If it can’t be grown it must be mined – Part 2

2022.04.24

In our last article, ‘If it can’t be grown it must be mined’ (link) we looked at how mining is essential for maintaining our modern way of life, dramatically illustrated by what would happen if the world suddenly stopped extracting minerals.

In this second part, we turn to the world’s three most important staple foods— rice, corn and wheat — all of which have soared in price over the past year due to the trifecta of climate change, the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

Food inflation

The war has accelerated a global food crisis that is reverberating across the world, in countries that literally depend on the region for putting food on the table.

The conflict has choked off over 25% of the world’s supply of grain, putting the market on track for the “sharpest shock” since the 1970s. Higher prices are speeding up food inflation and raising concerns for countries reliant on foreign supply.

In early April, Global News reported a backlog of grain-filled railcars on Ukraine’s western border, after Russia blocked off Black Sea ports. The cost of delivering grain to the Romanian port of Constanta has more than quadrupled, from about $40 per tonne before the war to $133-166/t. Ukraine was the world’s fourth-largest grain exporter in 2020-21.

Gallup, the polling firm, provided data indicating which countries are most likely to suffer from a wheat supply disruption. Topping the list is Turkey, which received 75% of its wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine in 2019. Second is Egypt, which imported 70% of its grain from Russia and Ukraine in 2019. Note that Russia’s low wheat harvest in 2010 due to drought was a major factor in the Arab Spring that broke out in Egypt.

Adding to current supply concerns for agricultural commodities, some countries are hoarding stockpiles, while others are restricting exports. Hungary banned grain exports and Serbia halted exports of wheat, corn, flour and cooking oil. Indonesia tightened curbs on exports of palm oil, used in a range of food products including biscuits, margarine, laundry detergents and chocolate. Argentina announced plans to increase control over local farm goods by suspending soybean meal and oil for export, causing soy meal futures to jump.

Countries that could normally fill the void are themselves having production problems. A drought in Brazil, a major supplier of corn and soybeans, has ruined crops, while in Canada and the US, a prolonged period of hot and dry weather in 2021 also wilted fields.

Globally, wheat farmers are already running at full tilt and most northern hemisphere nations have limited ability to grow more because the crop has already been planted.

Hardship will fall on countries most dependent on Russia and Ukraine for food imports. The number of people facing starvation worldwide spiked from 80 million to 276 million before the invasion, due mostly to covid lockdowns. That figure is set to rise again.

Fertilizer is an underestimated aspect of the food supply chain that modern farming simply cannot do without; its higher cost must be borne by producers and so higher food prices are likely going to be “baked in the cake” for several years.

Retail fertilizer prices tracked by data provider DTN for the second week of April showed all eight major fertilizers had higher prices than in March. Phosphorous fertilizer DAP hit a record $1,047 per ton.

Farmers are having to reduce their plantings due to urea shortages. Any reduction in nitrogen, which must be applied annually, will immediately impact crop yields, severely impacting food staples like corn and wheat.

For most growers, they have no choice but to pass on the added costs to their customers.

Data from the United Nations shows world food prices reached an all-time high in February — a year on year increase of 20.7% — driven by an 8.5% increase in the FAO Vegetable Oils Price Index, which also hit a new pinnacle.

The Food Price Index continues to climb, registering 157.48 in March, which is 36.5% higher than a year ago.

United States food inflation rose 8.8% in March, the largest increase in food prices since 1981. Bank of America analysts quoted by Fortune say it’s only going to get worse; they expect US food inflation to hit 9% by the end of the year, as sticker shock from the Russia-Ukraine war hits American grocery stores.

