The commodities bull market is just getting started

2022.06.23

Inflation is at a 40-year high, making commodities, which protect investments from rising prices and currency debasement, a good place to park your hard-earned cash.

Some investors like to play commodities by purchasing an exchange-traded fund (ETF), but we prefer to go straight into the metals we are most bullish on. Buying shares in a producer is another common strategy, however history shows that junior explorers offer better leverage to rising metals prices. And they happen to be cheap. For the most part, companies exploring for copper, graphite, zinc, nickel, lithium, silver and cobalt, have not matched soaring commodity prices.

There are many reasons to be bullish on commodities and, a lot to indicate that inflation is not going away anytime soon, thus setting up the conditions for a multi-year commodities up-trend.

First, there has been a lack of spending on exploration and development, leading to current and looming supply shortages for a number of metals. The mining companies in the mid-2010s basically ate each other and by shutting down exploration there was no accretive increase in reserves. Lower ore grades have also become an issue.

Second, natural resources are being used up faster than they can be replenished; this is another theme driving commodity prices higher.

Third, countries that have the metals needed to fuel economic growth are guarding them more closely than previously; resource nationalism is on the rise.

For example Chile and Peru, the number one and two copper producers, are both seeking to raise the royalty tax on copper miners, while in the DRC, Africa’s top copper-mining country, the government banned the export of copper and cobalt concentrates — an action almost identical to what happened in Indonesia with nickel.

Fourth, the United States, China and the European Union need to invest heavily in infrastructure and mining, especially critical minerals needed for the shift toward electrification and decarbonization.

The sum total could be the greatest opportunity to invest in resource stocks in our lifetime. Below we lay out the case for commodities.

Anatomy of a commodities bull

The Bloomberg Spot Index (BCOMSP), which tracks 23 energy, metals and crop futures and is considered a good barometer of the sector, has risen by 31% over the past 12 months! No other traditional asset class comes close to matching this kind of return.

The good news is the party has only just gotten started for investors. In 2022, commodities have been going bonkers as inflationary pressures continue to pile up, with little to no signs of easing. The BCOMSP is up 19%, 6.5 months into the year.

Among the metals that have done extremely well, driven higher by tight markets, are nickel, aluminum and zinc.

Both main oil indices, Brent crude and West Texas Intermediate (WTI), continue to trade above $100 a barrel, supported by supply tightness owing to the war in Ukraine, and OPEC’s failure to increase production, at a time when demand has been recovering from the covid-19 slump.

The jump in oil prices, naturally, has been reflected in more expensive gasoline. In the United States, the price per gallon hit a record $5 a gallon at the end of May; in California, it’s above $6. Canadian pump prices are well over $2 a liter.

A commodities “super-cycle” can happen in the late stages of an economic expansion, when growth is so strong, companies can’t produce enough commodities to keep up with demand. This is the situation the world economy finds itself in as it recovers from the pandemic, which slammed the brakes on global growth in the spring of 2020. By first halting and then restarting supply chains, supply and demand fundamentals for raw materials were thrown out of whack.

According to Bloomberg, investors are putting more money into commodity funds than at any time in the last decade, seeking protection against 40-year high inflation which in the US is running at 8.6%.

Citigroup estimates retail and institutional money in the sector at close to $700 billion, the most since at least 2007, with broad-based commodity exchange-traded funds now holding more than $21 billion, also the most since 2007.

The last super-cycle was 2003-11. From the bottom in 2003 to the peak in 2008, commodities rose over 300%.

The commodities super-cycle of the 2000s collapsed in the Great Recession of 2008, then resumed from 2009 to 2011. It ended in the bear market of 2011-15.

Many are pointing to the formation of a new super-cycle, driven not by fossil fuels and the rise of China, but by “green” metals needed for technologies that mitigate the effects of climate change. This includes the electrification of the global transportation system and the decarbonization of fossil-fueled energy sources (coal, oil, natural gas) as the world’s energy matrix runs more on renewables, chiefly wind, solar and hydroelectric power.

This super-cycle will be completely different from the last one.

