Green energy investment matches fossil fuels for the first time – Richard Mills

2023.01.28

The shift to a world powered by renewable energy and run on electric vehicles may have its critics, but there’s no arguing with the numbers.

Last year the amount of money invested in decarbonizing the world’s energy system surpassed a trillion dollars for the first time. 2022 was also the first year that the $1.1 trillion which poured into the energy transition matched the $1.1T global investment in fossil fuels.

Another record: the year-on-year increase of >$250 billion (2022 vs 2021) was the largest ever jump, according to a recent Bloomberg story. While there has been $6.7 trillion invested in the energy transition since 2004, the article points out that it took eight years to reach the first trillion, less than four years to reach the next trillion, and under one more year to reach the latest trillion. In other words, the investment in green energy is accelerating dramatically.

Unsurprisingly, renewable power and electric vehicles received the lion’s share of the investment dollars, with more than 350 gigawatts of assets built and sales of >10 million EVs globally. Electrified transport is growing faster than renewable energy. Of the close to $500 billion in transport dollars invested, $380 billion went to passenger EVs. Other sectors received relatively less, with public charging infrastructure seeing $24 billion, $23B spent on two- and three-wheelers, $15B flowing to electric buses, and commercial vehicles getting $8 billion.

One last point from the article: while a trillion is obviously megabucks, it’s not enough to meet net-zero requirements by 2050. To get there, the world would need to immediately triple this $1.1 trillion spend — and add hundreds of billions of dollars more for the global power grid.

Cost pressures

Yet there is a disconnect between the huge amounts of money being channeled into green energy and transportation, and the metals needed to build the renewable power facilities, and all the electric vehicle infrastructure, including the cars themselves, their minerals-intensive batteries, and charging ports. Take for example, copper.

Millions of feet of copper wiring will be required for strengthening the world’s power grids, and hundreds of thousands of tonnes more, are needed to build wind and solar farms. Electric vehicles use over twice as much copper as gasoline-powered cars, which contain about 30 kg. There is more than 180 kg of copper in the average home.

To build more mines obviously requires investment (Goldman Sachs says mining companies will need to spend about $150 billion in the next decade, to address an 8-million-ton copper deficit), but mining firms are also being challenged with costs, along with a creeping resource nationalism, in some of the biggest metal-producing countries.

