Data centers: Gluttons for power, water and minerals Part II – Richard Mills

2025.12.23

Grid stress

Stanford University notes that data center companies and utilities have to worry not only about how much power they consume, but how many new transmission lines will carry it.

Data centers: Gluttons for power, water and minerals Part I

For example, the Salt River Project in Arizona recommends a new substation and two new 230kV transmission lines. According to the company’s 2023 Integrated Systems Plan, “SRP will likely need to double or triple resource capacity at an unprecedented pace in the next decade” and that “hundreds of miles of new or upgraded transmission lines and nearly double the number of … transformers could be needed…”

In Santa Clara, California, the city council approved a 2.24-mile new overhead transmission line. Its utility, Silicon Valley Power, issued $143 million in bonds to pay for upgrading the grid infrastructure, while announcing a 5% increase to ratepayers.

And in rural Oregon, the Umatilla Electric Company is building a new 5.6-mile overhead 230kV power line to two towns, Boardmand and Hermiston, that are nodes of data-center growth.

Mish Talk ran a column asking how much additional power data centers need by 2035.

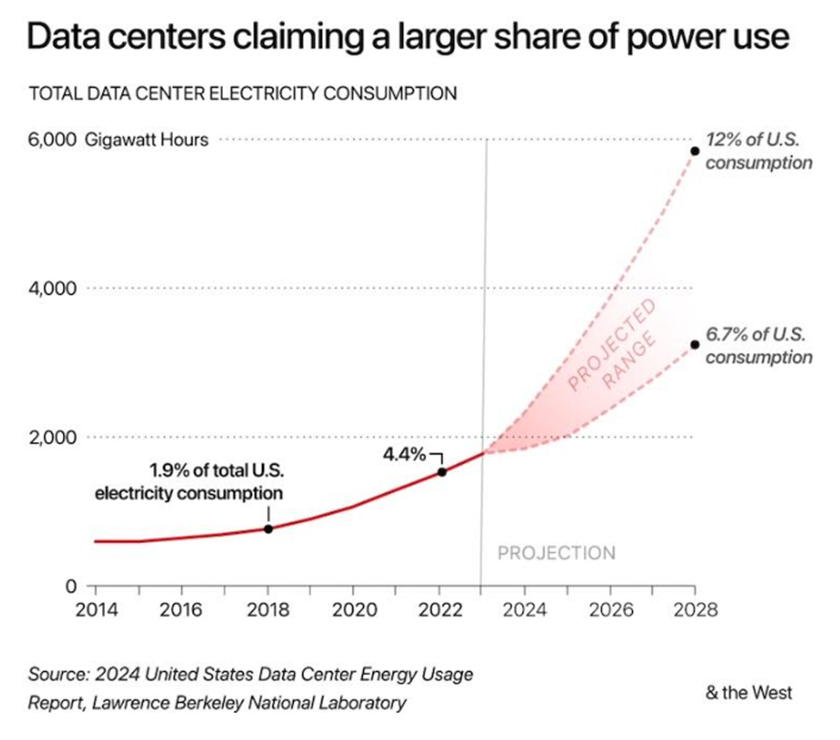

The US grid has not been able to keep pace with this demand. While utilities can likely generate sufficient power to meet data center needs, they face bottlenecks with transporting that power via transmission and distribution infrastructure. As a result, grid interconnection takes longer, there is more congestion on the network, and capacity is increasingly expensive. If the US continues to build high-voltage transmission infrastructure at its current rate, it will take at least 80 years to deliver what we need over the next decade. New data center projects will struggle to get timely access to power. In the US, 55 GW of data center IT capacity is expected to come online in the next five years. For comparison, this is 10 times the average power capacity used by New York City – and does not include the additional power needed for cooling systems…

