Wishing you were all mine

2019.09.21

The sun is up

The sky is blue

All I want to say to you

Is that I wish your mine were mine

Nickel prices are holding steady as the top two producers, Indonesia and the Philippines, signal supply disruptions are likely, due to protective mining policies that fit the broad definition of resource nationalism.

As of Friday nickel was trading at US$8.01 a pound, a far cry from a year ago when the base metal was bumping along at between $5 and $6/lb.

Traditionally used as an input for stainless steel, and recently as a battery metal, nickel is up 61% since the start of the year.

Earlier this month prices surged to their highest point in five years (US$17,900) on the London Metal Exchange, after the number one producer, Indonesia, announced it would move an ore export ban forward from 2022, to this January.

The ban is to encourage the building of domestic smelters, and the government is talking tough. It plans to revoke the export permits of companies that fail to meet smelter construction targets.

Added to Indonesia’s pending export ban, good prospects for a demand boost from nickel’s growing use in electric-vehicle batteries, and dwindling global stockpiles, have helped support prices.

Meanwhile the top nickel exporter in the Philippines says it will shutter its operations in Tawa-Tawa, the southern-most province, by the end of this year. The mine, a major supplier to China owned by SR Languyan Mining Corp, is close to being depleted.

The closure is expected to mean a reduction of between 300,000 and 400,000 tonnes of nickel ore destined for China, per month, based on estimates by the country’s Mines and Geosciences Bureau.

Governed under fiery President Rodrigo Duterte, the Philippines has not shied away from interfering in the mining sector, in 2016 launching an industry-wide crackdown on miners as part of a push to clean up the environment. At the time, the closure of over half the island nation’s mines gave nickel prices a dramatic lift.

Resource nationalism

Resource nationalism is the tendency of people and governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over their natural resources. Traditionally, developing countries have seen the benefits of foreign companies coming in to extract their natural resource endowment, in the form of jobs and higher wages for their often-impoverished citizens, and government revenues through taxes, royalties or dividends.

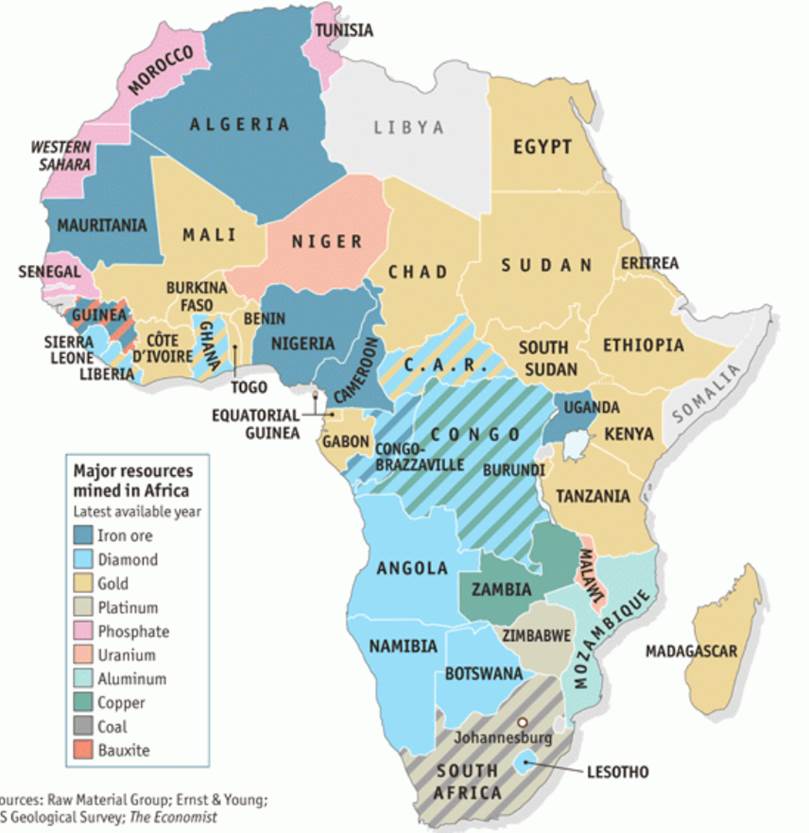

There can also be indirect benefits such as knowledge and technology transfers. Foreign investments often involve infrastructure investments, sometimes on a massive scale, like electricity, water supplies, roads, railways, bridges and ports. The Chinese have used this model very effectively in Africa, where they have set up mining operations but also built schools, roads, water infrastructure, etc.

