Inequality, inflation and gold

2022.03.19

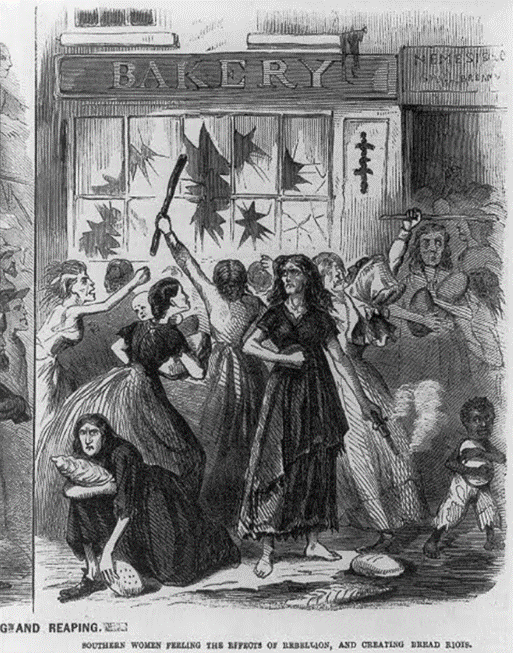

Food inflation has historically been the catalyst for many popular uprisings, from the French Revolution to the (US) Flour Riot of 1837, the Richmond Bread Riot of 1863, and more recently, the Arab Spring. When people can’t afford to eat, when work has dried up and they can no longer feed their families, when housing represents more than two-thirds of income, a point of reckoning is reached.

The covid-19 pandemic pushed nearly 300 million people to the brink of starvation. Just when it appeared to be letting up, we were hit with a new crisis, the war in Ukraine. The conflict is certain to increase the ranks of the impoverished, not only in Ukraine where cities are being bombed and residents are fleeing with nothing but a toothbrush and their ID, but in countries that depend on Russia’s and Ukraine’s food exports (farmers don’t feel safe to plant in the Ukraine and Russia’s economy is being pummeled by Western sanctions).

Among the countries most likely to be impacted by wheat supply disruptions are Egypt, Turkey and Iraq. The Middle East has already been hit with a wave of uprisings partly caused by food price inflation, could an Arab Spring 2.0 be far behind? We also need to keep our eye on Russia. The ruble has lost more than 64% to the US dollar year to date, a record low, and Western sanctions are starting to bite. The war isn’t the fault of ordinary Russians, many of whom are going to become food insecure if economic conditions continue to worsen.

People are getting mad, and it isn’t only rising food prices.

Inflation in the United States is at levels last seen in 1982, and it’s not much better in Canada. But in the early ‘80s, at least you could afford to buy a house, even with interest rates in the double digits. For many North Americans, that is no longer the case. Home inflation is running rampant, and rents are higher than ever.

The impacts of droughts and floods, climate change and covid-19, are all being passed up the food supply chain to the consumer, who is seeing double-digit inflation in some products such as meat.

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia, a major oil and gas producer, and the world’s largest exporter of wheat, is adding to higher grocery bills, and record gasoline prices. As extreme weather continues to hit us from both sides of the continent, we best get used to it.

Climate change has a major impact on agricultural commodities that are affected by droughts and flooding. Paraguay was hit by a drought late last year that has badly damaged crop yields and caused navigation problems in the Paraguay-Panama waterway, pushing up the costs of transporting grains for export. Neighboring Argentina, the world’s top exporter of processed soy, is also facing the risk of drought diminishing soy and corn harvests. Dry conditions often cause forest fires that can ruin crops and kill livestock.

Flooding and saltwater intrusion are also threats to farming, especially in coastal areas vulnerable to rising sea levels. The latest projections by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have levels increasing by a foot by 2050, threatening to inundate cities including Miami and New York.

Last fall’s “atmospheric rivers” in southern British Columbia caused nearly half a billion dollars in flood damage to one of the province’s most important regions for fruits, vegetables, eggs and dairy products. The B.C. Agriculture Council says the freak weather events will cost farmers “hundreds of millions of dollars”. The B.C. Dairy Association estimates 500 cattle died from Fraser Valley flooding.

Higher food, energy and housing prices tie into a growing crisis of affordability. Wages haven’t kept up with historically high inflation. As inflation eats away disposable income, nearly two-thirds of Americans (64%) are living paycheck to paycheck.

