Critical minerals supply diversification remains a daunting task – Richard Mills

2023.07.14

When it comes to the diversity and reliability of critical mineral supplies, it appears the Western economies still have lots of ground to make up.

According to the International Energy Agency, the concentration of supply intensified for some critical minerals in 2022 despite US and Europe’s efforts to diversify and reduce reliance on China.

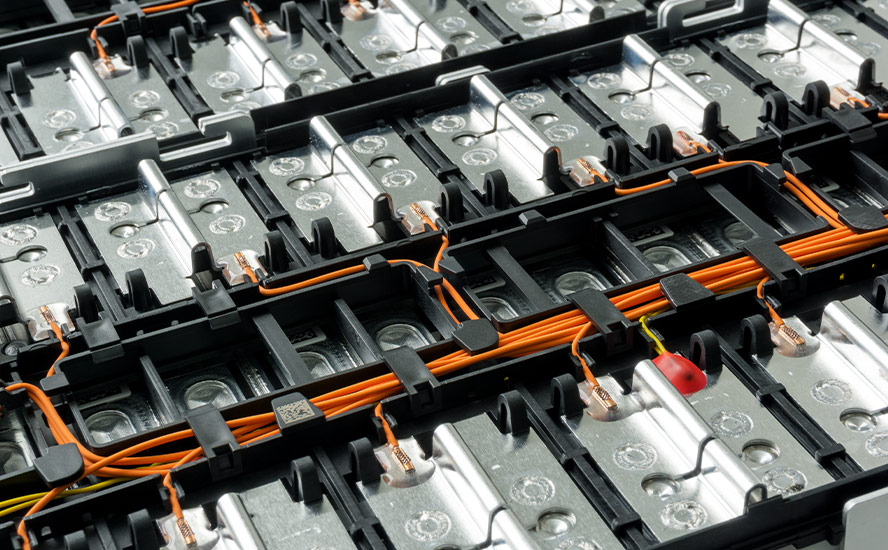

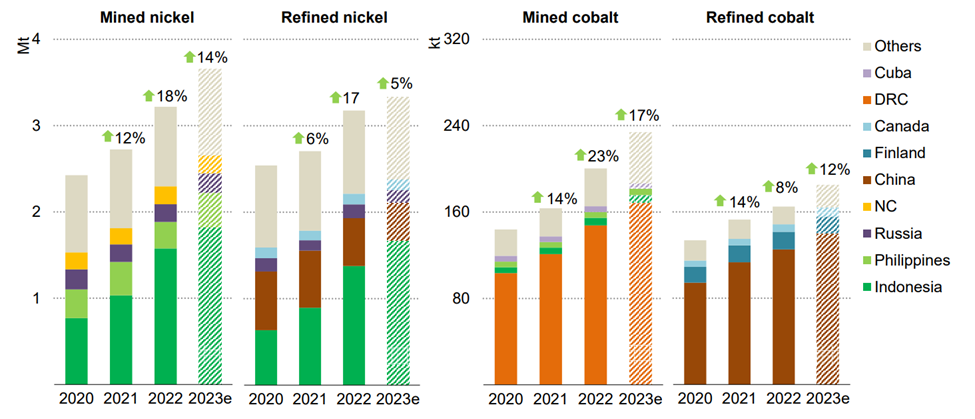

The minerals in question — as highlighted by the IEA’s 2023 edition of the Critical Minerals Market Review — include nickel and cobalt, key ingredients in EV batteries whose supply sources are heavily concentrated.