Still, countries are getting creative in how to bleed away miners’ profits.

Governments have gone beyond taxation in getting more out of the mining sector with a wave of requirements such as mandated beneficiation (where ore is processed locally rather than exported raw), export restrictions (eg. Indonesia) and increased state ownership of mines (eg. Mongolia).

Taking two of these strategies, minerals beneficiated in-country capture more of the value chain, because the finished metal products fetch higher prices. As for governments conflicting with mining companies over the percentages owned, it becomes very difficult for a miner to forecast returns if the host country “moves the goalposts” during a project’s minelife.

Miners are easy targets because mining is a long-term investment and one that is especially capital intensive. Mines are also immobile, so miners are at the mercy of the countries in which they operate. Outright seizure of assets often happens using the twin excuses of historical injustice and contractual misdeeds. There is no compensation offered and no recourse.

Country risk

Part and parcel to resource nationalism is “country risk”.

This is one of the most serious and unpredictable risks facing mining operations and investor interests – where the political and economic stability of the host country is questionable and abrupt changes in the business environment could adversely affect profits or the value of the company’s assets.

We’ve seen many instances of companies losing assets that were lawfully theirs. Several countries come to mind as places where shareholders could, without warning, receive news that their operations have been taken over by the government or its friends, or where permits get delayed or canceled outright.

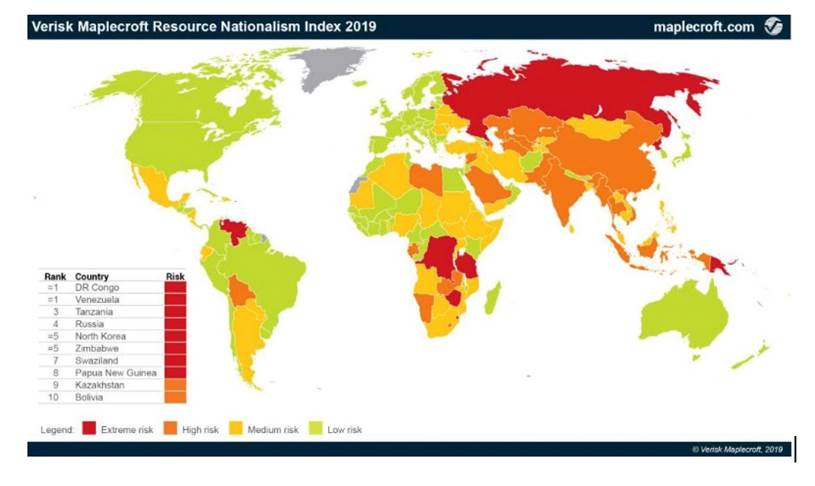

A recent study pointed to 30 countries that have seen a significant increase in resource nationalism risk over the past year. Countries now rated “extreme risk”, according to the March 2019 report by Verisk Maplecroft, include Venezuela and the DRC (both rated highest risk), followed in order by Tanzania, Russia, North Korea and Zimbabwe (tied for fifth), Swaziland and Papua New Guinea.

Security of supply

Resource nationalism is closely tied to security of supply.

For the past 50 years, there has never been a period where demand for natural resources did not increase. Sure, metals prices have fluctuated, but the need for metals has not diminished. In fact, mining is becoming even more important, as the transportation system goes from fossil-fuel-powered to electric, requiring a new mix of metals for batteries and components.

According to a 2019 UN report, over the last five decades, mineral extraction has tripled – and accelerated since 2000 as new economies (ie. China and India, “Chindia”) require huge amounts of materials for building new infrastructure. China is not only the world’s top metals consumer, it is also the leading producer of a number of mined commodities, such as rare earths, gold, antimony, indium, tellurium and tungsten.