The main difference is that 2003-11 was all about feeding China’s insatiable thirst for energy and commodities. The country needed copious amounts of coal and iron ore to make steel, the foundation of its modern economy, as well as copper for construction, telecommunications and transportation. Many more metals including zinc, lead, nickel and tin, were part of the mix. The whole enterprise was fueled by oil and gas, for which China was basically a bottomless pit.

Today it’s not only China that needs a multitude of metals. Many countries have infrastructure deficits they need to try and reduce, along with the global threat of climate change, the evidence for which is growing stronger each year, and is driving economies to rapidly shift away from carbon-emitting energy sources to low-carbon or carbon-free alternatives.

Population growth, which infers a greater need for food and manufactured goods, is another important demand driver.

On top of surging demand for minerals needed to feed new solar and wind power installations, lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and grid-scale utility storage, and traditional “blacktop” infrastructure programs (e.g. roads & bridges), we have current and emerging structural deficits for several metals, that will keep prices buoyant for the foreseeable future.

Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research for Goldman Sachs, says the fundamental setup in the commodities complex, including oil and metals, “remains incredibly bullish”.

Currie gives two reasons for this. First is the fact that global oil inventories are below their five-year moving average, putting upward pressure on prices. According to the IEA, the amount of oil in storage is 1.2 billion barrels lower than in June, 2020. Despite the release of 24.7 million barrels of government stocks in March, OECD industry stocks remain 299 mb below the five-year average.

Second, investing in the oil & gas industry has gone out of favor, with ESG headwinds posing a significant challenge for a sector that badly needs new investments, for production to keep up with demand. Under-investment in new mines and new oil discoveries has resulted in a severe supply-demand imbalance in a number of areas.

Saudi Arabia has warned that, without re-investing in the oil industry to find more deposits, the world could be short 30 million barrels a day in eight years, representing about a third of global supply.

In the current under-supplied environment, high oil and natural gas prices will be with us for the foreseeable future. Read more

Other commentators back Currie’s position.

In a recent article, commodity analysts Goehring and Rozencwajg (G&R) say they are often asked, regarding the commodity bull market, “Have I missed it? Is it too late to make an investment in natural resources?” Their reply is invariably, “Not only is the commodity bull market not over, it has hardly begun.”

(Leigh Goehring and Adam Rozencwajg manage the Goehring & Rozencwajg Resources Fund)

Their conclusion is based on the fact that commodities are currently valued below financial assets, but they will shift to being overvalued, relative to financials, sometime in the next decade, meaning there is still a lot of upside to the sector.

If history is any guide, the pendulum has to swing.

G&R presents a chart showing over the last 130 years, there have been four times when commodities became very undervalued compared to the stock market, measured by the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

These four periods, corresponding to the lowest points on the green line, were 1929, the late 1960s, the late 1990s, and today. The key message is that after each stint of undervaluation, commodities entered large bull markets, before becoming overvalued.

Investors who were smart (and brave) enough to invest during undervalued periods saw huge gains, even in the 1930s. For example, investing in a natural resource portfolio (25% metals and mining, 25% precious metals, 25% agriculture, 25% energy) in 1929 would have returned 122% by 1940, clobbering the stock market, which fell 50% during this time.

As for today’s relevance, an identically composed resource portfolio invested on January 1, 2021, has returned 70% to date, compared to the S&P 500’s 14% gain over the same period.

Despite each of the past three commodity buying opportunities being quite different — the 1930s saw deflation and depression versus the 1970s which experienced high inflation/ currency debasement, and the 2000s which had a bit of everything including a stock market collapse, a global financial crisis and oil prices not seen since the ‘70s — they each had the following in common, besides cheap commodity prices:

- a decades-long commodity bear market that impaired capital spending among extractive industries;

- each period saw excessive money-printing;

- all three periods saw intensive financial speculation; and

- each period saw a major shift in global monetary regimes.

According to G&R,

Commodity prices remain radically undervalued relative to financial assets, and we have great confidence that we will swing from commodities being radically undervalued to commodities being radically overvalued relative to financial assets at some point in this decade. What will that radically overvalued level be? If the stock market stays at present levels, commodity prices would have to surge 600% to become overvalued relative to the stock market. If the stock market falls 50%, commodity prices would still have to rise 250% for our chart to enter “radically overvalued” territory.