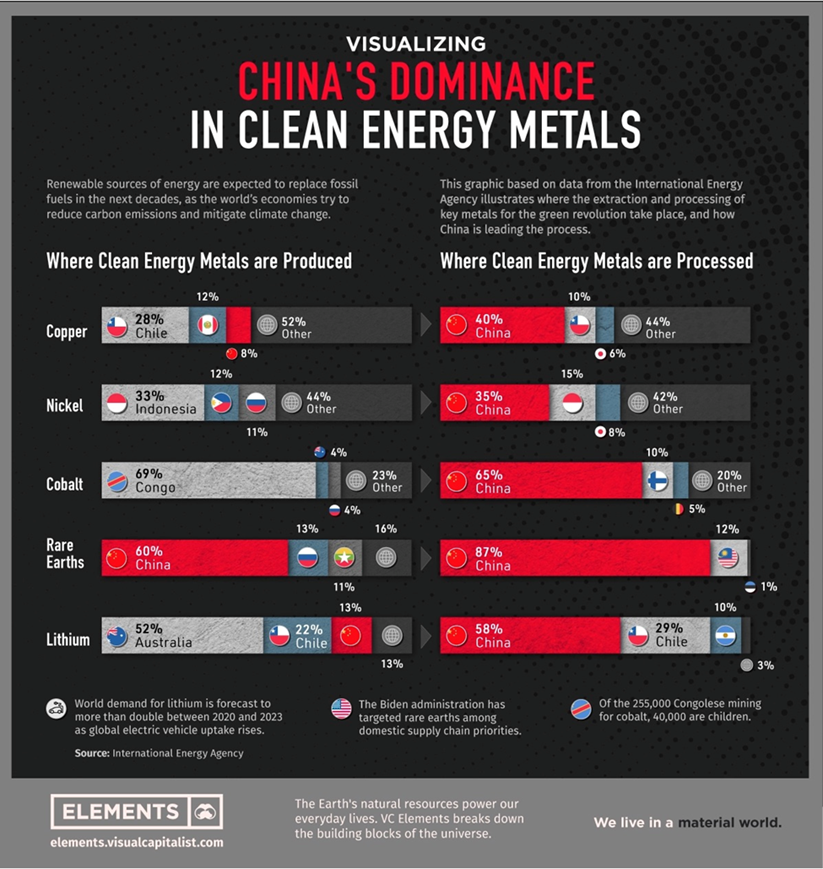

Nearly 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, while about a third of nickel production is credited to Indonesia. China controls a majority of the metals processing business, establishing itself as the dominant force in the battery metals supply chain.

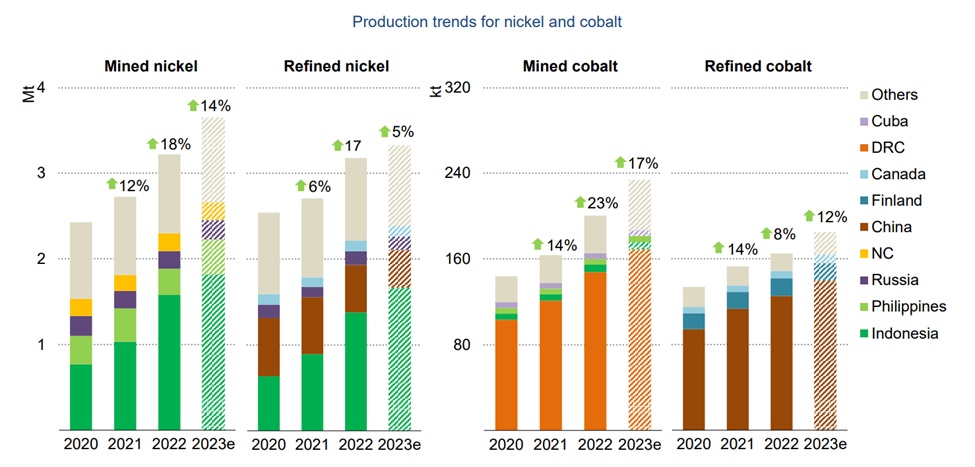

For both metals, the 2023 IEA report found that the share of the top three producers last year either remained unchanged or has increased further compared with 2019 (see graphic below).

“Our analysis of project pipelines reveals a somewhat improved outlook for mining, but not for refining operations where today’s geographical concentration is greater,” the agency stated.

Planned projects are mostly developed in incumbent regions, with China holding half of planned lithium chemical facilities and Indonesia representing nearly 90% of planned refined nickel plants, the IEA said.