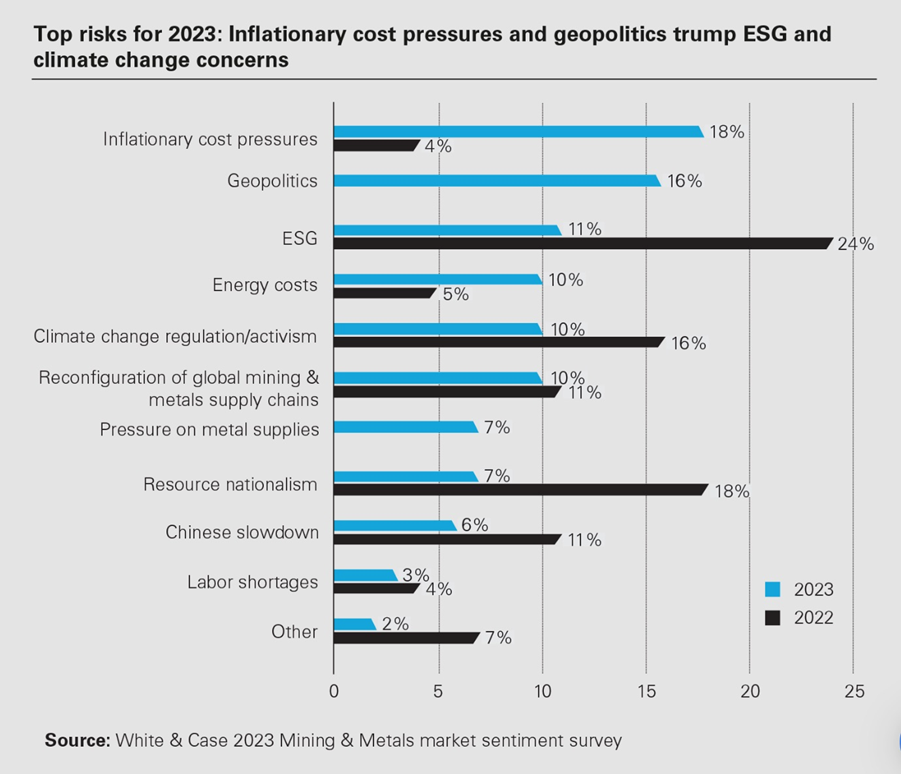

A recent White & Case survey found that 18% of mining industry survey participants cited inflationary cost pressures as the largest risk in 2023. This is up from just 4% in 2022. High energy costs break out as the fourth largest concern, at 10%. (unsurprisingly considering that diesel fuel is a major mining cost input — Rick)

The survey results, via The Northern Miner, reflect a marked change from 2022, when ESG dominated the perceived risks — 24% compared to 11% in 2023.

Resource nationalism is becoming a bigger concern, as governments in developing countries where mining often takes place, particularly Latin America (read more below) try to extract more revenue from mine operators. The survey flagged increased taxation as the most likely manifestation of resource nationalism in 2023, with over two-thirds of respondents (68%) expecting resource nationalism to increase this year.

Metals boom imminent

While copper, zinc and aluminum were all down more than 10% in 2022, prices are recovering, driven chiefly by two factors: the rebound in demand from China, as it its economy re-opens following strict covid-related closures and restrictions; and the continued decline in the US dollar (DXY), which has fallen from around 114 at the end of September 2022, to the current 101.96 (commodity prices and the dollar generally move in opposite directions). That’s nearly a 12% drop.

Check out the chart below. Over the past six months, copper has gained 27%, zinc is up 14%, aluminum is higher by 6%, and gold is at an astonishing $1,927 an ounce, only about $75 away from its record-high reached in 2020.

Bullish outlook for metals in 2023

While a global recession in 2023 will obviously slow the demand for metals and other raw materials, there are those who say that commodity prices are expected to remain high, in everything from oil to copper to wheat.

The Washington Post published an op-ed by Javier Blas, former Bloomberg News reporter and Financial Times commodities editor, stating that The global economy is hard-pressed to satisfy its own commodity needs. Despite the past year of sky-high prices, the natural resources industry isn’t rushing to invest in more capacity to alleviate supply shortages. Without an investment boom, the only way to rebalance the market in the new year is through lowering demand.

We’ve heard this argument numerous times over the past year. To “kill demand” central banks hike interest rates, thereby incentivizing consumers to save, and discouraging homeowners and businesses from borrowing. But this tactic does nothing to alleviate supply interruptions caused, for example, by the war in Ukraine. Nor does it address the above-mentioned mine supply constraints. Blas rightly points out that, unless mining companies build more mines, which would increase supply, the only way to bring down commodity prices is by influencing them on the demand side, through interest rate increases. Yet, the impact will be limited, because even if macroeconomic forces ease some commodity cost pressures, microeconomic factors, such as low inventories and limited spare capacity, will keep prices higher than during past recessions in 2023.

Take a moment to digest what is being said here. Even if tight monetary policy works in suppressing inflation to some degree, in fact, even if they drive the world economy into a recession (almost half of Americans think we’re already in a downturn due to still-high inflation) that won’t be enough to cancel out prices being ratcheted higher due to tight supply conditions.

Limited supply is prevalent in two of the most important metals sub-sectors, zinc and copper.

Zinc

According to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG), global refined lead and zinc markets are likely to be in a deficit in 2023.

Zinc should be in a 297,000 tonnes deficit in 2022 and 150,000 tonnes deficit in 2023, states ILZSG.