The Wall Street firm warns that the biggest risk for investors is selling commodities too soon. For example an investor who liquidated her resource portfolio in 1970 after it advanced 40% would have missed 90% of the rally. In 1999 commodities gained 40% compared to the market which fell 4%. Over the next decade, commodities rallied 150% and resource stocks jumped 325%. If you’d sold in 2000 after commodities advanced 40%, you would’ve missed 95% of the rally. G&R concludes:

As you can see, commodities still have to surge multiple times in price from here before they become overvalued. Given the huge amount of monetary creation that has taken place over the last 14 years and, given that inflation psychology is about to grip both consumers and investors alike, we have great confidence that we are about to transverse from one side of this chart to the other. The great commodity bull market has only started, and investors should us use any resource market pullback as an opportunity to increase their exposure.

Goehring and Rozencwajg Q&A

In a follow-up interview with The Market, Leigh Goehring and Adam Rozencwajg discuss why they expect commodity prices to keep climbing, and how investors can best gain exposure to energy, metals and crops in today’s inflationary environment. The following points, edited for space and brevity, have been re-produced from the Germany-based blog:

The Market: Mr. Goehring, Mr. Rozencwajg, investments in the commodities sector are performing well in the current market environment. What are the prospects for the future?

Goehring: “This will be the decade of shortages. For over thirteen years, huge amounts of the global economy have been starved of capital. Obviously, this trend was showing up first in the global oil and gas industry which is hugely capital intensive.

“It was this erroneous belief that demand for oil and gas on a global basis would have entered into a steep decline by now. There was this view that 2019 was going to be the peak in global energy consumption, and fossil fuels were all going to be replaced by solar farms and wind farms. I make the case that we are further away from that than we have ever been. In many commodity markets, the underlying fundamentals are so strong that demand has confounded time and time again to the upside. And, because we cut back investments, we can’t satisfy that demand. That’s where we are today, and that’s what’s producing the shortages. They are showing up everywhere: There is a shortage of refining capacity, a shortage of coins in the US, a shortage of baby food. These types of shortages are going to pop up here and there. It’s going to be one of the great themes of this decade.”

The Market: What does this mean for investors?

Rozencwajg: “Today’s inflationary pressures are neither transitory nor moderate. Given the significant amount of money printed and the huge amount of debt accumulated throughout the world, we believe Inflation will intensify as we progress through the decade. The surge in commodity prices is basically causing the first stage in this inflationary cycle.

“Interestingly, there are a lot of parallels between 1969 and 2020: There were huge amounts of deficit spending in the years leading up to it, we had a mania in investing in things like conglomerates and the Nifty-Fifty stocks. Just like today, money had been taken out of the extractive industries because they were thought to be an old economy and not needed anymore. Of course, nothing could have been further from the truth.All the different commodity prices, whether we talk about gold, base metals, agricultural commodities or energy, had one of their best ten-year runs as far as data goes back. On the other side, the stock market was up 10% or 15%, but in real terms down substantially. One of the few places to hide was in commodities and natural resources equities.”

The Market: Whether it’s oil, natural gas, copper, uranium or grain: prices have already risen sharply in many areas. Is it even still worth getting in now?

Rozencwajg: “We would argue that this rally hasn’t even started yet. For instance, the energy sector is still less than 4% of the S&P 500 versus 10% on average, and 30% as a high. So what’s going to change that? What’s going to make capital move and ultimately rush into the commodity space? We think an understanding that the era of the last forty years in terms of falling interest rates, low inflation, and rising stock and bond prices together, might be over, and that we are going to have to deal with persistent inflation.”

The Market: Fears are growing that the global economy is cooling down which could weaken demand for raw materials.

Goehring: “I would say this is going to be short-term. Demand for commodities just surprised everyone tremendously over the last four to five years, and there is a specific reason why demand is coming in much stronger than most experts thought. Those forces are still massively at work. They are going to be at work for the entirety of this decade — and almost no one has it in their models.”

The Market: What kind of forces do you mean?