“Many resource-holding nations are seeking positions further up the value chain while many consuming countries want to diversify their source of refined metal supplies. However, the world has not yet successfully connected the dots to build diversified midstream supply chains,” it added.

One conclusion we can draw from this is that both the US and Europe still have a long way to go before they can disburden themselves from rival nations, specifically China — the across-the-board leader in battery metals processing (see below).

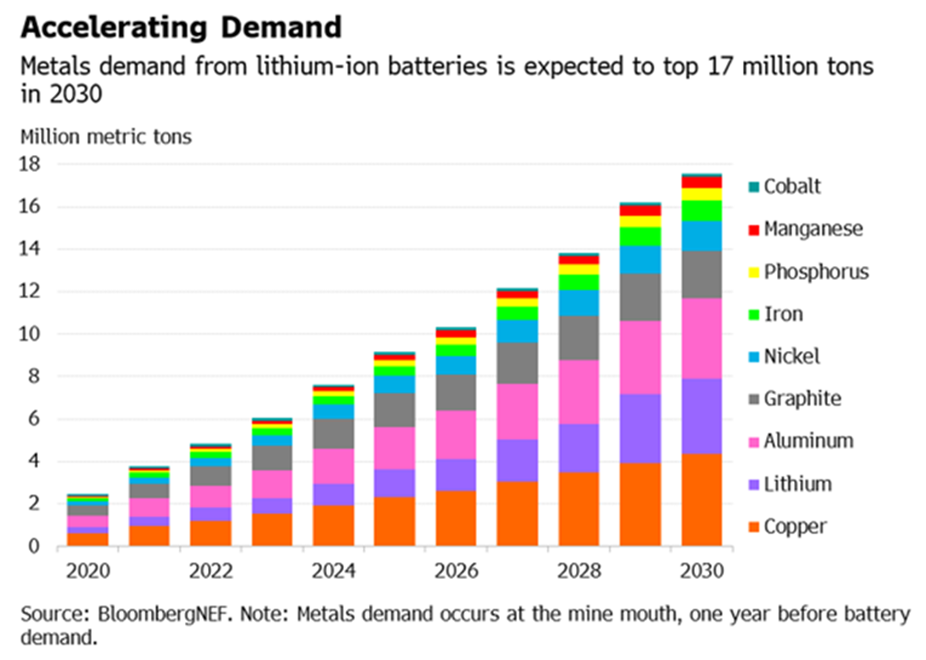

The urgency to diversify the supply chain has never been greater, given the unprecedented level of demand growth expected for minerals like copper, lithium, graphite, nickel etc. that are required to tackle climate change.

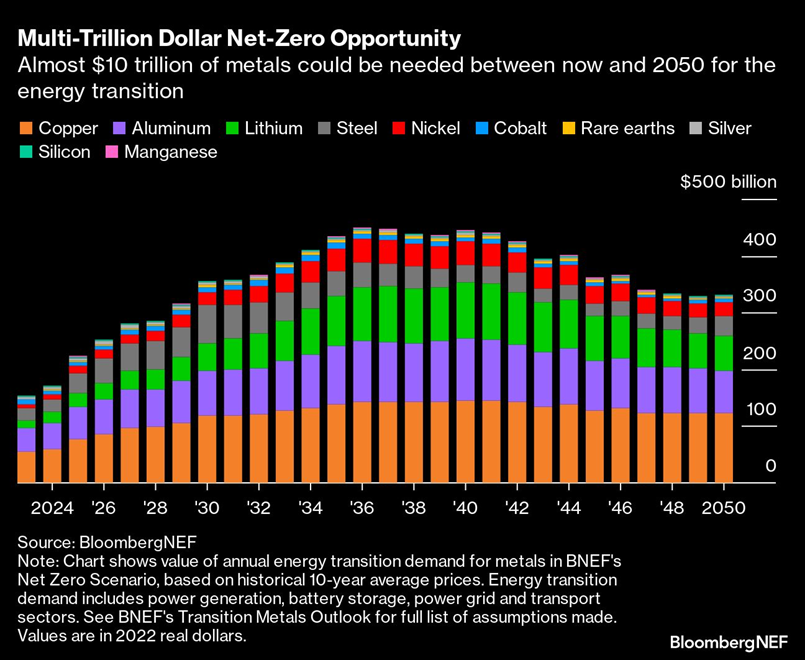

BloombergNEF estimates that getting to our net zero climate targets could require almost $10 trillion worth of metals between now and 2050, with annual demand peaking at close to $450 billion in the mid-2030s.

