Drought conditions improving across Western Canada, US – Richard Mills

2023.03.20

Last year in Western Canada and the US was unusual due to the warm weather that lingered well into October, extending the forest fire season as well as late-summer drought conditions.

A story in Newsweek said in the week of Oct. 12-18, nearly 50% of the United States and 59.4% of the lower 48 states were in drought, affecting nearly 135 million people.

Last fall, we reported that some parts of the US may face continued dry conditions throughout this winter amid the La Nina weather pattern. La Nina typically takes place once every three to five years, but in 2022 La Nina occurred for the third consecutive year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

An NOAA report on Oct. 20 said “parts of the Western U.S. and southern Great Plains will continue to be the hardest hit [by drought] this winter.”

This includes California, which has suffered through its driest three-year period on record.

Along with low lake levels on Mead and Powell, dry conditions caused record water-level lows in places along the Mississippi River in October, according to National Weather Service data. In Memphis, Tennessee, the river fell 10.75 feet, the lowest ever recorded in the city.

Deadpool on Lake Powell could arrive as soon as July

In Western Canada, a late-summer drought prompted a state of emergency in one southern British Columbia region, caused poor crop yields in the northeastern part of the province, and had BC’s energy regulator rationing the water supply for some oil and gas companies.

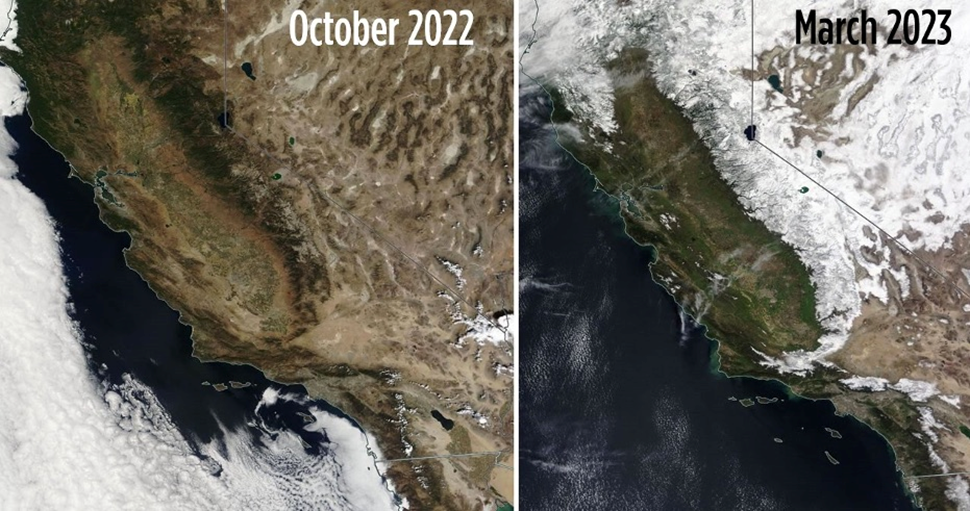

Six months later, the situation has changed dramatically.

US

During the last half of February, more Pacific weather systems held together over the West, with some moving slowly and dumping copious amounts of precipitation across California to the Rocky Mountains. The Pacific moisture fell in the form of flooding rains and heavy snow, especially over central parts of California.

According to U.S. Drought Monitor,

The above-normal precipitation and snowpack resulted in contraction or reduction of the intensity of drought over large parts of the West, especially in central California. Above-normal precipitation also contracted or reduced drought intensity in parts of the Plains and coastal Southeast, across the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys, and in the Great Lakes and Hawaii. Heavy rain from repeated passages of frontal systems caused multiple categories of improvement over eastern Oklahoma. But areas experiencing a drier-than-normal month saw drought expansion or intensification. These areas included parts of the Pacific Northwest, southern Plains, Florida, and central Gulf of Mexico coast.