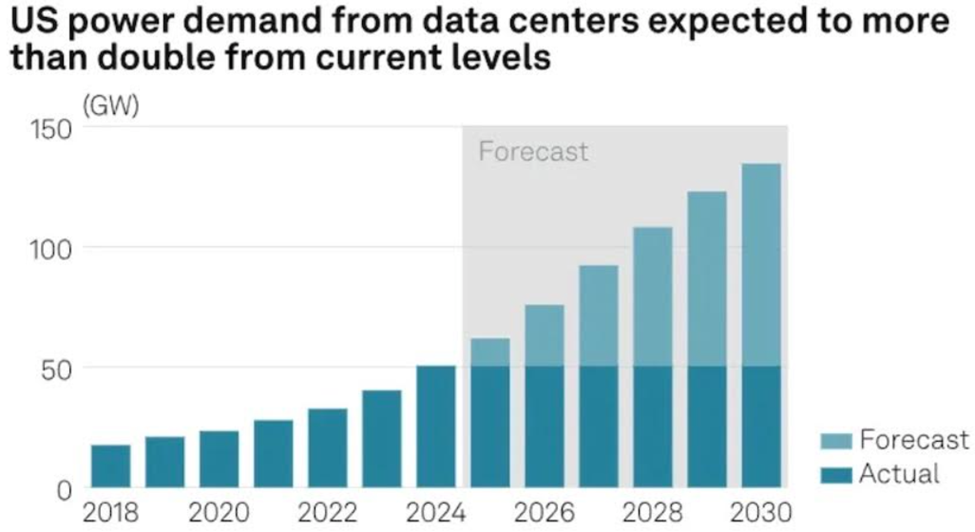

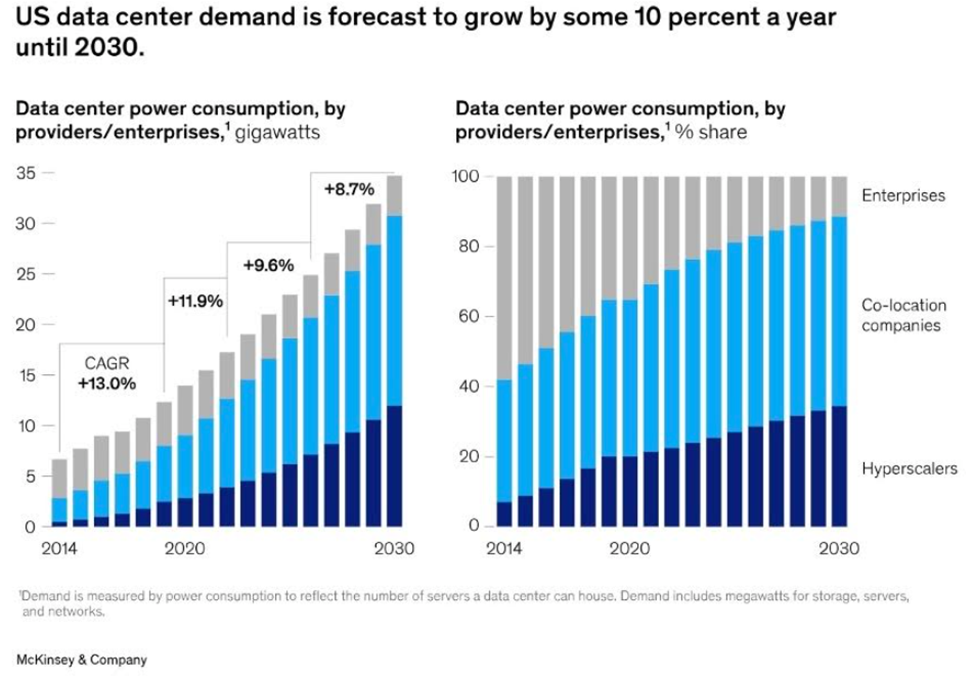

In October, S&P Global reported Data center grid-power demand nearly triple by 2030.

Data centers proliferating across the US will require 22% more grid power by the end of 2025 than they did one year earlier and will need nearly three times as much in 2030, according to the most recent forecast from 451 Research, part of S&P Global.

Energy security

Grid stress ties into energy security. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA),

Pressing threats and longer-term hazards are elevating energy to a core issue of economic and national security. Energy is at the heart of today’s geopolitical tensions, with traditional risks to fuel supply now accompanied by restrictions affecting supplies of critical minerals. The electricity sector – so essential to modern economies – is also increasingly vulnerable to cyber, operational and weather-related hazards.

The IEA notes a pivotal issue for electricity is the speed at which new grids, storage, and other sources of power system flexibility are put in place.