To reach net-zero, demand for these key metals needed for the deployment of energy transition technologies such as solar, wind, batteries and electric vehicles will grow fivefold by 2050, BNEF says.

To meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, IEA data previously showed that sectors contributing to the green energy transition will be responsible for over 45% of the total copper demand, 61% of the nickel demand, 69% of the cobalt demand, and a whopping 92% of lithium demand by 2040.

This unprecedented level of consumption would eventually overwhelm our existing supply of metals. Should production fail to catch up, sooner or later, the world could be facing a severe metals shortage that endangers the energy transition.

Graphite Gaining Traction

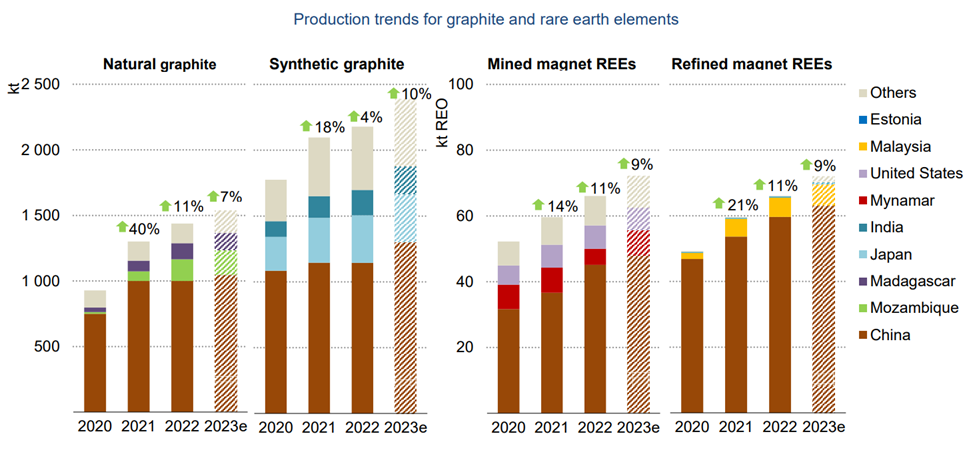

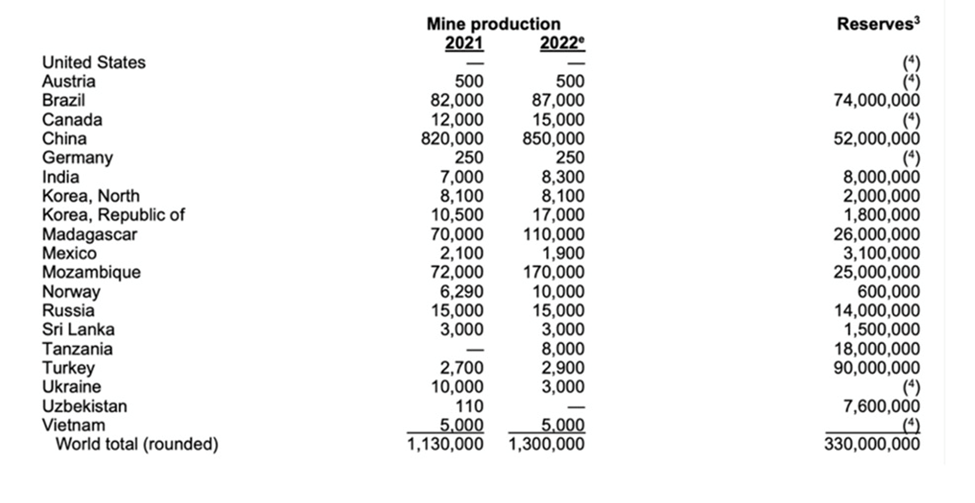

A mineral that’s gaining more traction in the critical minerals discussion is graphite, as its supply in clean energy applications is pretty much monopolized by China.