Goehring: “It’s the phenomenon that happens when a country goes through this notch from being poor, measured as $2,000 per capita GDP, to becoming a middle-income country, measured as $10,000 to $15,000 per capita GDP. In the post-World War II period from the early 1950s all the way to 2000, there were approximately 500 to 700 million people globally in that notch. When China entered that notch in 2000, it all of a sudden jumped to almost 2 billion people. Since then, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand have joined that notch phase. That’s another 600 million people. The huge wild card no one is focusing on is India.India has now reached exactly that stage where China was in the year 2000. And it’s beginning to exhibit the same characteristics that China did, especially in oil and natural gas consumption. And then, you also have Bangladesh and Pakistan. So in total, there are another 2 billion people potentially in this notch period.

“When countries progress to becoming a middle-income economy, their consumption preferences change. In oil for example, in a country with a $2,000 per capita GDP, people ride around on bicycles mostly. Then, when they get to $4,000 to $5,000, they buy a moped. Next comes a motorcycle, and when they get to $10,000, they buy a Toyota. Obviously, the poster child for this phenomenon is China, but it’s going on in huge parts of the emerging market world right now.”

The Market: Why has the demand for natural gas increased so much?

Goehring: When you’re poor, you burn a lot of coal because it’s cheap: It’s easy to transport, it doesn’t require any storage since you just throw it onto the ground, and you can provide a lot of electricity. However, there are a lot of externalities with coal, a lot of pollution. As you get richer, you don’t want to live in a degraded environment. Hence, as a society you begin to change your entire energy consumption mix. For instance, in electricity generation you switch over from burning coal to burning natural gas. And, this phenomenon not only exists in energy markets.

The Market: In which areas is this phenomenon also taking place?

Rozencwajg: “Copper has the same demand characteristics. As a country gets richer, it needs more copper in its installed base, and this is a reason why copper continues to be our favorite metal. Copper demand remains very strong, and mine problems have become a critical issue. That’s why we remain extremely bullish and believe copper prices are heading much higher. Accordingly, investors should maintain significant exposure to copper related equities. Another example is agriculture. That’s another area in a full-blown crisis right now.

“As countries get wealthier, everybody wants to change their diet: less rice and bread, more animal protein. That requires a lot more grain.Obviously, all those countries in Southeast Asia are going through that increase in protein consumption phase right now, creating very strong demand. On the supply side, surging natural gas and coal prices severely disrupted nitrogen and phosphate fertilizer production, primarily in Europe and China. As a result, global agricultural markets are being buffeted by several almost unprecedented forces.”

The Market: The recent surge in energy prices was triggered by the Russian attack on Ukraine. But now the US and other OECD countries are taking countermeasures by releasing strategic oil reserves. How will that affect prices?

Rozencwajg: “While Russia’s invasion has made the energy shortage much worse in the short term, the underlying problems have been building for many yearsand cannot be easily remedied. In previous cycles, oil prices would have crashed in the light of such an announcement. This time, the release of strategic reserves has hardly dented the oil price.”

Goehring: “As we progress through 2022, global oil markets are going to face a situation in which we never ever have been before: By the fourth quarter, global oil demand could very well bump up against total world pumping capability. We have never been even close to that, and we don’t even know what that world looks like.”

Rozencwajg: “In a normal cycle, falling inventory levels, rising prices, and improved profitability would have attracted capital back into the industry by now. Instead, ESG commitments made over the past several years are keeping capital from reentering the oil and gas industry, making the production problems much worse. E&P capital spending is still down 50% from the peak with shale spending down 60%. This is incredibly important given the US shale basins represented nearly 90% of all non-OPEC+ growth in the previous decade.”

The Market: Unlike other commodities, precious metals have barely moved so far this year. What is your investment case for gold?

Rozencwajg: We talked about how this is going to be the decade of shortages, and as a result this is going to be the decade of inflation.In a world where people begin to lose faith in the value of currencies because of excess money creation, gold is going to come back in favor.”

Commodities demand surge

The new commodities super-cycle being touted by Goldman Sachs, G&R and others, is tied to the infrastructure deficits that many countries need to reduce. Basic infrastructure such as roads, bridges, water & sewer systems, has been poorly maintained, and requires hefty investments, measured in trillions of dollars, to repair or replace.

China, the world’s biggest commodities consumer, has committed to spending at least 14.8 trillion yuan (US$2.3 trillion) this year alone, on thousands of “major projects”, according to Bloomberg. They are part of Beijing’s most recent Five-Year Plan that calls for developing “core technologies” including high-speed rail, power infrastructure and new energy.

