Zinc cupboard nearly bare as price soars

2019.03.26

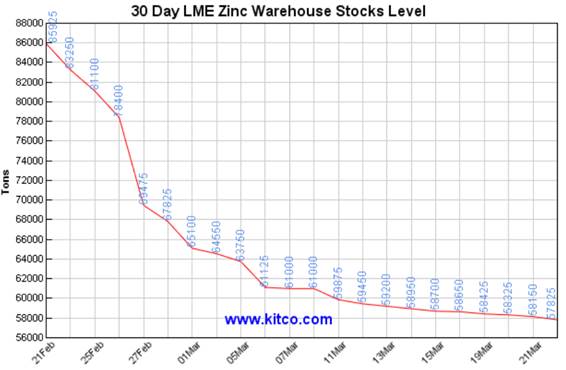

Zinc inventories have fallen to the point where there is less than two days worth of global consumption locked in London Metal Exchange (LME) warehouses. The paucity of the metal used to prevent rusting caused prices to spike to the highest they’ve been since last June.

Monday morning zinc prices were US$2,845 a tonne or $1.29 a pound, after data showed LME warehouses hold just over 58,000 tonnes. For perspective, the all-time high for zinc was $2.07/lb in 2006, compared to historic lows below 40 cents back in the early 2000s.

In 2017 zinc enjoyed a spectacular run from $1.19 a pound to $1.61 within only six months (+35%). Prices got a nice uplift from mine closures and an expected long-term structural supply deficit. The metal’s hot hand had many juniors roaming around with boots on the ground trying to find the next zinc deposit.

History may be repeating itself, as the undersupply narrative continues. While zinc stocks peaked at the height of the commodities boom in 2012, they just keep dropping. The last time the zinc cupboard was this bare, the world economy was mired in the Great Recession.

In this article we take a deep dive into zinc, a fascinating yet underappreciated metal whose history pre-dates the Romans.

History

These days it’s hard to imagine life without zinc, which is primarily used as an anti-corrosion agent for steel. In the ancient world, though, zinc was relatively rare, and expensive.

The oldest zinc production can be traced to the Zawar mines of Rajasthan, India, in the 6th century BC. An estimated million tonnes of zinc metal and zinc oxide was produced from Zawarbetween the 12th to 16th centuries.

Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, was used throughout the ancient Middle East, Greece and India, around the 2nd and 3rd century. Brass objects have been recovered from Assyria from 3,000 BC and Palestine from between 1,400 and 1,000 BC.

The famous traveler Marco Polo reported the production of zinc oxide from Persia, where a solution of zinc vitriol was used to treat eye inflammation.

It was initially produced from carbonate of zinc – a zinc salt used for medical purposes. The ancient Greeks knew about zinc, with ornaments made of 80-90% zinc and lead, iron and antimony found to be 2,500 years old. The Romans made calamine brass by heating powdered calamine – a zinc-containing mineral – mixed with charcoal and copper that was cast into weapons or coins.

Pure zinc (an element that can’t be broken down further) wasn’t made until the 1,200s in India. Alchemists heated zinc ore with with charcoal in a covered crucible, which produced a vapor. When the vapor cooled, it was collected in a condenser using tufts of wool. For this reason it was called lana philosophica, which is Latin for “philosopher’s wool”.

Until the 18th century, zinc was imported from India and it was very costly.

Properties

The bluish-white metal with a dull finish is hard, brittle, and a good conductor of electricity. Its chemical symbol is Zn and its atomic number is 30. Zinc is chemically close to magnesium (Mg), which has similar-sized ions. It has relatively low melting and boiling points, at 419.5 degrees C and 907C, respectively.

Zinc is the fourth most common metal in the world, behind iron, aluminum and copper. The base metal is most often alloyed with copper to make brass, but other binary alloy metals include aluminium, antimony, bismuth, gold, iron, lead, mercury, silver, tin, magnesium, cobalt, nickel, tellurium and sodium.

Geology and processing

Zinc comprises 0.0075% of the Earth’s crust, making it the 24th most abundant element. Its most common ore is the sulfide mineral sphalerite. Zinc is almost always found in combination with other base metals such as copper and lead. For that reason, 95% of zinc is mined from sulfide ore deposits where sphalerite is mixed together with copper, lead and iron sulfides. Some of these are volcanogenic massive sulfide (VMS deposits). About 70% of of the world’s zinc comes from mining, the other 30% from recycling. Nearly 90% of zinc is consumed by industry, and half of global demand is from China.

According to the US Geological Survey, in 2018 the top zinc-producing countries were China, Peru, India and Australia. In terms of reserves, Australia has the most zinc at 64 million tonnes, second is China at 41Mt, and Peru is in third place at 28Mt, of the world’s identified zinc resources of 1.9 billion tonnes.

Zinc is refined through a process that includes grinding, flotation and roasting, followed by pyrometallurgy or electrowinning. The ore is first ground to a fine powder, then floated to get a zinc sulfide ore concentrate consisting of about 50% zinc, 32% sulfur, 13% iron and 5% silicon dioxide (quartz). Roasting then converts the concentrate to zinc oxide. Pyrometallurgy using carbon or carbon monoxide reduces the zinc oxide to metal. If electrowinning is the chosen method, the zinc is leached from the concentrate with sulfuric acid, before being fed into an electric arc furnace and recovered from the dust, mostly through the Waelz process.