While graphite is a material that’s used in multiple industries, from refractory material to lubricant, demand is growing the fastest in the EV battery sector. According to the USGS, the battery end-use market for graphite has grown by 250% globally since 2018.

The World Bank estimates that graphite accounts for over half (53.8%) of the mineral demand in batteries, the most of any. Lithium, despite being a staple across all batteries, accounts for only 4% of total demand.

This is because graphite is the only suitable anode material and is the largest component in batteries by weight, constituting 45% or more of the cell. There is nearly 4 times more graphite feedstock consumed in each battery cell than lithium and 9 times more than cobalt.

An average plug-in EV nowadays can contain up to 70 kg of graphite.

Graphite can be sourced from natural deposits or produced artificially. Some 70% of the natural flake graphite in 2022 was supplied by China, which is also the main producer of synthetic graphite and anodes. The process to make spherical graphite that is used for batteries takes place almost entirely in China.

Battery producers have favoured synthetic graphite for its greater reliability, leading to longer battery longevity. Almost 80% of anodes manufactured in China are made using synthetic graphite. But production requires coke and temperature above 2500° C, leading to considerable CO2 emissions.

On the other hand, natural graphite is cheaper and less energy-intensive to produce. Thanks to technological development, the reliability of natural graphite quality has been improving over the past few years. For these reasons, the market share of natural graphite is expected to increase in the coming years, the IEA predicts.

For the United States, graphite represents a key area of vulnerability because it has zero domestic production of the mineral and is 100% reliant on imports.

According to the USGS, in 2022 the US imported 82,000 tonnes of natural graphite, of which 77% was flake and high-purity. The top importers were China (33%), Mexico (18%), Canada (17%) and Madagascar (10%).

But taking into account the fact that EV batteries require run-of-mine graphite to go through purification and coating, a process controlled by China, the US was actually not 33% dependent on China for its battery-grade graphite, but 100%. This is a precarious position to be in should the country want to stay in contention for EV dominance.

Graphite Demand Catching Up

Things get worse for the US (and other net importers) when you factor in the rapidly growing demand for critical minerals like graphite.

BloombergNEF forecasts graphite demand to quadruple by 2030 on the back of an EV battery boom. The IEA goes 10 years further out, predicting that graphite demand could see an 8- to 25-fold increase between 2020-2040, trailing only lithium in demand growth upside.

For natural graphite alone, it’s thought that battery demand could gobble up well over 1.6 million tonnes of output per year. However, this figure will likely grow each year as expected, posing a serious threat to the global supply chain as the material is already used in a variety of industries.

For context, the 2022 mine supply was about 1.3 million tonnes, which means we’re very close to entering, if not already, a period of market deficits.

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence projects that natural graphite will have the largest supply shortfalls of all battery materials by 2030, with demand outstripping expected supplies by about 1.2 million tonnes.

And this is just counting EV battery use only; the mining industry still needs to supply other end-users. The automotive and steel industries remain the largest consumers of graphite today, with demand across both rising at 5% per annum.

BMI has said as many as 97 average-sized graphite mines need to come online by 2035 to meet global demand.

Alaska’s Graphite Creek Project

Without any graphite mines, the US is already falling way behind the pack. So far, the US government has only identified 10 sites that include mineral regions, mineral occurrences, and mine features that contain enrichments of graphite.

The largest of those, as determined by the USGS, is the Graphite Creek deposit in Alaska, containing a measured and indicated resource of 37.6 million tonnes grading 5.14% Cg (graphitic carbon) for 1.93 million tonnes of natural graphite. It also has 243.7 million tonnes of inferred resources at 5.07% Cg, for another 12.3 million tonnes of natural graphite.

The deposit is being developed by Vancouver-based Graphite One (TSXV:GPH, OTCQX:GPHOF) as part of its Graphite Creek property situated along the northern flank of the Kigluaik Mountains, spanning a total of 18 km.