The US Federal Reserve on Wednesday raised interest rates by a quarter percentage point for the first time since 2018. The rate hike is expected to cool demand for goods and services which has driven inflation to a 40-year high of 7.9%. We remain skeptical.

The last time the Fed tried to raise rates it only got to 2% before it crashed the stock market and rates began falling again. Higher US Treasury yields are already throttling the US economy and growth is set to slow sharply this year. Zero Hedge reports rising rates are causing lending standards to tighten and banks are becoming less willing to extend consumer loans. Consumption will face growing headwinds as credit is squeezed.

Remember, the American consumer makes up nearly 70% of US GDP. If consumer spending slows it will definitely put a damper on economic growth.

The war in Ukraine and Western sanctions against Russia are driving up the costs of energy and agricultural/ metal commodities. The conflict threatens to raise the costs of transporting and manufacturing a range of goods, while further disrupting global shipping networks.

All of this has complicated the Fed’s efforts to tame inflation through a series of rate hikes this year and next. The Wall Street Journal says the demand for workers outstripping supply, combined with “inflation psychology” making employees push for better wages in anticipation of higher inflation, threaten to ignite an inflationary spiral, where workers face higher prices and demand more pay, leading businesses to continue raising prices.

Covid exposed the weaknesses in our supply chains. The war has revealed how some of the countries most vulnerable to food price hikes, are dependent on the Russian-Ukrainian bread basket.

Globalization brought with it the mentality that all countries are free traders, and friends. But globalization doesn’t work very well when commodity exporting nations are fighting each other.

I see the war in Ukraine, covid, supply chain interruptions, inflation and climate change coalescing into a perfect storm of unaffordability that could eventually erupt into mass social unrest.

When people can’t afford life’s basic necessities and prices keep rising, to quote Karl Marx, “proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.”

In the first article of three, we discussed how worsening inequality is impacting the capacity of people to feed themselves. Food insecurity has doubled in the past two years, and the World Food Program estimates 45 million people are on the brink of famine.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has only added to the misery. Not only has the war resulted in millions of displaced Ukrainians seeking refuge in neighboring countries, it has interrupted exports of key agricultural commodities. Ukraine and Russia account for 25% of global wheat supplies but shipments from both countries have all but dried up. The war could be the tipping point of a full-blown global food crisis.

Our second article considered the impacts of climate change in driving the prices of goods ever higher. Droughts are impacting food production in Canada and the United States, lowering crop yields, and causing ranchers to cull part of their herds. Stubbornly high natural gas prices are being reflected in record-high fertilizer prices. Other farm inputs like feed and barley are going through the roof.

Availability of fresh water is also a growing concern.

Last summer the federal government declared a water shortage on the Colorado for the first time, triggering mandatory water consumption cuts. Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the US, last August hit its lowest level since it was filled in the 1930s. Lake Powell, also fed by the Colorado River, also hit a record low and last summer was just 32% full.

If too much groundwater is pumped out from coastal aquifers, saltwater may flow into them causing contamination. Many coastal aquifers — the Biscayne Aquifer near Miami and the New Jersey Coastal Plain aquifer for example — have problems with saltwater intrusion. The phenomenon can also be caused by rising sea levels and storm surges.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), via Reuters, the seas lapping US coasts are expected to rise at a faster pace than in the past 100 years; a one-foot rise by 2050 threatens coastal cities including New York, Boston and Miami.

Salt water from the Bay of Bangladesh has penetrated over 100 kilometers inland, due to sea levels rising higher than elsewhere, thereby increasing the risk of water contamination and hypertension caused by drinking high-salinity water. High river and soil salinity in Bangladesh is also predicted to reduce rice crop yields, affect the productivity of fisheries, crack road surfaces, and increase poverty.

In this, our final instalment of a three-part series, we take a deep dive into worsening inequality, globally and especially in the United States.

Inequality

Oxfam recently calculated that 26 of the richest people have the same amount of wealth as 3.8 billion in the world’s bottom half. Inequality is even starker in the United States, where the three wealthiest individuals have as much as the bottom 160 million.

