Buy signal flashing for undervalued commodities

2022.08.23

Inflation is at a 40-year high, making commodities, which protect investments from rising prices and currency debasement, a good place to park your hard-earned cash.

There are many reasons to be bullish on commodities and, a lot to indicate that inflation is not going away anytime soon, thus setting up the conditions for a multi-year commodities up-trend.

First, there has been a lack of spending on exploration and development, leading to current and looming supply shortages for a number of metals. The mining companies in the mid-2010s basically ate each other and by shutting down exploration there was no accretive increase in reserves. Lower ore grades have also become an issue.

Second, natural resources are being used up faster than they can be replenished; this is another theme driving commodity prices higher.

Third, countries that have the metals needed to fuel economic growth are guarding them more closely than previously; resource nationalism is on the rise.

Fourth, the United States, China and the European Union need to invest heavily in infrastructure and mining, especially critical minerals needed for the shift toward electrification and decarbonization.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates the transition will require about $173 trillion in investments over the next three decades, gobbling up practically every mined commodity under the sun.

Below we lay out our investment case for commodities.

Commodities do well in recessions

It may seem illogical to even consider commodities during current market conditions.

Both the energy and materials sectors are considered very economically sensitive, exemplified by oil pulling back almost 30% from its June high of $120 per barrel, and a sharp reduction in the price of copper, the metal with a “PhD in economics”, suggesting a recession is looming. From its March 2022 high of $5.00 a pound, spot copper has drifted down to $3.64, as of this writing on Friday, Aug. 19.

Industrial metals aluminum, zinc and lead have all seen similar declines, with investors shying away due to the threat of a global economic downturn or even stagflation, a particularly nasty combination of high inflation, unemployment and low economic growth.

Another reason metals have been selling off, is investors looking back at the Great Recession of 2007-09 as a guide. The recession was notoriously bad for commodities. Materials and energy were two of the worst sectors in the S&P 500, crumbling 60% between May 2008 and March 2009. When traders and investors heard calls for recession a few months ago, these areas were once again targeted for liquidation. From June 8 to July 12, materials and energy fell 15-25%.

It’s a decision they may live to regret. Using the 2008 playbook risks selling commodities at the bottom of a cycle, missing huge potential returns over the coming decade.

That’s because, when investing in natural resource equities, the commodity capital cycle is more important than the broader economic cycle. If that sounds confusing, all will become clear, after I explain the chart below, that I found in a recent report from Goehring & Rozencwajg, the Wall Street natural resource investment firm.

The chart shows the relationship between the Dow Jones Industrial Average and a commodity index going back several decades. It clearly indicates periods when commodities are extremely undervalued or overvalued – compared to the Dow. In places where the green line falls under 75, commodities are cheap relative to financial assets. These periods typically represent bear markets for commodities. The chart shows the most undervalued years for commodities were 1929, 1969, 1999 and 2020.

The following chart by Schroders is similar to G&R’s but tags key events at points in time when commodities have been overvalued.

What makes commodities cheap, relative to financial assets? According to Goehring & Rozencwajg (G&R), it has to do with natural resource capital spending:

A commodity price cycle usually follows a typical path. The industry might enjoy a period of very high energy or metal prices. Given their fixed cost base, the higher commodity prices fall directly to the bottom line resulting in a period of super-normal profits. High returns attract new capital and before long the industry begins a new cycle of exploration and development. Over time, increased spending leads to new supply which eventually outpaces demand growth and ushers in a period of commodity surplus. Prices fall, causing projects that were underwritten at higher prices to become impaired and written off. Often, another industry or investment strategy falls into favor around this time and investors rush to reallocate capital towards hot new speculative areas, leaving the resource industry even more capital starved. As depletion takes hold, supply falters, demand grows, and inventory gluts eventually get worked off. The stage is set for the next bullish cycle to start.

Their advice is to buy resource stocks when commodities are cheap, and during bottoms in the natural resource capital investment cycle.

The key point is that for most of the past 120 years, the commodity cycle and the business cycle (referring to expansions and recessions) have not been in sync. In fact throughout the 20th century, resource stocks have been good investments during recessions.

The Great Recession was actually an anomaly, when the two trends were in near-perfect alignment. In early 2008 commodity prices were extremely high relative to the stock market. Driven by insatiable demand from China, commodities were enjoying a “super-cycle”. Moreover, capital spending in the S&P 500 surged four-fold between 2000 and 2008 from $80 billion to an all-time high of $330 billion per year, according to the G&R report. Referring to the above chart, this was a period of extreme commodities overvaluation, with the green line touching 250. It set the stage for a massive correction to commodities when the recession arrived.