In early 2021, Graphite Creek was given High-Priority Infrastructure Project (HPIP) status by the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Committee (FPISC), which would help streamline its permitting process and fast-track the mine to production.

Once up and running, it would produce, on average, 51,813 tonnes per year of graphite concentrate during a projected 23-year mine life. The company itself would produce about 75,000 tonnes of products a year, of which 49,600 tonnes would be anode materials, 7,400 tonnes purified graphite products, and 18,000 tonnes unpurified graphite products.

These figures, mind you, are based on the exploration of only one square kilometer of the 16-km deposit, meaning that it could easily crank up production by a factor several times the current (proposed) run rate of 2,860 tonnes per day.

The mine represents just the first link in Graphite One’s plans to become a fully integrated producer serving the nascent EV battery market. Anchored by its Graphite Creek resource, the company has also proposed the construction and operation of a graphite material manufacturing facility in Washington State.

This will be followed by a recycling facility to be co-located at the Washington plant, completing the third and final link in its “circular economy” strategy.

Nickel Remains Concentrated

Nickel, another vital raw material in electric vehicles, is also in a tough spot despite rising production, as it’s probably facing the largest absolute demand increase among all battery metals, the IEA stated in a report last year.

As many as 60 new nickel mines would be needed by 2030 to meet global net carbon emissions goals, the IEA estimates. BHP, the world’s biggest miner, expects global demand for nickel to grow as much as fourfold over the next 30 years as electric vehicles almost entirely replace traditional cars.

Nickel metal is classified into two categories based on their respective purities. Class 1 nickel is primarily used for battery cathodes and is sourced from Russia, Canada and Australia, while Class 2 nickel, used for industrial alloys, is mainly supplied by Indonesia, the Philippines and New Caledonia.

In 2022, the industry added a record amount of supply, with mined nickel production up by 18% and refined nickel production up by 17%, the IEA estimates in its 2023 report.

This surge in supply was primarily driven by Indonesia, which experienced a staggering 50% growth in both mined and refined nickel supplies, putting the market balance into surplus.

Adding to its established position as the world’s largest nickel miner, the country overtook China as the largest refined nickel producer, though many of the new capacities were financed by Chinese companies.

About 90% of new nickel refining projects tracked by the IEA are now found in Indonesia.

While Indonesia remains the leading producer of Class 2 nickel, its joint venture with Chinese companies in high-pressure acid leach (HPAL) plants is enabling the processing of its laterite resources into Class 1 products.

The conversion of nickel pig iron (NPI) into nickel matte, which can be further refined into battery-grade nickel, is also coming to fruition. The ramp-up of nickel processing in Indonesia is expected to continue, with the country having a number of additional HPAL plants in the pipeline.

Surimeau Property in Quebec

Several new nickel development projects are currently underway outside of Indonesia, particularly in Australia and Canada.

One of those is the district-scale polymetallic property being developed by Renforth Resources (CSE:RFR, OTCQB:RFHRF, FSE:9RR) in the Canadian province of Quebec. Its Surimeau property, which is still relatively underexplored, hosts several areas prospective for gold/silver and battery/industrial metals (nickel, copper, zinc, lead, cobalt, lithium and manganese). To date, about 29 kilometers of surface mineralization has been defined.

For the better part of two years, Renforth’s exploration focus has been on the more advanced Victoria mineralized battery metals horizon and parts of the longer Lalonde horizon lying parallel to the north.

Victoria is a ~20km long “ground truth” magnetic structure bearing nickel, copper, zinc and cobalt mineralization at surface. It stretches between the Victoria West mineralization, which has been drilled over 2.2 km in the west, and the Colonie mineralization, drilled and surface sampled by Renforth in the east.

The company interprets Victoria’s geological setting to be similar to the Outokumpu polymetallic district in eastern Finland, which hosts a rare style of mineralization that hosts a sulfide nickel magmatic sulfide deposit juxtaposed with a copper-zinc massive sulfide deposit.

The Lalonde mineralization, located ~3 km north of Victoria West, was only recently drilled by Renforth. This surface mineralized system, similar to Victoria, currently stretches over ~9 km of ground-truthed strike.