The Guardian observes that right-wing political movements and the rise of populism over the last few years have their roots in the financial crisis of 2008-09. Not only did the Great Recession result in significant job losses and millions of Americans losing their homes from the sub-prime mortgage crisis, it also “stripped the sheen off global capitalism”:

In the US alone, the great recession erased about $8tn in household stock-market wealth and $6tn in home value. From 2003 to 2013, inflation-adjusted net wealth for a typical household fell 36%, from $87,992 to $56,335, while the net worth of wealthy households rose by 14%. Workers without college degrees and low-income Americans were especially hard hit.

Also consider: the average US household is indebted to the tune of $150,000, and each person owes $99,000.

In 2018 the three highest-paid chief executives in the United States earned more than the output of several countries. Contrast this to the average Johnny Paycheck.

A December 2021 World Economic Forum report found the pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities. Among its conclusions, the report says:

- The richest 10% of the global population currently take home 52% of the income. The poorest half earn just 8%.

- On average, an individual from the top 10% will earn $122,100, but an individual from the bottom half will earn just $3,920.

- The poorest half of the global population owns just 2% of global wealth, while the richest 10% own 76%.

- Over the last two decades, the average income gap between the top 10% and bottom 50% of individuals within countries has almost doubled.

- 2020 marked the steepest increase in the global billionaires’ share of wealth on record.

As regular people were laid off or had their hours cut, due to government-mandated business closures, or capacity limits, some of North America’s largest companies were taking advantage of generous government covid benefits. And as the stock market soared due to low interest rates and massive government stimulus, throughout the pandemic, a lot of businesses were cashing in, along with their CEOs, whose compensation is largely driven by stock performance.

Data from the Economic Policy Institute quoted by Forbes showed that in 2020, the average CEO’s compensation jumped 16%. This compares to average worker compensation, which grew only 1.8%.

Canada’s top CEOs also had a very good year in spite of the pandemic. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives examined the 100 highest-paid CEOs at publicly traded Canada-based companies for 2020. It found that their average annual compensation totaled $10.9 million — $95,000 more than their average pay in pre-pandemic 2019.

As the global health crisis ebbs and businesses return to something approaching normal, the cash keeps flowing to C-suite occupants — in particular those having anything to do with vaccines.

One example is Moderna CEO Stephane Bancel. Earlier this month the company’s board of directors approved a golden parachute for Bancel worth more than US$926 million. The vaccine maker’s revenues reportedly went from $803 million in 2020 to $18.5 billion last year, having delivered more than 807 million doses of its mRNA shot. This year’s sales are projected at $22 billion.

Taken to extremes, inequality causes social upheaval, and often, violent revolution. China, Russia and France are among the countries that experienced bloody worker or peasant-led insurrections.

We only have to look at Chile to see this dynamic in action. In 2019, over a million people turned out to show their frustration at widening inequality and what many saw as the government’s attack on the poor. The trigger was a seemingly innocuous hike in transit fares.

A state of emergency was declared and armed forces mobilized on the streets of Santiago for the first time in nearly 30 years. Chile, the world’s largest producer of copper and with the most lithium reserves, used to be considered among the most stable and business-friendly Latin American nations.

But many Chileans are poor. The country leads the OECD’s 30 wealthiest nations in inequality, followed by Mexico, Turkey and the US. The richest 1% earns one-third of the wealth. Half of Chile’s workers earn less than 400,000 pesos per month (roughly US$550).

The Gini coefficient is often used as a gauge of economic inequality. In 2018, households in the top fifth of earners, those with incomes about $130,000, pulled in 52% of all US income — greater than the lower four-fifths combined, according to Census Bureau data.

By comparison, in 1968, the top 20% of income earners brought in just 43% of total US income, compared to 56% for the lower four quintiles.

Updated to 2022, the US Gini coefficient has grown to 0.484, the highest it’s been in 50 years. The country has the highest Gini coefficient among G7 nations, with the top 1% of earners making about 40 times the bottom 90%.

Watch this video by CNBC to understand five key drivers of inequality that are widening the gap between the rich and the poor:

- The digital revolution, which creates huge opportunities for those with the skills and education to take advantage, but eliminates “middle skill” jobs like clerical and manufacturing positions that once produced middle-class incomes for those without college degrees;

- Globalization, involving competition from economies like China, combined with reduced trade barriers, have further reduced prospects for those without advanced skills. This was dramatically accelerated by China’s acceptance into the World Trade Organization in 2001. Around one in three American manufacturing jobs existent in 2000, were gone by the end of the Great Recession in 2010;

- Superstar tech firms like Apple, Amazon, Uber and Facebook are market disruptors that generate huge global revenues. Their CEOs, like Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, the richest man in the world, make obscene packets, dramatically accelerating the CEO-to-worker compensation ratio;

- The percentage of the workforce represented by labor unions has halved since the 1980s, shrinking their power to extract concessions from management. The government has not increased the minimum wage to keep pace with inflation.