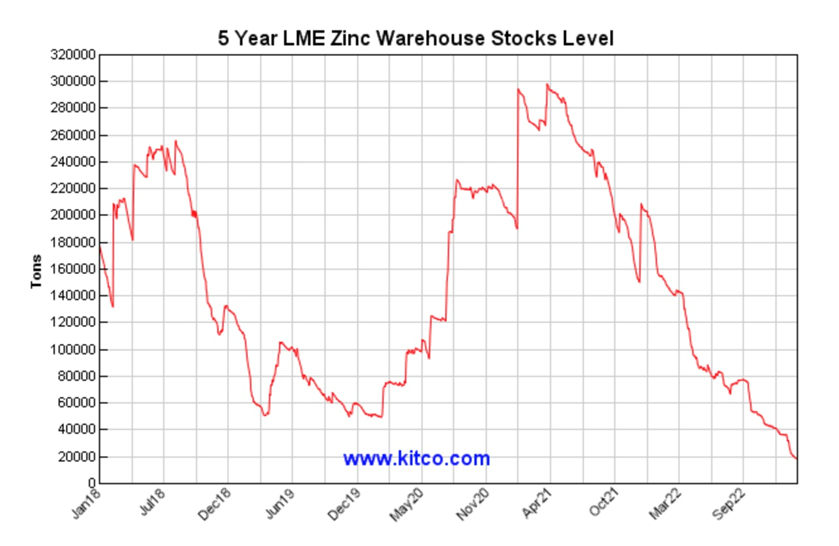

Zinc’s current price of USD$3,490 a tonne is a long way from last March’s record-high $4,896, but physical buyers are still paying record premiums for the metal, due to dwindling warehouse stocks, which have slid to a five-year low of 20,000 tons. From a one-year low of around $2,755, in mid-October, spot zinc has clawed back 26%.

Some very large zinc mines have been depleted and shut down in recent years, with not enough new mine supply to take their place.

MMG’s shuttered Century Mine in Australia, for example, used to supply 4% of the world’s zinc. Between the shutdown of the Lisheen Mine in Ireland, Century, and Glencore’s Brunswick and Perseverance mines in Canada, over a million tonnes was ripped from global zinc production.

Most recently, zinc supply in Peru is under pressure. Earlier this month it was reported that Nexa Resources halted production at its Atacocha San Gerardo open-pit zinc mine due to a local community blockading a road.

While Nexa says the obstruction will not have a material impact on Atacocha’s production, it’s not the first time this has happened.

The company faced two road blockades at the same site last year. The first one in March, which cost the miner 300 tonnes of zinc production, and another one in August (Mining.com).

The closed zinc mines represent an estimated 10 to 15% of the zinc market. On the flip side, there have been few discoveries or big zinc projects planned. This has set the zinc market up for a supply shortage. Remember, zinc is the fourth most common metal in the world, meaning no let-up in demand. This, combined with zinc deficits, can only mean one thing: higher prices.

Copper

A global shortage of copper could reach 8 million tonnes by 2032, as soaring demand fails to be matched by new copper mines. The rate of supply increases required, is equivalent to building eight copper mines the size of Escondida, the largest in the world, per year, for the next eight years. This is wildly optimistic.

Like zinc, a big part of the copper supply story is dwindling inventories. That, combined with red-hot demand for copper futures, is keeping prices elevated.

Copper inventory right now is less than four days, meaning that combined refined copper stocks in LME, SHFE and bonded Chinese warehouses are only four days worth of global consumption. The indicator is normally measured in weeks.

LME copper warehouse inventories plummeted from 180,000 tons last May, to the current 80,000t. COMEX copper stocks have fallen from 37,000 tons on the 30th of November, to 32,500t.

On Jan. 18, futures exchange operator CME Group said open interest on its copper options reached a record-high 137,574 contracts. Open interest is a measure of investors’ participation in a market. It tallies the number of options contracts that are yet to be settled.

CME’s monthly copper options posted a 41% increase in trading activity, with open interest of 82,599 contracts at the end of last year, hitting a record high. The Shanghai Futures Exchange’s copper contract, launched in 2020, registered year on year growth of 36%, Reuters said.

The physical market for copper, meanwhile, has tightened considerably, with much higher premiums being paid for immediate delivery.