Investments in electricity generation have charged ahead by almost 70% since 2015 to reach USD 1 trillion per year, but annual grid spending has risen at less than half the pace to USD 400 billion. This increases congestion, delays the connection of new sources of electricity generation and demand, and pushes up electricity prices. Curtailment of wind and solar output is on the rise, as are incidences of negative pricing in wholesale markets, but slow permitting is holding back grid projects, as are tight markets for transformers and other components.

Carbon emissions

The dirty secret nobody wants to talk about? Data centers are mostly run on fossil fuel-powered electricity that emit large amounts of carbon.

The problem stems from the fact that data centers need power 24/7, 365 days a year. They can’t rely on intermittent power sources like wind and solar. A study by Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that the carbon intensity of electricity used by data centers was 48% higher than the US average.

Data centers tend to be clustered around dirtier grids like the coal-heavy mid-Atlantic region that includes Virginia, West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

While the tech giants are planning on building new nuclear plants, such plants cost billions and take several years to complete. Meanwhile, natural gas, a just-as-bad-as coal pollutant, accounts for more than half of the electricity generated in the US data-center hub of Virginia.

In 2024, fossil fuels including natural gas and coal made up just under 60% of electricity supply in the US. Nuclear accounted for about 20% and a mix of renewables comprised most of the remaining 20%, states Technology Review.

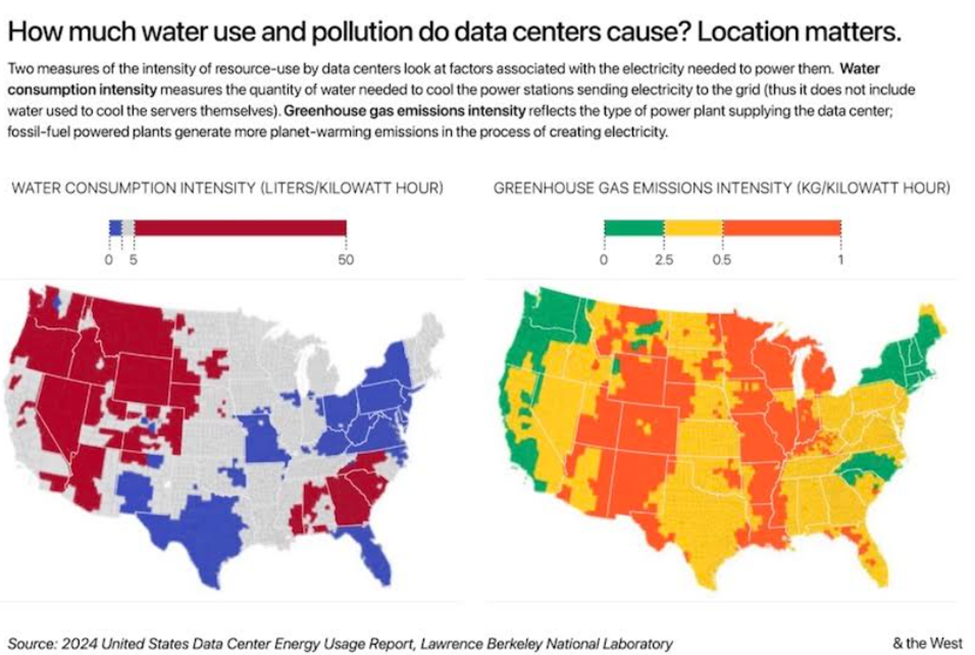

The carbon intensity of data centers — the number of grams of carbon dioxide emissions produced for each kilowatt-hour of electricity consumed — varies greatly according to each state.

In the charity runner case cited above, the AI-generated responses they requested amount to 2.9 kilowatt-hours of electricity. In California, generating that amount of electricity would produce about 650 grams of carbon dioxide pollution on average. But generating that electricity in West Virginia would nearly double it to more than 1,150 grams.