Without a way to replace all the resources we consume – harvested food, fertilizers, energy, metals, etc. – we are gradually depleting nature’s bounty, at a rate that is unsustainable, long-term. If we keep going, and economies keep growing, we’re eventually going to run out. The problem is made worse by the global population increasing, along with the continuing wants of people in the developed world (“the West”) and in less-developed countries (who are demanding houses, cars, fridges, cell phones, etc.), putting more pressure on our finite resources.

As competition for scarce resources becomes more intense, access to a secure and sustainable supply of raw materials will become the number one priority for all countries. Increasingly we are going to see countries ensuring their own industries have first rights to internally produced commodities and they will look for such privileged access from other countries, in return.

Threats to access and distribute these commodities include:

- Political instability of supplier countries

- Manipulation of supplies

- Competition over supplies

- Attacks on supply infrastructure

- Accidents and natural disasters

- Climate change

China is a good example of a country that has gone to great lengths to ensure security of supply. Beijing has either purchased overseas mines outright, or more often, bought stakes in them, and signed offtake agreements with suppliers of copper, cobalt, iron ore, and lithium, to name a few of its its key raw materials. The country has locked up the rare earths market through its domination of rare earths mining and processing.

Resource scarcity can also lead to companies going farther afield for minerals than they would in a more abundant market. Gold is a good example. As the number of significant discoveries fall and existing deposits are depleted, gold miners have had to diversify away from traditionally stable countries such as Canada, the US and Australia.

Moving out of these “safe haven” countries, to more risky domains such as Africa and South America, has exposed investors to a lot of additional risk.

Upside = price appreciation

While resource nationalism is among the worst things a mining company can encounter when investing in a foreign country, it can also have a positive impact on metals fundamentals. If enough supply is taken out of the market due to government-imposed restrictions, prices of those metals will rise.

For example Indonesia’s 2014 ban on unprocessed ore exports helped support nickel and bauxite prices, which also tumbled when the ban was relaxed in 2017. In the Philippines, the government of hard-line President Rodrigo Duterte closed 23 mines in 2017, causing the nickel price to climb. Like Indonesia, the southeast Asian nation blocked the export of raw minerals – preferring to process locally – but went further by banning mining in watersheds and forcing companies to seek legislative approval before operating.

More recently, Indonesia and the Philippines have shown that even the threat of mine closures and export bans can have a dramatic effect on a commodity’s price.

Indeed the nickel market is getting tighter and the floor under prices is becoming more solid. As noted at the top, the threat of supply disruptions from the top two producers, Indonesia and the Philippines, has meant a 61% price gain, year to date.

For more on nickel’s extremely positive fundamentals right now, read Dark horse nickel continues to gallop

Other examples

Indonesia isn’t just wrapping the arms of state around its vast nickel reserves. In September 2018 the government, Freeport McMoran and Rio Tinto finally came to an agreement over ownership of Grasberg. The long-running dispute ended with Indonesia gaining a controlling interest in 51% of the world’s second largest copper mine.

Meanwhile another round of resource nationalism is occurring in Africa.

In 2017 Tanzania followed Indonesia’s lead by slapping a ban on the export of unprocessed mineral concentrates and ores. The move reportedly led to Tanzania’s top gold producer, Acacia Mining, scaling back its operations, halving its adjusted earnings (EBITDA) from $82 million to $44 million, on a quarterly basis.

In Zambia, an economic crisis is forcing the country to consider seizing copper mines, according to Bloomberg. The news site reported that the yields on Zambia’s Eurobonds hit record highs (only basket case Venezuela’s yields are higher) after the Zambian government said it plans to seize Vedanta Resources’ assets.

The government wants to liquidate Vedanta’s Konkola Copper Mines (KCM) which it accuses of breaching its operating license and polluting the lands of nearly 2,000 villagers, Reuters said. A court hearing in England is pending.

For its part, Vedanta claims it is owed nearly $180 million in value-added tax refunds.

Zambia, Africa’s second largest copper producer behind the DRC, is expecting copper production this year to be up to 100,000 tonnes less than in 2018.

Zambia’s Chamber of Mines attributes the production drop to changes in mining taxes which have driven up costs and forced copper miners to reduce output. The country’s copper production has already tumbled 11.3% in the first quarter of 2019 versus the last quarter of 2018.