The United States is pursuing its own trillion-dollar infrastructure package, to be spent on roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, among many other items.

For such plans to work, extensive minerals are needed to build the required infrastructure, and will have to compete with one another (plus every other country) to do so, driving commodity prices higher.

It’s no wonder that analysts now are so bullish on commodities.

An extension of the infrastructure buildout is the global transition towards a “green economy”, which can only be accomplished with renewable power, electric vehicles and energy storage technologies.

All of these require lots of minerals. The amount of raw materials we’ll need to extract from the Earth to feed this transition is staggering.

According to BloombergNEF, it would take 10,252 tons of aluminum, 3,380 tons of polysilicon and 18.5 tons of silver to manufacture solar panels with 1GW [gigawatt] capacity.

Wind turbines need steel, copper, aluminum, nickel and other materials. To construct wind turbines and infrastructure with the power capacity of one gigawatt, BNEF found that 154,352 tons of steel, 2,866 tons of copper and 387 tons of aluminum are needed.

For lithium-ion batteries, the key metals are copper, aluminum, lithium, nickel, cobalt, and manganese. BNEF estimates that it would take 1,731 tons of copper, 1,202 tons of aluminum, and 729 tons of lithium to manufacture 1GWh batteries.

All in all, BNEF estimates that the global transition will require about $173 trillion in investments over the next three decades; until then, every commodity under the sun will be gobbled up.

In fact, mined and quarried commodities have been used in vast amounts throughout history, and it’s mind-boggling to contemplate how much of these everyday materials we consume.

According to the US Geological Survey, to maintain our standard of living, each person requires over 40,000 pounds of minerals a year, including:

- 10,765 pounds of stone

- 7,254 pounds of sand and gravel

- 685 pounds of cement

- 148 pounds of clays

- 383 pounds of salt

- 275 pounds of iron ore

- 168 pounds of phosphate rock

- 35 pounds of soda ash

- 34 pounds of aluminum

- 12 pounds of copper

- 11 pounds of lead

- 6 pounds of zinc

- 5 pounds of manganese

- 25 pounds of other metals

At today’s level of consumption, the average newborn infant will need a lifetime supply of: 871 pounds of lead, 502 pounds of zinc, 950 pounds of copper, 2,692 pounds of aluminum, 21,645 pounds of iron ore, 11,614 pounds of clays, 30,091 pounds of salt, and 1,420,000 pounds of stone, sand gravel, and cement.

Taking a closer look at copper, nickel and aluminum, the USGS notes that roughly 700 million tonnes of copper have been produced to date, an amount that would fit into a massive red-metal cube measuring 430 meters a side.

When the tonnage of discovered copper is added to identified copper deposits, the total is 2.8 billion tonnes, fitting into a cube 680 meters per side. There are an estimated 6.3 billion tonnes of copper on Earth. Of the identified copper still sitting in the ground, nearly two-thirds (65%) is in just five countries: Chile, Peru, Mexico, Australia and the US.

Nickel is one of the most in-demand metals for the future green economy, implying a much higher consumption level. Yet nickel usage has been steadily climbing over the past 30 years. Are there enough nickel deposits to go round? And remember only batteries that use nickel sulphide are green…

According to the International Nickel Study Group (INSG), world nickel demand doubled from 1.123 million tonnes in 2000, to 1.465Mt in 2010, and has averaged 3.8% growth per year since then. Asia is by far the largest market for nickel, representing about 82% of world demand, with China accounting for close to 60% of total demand.