Both zones are about 250-500 metres in thickness, running east-west across the central portion of the property. The two systems are interpreted by Renforth as two arms of a fold, with the fold nose located off the property and to the east.

The company has already commenced modelling the central Victoria area, where it has completed the most work, in order to determine whether an initial resource can be calculated over this limited area.

Copper Shortages

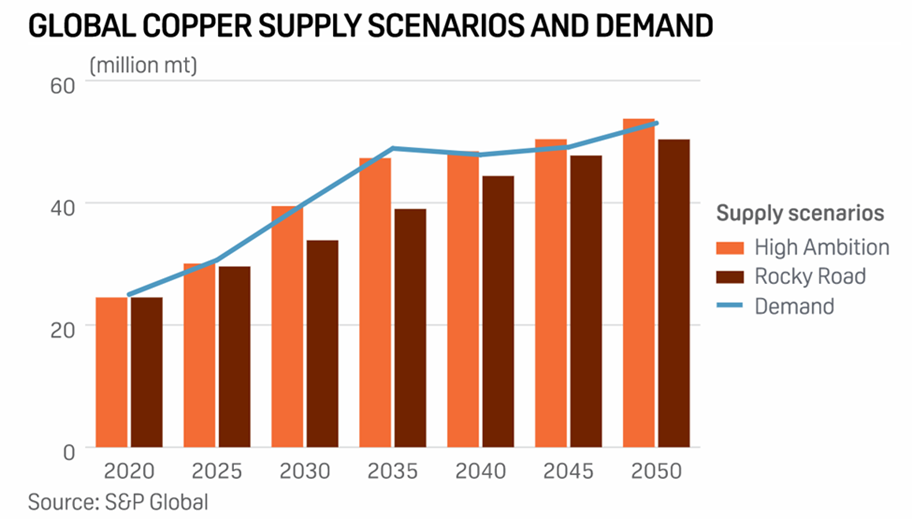

In terms of the overall impact on the energy economy, copper is arguably the most important metal, and it has a much larger market than lithium, nickel and cobalt given its broad applications in the renewables and EV sectors.

As expected, demand for copper will continuously rise in the coming years. BloombergNEF estimates that copper demand, driven by various clean energy initiatives, will grow 53% to 39 million metric tons by 2040.

Analysts at S&P Global are expecting an even quicker and bigger jump, with copper demand set to double to 50 million metric tonnes by 2035.

In a scenario that meets the Paris Agreement goals (as in the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario), the energy sector’s share of total demand must rise significantly over the next two decades to over 40% for copper.

However, looking further ahead in a scenario consistent with climate goals, the expected supply from existing mines and projects under construction is estimated to meet only 80% of the world’s copper needs by 2030, the IEA says.

According to consulting firm McKinsey, electrification is expected to create a 6.5 million ton shortfall at the start of the next decade, highlighting a substantial output gap that the mining industry has to address.

Therefore, new copper mines must be built, and in a timely manner, to close this gap. But this may be easier said than done. Among the issues impeding new supply are lower ore grades, depletion of existing mines, a lack of new discoveries, and resource nationalism in three of the main copper-producing countries: Chile, Peru, and the DRC.

Such risks further highlight the importance of copper supply diversification.

Copper Discoveries in Colombia

One country that has the potential to rise up the ranks is Colombia, which shares the geological advantages of the Andes, plus the mineral-rich basins previously explored for petroleum and known for their large coal reserves.

Situated along the copper-rich Cesar basin of northeastern Colombia is a massive property held by Max Resource Corp. (TSX.V: MAX; OTC: MXROF; Frankfurt: M1D2), whose mining concessions collectively span over 188 square kilometers, representing the largest area prospective for copper in the prolific sedimentary basin.

The Cesar Basin has a simplified Jurassic-Triassic stratigraphy, characterized by Cu-Mo-Au porphyry and porphyry-related vein systems in the upper levels and sediment-hosted style Cu-Ag deposits lower down.