Let us now evaluate the current situation with respect to commodities, with the Commodity Prices/ Dow Jones Industrial Average chart.

Notice that commodities are extremely undervalued when the green line dips below the black line indicating a value of 75. In 1930, for example, when the Great Depression started, from 1954 to 1972 — a very long bear market for commodities — in 1999, and from about 2015 to 2020.

Right after the dips though, the green line shoots higher. We see this most prevalently in 1932, 1973, 1981, 1991 and 2008. Commodity prices are seen drifting lower for about a decade from 2010, reaching a nadir with the coronavirus economic crisis of early 2020.

But as we know from recent history, economic recovery from the pandemic, combined with trillions worth of direct and indirect government stimulus, pushed demand for goods and services higher than supply, creating a boon for commodities along with the highest levels of inflation in 40 years. This is represented by the slight uptick on the right of the chart.

The key point is that even if we were to go into another recession, it doesn’t necessarily mean that commodity prices will fall in lockstep, as they did in 2008. In fact, they (and resource equities) are likely to hold their own and do quite well, because unlike in 2008, commodities are undervalued, shown on the chart as the green line falling below 75 in 2015 and staying there until 2020, when they began trending up again.

In terms of G&R’s commodity capital cycle described above, we are currently in the stage of depletion, when supply falters, demand grows, and inventory gluts gets worked off. The stage is, imo, set for the next bullish cycle to start.

In their report, G&R maintain that The radical undervaluation of commodities and commodity related equities is greater now than it was back in 1929, and the level of capital starvation is just as great. History tells us that commodities could again be an excellent place to seek high returns, even if the 2020s experience a period of economic turmoil as severe as the Great Depression — a scenario we consider unlikely.

Under-investment

I’ll say more about this “capital starvation” because it’s key to understanding what is happening with commodities right now.

As a result of the bear market in commodities from 2010-20, capital spending for the extractive industries — mining and oil and gas — has been severely curtailed. For example in the energy sector, capital spending in the S&P 500 has plummeted from $320 billion per year to less than $100B currently.

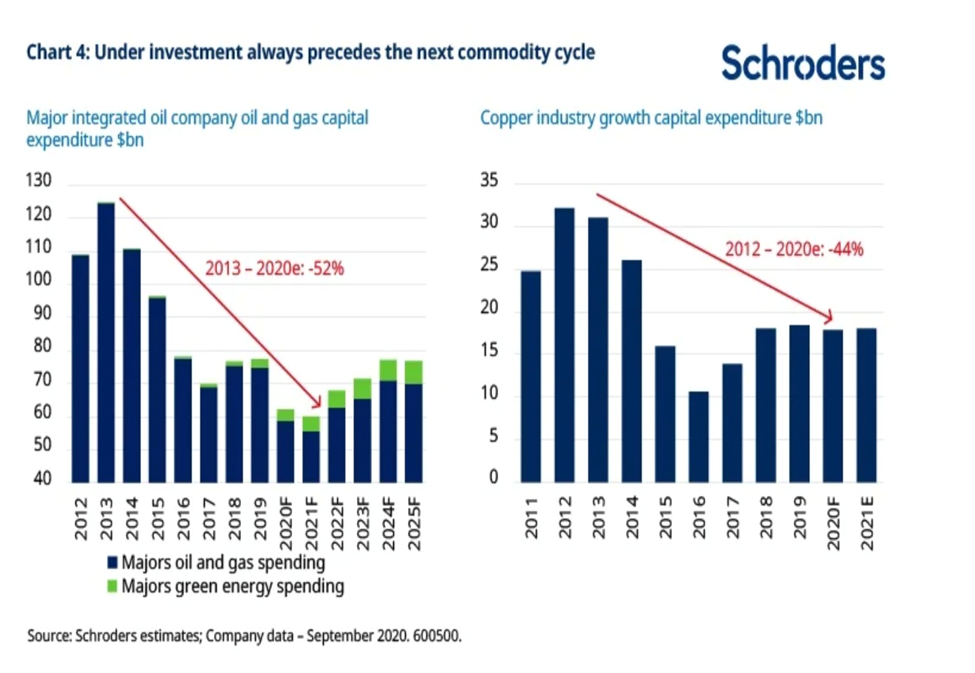

Another source found that capex in oil and gas and mining has fallen by about 40% since 2011. The 2021 article by Schroders notes that under-investment always precedes the next commodity cycle, with the chart below showing that capital investments in major integrated oil and gas companies declined by 52% between 2013 and 2020, and capex in the copper industry dropped by 44% between 2012 and 2020.

(The latter aligns with our research. As previously reported, global mined copper production will drop from the current 20Mt to below 12Mt by 2034, resulting in a supply shortfall of 15Mt. By then, over 200 copper mines are expected to run out of ore, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place. S&P Global estimates that new copper discoveries have fallen by 80% since 2010.)