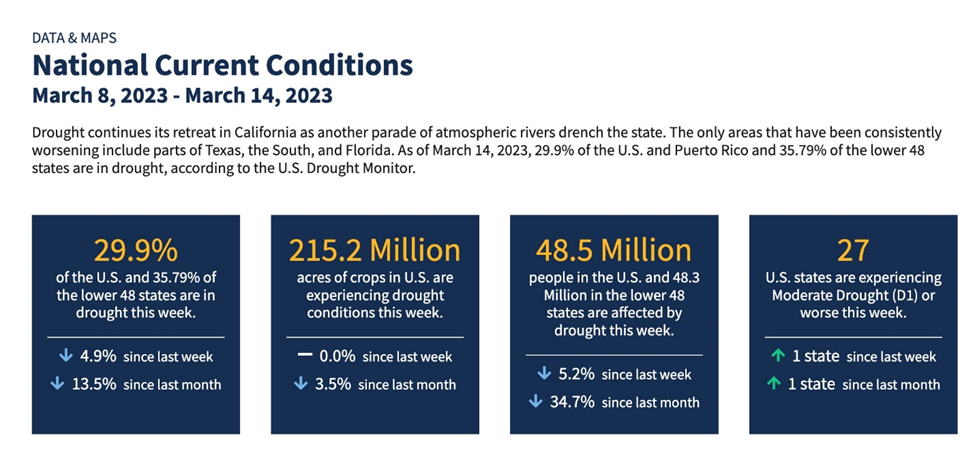

For the week ending March 14, Drought.gov said Drought continues its retreat in California as another parade of atmospheric rivers drench the state. The only areas that have been consistently worsening include parts of Texas, the South, and Florida. As of March 14, 2023, 29.9% of the U.S. and Puerto Rico and 35.79% of the lower 48 states are in drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Remember, in mid-October, nearly 50% of the United States and 59.4% of the lower 48 states were in drought.

USDM cautions that “The heavy precipitation at the end of the month over the West was not enough to overcome the excessive dryness that occurred earlier in the month, with monthly precipitation ending up drier than normal large parts of the West, especially in the Pacific Northwest. The weather systems missed large parts of the Great Plains, Gulf Coast, and Northeast, which were also drier than normal for the month.”

Still, “according to USDM statistics, the week of February 28 ended the streak of 40% or more of the [contiguous US] that had been in moderate drought or worse. This streak lasted for 126 weeks, which is a record in the 22-year USDM history and double the previous record of 68 consecutive weeks (June 19, 2012 to October 1, 2013).”

California is the poster-child for a wetter than normal winter busting a punishing four-year-long drought; the state saw its three driest years ever, from 2020 to 2022.

But a series of blizzards and “atmospheric rivers” have helped restore the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada and refilled depleted reservoirs.

According to ABC News, downtown Los Angeles has seen nearly two feet of rain this winter, making it the 14th wettest in 140 years of record-keeping. This week’s atmospheric river brought at least two inches to downtown and more rain is in the forecast for next week.

The same news organization said 99% of the Bay Area and 64% of California is now drought-free.

ABC News cited three factors that led to California’s abnormal rainfall in what was supposed to be a La Nina year: the jetstream setting up further south than it normally would in a La Nina year; the Madden-Julian oscillation phenomenon being in a favorable position for California to see enhanced rainfall; and a warming climate holding more moisture in the atmosphere, meaning more rainfall.

And more snow.

The latest survey taken by the state’s Department of Water Resources, in the Central Sierra Nevada mountains, measured 116.5 inches (almost 10 feet) with a snow-water equivalent of 41.5 inches. That is 177% of average for March 3, according to the DWR.

Statewide, the snowpack is currently at 190% of average, which is second only to the record set in 1982-83.

After receiving 33 inches of rain since Oct.1, officials in Santa Rosa canceled the city’s drought emergency plan, which asked the community to reduce water usage by 20%. It now has four years of water supply in place.

“I’ve seen an incredible pendulum swing from the lowest low to rising 70 feet in a short period of time,” said Chris Schooley from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, referring to the Lake Sonoma reservoir.

Restrictions are reportedly being lifted for 7 million Southern Californians. Since June 2022, the rules required residents to either limit outdoor watering to one day a week, or live within certain limits on volume.

However, the move by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California came with a warning:

“Southern California remains in a water supply deficit,” said Tracy Quinn, chair of the MWD’s One Water Committee. “The more efficiently we all use water today, the more we can keep in storage for a future dry year.”

Indeed the nine massive storms to hit the Bay Area down to San Diego and in the Central and Southern Sierra Nevada, after Christmas, followed by a series of unusually cold storms coming out of the Gulf of Alaska, must be put in perspective.