- Certain government decisions have rewarded the wealthy, such as the $1.5 trillion Trump administration tax cuts in 2017, and college admissions procedures that open doors to their children above others.

Taking it to the streets

Between 1865 and 1898 the US economy grew at the fastest rate in its history with real wages, wealth, GDP and capital formation all increasing rapidly.

Yet in 1880, 11 million of the nation’s 12 million families earned less than $1,200 per year — their average annual income was $380, well below the poverty line.

Mark Twain called the late nineteenth century the “Gilded Age”, meaning that the period was golden on the surface but underneath the thin veneer was a cesspool of banksterism, greed and graft, shady business practices, scandal-plagued politics and overt displays of upper-class materialism.

If we stop looking in the rear-view mirror and fast forward to the future we’re struck by the many similarities to today’s present conditions.

We have at least equaled or exceeded the extremes of inequality achieved by our late 19th century predecessors. The comparisons between Twain’s Gilded Age and our present circumstances are numerous: crony capitalism and government, the mortgage and banking crisis, big business tax breaks, the creation of complex financial instruments, small factories and workshops closing, unemployment exploding, unemployed workers demonstrating, corruption, ostentatious spending, wage depression, massive urbanization and the use of police, armed force, to break up demonstrations.

In fact, it may surprise readers to learn that US history is littered with examples of civil unrest. Americans have taken to the streets and rioted over a seemingly endless list of grievances, including racism, sexism, workers’ rights, immigration, housing, the draft, food, beer, wars, and most recently, Black Lives Matter — a combination of perceived racial injustice and police brutality/ racial profiling.

We all know that race is a defining cleavage of American society dating back to the days of slavery. We would therefore expect a lot of civil unrest to be racially motivated. More surprising is how many of these protests were over food, worker’s rights and global capitalism. Examples include:

Flour Riot, 1837 — In New York City, hungry workers plundered storerooms filled with sacks of hoarded flour, after commodity prices skyrocketed over the winter of 1836-7, fueled by foreign investment and two successive years of wheat crop failures.

Richmond Bread Riot, 1863 — Food deprivation during the American Civil War was the cause of this, the largest civil disturbance in the Confederacy during the war, in Richmond, Virginia, on April 2, 1863. A Union blockade of Confederate ports prevented food from being imported from other countries. Also, less food was being grown because of the war. As food became scarcer, prices jumped. Encyclopedia Britannica describes what happened on April 2:

Led by Mary Jackson, a mother of four, and Minerva Meredith, whom Varina Davis (the wife of President Davis) described as “tall, daring, Amazonian-looking,” the crowd of more than 100 women armed with axes, knives, and other weapons took their grievances to [Gov. John] Letcher on April 2. Letcher listened, but his words failed to pacify the crowd, and the women began marching toward government food storehouses, crying, “Bread! Bread!” and “Bread or blood!” As the group marched, they were joined by additional people brandishing weapons. The original group swelled to hundreds, perhaps thousands, of rioters. The governor called out the public guard, but its forces could not stop the crowd, which broke into government storehouses and nearby businesses, taking whatever they could get their hands on.

Draft Riot, 1863 — The same year, four days of violence erupted in New York City, resulting from worker discontent surrounding the inequities of conscription. Low-paid workers in the North were particularly antagonized by a federal provision allowing more affluent draftees to buy their way out of the Federal Army. Property damage from the July 11, 1863 riot totaled $1.5 million, an enormous sum at the time.

Haymarket Riot, 1866 — The Haymarket Riot was a violent confrontation between police and labor protesters over workers’ rights. On May 3 in Chicago, one person was killed and several injured during a union action at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, part of a national campaign to secure an eight-your workday. The following day, labor leaders called a mass meeting to protest police brutality. At some point a bomb was thrown and police responded with random gunfire. Seven police officers were killed and 60 others were wounded. Civilian casualties amounted to four to eight dead and 30-40 injured.