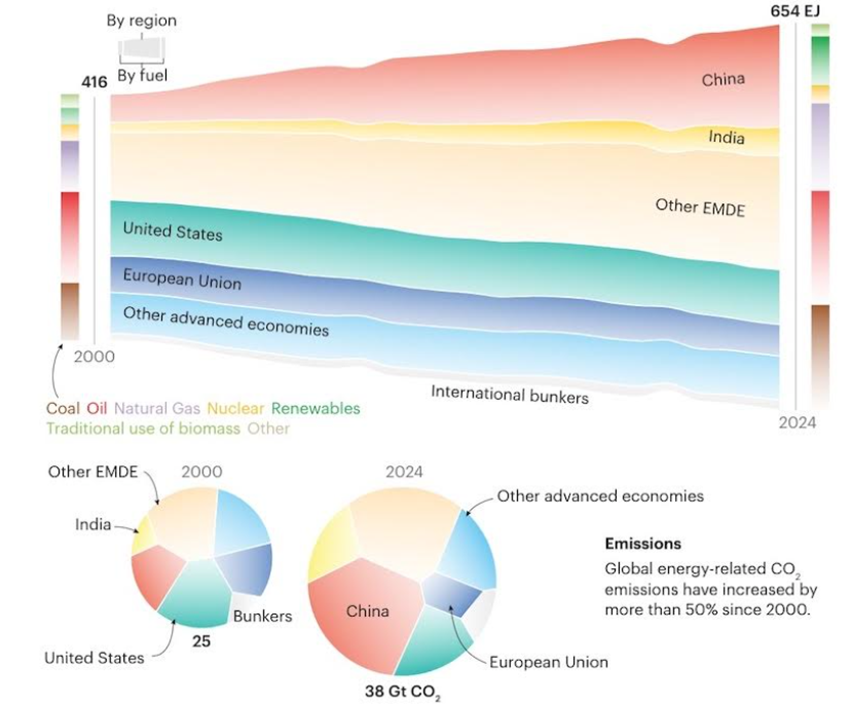

According to the IEA, global energy demand and emissions continue to grow.

In 2024, electricity use across a range of sectors expanded rapidly. While renewable power generation broke records, meeting more than 70% of the increase in electricity demand, global CO2 emissions also reached another all-time high.

The graphic below shows global energy-related CO2 emissions have increased by more than 50% since 2000.

Water consumption

Large data centers use substantial amounts of water, primarily for cooling systems. A single large facility can consume millions of liters of water per day, comparable to the daily usage of thousands of households. Global data center water consumption is projected to reach 1.2 trillion liters annually by 2030, raising concerns about local water scarcity, especially in drought-prone areas. (AI Overview)

According to the Environmental and Energy Studies Institute:

- Data center developers are increasingly tapping into freshwater resources to quench the thirst of data centers, which is putting nearby communities at risk.

- Large data centers can consume up to 5 million gallons per day, equivalent to the water use of a town populated by 10,000 to 50,000 people.

- Novel technologies like direct-to-chip cooling and immersion cooling can reduce water and energy usage by data centers.

Source: ECMWF Data Center, EESI

Why do data centers use so much water? It’s all about the need for cooling. As the centers use energy for typical operations and to meet AI requests, they need water to cool their processor chips so as to avoid damage through overheating.

EESI says a medium-sized data center can consume up to 110 million gallons (416.3 million liters) of water a year for cooling purposes. Larger data centers can guzzle up to 5 million gallons per day or 1.8 billion gallons a year.

Scientists at the University of California, Riverside figured out that each 100-word AI prompt is estimated to use one 519-ml bottle of water.

A data center’s water footprint is the sum of three categories: on-site water usage, water use by power plant facilities that supply power to data centers, and water consumption during the manufacture of processor chips.

Water usage can depend on several factors, including location, climate, water availability, size, and IT rack chip densities. The latter means that with the increasing number of data centers supporting AI requests, chip density is growing. This leads to higher room temperatures, necessitating the use of more water chillers — which remove heat from liquids. According to EESI, most data centers used a combination of chillers and cooling towers to avoid chip overheating.

Direct-to-chip liquid cooling and immersive liquid cooling are two standard server liquid cooling technologies that dissipate heat while significantly reducing water consumption. During immersive cooling, water or specialized synthetic liquids flood the chips, absorbing the heat.

Obviously hotter climates require more water for cooling.

But there’s a problem. One source recently wrote that nearly 7,000 of the world’s 8,808 data centers are built in the wrong climate — a new analysis finding that the vast majority are located outside optimal temperature range for cooling, 600 in locations considered too hot.

The analysis published by ‘Rest of World’ recommends that data centers operate most efficiently when inlet air temperatures fall between 18 and 27 degrees Celsius.