Staple foods

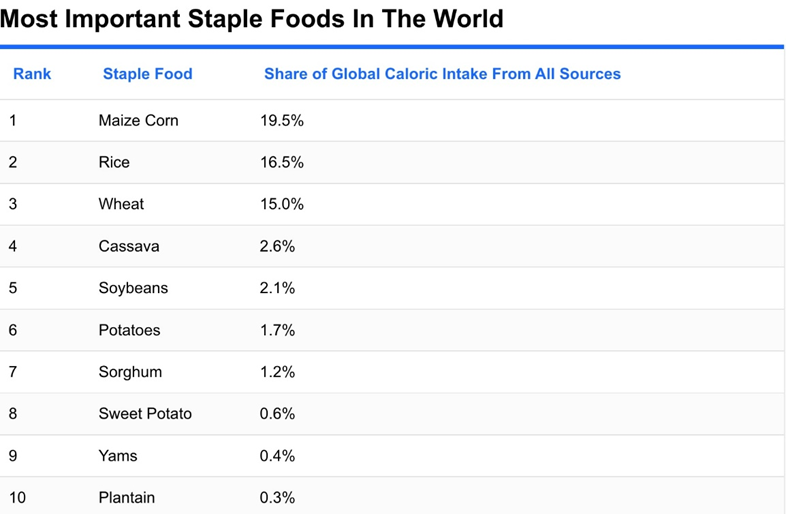

The majority of staple foods come from just three grains: corn, rice and wheat. Together they make up 51% of the world’s caloric intake.

Corn

Supplying 19.5% of the world’s calories, corn is a major source of food in Africa, Europe and the United States. Corn is not only boiled and eaten “on the cob”, but processed into flour, high-fructose corn syrup, whiskey and cooking oil.

On Monday the price of corn futures hit $8 a bushel, the highest since 2008, as traders factored in dwindling supplies. A drought across the US Midwest is partly responsible, but so is the war in Ukraine. According to Zero Hedge, The global outlook for corn supplies has plunged since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began in late February. The war-torn country supplies a fifth of the world’s corn and could experience a 50% decline in output this year.

The Biden administration’s recent decision to expand biofuel sales, to curb soaring gasoline prices, is exacerbating the problem. The ethanol industry competes with farmers for corn feedstock, making less available to the food industry, thus raising prices.

A new study by Penn State, published in ‘Agriculture Management’, found that, based on their climate modeling, rainfed corn yields will decline by up to 40 bushels per acre, compared to a 19-bushel decline for irrigated yields (US corn growers in 2021 produced a record yield of 177 bushels per acre).

Wheat

Archeologists believe wheat was the first domesticated crop, grown in ancient Mesopotamia, near modern-day Iraq. The US, China, Russia, India and France are the largest wheat producers. About 15% of the world’s calories come from wheat, which is usually dried and pulverized to make flour. In the Middle East and Africa wheat comprises as much as 35% of calories and a majority of it is imported, mostly from the Black Sea area.

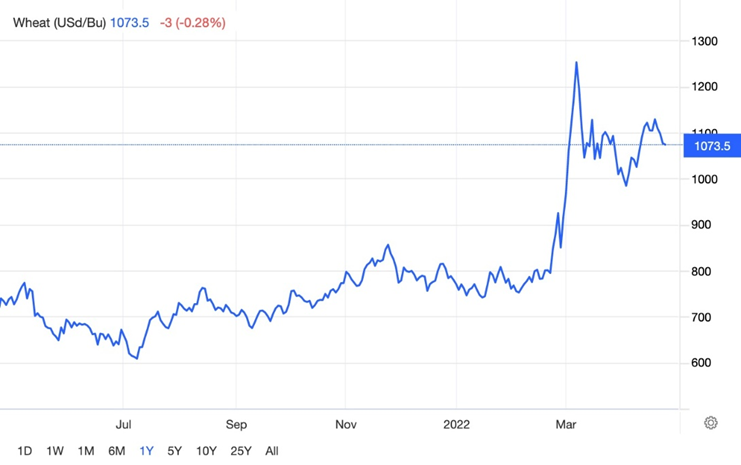

Grain stockpiles are poised to decline for a fifth straight year, due to a combination of higher shipping costs, energy inflation, extreme weather and labor shortages. World wheat prices soared 19.7% in March following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which disrupted Black Sea exports.

Wheat, like corn, is vulnerable to climate change. A 2019 study cited by Harvard University suggests that extreme and prolonged droughts could affect 60% of the world’s wheat production by the end of this century. That is quadruple the amount of wheat currently impacted by drought conditions.