Seattle General Strike, 1919 — More than 65,00 workers paralyzed the city during a five-day work stoppage lasting from Feb 6-11. Dissatisfied workers from a number of unions struck for higher wages after two years of wage control during World War I. Historians blame the strike on Bolsheviks and other radicals attempting to subvert American institutions. In Seattle there was a 400% increase in union membership from 1915 to 1918.

Ford Hunger March, 1932 — On March 7, during the depths of the Depression, unemployed autoworkers marched from Detroit to Dearborn, Michigan. In a confrontation with police, four workers were shot dead and one later died of his injuries. The march was supported by the Communist Party USA, and part of a chain of events that resulted in unionizing the US auto industry.

Levittown Gas Riot, 1979 — Thousands rioted in Levittown, Pennsylvania over increases to gasoline prices, resulting in 198 arrests, with 44 police and 200 rioters injured. Gas stations were damaged and cars set on fire.

WTO Meeting, 1999 — Also referred to as the Battle of Seattle, the 1999 Seattle WTO protests were a series of protests surrounding the World Trade Organization’s Ministerial Conference, held at the Washington State Convention and Trade Center. Negotiations were quickly overshadowed by massive street protests involving at least 40,000 protesters, more than any previous meeting associated with globalization. The four-day event resulted in the resignation of Seattle’s police chief and 157 arrests. Many television viewers remember the Battle of Seattle for the images of police pepper-spraying protesters and of using tear gas to disperse the crowd.

Occupy Wall Street, 2011 — The movement against economic inequality, greed, corruption and the undue influence of corporations on government, was initiated by Canadian anti-consumerist magazine AdBusters. First centered around New York City’s financial district, Occupy Wall Street then turned to banks, corporate headquarters, board meetings, foreclosed homes and college/ university campuses. The OWS slogan “We are the 99%” refers to income inequality between the wealthiest 1% and the rest of the US population.

Conclusion

The war in Ukraine is accelerating a global food crisis that is reverberating across the world, in countries that literally depend on Russia and Ukraine for putting food on the table. (remember, together they account for 25% of global wheat shipments)

It is uncertain how long disruptions in the food chain will last. We do know that hardship will result in countries most dependent on them for food imports, including food insecurity, hunger, starvation and death.

Accompanying the unfolding global food crisis is a crisis of unaffordability. Consumers everywhere are getting squeezed on housing costs, fuel, persistent inflation and a loss of purchasing power. Climate change is making it more difficult to irrigate fields and pastures. Droughts and floods are ruining crops or reducing yields, forcing some farmers into bankruptcy. Many grocery items have exploded in price due to covid-related supply disruptions, bad weather, the Russo-Ukrainian war, or a combination of the three.

It all adds up to a perfect storm that, if nothing changes, will imo lead to a breaking point, when people have nothing left to lose and revolution is seen as the only means of forcing social and economic change.

This week the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates by 0.25%, the first increase since December 2018, to address 40-year high inflation. Clearly it won’t be enough and the central bank will be pressured over the coming months to add more rate hikes. Officials are targeting rate rises at each of the remaining six Fed meetings in 2022. That would bring the federal funds rate to 1.75% by the end of the year, if the six additional increases are @ 0.25%, or 3.25% or they raise by 50 basis points each meeting (+0.5%).

However, the Fed is severely constrained in how much further it can lift rates, due to the crushing amount of debt — including government, corporate and household. The national debt currently sits at $30.3 trillion. Each interest rate rise will mean much higher interest payments, which are already at nearly $600 billion.

There is a line of thinking out there that the Powell Fed’s intention is to go hostile, that the only way it is able to fight the level of inflation that has permeated the economy, is to “crash the market”. If you think about it, this is precisely what Paul Volcker’s Fed did in the early 1980s and it is what Fed Chair Jerome Powell tried to do, but failed to, in 2018, beyond a three-month stock market pullback.

History tells us that previous Fed rate hikes to deal with uncomfortably high inflation resulted in recessions.

During the 1970s consumer price inflation averaged 7%. To tackle it, then-Fed chair Paul Volcker dramatically raised interest rates. From 11.2% in 1979, Volcker and his board of governors through a series of rate hikes increased the Federal Funds Rate to 20% in June 1981. This led to a rise in the prime rate to 21.5%, which was the tipping point for the recession to follow, lasting two years.