Above that band, cooling systems work harder, energy use rises, and costs increase. Below, condensation and reliability can become an inhibiting factor.

Based on that definition, nearly 7,000 data centers sit outside the recommended temperature range. Around 600 are sited in areas with average temperatures above 27C.

Around 80% of data center water is freshwater that evaporates. The remaining 20% is discharged into municipal wastewater treatment systems which can get overwhelmed.

In the energy section it was mentioned that that the carbon intensity of electricity used by data centers was 48% higher than the US average.

With 56% of the electricity used to power data centers in the United States coming from fossil fuels, a significant portion of data center water consumption is derived from steam-generating plants. Large boilers filled with water are heated with natural gas or coal to produce steam, which runs a turbine to generate electricity.

EESI noted that water withdrawals from these power plants are a significant source of water stress particularly in drought-prone areas.

Northern Virginia, where most US data centers are located, consumed close to 2 billions gallons of waters in 2023, a 63% increase from 2019.

Arizona has reportedly limited home construction in the Phoenix area to preserve groundwater.

Some of the big tech giants running data centers avoid disclosing their water usage. According to Stanford University’s ‘& the West’ magazine:

Google, which operates Oregon data centers at The Dalles, a city of 16,000 people not far from Morrow County, resisted disclosing its water use, paying $100,000 for the city’s lawsuit against The Oregonian, a Portland newspaper that had filed a public records request for the data. When the suit was dropped, Google’s water-use totals were public: 355.1 million gallons, a quarter of the city’s annual water use in 2021.

Oilprice.com recently wrote about the increasing water requirements of hyperscalers. Remember these are the largest data center run by tech giants like Apple and Google.

As hyperscale operators race to deploy increasingly powerful infrastructure, the thermal limits of traditional data centers are being tested, triggering a massive surge in demand for advanced cooling technologies…

The rapid adoption of high-performance computing (HPC) and AI workloads is forcing the industry to move beyond conventional air-cooling methods toward liquid and hybrid architectures capable of managing extreme thermal densities.

We also need to talk about water consumption in chip manufacturing. Large data centers can contain tens of thousands of servers, each with multiple chips. During the manufacturing process, ultrapure water is ideal for cleaning, etching and rinsing chips. But creating ultrapure water is itself highly water intensive. It takes about 1,500 gallons of piped water to produce 1,000 gallons of ultrapure water. An average chip manufacturing facility consumes about 10 million gallons of ultrapure water per day.

Mineral usage

The physical infrastructure of data centers requires significant land and raw materials, including copper and silver, and rare earth elements for manufacturing chips.

The IEA says one of the most vulnerable areas to energy security is critical minerals supply chains. “The key risk for critical minerals is high levels of market concentration,” the agency wrote, noting that China is the dominant refiner for 19 out of 20 energy-related strategic minerals.

Such minerals are vital for power grids, batteries, EVs, AI chips, jet engines, defense systems and other strategic industries. As of November 2025, more than half of these strategic minerals are subject to some form of export controls.

Two minerals of concern are copper and silver.

Copper is not only vital to electrification but to artificial intelligence and the infrastructure that supports AI. Copper is used in computer chips, EVs, and in the reams of wiring required by data centers.

Due to unexpected closures and operational interruptions, such as the mud intrusion that shut down the world’s second-largest copper mine, Grasberg in Indonesia, the copper market this year is in a deficit. The shortfall is expected to deepen in 2026.

There has been a dearth of new copper discoveries in recent years, and the grades of existing copper mines are dropping, which, when added to operational misses, are making the supply problem worse.

Earlier this year, copper shipments were frontloaded to the US ahead of an expected tariff on the metals.

A combination of strong demand and limited supply has vaulted the copper price to record highs above $5 a pound.

A big variable is demand from data center growth, which could translate into a 30% increase in copper demand by data centers next year, writes Gregory Shearer, head of base and precious metals strategy at JPMorgan, via Axios.

At U.S. Global Investors, Frank Holmes writes A conventional data center uses between 5,000 and 15,000 tons of copper. A hyperscale data center, on the other hand—the kind being built to run artificial intelligence (AI)—can require up to 50,000 tons of copper per facility, according to the Copper Development Association…

Data centers currently consume about 1.5% of global electricity supply, roughly the same amount as the entire U.K., according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). The organization believes that, by 2030, demand will more than double, with AI responsible for much of the increase. That means data centers could be consuming more than half a million metric tons of copper annually by the end of the decade.