For example, it will take more than a few weeks of heavy rain and snow to replenish the once-mighty Colorado River.

Last April Lake Mead, America’s largest manmade reservoir, and a source of water for millions, fell to an unprecedented low. Mead has been shrinking amid a 23-year mega-drought (it’s actually the worst drought in 1,200 years) in the Southwestern United States.

The graph below shows how low Lake Mead’s water level has dropped compared to 2020 and 2021.

Hunger stones, wrecks and bones

An even more frightening scenario is developing at Lake Powell, a reservoir along the Colorado River that is a quarter of its former size.

According to a story in The Washington Post, if the lake drops another 38 feet, the surface would be approaching the tops of eight underwater openings that allow river water to pass through the [Glen Canyon] hydroelectric dam…

If that happens, the massive turbines that generate electricity for 4.5 million people would have to shut down — after nearly 60 years of use — or risk destruction from air bubbles.

The federal government is predicting the minimum water level for generating power could occur as soon as July, 2023. An even worse possibility, the dreaded “deadpool”, would happen if the lake level falls so low, that only small amount of water pass through the dam.

According to The Post,

Reservoirs and groundwater supplies across the region have fallen dramatically, and states and cities have faced restrictions on water use amid dwindling supplies. The Colorado River, which serves roughly 1 in 10 Americans, is the region’s most important waterway…

[Last] year, the Biden administration called on the seven states of the Colorado River basin to cut water consumption by 2 to 4 million acre-feet — up to a third of the river’s annual average flow — to protect power generation and avoid such dire outcomes. But negotiations have not produced an agreement…

With Lake Powell at one-quarter full, [the Bureau of] Reclamation has begun a feasibility study on the prospect of harnessing the deeper bypass tubes for power generation…

Being forced to switch to the four smaller bypass tubes would instantly cut the dam’s capacity to release water by two-thirds. If water levels and pressure fell further, these pipes would quickly lose the ability to deliver the millions of acre-feet of water the lower basin states consume each year, the Glen Canyon Institute wrote in a report in August on low water scenarios.

Receding water levels are already impeding the ability of the Glen Canyon Dam to produce power; the dam currently generates about 40% less power than what has been committed to customers. What power the dam fails to generate, its customers have to buy on the open market. The cost differential is huge. The standard rate at Glen Canyon is $30 per megawatt hour, but customers have faced prices as high as $1,000/Mwh.

The dam is also important because it’s what is known as a “black start” facility for the country’s largest nuclear plant, the Palo Verde Generating Station in Arizona. If the plant shuts down and needs to restart, the dam could provide power to bring it back online.

In a recent CBC story titled ‘An American Water Crisis’, it was reported that, to avert catastrophe, the US government will, within weeks, propose historic cuts in water access, to protect drinking water for millions of people, electricity and food.

A few highlights from the article, edited for brevity and clarity:

- This indispensable waterway supplies farms that feed hundreds of millions of people, throughout the continent — including Canadians.

- But there’s a problem. A classic imbalance of supply and demand: Too little water supply, too much demand. The river, in other words, is running a deficit. It’s been happening since around 2000 and it’s getting worse. There’s a trifecta of factors causing the trouble: A long-ago math miscalculation; then a population boom; and finally a hotter, drier climate.

- This river system that was built to irrigate farms wound up supplying some 40 million people. It’s being over-used by about one-third.

- The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation wants a reduction by millions of acre-feet which, combined with existing reductions, amounts to a clawback of 20 to 40% in water use.

- Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting over (Mark Twain). Any federal plan will provoke lawsuits, with potentially lengthy legal fights. The biggest losers in two recent rounds of cuts were central Arizona farmers. Arizona has already lost 21% of its river access entering this year. And that’s excluding the upcoming federal cuts. California, so far, has lost 0%.

Canada

Last fall, British Columbia issued a Level 4 drought warning, meaning adverse effects were likely to happen to three regions — Finlay Basin and Parsnip Basin in the north and on the Sunshine Coast.

The latter north of Vancouver made headlines due to its reservoir almost running dry.

But a dry, early fall on much of the Prairies has given way to a snowy and cold winter, with signs the persistent La Nina weather pattern is finally breaking up, The Western Producer reported in early January.