Beyond tight physical markets, dwindling inventories, hot futures trading, and robust demand for copper as China re-opens its economy, resource nationalism in the world’s two largest copper-producing countries — Peru and Chile — is threatening mine production, and stalling investments in future projects.

Peru has been rocked by a series of mining conflicts over the past two years, as communities empowered by leftist ex-President Pedro Castillo, press their demands. Castillo was impeached in December and replaced by Vice President Dina Boluarte.

A fresh wave of protests hit Peru’s major operations in early 2022, including Glencore’s Antapaccay Mine, Southern Copper’s Cuajone and MMG’s Las Bambas, the country’s fourth-largest copper mine and the world’s ninth biggest.

As of Jan. 19, Las Bambas hadn’t shipped any copper concentrate since Jan. 3, due to security concerns. The mine is currently operating around 20% of capacity. Glencore’s Antapaccay is also facing restrictions, Bloomberg said, adding the two mines together account for nearly 2% of the world’s copper output. They also share highway access to ports.

Earlier this month, the Swiss firm said a group of citizens arrived at the site, demanded that the operation be stopped, and that Glencore issue a communique asking for the resignation of President Boluarte. The people then forced their way into mine facilities, stole workers’ belongings and set fire to the housing area. A week earlier, activists broke into the water plant and started a fire. A source said the plant provides drinking water for over 6,000 people in nearby communities.

Antapaccay had only been operating with 38% of its workforce due to protests. Following last Friday’s attack, Glencore decided to halt operations.

On Friday, Jan. 27, Bloomberg reported about 30% of Peru’s copper production is at risk due to violent protests.

The disruptions coincide with operational setbacks and regulatory headwinds in neighboring Chile, and the prospect of a mine shutdown in Panama as the government there seeks a bigger share of profits.

First Quantum Minerals was forced to halt operations at its Cobre Panama Mine after failing to agree to royalties under a new contract. In the latest on the dispute, the Panamanian government says it opposes First Quantum’s request to expand its copper mining operations.

In Chile, a left-ward shift is a mark against the top copper producer as far as attracting mining investment. Although Chile’s constitutional assembly has rejected plans to nationalize parts of the mining sector, the government is now weighing how much to increase royalties; a decision is expected soon.

Codelco’s production declined in the first nine months of 2022 and is expected to fall further this year on worsening ore grades.

Reuters reported this week that Chile’s copper production will grow at a slower rate than previously hoped. According to Cochilco, the state copper regulator, red-metal output will peak at 7.14 million tonnes in 2030, two years earlier than anticipated as delays hit mining projects. This is well below the 7.62 million-tonne 2028 peak the regulator had estimated in its decade outlook a year ago.

The report forecasts production in 2023 will be 5.467 million tonnes in 2023, and 5.891Mt in 2024. However, Reuters states, its projections depend on all planned mining projects in the current portfolio coming online, adding that projects to maintain and expand current mines would not be enough on their own to meet projections.

In other words, any delays or cancelations, of new mines, and Chile will fail to meet its own copper supply projections.

Problems with copper production, aren’t only happening in Latin America, as governments there are pressured by groups intent on addressing rampant inequality, and want to tap miners for more cash.

The DRC government in Africa is criticizing China for failing to meet its end of a resource for infrastructure bargain struck in 2008. The agreement mandated Chinese companies invest $3.2 billion in the Tenke Fungurume copper-cobalt mine (China Moly has an 80% stake) and another $3 billion in infrastructure funded by the mine’s revenue.

But according to current President Felix Tshisekedi, while China receives most of its minerals, the Congo hasn’t even released a third of the infrastructure funds, meant for roads and buildings.

“We’re happy to be friends with the Chinese, but the contract was badly drawn up, very badly,” Tshisekedi said, via Bloomberg. “Today, the Democratic Republic of Congo has derived no benefit from it. There’s nothing tangible, no positive impact, I’d say, for our population.”

The road to no

In the United States and Canada, resource nationalism of a different type is becoming more prevalent. Here, governments are under pressure from environmental, indigenous and anti-development groups to say no to mining.