Let’s remember what happened when the Fed tried this in 2018. They only got to 2% when the stock market tanked, prompting them to reverse course, and re-instate low interest rates.

We predict the same thing will happen this time. When the markets break under the pressure of too-high interest rates, the Fed will have no choice but to slam the brakes on rate hikes and begin retracing.

When this happens, probably in 2023 but possibly earlier, get ready for the next big move up for gold.

Gold has performed remarkably well in recent days despite the rate hike on Wednesday which was widely expected to dent’s bullion’s appeal among safe-haven investors looking for a yield amid poor stock market performance associated with the war in Ukraine.

Spot gold indeed pulled back about $45 between Monday and Wednesday, however on Thursday it re-gained $10 and last traded in New York at $1,938.40/oz, as of this writing. The price was helped by a lower US dollar and a drop in the benchmark US Treasury yield. Year to date, gold has advanced a respectable 7.5%.

One of the more interesting questions concerning gold right now is whether the Russian central bank could sell some of its substantial gold reserves to help shore up the ruble, which has plunged against the US dollar as a result of Western sanctions. Since the mid-2000s the Bank of Russia has expanded its gold pile nearly six-fold; it is now valued at about $140 billion.

Renowned gold expert Jeffrey Christian was quoted saying Moscow could look to India or China to sell gold to, or secure loans using it. Russia could also sell via the Shanghai Gold Exchange where it has commercial banks as members.

If Russia get desperate it could sell gold domestically to buy rubles. “If things get worse, you could basically re-anchor to a pile of gold,” Credit Suisse Group AG strategist Zoltan Pozsar said on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast. “You need an anchor in situations like this.”

Intriguing to think that the war between Russia and Ukraine could result in Russia ending up with a de facto gold standard.

Other authoritarian regimes have turned to gold when backed into a corner. Libya’s Moammar Qaddafi sold part of Libya’s reserves to pay for troops during an uprising. Former Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez repatriated much of the country’s gold.

The current president, Nicolas Maduro, tried unsuccessfully to access gold stored at the Bank of England after the UK recognized opposition leader Juan Guiado as president. In 2019 we wrote about a mysterious Russian Boeing 777 that landed in Caracas intending to transport 20 tons of gold stored in the central bank, likely to Russia or the Middle East. Though Maduro later canceled the shipment, it showed the importance of gold in a crisis. What do you do when your country is falling apart? You find bullion to sell, or use as a bargaining chip.

Meanwhile inflation is running rampant throughout much of the developed world, and gold is a tried and true hedge against the rising prices of goods and services denominated in fiat currencies.

Although gold offers neither a yield (bonds, GICs) nor a dividend (stocks and mutual funds), it is considered a smart investment when inflation diminishes an investor’s principal or erodes the purchasing power of a currency.

US inflation last clocked in at 7.9%, Canadian prices are rising at a rate of 5.7%, and in the UK, inflation is running at 5.4%. All three are at multi-decade highs, and this was before the war in Ukraine jacked up the prices of a number of key agricultural commodities (including wheat) along with oil, natural gas and minerals, particularly nickel and palladium of which Russia produces in large quantities.

The next inflation readings in March are all but guaranteed to be higher.

The Producer Price Index, a more accurate index of inflation because it reflects actual producer prices, is at 10%. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, prices for final demand goods jumped 2.4% in February, the largest advance since data was first collected in 2009. Two-thirds of the increase was traced to an 8.2% rise in the index for final demand energy. (PPI for final demand measures the average change in prices received by domestic producers of goods and services)

Assuming the Fed follows through on 0.25% interest rate hikes at each of its next six meetings, we are looking at a federal funds rate (the overnight lending rate) of 1.75%. Even if the Fed raised the rate 0.50% at each of their remaining meetings this year the resulting 3.25% still isn’t enough to combat CPI inflation of 7.9%, or Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation of 6.1% — the Fed’s preferred inflation index.

After subtracting the current yield of the 10-year Treasury from inflation you are left with a negative real yield of -4%. And remember real inflation, if measured the old way, is in double digits.

Negative real rates are a strong buy signal for gold.

When are people going to realize locking your money away for a decade in a 10-year Treasury note does not make any sense?

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.