“Overall, we’re looking at a neutrality pattern. (There will) be pockets of good water here and there, pockets of drought here and there, but, overall neutral,” the agricultural publication quoted meteorologist Matt Makens.

“The most optimistic area of precipitation for me is out west, snow on the mountains, and I think the Rockies will pick up a fair amount of snowfall between now and spring,” added Makens.

The weather expert said we’re looking at a springtime transition away from La Nina and possibly the arrival of El Nino by early summer or fall.

Makens anticipates average precipitation on the Prairies this spring, but for areas along the central part of the Alberta-Saskatchewan border that have seen persistent dry conditions, “It’s going to take a lot of water, a lot of snowmelt in the snowpack to recover from that drought in those areas,” he said.

“Drought conditions across Canada continued to improve in most regions in February resulting in the removal of all Extreme Drought (D3). Snowpack improved slightly across much of Western Canada, which helped to reduce concerns for limited spring runoff, especially in British Columbia and parts of Alberta. Winter precipitation in the Prairie region to date was near- to above-normal across Alberta and through western and southern parts of Saskatchewan, while southeastern Saskatchewan and much of Manitoba received below-normal precipitation; these areas were one of few that saw an expansion of drought this month,” states a February 2023 Drought Assessment from Agriculture Canada.

And a summary:

“At the end of the month, 37% of the country was classified as Abnormally Dry (D0) or in Moderate to Severe Drought (D1 to D2), including 62% of the country’s agricultural landscape. There was no Extreme or Exceptional Drought (D3 or D4) reported this month.”

As for what the spring could look like in Western Canada, the CBC reported in mid-January that, while 2022 was a big improvement over 2021, when hot dry weather baked the Prairies, a good chunk of the region is still running a deficit of reserve soil moisture.

A farmer in Okotoks, AB, told a reporter, “If it turns hot and dry [for a few weeks] …it could be like 2021 all over again.”

Trevor Hadwen, an agroclimate specialist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, said precipitation has been pretty good this winter, which leaves the Prairies in a better position than at this time last year. Still, he agreed a lot still rides on what happens in the spring.

“If we receive above-normal spring moisture, we’re going to get off to a really good start,” said Hadwen.

“If we lose that snow early through a chinook and expose the soils to evaporating forces early in the season, which often happens, and we don’t get that spring moisture and the rains that we want, things will turn bad real quick.” (CBC News, Jan. 15, 2023)

Conclusion

A prolonged drought since 2000 in the Colorado River Basin (a study shows 2000-18 was the driest period in the US Southwest since the late 1500s) — which includes bits of seven western states and a part of Mexico — has made it impossible for the country’s biggest reservoirs, Lake Mead in Nevada and Lake Powell straddling the border of Utah and Arizona — to recharge fully.

This is a huge problem, considering that the Colorado River provides water for more than 40 million people including major US cities Las Vegas and Los Angeles.

Drought is also becoming prevalent in the Horn of Africa, China, Europe, Argentina, and even in British Columbia — known for its fast-flowing rivers and plentiful fresh water.

Drought affects not only the amount of water available for drinking and irrigation, but energy production (hydroelectric, nuclear, oil and gas/ fracking) and farming.

Higher temperatures, water scarcity, droughts, floods, and greater CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere, all have negative impacts on the yield of staple crops.

Since the 1990s, the number of weather-related disasters around the world has doubled, a pattern that greatly increased the risk of food insecurity and food prices. Sadly, this trend is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

Indeed we can’t be complacent. Though winter rains and snow have set up Western Canada and the US for a bountiful harvest, hopefully free of drought, every farmer knows it doesn’t take much — just a few weeks of hot dry weather early in the planting season — to ruin a crop.

As Project Syndicate wrote recently,

Water-related challenges – whether there is too much or too little, or whether it is dirty and unsafe – are already fueling chronic food and health insecurity in entire regions. Every 80 seconds, a child under five dies from a disease caused by polluted water; and hundreds of millions more are growing up stunted and with diminished lifetime prospects.

Making matters worse, we have entered a vicious cycle in which the interaction of the water crisis, global warming, and the loss of biodiversity and natural capital exacerbate all three. Wetland erosion and lost soil moisture risk turning some of the planet’s great carbon stores into new sources of greenhouse-gas emissions, with devastating consequences for the climate.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.