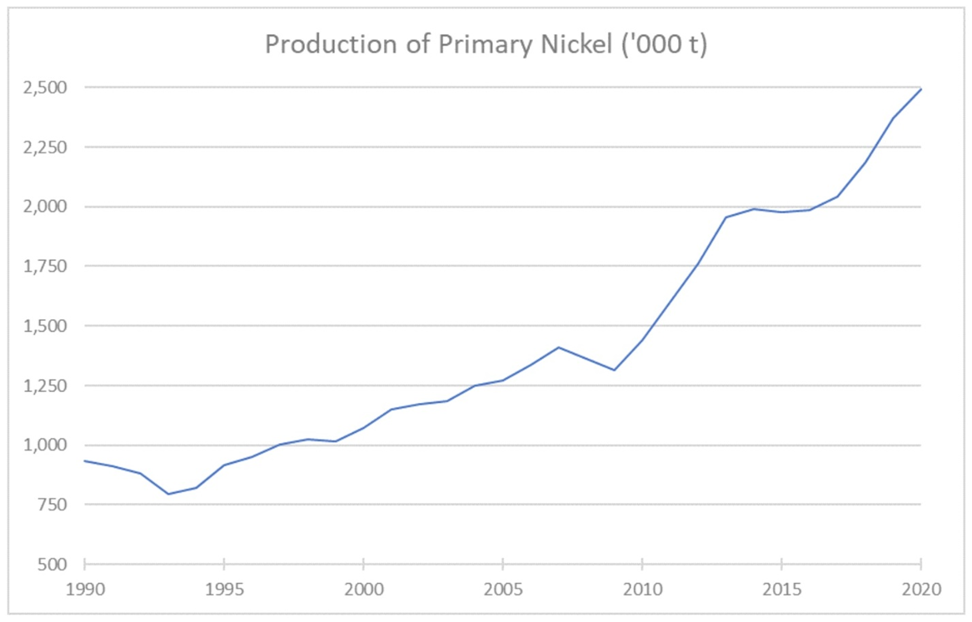

Nickel production has also increased steadily over the years. Strong global growth supported rising output of primary nickel until 2007. The adoption of nickel pig iron (NPI), which started being produced in China in 2005, created a new use for raw nickel. NPI production has more than tripled between 2010 and 2020, reaching about 605,000 tonnes that year, with practically all of NPI used in China and Indonesia for the production of stainless steel. The total market for nickel was 2.5Mt in 2020, with production growth averaging 3% during the 2000s, and between 3 and 5.6% in the following decade.

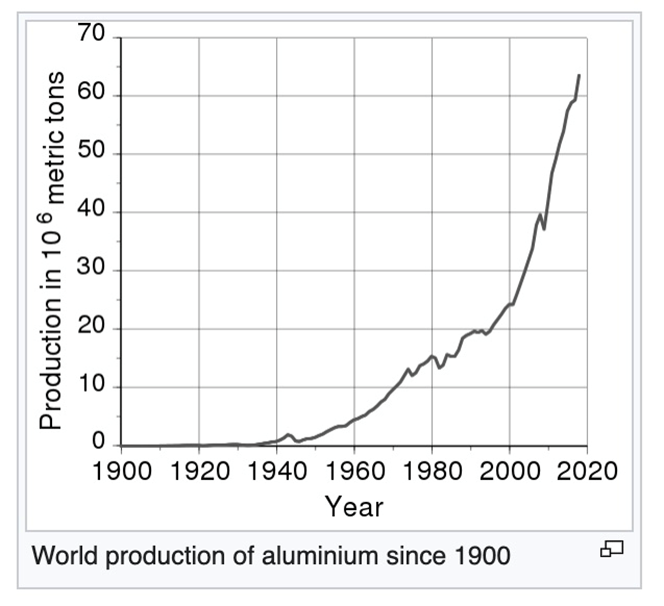

From 1945, aluminum consumption grew almost 10% for nearly three decades, with the lightweight metals finding a need in building applications, electric cables, foil and airplanes. A major boost came in the 1970s with the manufacture of aluminum cans. The increased demand for aluminum end-product, made from the mineral bauxite, put aluminum on the London Metal Exchange in 1978.

The United States, the Soviet Union and Japan produced the lion’s share of aluminum in 1972. This changed in the 2000s, with the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) growing their combined share of production from 32.6% to 56.5%, while their share of consumption more than doubled from 21.4% to 47.8%.

Let us now put the supply shortages that are integral to the new commodity super-cycle, under the microscope.

Running short

Most natural resource modeling has greatly overstated the amount of fossil fuels and minerals the petroleum and mining industries will be able to extract. Forecasters assume that as long as we have the technological capability, and resources are still in the ground, extraction will follow.

In fact this model greatly overstates the quantity of future resources that can actually be mined. The reason is because the world economy tends to run short of many types of resources simultaneously.