Rice

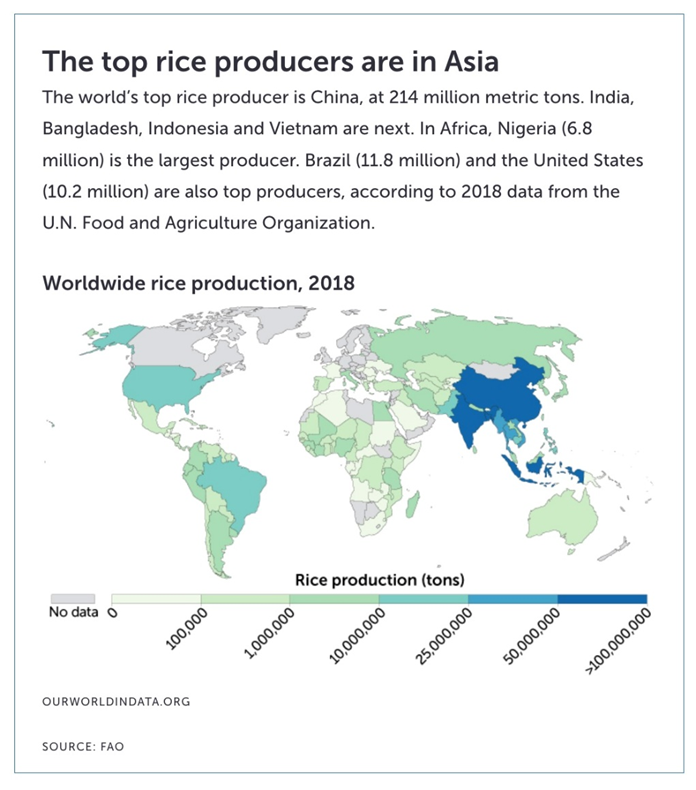

More than 1.6 billion people, just over the population of China, depend on rice for their daily nourishment. The fluffy grains make up 16.5% of global caloric intake. First domesticated in India and Southeast Asia, rice is now a staple food in Asia, Latin America and Africa.

Elevated fertilizer prices are taking their toll on rice farmers, many of whom must reduce the amount of nutrients to save costs, thereby threatening future harvests.

The International Rice Institute warns that harvests could plunge as much as 10% next season, equating to 36 million tons of rice, enough to feed half a billion people.

Science News reports that climate change’s floods and droughts are putting at risk the crop that feeds half the world — more than 3.5 billion people get 20% or more of their calories from rice, with demand for it increasing in Asia, Latin America and especially in Africa.

Yet rice isn’t easy to cultivate. Most rice is grown in paddies filled with around 10 cm of water. If levels rise too high, the fragile plants can easily be inundated and die. Low-lying river deltas in Asia, where 90% of the world’s rice is produced, are prone to seasonal flooding.

Rice crops can also be destroyed by saltwater intrusion, given that deltas are on the coast. Irrigating rice with water that is too salty risks killing 100% of the crop. According to Science News,

In a 2015 and 2016 drought [in Vietnam], saltwater reached up to 90 kilometers inland, destroying 405,000 hectares of rice paddies. In 2019 and 2020, drought and saltwater intrusion returned, damaging 58,000 hectares of rice. With regional temperatures on the rise, these conditions in Southeast Asia are expected to intensify and become more widespread, according to a 2020 report by the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

Rice-growing areas can also be negatively impacted by extreme heat. The plants are most vulnerable in the middle phase of their growth. Temps above 35 degrees C can diminish grain counts in weeks or days. Last April in Bangladesh, just two days of +36 destroyed thousands of hectares of rice.

Conclusion

The fact that the world relies on only three food staples for 51% of its calories, all of which have skyrocketed in price, to me is very alarming.

Climate change was already having an impact on food production before the covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine brought the global food crisis to the attention of mass media.

The effects of droughts and floods, covid, and disrupted food shipments out of the Baltic Sea region, are all being passed up the food supply chain to the consumer.

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia, a major producer of natural gas, needed to make fertilizer, and the world’s largest exporter of wheat, is adding to higher grocery bills, including in North America.

Covid exposed the weaknesses in our supply chains. The war has revealed how some of the countries most vulnerable to food price hikes, and social unrest, are dependent on the Russian-Ukrainian bread basket.

We know what happens when people go hungry: they take to the streets.

When the price of bread in Egypt spiked in the early 2010s, and the government didn’t make any more subsidized bread available, the ensuing protests led to the Arab Spring.

I see the war in Ukraine, covid, supply chain interruptions, inflation and climate change coalescing into a perfect storm of unaffordability that could eventually erupt into mass social unrest, based on the lack of, or too expensive food.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.