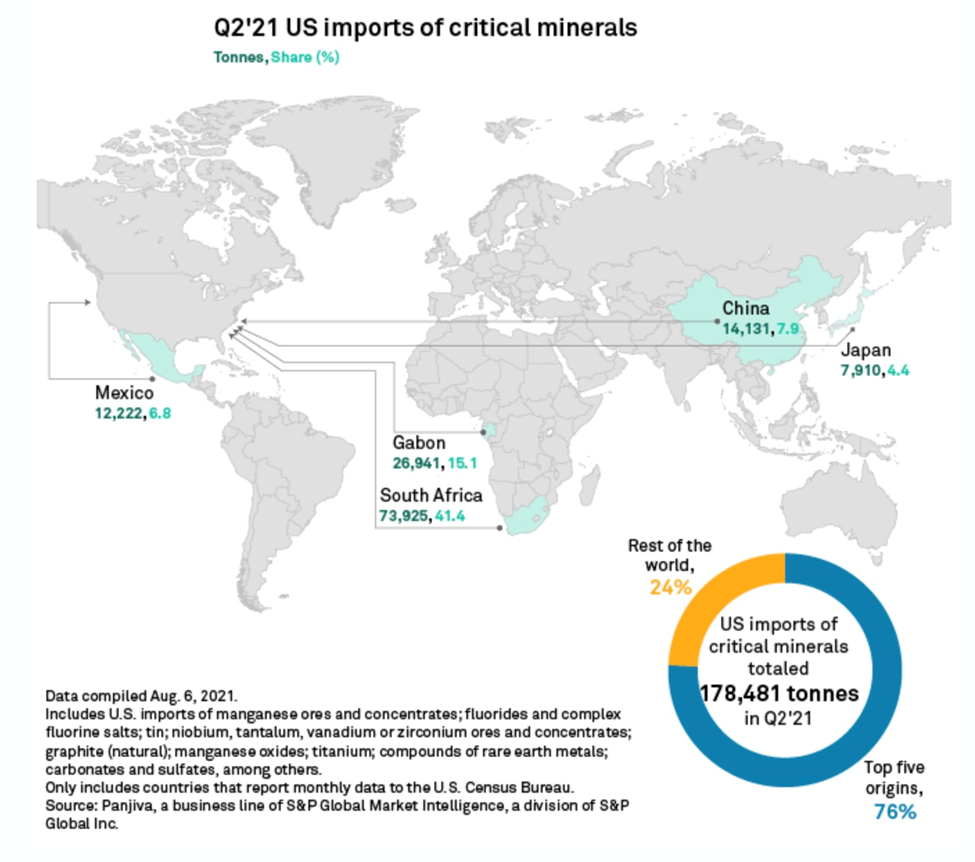

The United States is 100% import-reliant on 13 of the 35 critical minerals the Department of the Interior has classified. They include manganese, graphite and rare earths. According to Market Intelligence data, the majority of critical minerals imported during the second quarter of 2021 came from South Africa (41.4%), with 7.9% shipped from China.

“We are dependent upon different countries, most notably China, for a number of our critical mineral resources,” S&P Global quotes Abigail Wulf, director of critical minerals strategy for Securing America’s Future Energy, a group advocating for greater US energy independence.

As China’s fist tightens on the mining of critical and green economy metals, Western politicians like Justin Trudeau, Joe Biden and Germany’s (ex-Chancellor) Angela Merkel have supported green energy/ transportation at the expense of fossil fuels.

Germany is phasing out nuclear and coal-fired plants but has not yet achieved the renewable power capacity needed to replace shuttered power-generation facilities.

It needs Russian natural gas just to keep the lights on and buildings heated. The recent decision to shutter three of its six nuclear power plants in the middle of winter is foolish and cruel. What of the millions of Germans, and other Europeans unable to afford a quadrupling of power bills, that are being left in the dark to freeze?

Think about it. Without a workable plan to transition from fossil fuels to renewables, one that does not involve natural gas shipments from Russia, burning coal, or buying petroleum products from Saudi Arabia (like Canada and Japan), and without a concerted push to mine and explore for minerals within its own borders, the West is literally giving away its energy security to two countries: China and Russia.

They must be laughing at our stupidity.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.