But that doesn’t mean producers will automatically go after these commodities. For several minerals, including copper, grades are declining, meaning more ore has to be mined for the deposit to be economic. More complicated mineralogy often means more complicated, and more expensive, metallurgy.

A report last year by Goehring & Rozencwajg Associates (G&R) found that both greenfield and brownfield copper reserve additions are expected to disappoint through the decade.

According to the New York-based research firm, the number of new world-class discoveries coming online this decade “will decline substantially and depletion problems at existing mines will accelerate.”

Additionally, geological constraints surrounding copper porphyry deposits, a subject few industry analysts let alone investors understand, will contribute to the problems, the report said.

G&R also pointed out that miners have been “artificially” boosting reserves by lowering their cut-off grades when copper prices rise in order to make more profit. But this practice only works to a certain point, when cut-off grades cannot be reduced any further.

By 2015, the industry’s head grade was already 30% lower than in 2001, and the capital cost per tonne of annual production had surged four-fold during that time — both classic signs of depletion.

According to the G&R model, the industry is “approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades,” and brownfield expansions are no longer a viable solution.

“If this is correct, then we are rapidly approaching the point where reserves cannot be grown at all,” the report concluded. This highlights the importance of making new discoveries in establishing a sustainable copper supply chain.

Over the past 10 years, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically, with tonnage from new discoveries falling by 80% since 2010.

Referring again to the Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index, which hit a record earlier this year, driven in part by surging oil prices, Goldman Sach’s Jeff Currie said he’s never seen commodity markets pricing in the shortages they are right now.

“I’ve been doing this 30 years and I’ve never seen markets like this,” the commodity expert said in a Bloomberg TV interview. “This is a molecule crisis. We’re out of everything, I don’t care if it’s oil, gas, coal, copper, aluminum, you name it we’re out of it.”

Lingering supply chain issues from covid and the war in Ukraine have made these pressures even stronger.

Nickel prices spiked following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, a major supplier of the base metal through state-owned miner Norilsk.

Copper is seeing its cupboard dry up, from a dearth of new discoveries and lack of capital spending on mine development in recent years.

Analytics firm S&P Global predicts that due to a shortage of projects, copper supply will lag demand as soon as 2025.

In 20 years, BloombergNEF says copper miners need to double the amount of global copper production, just to meet the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles — from the current 20Mt a year to 40Mt.

Remember, copper is already one of the most consumed industrial metals on the planet, and the bellwether for the global economy. The commodity will always be in great demand, and the threat of a decades-long supply shortage should keep its price elevated.

Another commodity in the spotlight is lithium, the key ingredient in electric vehicle batteries.

S&P Global forecasts that this year, further demand growth could push the lithium market towards a deficit as increased use of the material outstrips production and depletes stockpiles.

Supply of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) is forecast to jump to 636,000 tonnes in 2022, up from an estimated 497,000 in 2021 — but demand will move even higher to 641,000 tonnes, from an estimated 504,000, S&P said in its December 2021 report.

Metals such as nickel, cobalt, graphite and zinc, are also surging, on supply concerns.

Zinc reportedly moved from a 5.3 million tonne surplus in 2020 to a million-tonne deficit in 2021, with warehoused metal in London and Shanghai recently plummeting to six days consumption.

The fourth most used metal in the world is likely to stay at multi-year highs in 2022 owing to high energy costs resulting from the war in Ukraine. Spot zinc is up 28% over the past year, and Fitch Solutions has raised its 2022 price target to $3,500 a tonne from $2,900/t. At this rate, zinc is on track to reaching its all-time high of $2.06/lb, in November 2006.

Nickel has done even better, tracking 48% higher over the past 12 months, helped by an early March record-setting spike, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Although the base metal used in stainless steel and EV batteries has since retreated as a result of (temporary) Chinese covid lockdowns and reduced demand, Fitch Solutions expects new stimulus measures announced by the Chinese government on May 31, and lower Russian supply, will drive prices higher than current levels in Q3 2022.

Echoing what Goldman’s Jeff Currie and others are saying about a new commodity supercycle focused on the green economy, Eurasian Resources’ CEO Benedikt Sobotka believes that commodities right now are in a “perfect storm”.