More about under-investment in the mining industry comes via the Wall Street Journal, which reported last year that Despite a commodity boom that is boosting profits, miners aren’t throwing cash at new projects, raising concerns about future shortages of some metals.

Faced with investor memories of billion-dollar write-downs and share price implosion during the commodities bear market of 2010 to 2020, a lot of mining companies have been reluctant to invest in new projects, preferring to plow profits into higher dividend payouts. That hesitancy to invest is raising the specter of supply crunches, notes WSJ, with “pinch points” appearing in energy-transition metals such as copper and platinum group metals, or PGMs.

Analysts say that spending across the industry isn’t keeping pace with demand and is expected to lead to shortfalls for many resources — something we at AOTH have been talking about for years.

According to investment bank Liberum, in 2020, the $75 billion spent by 45 of the world’s largest miners was a third lower than in 2012, while dividends were 125% higher.

In our last article we mentioned the International Energy Agency’s eye-opening study warning that the world needs to significantly increase its supply of metals that are essential to clean technologies. We’re talking about up to six times more than what we’re producing today. The Paris-based energy watchdog also said expected supply from existing mines and projects under construction is estimated to meet only half of lithium and and cobalt requirements by 2030.

“Today, the data shows a looming mismatch between the world’s strengthened climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals that are essential to realizing those ambitions. The challenges are not insurmountable, but governments must give clear signals about how they plan to turn their climate pledges into action,” the IEA’s executive director Fatih Birol pointed out.

Conclusion

In fact many countries have signaled their intention to spend hundreds of billions of dollars on transitioning their fossil fuel-run economies to those built on electric vehicles and renewable power.

This is one of the main reasons we at AOTH believe that metal prices will remain elevated for the foreseeable future. If governments decide that they need to spend colossal amounts of money on combating climate change through electrification and decarbonization, there will be a direct demand for more minerals.

China, the world’s biggest commodities consumer, has committed to spending at least US$2.3 trillion this year alone, on thousands of major projects, according to Bloomberg. This is in addition to the $900 billion ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ and ‘Made in China 2025’.

The United States is pursuing its own $1.2 trillion infrastructure package, to be spent on roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, among many other items.

The US, which has long sought to improve its battery supply chain, recently invoked its Cold War powers by including lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite and manganese on the list of items covered by the 1950 Defense Production Act, previously used by President Harry Truman to make steel for the Korean War.

To bolster domestic production of these minerals, US miners can now access $750 million under the act’s Title III fund, to be used for current operations, productivity and safety upgrades, and feasibility studies. The DPA could also cover the recycling of these materials.

Later this year, the Department of Energy will begin doling out over $7 billion in grants for battery production, nearly half of which are earmarked for domestic supplies of materials and battery recycling. The DOE has also committed $45 million in funding for battery development called the Electric Vehicles for American Low-Carbon Living program. It’s all part of the Biden administration’s goal of making half of all new vehicles sold in the United States electric by 2030.

These expenditures are inflationary and in the short term will clash with the current mandate of central banks to crush consumer demand as a way of bringing down unreasonably high inflation. It’s a battle that I believe will be won by government infrastructure spending.

When you think about all that is happening to pressure prices — climate change; resource nationalism; NIMBYism regarding new mines in North America & Europe, lower ore grades and poor metallurgy; decarbonization & electrification, hundreds of new mines required to meet battery metals’ demand; malinvestment in mining and oil and gas; money-printing “out the wazoo” to cover annual deficits and government bond purchases (QE), all the pandemic-related stimulus payments to Americans; and the trillions in promised new spending, that hasn’t yet been factored into inflation — there is no way that the Fed is going to have an impact on inflation. How can it?

On the other hand, without a major push by producers and junior miners to find and develop new mineral deposits, glaring supply deficits are going to beset the industry for some time.

Either way, we are looking at elevated prices for critical metals and certain industrial metals that are central to the new green economy, like copper and aluminum, for years if not decades to come.

That’s great news for the future, but what about now? Lately there have been a lot of negative headlines about a coming recession. Resource investors who run with the herd may choose to take their profits, if any, and exit the market.

The fearful will stay in cash, while the hopeful will look for opportunities. We think we just presented one with G&R’s Commodity Prices/ Dow Jones Industrial Average chart. It shows that there hasn’t been a better setup for commodities than now, over a time frame spanning 120 years.

I’m taking advantage of what I think I know, getting Ahead of the Herd, by buying private placements, and shares in the open market of my favorite junior resource companies.

After all who owns the world’s future mines?

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.