Perhaps even more significant is Holmes’ remark that data centers are largely indifferent to copper prices. Despite the amount of copper in data centers, the cost is low. According to Wood Mackenzie, the metal accounts for just 0.5% of total project costs. That means data centers will be built whether copper is trading for $10/lb or $20/lb.

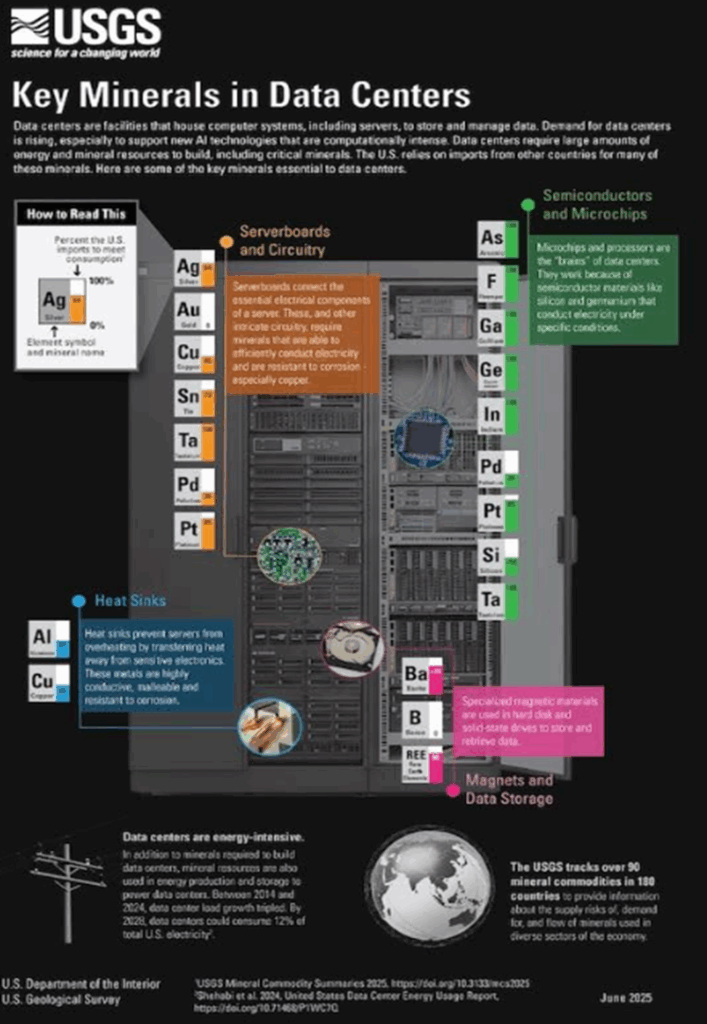

The excellent graphic below by the US Geological Survey summarizes the key minerals used in a data center. The percent inside each mineral “box” refers to the percent the US imports to meet consumption for that mineral.

Source: USGS

Server boards that connect the electrical components of a server and other intricate circuitry require minerals that efficiently conduct electricity and are resistant to corrosion — especially copper but also silver, gold, tin, tantalum, platinum and palladium.

Metals used in heat sinks that prevent servers from overheating include aluminum and copper.

Microchips and processors work because of semiconductor materials like silicon and germanium that conduct electricity under specific conditions. Other metals include arsenic, fluorspar, gallium, indium, palladium, platinum and tantalum.

Specialized magnetic materials are used in hard disk and solid-state drives to store and retrieve data. Minerals include barite, boron and rare earths.

Conclusion

Data centers get a mixed review by us at Ahead of the Herd.

In a world of scarce resources, data centers threaten to create shortages of electricity, water, and key minerals needed for the electrification transition, especially copper and silver, which are already seeing market deficits.

It’s worth repeating Frank Holmes’ comments on data centers and copper usage:

A hyperscale data center—the kind being built to run artificial intelligence (AI)—can require up to 50,000 tons of copper per facility, according to the Copper Development Association.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) believes that, by 2030, demand will more than double, with AI responsible for much of the increase. That means data centers could be consuming more than half a million tonnes of copper annually by the end of the decade.