Sobotka told Reuters the fossil fuel resurgence is temporary and the transition to a lower-carbon can’t be stopped. Meeting the demand for clean energy and transportation will require an eye-watering $50 trillion over the next three decades, or an investment of $200-300 billion per year. He predicts the majority of funds will go into the mining of copper, nickel, cobalt and other “green” metals, and forecasts a 20% rise in copper prices by the end of this year.

In the same way that the oil and gas industry has been starved of investment dollars, in favor of trendy renewable power projects, Sobotka notes that “Years of under-investment in mining of metals essential to energy transition, supply shocks and high energy prices will continue to drive commodity prices higher.”

Resource nationalism

Widespread metal supply shortages are being made worse by resource nationalism — the tendency of governments to localize the mining industry and to increase the extraction costs to foreign miners.

With much of the “low-hanging fruit” already picked, there is a need to go further afield and dig deeper to find metals at the grades needed to mine them economically. This usually means riskier jurisdictions that are often ruled by shaky governments, with an itchy trigger finger on the resource nationalism button. Recent examples include Chile, Peru, Indonesia, the DRC, and even the United States.

Conclusion

For the first time in history, there is a confluence of demand drivers that threaten to outstrip supply, potentially depriving the United States (and Canada) of the minerals they need to drive the economy in the directions they want it to go.

Not only are metals required for electrification and decarbonization, the so-called green shift, they are also needed to replace traditional infrastructure (think roads, bridges, public buildings), to harden targets vulnerable to climate change (e.g. levies, storm breaks) and to relocate infrastructure and populations in the way of storm surges and sea rise.

As we know, the cycle in the 2000s revolved around China and its steady demand for oil, gas, coal and metals.

This cycle is different because its causes boil down to a number of factors, including the demand for many raw materials outstripping supply; the heavy demand for commodities envisioned by infrastructure renewal, electrification and decarbonization; climate change; pollution abatement; and population growth. Notice we haven’t even talked about the immediate supply pressures resulting from pandemic recovery, that have resulted in multi-year highs for metals such as nickel, aluminum, copper and lithium, and record-setting natural gas prices particularly in Europe.

The question is, is there a way that the system can ramp up now, to the levels of production needed to satisfy demand, for all of the above-mentioned areas, all at the same time?

The answer is no.

Even if the investments in mining/ oil and gas that have been lacking were suddenly returned to the sector, there remains the problem of most accessible deposits having been mined out, the so-called “low-hanging fruit”. Now companies are having to go deeper underground, or farther afield, to find minerals at the scale and grades needed for extraction. Their remote locations will require huge investments in infrastructure, and those with complicated mineralogy will face higher processing costs. You still have countries wanting to protect their minerals from foreign mining companies, tax them more, or enact other forms of resource nationalism. It will still take 20 years to develop a mine in North America. The trend is for more ESG, more consultations with focus groups, meaning a lot more talk and a lot less action when it comes to regulations and permitting.

Ironically, all of these deterrents to mining are there, and growing, at precisely the same time that demand for metals is rapidly accelerating.

The commodities bull market is only just beginning.

Commodities are currently valued below financial assets, but they will shift to being overvalued, relative to financials, sometime in the next decade, meaning there is still a lot of upside to the sector.

At present levels, commodity prices would have to surge 600% to become overvalued relative to the stock market. If the stock market falls 50%, commodity prices would still have to rise 250% for G&R’s chart to enter “radically overvalued” territory.

Indeed G&R says the biggest risk for investors is selling commodities too soon – if you’ve got them, you’d best hold onto them, because they’re going up.

What’s it going to take to cause commodities to shift from grossly undervalued currently, to overvalued and time to sell? G&R says “it’s an understanding that the era of the last 40 years in terms of falling interest rates, low inflation, and rising stock and bond prices together, might be over, and that we are going to have to deal with persistent inflation.”

I would agree. Though some see the global economy cooling down and weakening demand for raw materials, this is temporary. For example, China has lifted the covid restrictions that have been suppressing demand for a lot of commodities, and the country has earmarked $2T in infrastructure investments for 2022 alone, requiring mega metals.

Arguably, the forces keeping the fires burning under commodity prices, will continue to be at work for the rest of this decade, if not longer.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.