Unlike poorer nations whose populations need the metals revenue to pay for important social services and to earn hard currency to buy imports, in the rich, developed West, citizens have the luxury of protest. They are comfortable.

Mining is seen by some as a necessary evil whose environmentally destructive practices should be stopped, or at least, shouldn’t take place anywhere near them. They don’t realize or care that without mining, there would be no modern society: no steel to make bridges, no copper wiring that powers homes and businesses, no uranium to fuel nuclear reactors, no jewelry, no rare earths to make smart phones, solar panels, color monitors and TVs. Usually they want resource extraction halted, at all costs – the minerals or the oil kept in the ground.

In a previous article we detailed the Biden’s administration’s anti-mining record, to the end of 2021.

Anti-mining decisions could slam the brakes on US electrification plans

The latest example concerns Antofagasta’s Twin Metals copper and nickel mining project in Minnesota. On Thursday, Jan. 26, the U.S. Department of the Interior blocked mining in northeastern Minnesota for 20 years, driving a dagger into the heart of the project.

The proposed underground copper-nickel mine, had progressed to the point of a 2019 feasibility study. A coalition of groups opposing the mine then went to court to challenge a Trump-era decision that opened the door to the mine, located near a wilderness area.

In August of last year, an Antofagasta subsidiary sued the US government in a bid to revive the project, which Biden administration officials had blocked due to concerns it could pollute a waterway.

There is no doubt that the mine, if built, would have been a major domestic source of copper and nickel. According to Twin Metals, the minerals within the Maturi deposit, part of the Duluth Complex geologic formation, is one of the largest undeveloped deposits of its kind in the world, with more than 4.4 billion tons of ore containing copper, nickel and other strategic minerals.

The fact that these minerals are condemned to stay in the ground for the next 20 years, while the Biden administration makes all sorts of promises to meet green energy targets, is a failure of policy at the highest levels.

Of course, here in Canada we aren’t immune to “woke” politicians who have the ear of pressure groups and who clearly do not understand the connection between mining and clean energy/ decarbonization/ electrification.

It takes seven to 10 years, at minimum, to move a mine from discovery to production. In regulation-happy jurisdictions like Canada and the US, the time frame is up to 20 years.

What does this mean for metals supply? It means that recent discoveries won’t have any measurable effect on the supply for up to 20 years from now.

A report a few years ago from the Fraser Institute (the date is irrelevant, believe me nothing has changed), states that one of the themes to emerge from a survey’s comment section, is a perception that permit times have grown longer, and more onerous over time (by permit times, we are talking about how long it takes to get approvals for mineral exploration).

This is a problem that flies in the face of another perception, that Canada is a great place to go mining.

Canada has a prolific mining history. In fact it could be argued that mining is to our economy what hockey is to our culture. Canadians are known for their ability to find, fund and build mines. Some of the biggest mining names are Canadian: Ross Beaty, Pierre Lassonde, Ian Telfer, Robert Friedland.

We had the Klondike Gold Rush that opened up the north – first to grizzled prospectors that toughed it out through brutally cold Yukon winters, then to the first mining companies that displaced the hard-scrabble gold panners with mechanized equipment.

The country is famous for its vast reserves of gold, copper, coal, iron ore and uranium. We are the fourth largest gold producer, and many of the world’s junior resource companies are listed on the TSX or the TSX Venture Exchange; most juniors are based in Vancouver.

While some provinces, for example Saskatchewan and Quebec, regularly rate highly in the Fraser Institute’s annual investment attractiveness index, my home province of British Columbia is just as often the laggard of the bunch.

BC mining? Hurry up and wait

Recently I came across an article by Business in Vancouver, that talks about the byzantine process of mine-building in BC — the upshot of which, is it now takes an average of 13 years to advance a mine in this province from discovery to construction, not production. Note that it takes a further 2, 3, sometimes 5 years to build the mine, and the process, at any stage, can be shut down at any time by either of 2 levels of government or the indigenous group on whose territory the project is located.

An excerpt is worth quoting in full:

So, you want to spend hundreds of millions of dollars – possibly billions — building a new copper mine in British Columbia.