An additional half-million tonnes doesn’t seem like a lot, but it will stretch miners to find that extra copper. Global mined copper production is about 22 million tonnes a year, but a shortfall of 30% is expected by 2035. There are few new copper mines being built and the ones that are usually have offtakes with Asian countries, not Western ones.

The most exigent threat to resources is power usage. BloombergNEF sees power demand from data centers reaching 106 gigwatts by 2035, which is a 36% upward revision from its April outlook. One gigawatt can power 750,000 to a million homes, so 106 GW powers up to 106 million homes. That’s nearly the entire housing stock of the United States — 148 million housing units as of the late 2024/early 2025, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Data centers proliferating across the US will require 22% more grid power by the end of 2025 than they did in 2024 and will need nearly three times as much in 2030, according to the most recent forecast from 451 Research, part of S&P Global.

Where are we going to find the power? We’ve already dammed practically every river in North America, coal usage is on the outs, and natural gas, while a bridge fuel, is from a lifecycle perspective as polluting as coal, if not worse. Fracking natural gas wells, putting the gas into a pipeline, then shipping it hundreds of kilometers to a liquefaction facility that turns it into LNG using natural gas-fired turbines is not green.

Nuclear is a solid option but it takes years to permit and build a conventional nuclear power plant. Small modular reactors are a possibility, but they are in their infancy.

Small modular reactors gaining traction, powered by AI

Renewables aren’t recommended due to the intermittency factor. Data centers need power 24/7/365.

Large data centers can consume up to 5 million gallons per day, equivalent to the water use of a town populated by 10,000 to 50,000 people. In drought-prone areas, data centers are not a good idea; they threaten to gobble up precious water supplies for residents and farmers.

The siting of data centers hasn’t been well-planned, Nearly 7,000 of the world’s 8,808 data centers sit outside the recommended temperature range. Around 600 are sited in areas with average temperatures above 27C, meaning they require more cooling, and more water.

A significant portion of data center water consumption is derived from steam-generating plants. Large boilers filled with water are heated with natural gas or coal to produce steam, which runs a turbine to generate electricity.

Of course, all of this strain on resources is if the data centers planned actually get built. This many not actually be the case. Lately there has been skepticism in the market about the future of AI. Oracle’s stock sold off when it was announced that a key financer of its planned $10-billion data center wouldn’t back the data center to be located in Michigan.

In Texas, speculative projects are clogging up the pipeline to connect to the electric grid, making it difficult to see how much demand will actually materialize. But investors will be left on the hook if inflated demand forecasts lead to more infrastructure being built than is actually needed.

In other words, there is a risk of stranded assets.

There is also the risk of a bubble forming around data centers and AI.

Tech companies are issuing too much debt, posing a potential threat to the financial system and the broader economy.

Fortune magazine reports that, even after adjusting for inflation, tech companies are issuing more corporate bonds than during the dot-com boom of the 1990s.

If the trillions in economic activity promised by AI and carried out be data centers does not materialize, many investors will lose their shirts.

Many observers have compared AI to the dot-com boom of the 1990s. In fact, it’s worse. A Moody’s economist says the dot-com era debt was different because internet companies didn’t carry a lot of debt; instead, they were funded by stocks and venture capital. That’s not the case with the AI boom; companies are heavily leveraged, and while some are making huge revenues, others aren’t. The industry is heavily bifurcated between those generating massive revenue (primarily infrastructure providers) and those struggling to turn that revenue into profit due to high operational costs, states an AI Overview.

One disturbing trend is the “circular economy” among major players, which involves investing in, renting from, and supplying each other.

For example, Nvidia invests in OpenAI, which buys cloud computing from Oracle, which in turn buys chips from Nvidia.

Smaller data center operators like CoreWeave and TeraWulf are borrowing heavily (at interest rates up to 9%) to build infrastructure, which is then rented out to larger firms like OpenAI.

CNBC reports investors are facing a risky and highly concentrated US stock market going into 2026, with the “Magnificent 7” representing as much as 35% to 40% of the S&P 500 in mid-December trading.

If the AI bubble pops, investors are in for a world of pain.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.