Uses

While its primary use is to stop steel from rusting, other applications are shoring up demand. Adding zinc to fertilizer increases soil productivity, and there is research being conducted to develop a nickel-zinc battery for use in electric vehicles. Zinc, of course, is already used in alkaline batteries.

Every steel product including buildings and cars, is galvanized with a zinc coating, making it a highly-prized metal.

Zinc is also used heavily in infrastructure build-outs. This includes desperately needed bridges, public buildings, power stations, dams etc. in the US, much of the developing world, and China’s Belt and Road Initiative which along with needing billions of tonnes of copper, is going to require a lot of steel containing zinc.

Zinc alloys including brass are used in corrosion-resistant marine components and musical instruments, to name a couple of more applications.

Any discussion of zinc would be incomplete without a mention of its medical uses. Zinc is an essential mineral for the human body and zinc deficiency is a serious condition, remedied by zinc supplements.

Market

The zinc market was in deficit in 2018. According to the USGS, despite new zinc mines opening in Australia and Cuba in 2017, and increased production at the Antamina mine in Peru, supply failed to keep up with consumption. The International Lead and Zinc Study Group states that global refined zinc production in 2018 was 13.42 million tons versus 13.74 million tons consumed, leaving a deficit of 322,000 tons.

Some very large zinc mines have been depleted and shut down in recent years, with not enough new mine supply to take their place.

MMG’s shuttered Century mine for example used to supply 4% of the world’s zinc. Between the shutdown of the Lisheen mine in Ireland, Century, and Glencore’s Brunswick and Perseverance mines in Canada, over a million tonnes was ripped from global zinc production.

The closed mines represent an estimated 10 to 15% of the zinc market. On the flip side, there have been few discoveries or big zinc projects planned. This is setting the zinc market up for a supply shortage.

The International Lead and Zinc Study Group predicts the zinc market will again be in a deficit position of 72,000 tonnes in 2019.

BMI Research noted in June 2018 that refiners, particularly in China, will have a hard time securing zinc concentrate, due to zinc mine production curtailments in 2015-16 (eg. Rampura Aguchain India, Antamin and Iscaycruz in Peru as well as by Glencore and Nyrstar), along with the aforementioned mine closures. For example tightened environmental standards to deal with choking air pollution meant that Zijin Mining cut 8.2% of its zinc production in 2017.

Chinese smelters rely heavily on imported zinc ore. In 2017 China’s refined zinc production was at its lowest in two years due to problems acquiring zinc concentrate.

The supply squeeze is also trickling down to junior zinc explorers. When zinc prices were low, exploration dried up, meaning there’s not enough new supply to match the growing demand for zinc especially for galvanized steel, Jeff Hussey, president and CEO of Osisko Metals, recently told Kitco News:

“The world needs more zinc mines but we don’t have them because there has been no exploration. If you had all the expected development projects come on line at full capacity, analysts expect that demand will still outstrip supply by mid-2020,” he said. “This means there is a limited risk of further downside in the price long term.”

Wood Mackenzie states that zinc mine closures, attrition and demand growth will require 2.2 million tonnes of new mine capacity a year.

Conclusion

To sum up, more zinc mines are needed to bring supply back into balance with demand, and they will most likely be developed from sulfide deposits. Remember 95% of mined zinc comes from sulfides.

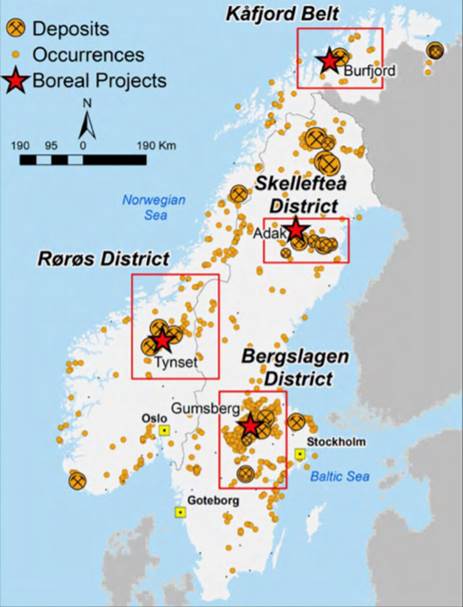

I’ve got my eye on a company with a VMS deposit in Sweden that is getting excellent results from recent drilling. Boreal Metals (TSX-V:BMX) is aiming for discovery success by investigating past-producing mining areas.

Its Gumsberg VMS Project in southern Sweden was mined from the 13th century through to the 1900s, with an astounding 30 historic mines on the property including Östra Silvberg – the largest silver mine in Sweden from 1250 to 1590. Twenty-one holes were drilled between 1939 and 1958.

New geophysical surveys plus reconnaissance drilling and analysis of historical drill data have identified fresh targets near the historical workings.

Check out our video interview with Boreal’s CEO Pat Varas.

For more on Boreal Metals and Gumsberg, read our Boreal Metals hunting high-grade VMS in Sweden.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Boreal Metals (TSX.V:BMX), is an advertiser on Richard’s site aheadoftheherd.com. Richard owns shares of BMX

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.