First, you may have to spend a few million dollars explaining your plan to relevant First Nations and local communities before you even submit an application for an environmental permit.

That way you’ll know up front whether the province will even accept your application to the Environmental Assessment Agency. Your project may be dead before it is even subjected to an environmental review.

Be sure to read UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People) and DRIPA (Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act).

Once you’ve done that, and submitted your application, you will, at some point, probably need to deal with the ministries of ECCS, EMLCI, IRR, and FLNRORD.

That’s just the provincial level. Federally you will probably have to deal with Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Impact Assessment Agency.

This should not take long – about 13 years. (That is the average in B.C. for taking a mining project from discovery to approval and construction in B.C., though things can go quicker if you have local First Nations on board.)

Bill C-69 has only made the mine-building process slower, and more bureaucratic.

Road to a mining ‘yes’ littered with obstacles in Canada

As we wrote previously, the 2019 legislation broadens the scope of the assessment process and adds more consultation with the public and particularly indigenous groups.

There is nothing wrong with consultation, in fact it is a necessary part of making changes to the land base given our fractious relationship with First Nations, but this legislation introduced a whole new level of uncertainty to the environmental review process that is critical to the passage of a mining project.

As an industry, mining is so capital-intensive, investors need a great deal of certainty that their money will be safe and offer good returns for years, often decades, from exploration to production to mine closure. Uncertainty keeps capital away, delays add costs to already hugely expensive construction plans.

Tough but fair resource regulation is necessary and expected. Unfortunately, Bill C-69 does nothing to assuage the industry’s concerns that the environmental assessment process is hampering investment in the sector.

So how is mining progressing in British Columbia? Unfortunately, the industry has become something of a political football, with governments of both stripes keen to throw the pigskin especially during elections. Many will remember then-Premier Christy Clark’s visit to a northern BC mine, donning a hard hat for TV cameras, a successful approach by the way, that helped win the Liberals the election.

Clark and her BC Liberals were somewhat disingenuous in their claims that BC under them was more mining-friendly. It’s true that new mines like Red Chris started up under the Liberal banner, but the approvals were granted under previous NDP governments.

Current BC Premier David Eby is at it again, I noticed. Talking Monday to the AME Roundup conference in Vancouver, Eby bragged there are currently eight new mines or mine expansions in the works, worth CAD$6.6 billion.

A quick look at some of these mines shows they’ve been under development for years, if not decades.

The Premier underground mine and the Eskay Creek open-pit mine are both ‘brownfield’ projects with numerous historical permits already in place.

The Blackwater Gold open-pit gold-silver mine has been in the permitting stage for almost 10 years. Richfield Ventures started diamond drilling in 2009.

And the biggest of them all, Seabridge Gold’s KSM project, has been “in development” for as long as I can remember.

And who doesn’t remember Barkerville Gold Mines Ltd? Osisko is planning 2024 production.

Despite all the road blocks on the path to building a mine in British Columbia things can get done. But it’s too bad Eby, like Clark, has to talk someone else’s book.

Conclusion

Anti-mining decisions in Canada and the United States of course tie into the copper shortage narrative. Banks and analyst firms are telling us we need to find the equivalent of one Escondida copper mine per year for the next eight years, to erase an expected 8Mt deficit by 2032.

We started off this article noting how green energy investments in 2022 for the first time ever matched fossil fuel investments, each $1.1 trillion. The capital, the interest and the will of governments is there, but where are the metals?

The Biden and the Trudeau administrations talk a good game, about net-zero emissions and all that, but when the chips are down, they fold to special interests instead of seeing the big picture: without mining there is no energy transition.

The demand for green-energy metals especially copper and EV battery ingredients such as nickel, graphite, lithium and cobalt, is heading much higher, but the supply of metals is encountering obstacle after obstacle — from resource nationalism and mine closures, to mal-investment/ no investment to lower grades and soaring cost inflation.

When the powerful force of metals demand hits the immovable object of dwindling supply – the explosion in prices is going to be epic.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.