Max’s CESAR property is divided between three major copper-silver zones (AM, Conejo & URU) individually located along a 90 km long belt.

The sediment-hosted stratiform copper-silver mineralization found in the southern end (URU and Conejo zones) of its Cesar project is interpreted to be analogous to the Central African Copper Belt (CACB), while the northern end (AM zone) is compared to the Kupferschiefer deposits in Poland.

It’s estimated that nearly 50% of the copper known to exist in sediment-hosted deposits is contained in the CACB, headlined by Ivanhoe Mines’ 95-billion-pound Kamoa-Kakula discovery in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Kupferschiefer, meanwhile, is considered to be the world’s largest silver producer and Europe’s largest copper source.

This year, Max is undertaking a two-pronged approach to exploration on its CESAR project: 1) To evaluate and prioritize existing targets within its mining concessions for drill testing; and 2) continue the regional sampling and prospecting program to identify additional targets along the 90-km long mineral belt.

Conclusion

Diversification of the critical minerals supply remains a daunting task for the global energy transition.

Despite heavy Investment in the mining industry — which has seen a jump of 50% over the past two years — production of certain minerals remains heavily concentrated within certain geographies, the IEA’s 2023 report showed.

Two years ago, the agency warned that booming demand for critical minerals during the energy transition risked creating huge shortages of critical raw materials like lithium, cobalt, copper and nickel.

And while the shortages, according to IEA, are likely to ease in the coming years after the investment surge, the geographical concentration, especially in terms of refining and processing the metals, remains a huge area of concern.

Graphite is a good example, where the US could easily be cut off the supply chain by its main rival China, who controls most of the mine production and nearly 100% of the mineral processing. China’s recent export controls on gallium and germanium serve as a good reminder that it’s always ready to pull the plug on its wealth of minerals.

So, new graphite mines (or any other critical mineral for that matter) need to be developed in places that aren’t historically known to produce them, but have the potential to do so.

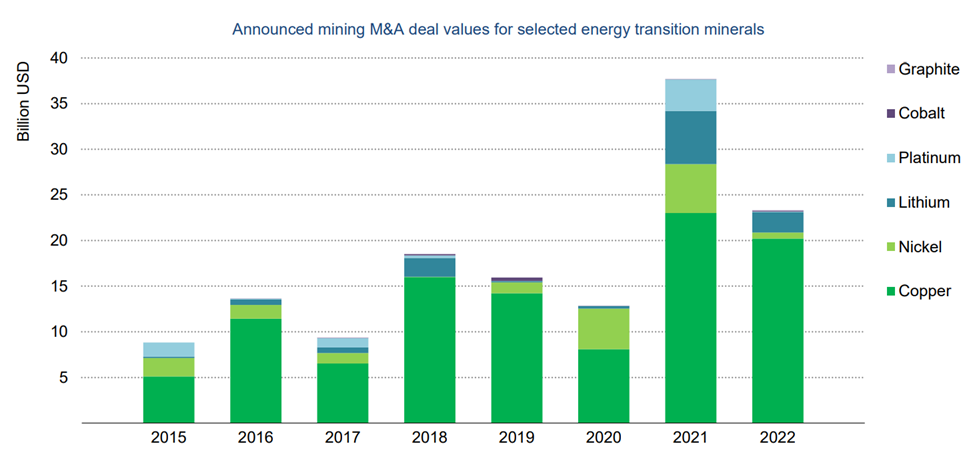

Aligning with the supply diversification theme, the IEA found that the mining industry has been allocating a greater amount of capital to new developments, exploration, and mergers and acquisitions over the past couple of years (see graph below).

“We look at the situation after raising alarm bells, and we are of the view that governments and companies have responded to this rather challenging situation,” Fatih Birol, the head of the IEA, said in an interview.

“We all know that mining projects often face delays — there are permitting issues and cost overruns — but the picture from an investment point of view is rather encouraging.”

It goes without saying, though, that investments must go to the right projects.

In this article we highlighted three mining companies and their flagship projects targeting energy transition metals. We believe these projects could easily be scaled up to what the majors require, and it’s up to the industry to capitalize on them.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.