Meanwhile First Quantum Minerals, which is offering to buy the Zambian government’s 20% stake in the country’s largest copper mine, Kansanshi, giving the company 100% control, is also fighting with the government over a $7.9 billion tax bill. The 1.5% increase in mining royalties this year prompted First Quantum to announce plans to fire 2,500 workers, but it later backtracked on the proposal, according to the Financial Post.

Last year the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) raised taxes and royalties on copper and cobalt – of which the DRC is the top producer – amid fierce opposition from miners.

The country’s new mining code “imposed onerous fiscal terms on existing operators and allows heightened levels of government interventionism in the sector. Since June 2018, when the code came into law, the government has attempted to block commercial asset transfers, tried to usurp operators to glean more profit, and choked exports from a cobalt mine,” according to the resource nationalism report cited above.

The legislation takes away a stability clause protecting investments, introduces a 50% windfall profits tax and allows the mines minister to hike taxes on minerals it deems “strategic”. In December 2018, the government declared cobalt strategic, nearly tripling the royalty miners pay on the necessary EV battery ingredient, to 10%.

South Africa’s 2017 amended mining charter, MC III (‘Reviewed Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Charter for the South African mining industry’), introduced a series of “soft” resource nationalism measures that are more social than economic, meant to redress the country’s apartheid past.

MC III increased minimum requirements for Black Person ownership of: prospecting and mining rights; procurement of local good and services; and employment equity (50% at board and executive management level, 60% at senior management, 75% at middle management and 88% at junior management).

Within 24 hours of the new mining charter being published, the South African rand plummeted 2% and mining companies lost ZAR50 billion of market capitalization on the JSE.

Away from Africa, the government of Mongolia is looking to re-write a 2015 agreement it made with Rio Tinto for its huge Oyu Tolgoi copper-gold mine. The mine is currently 34% state-owned, with 66% belonging to a Rio subsidiary, Turquoise Hill Resources. Adding to the confab is Mongolia’s claim that Rio Tinto owes $155 million in taxes.

In Bolivia, President Evo Morales caused widespread consternation in 2006 when he nationalized the country’s oil and gas industry; Bolivia has the second largest natural gas reserves in South America after Venezuela, and an agreement to sell natural gas to Brazil through 2019.

A year after first getting elected, Morales strongly suggested he would nationalize parts of the mining industry. Six years later he confiscated and nationalized a silver and indium mine owned by South American Silver, without paying compensation to its Canadian owners. In 2016 his government announced a crackdown on mining cooperatives after a government official was murdered. The mining sector is dominated by 120,000 miners working in about 1,700 cooperatives.

Major nickel miner Glencore has initiated arbitration proceedings over its investments in two smelters and a tin mine nationalized between 2007 and 2012.

Neighboring Chile has also shown its nationalist colors over threats to its water supply. Fearing a water shortage, the government in 2018 put restrictions on water use in the Salar de Atacama, a dried-up lake bed containing vast lithium reserves.

Albemarle, SQM, Antofagasta and BHP are among the mining companies affected by a ban on new permits to extract water from the southern portion of the salar’s watershed, which supplies BHP’s Escondida, the world’s largest copper mine, and Antofagasta’s Zaldivar Mine. Indigenous populations are also vying for access to water in the parched region.

Chile has also sparred with Albemarle, the world’s largest lithium miner with operations in the Salar de Atacama, for failing to live up to a 2016 contract. The company was supposed to offer a quarter of its annual production at a discount to battery makers – a stipulation put in to help build a mine-to-battery industry in Chile. The country’s nuclear regulator then refused to increase the company’s lithium production quota.

To be fair, first-world countries aren’t immune to resource nationalism. Examples from earlier this decade include the UK government introducing higher resource taxes in the North Sea, Australia increasing mining royalties in Queensland, along with its controversial Minerals Resource Rent Tax (MMRT), and the Canadian government’s recent attempt to stifle resource development through Bill C-69.

Conclusion

Resource nationalism in its many forms appears, at first blush, to be very negative for mineral explorers and producers. Investing in a high-risk country could result in sudden tax hikes, disputes over ownership percentages, a change to the mining code, or in the worst case, confiscation of assets. The outcome is usually more money being shelled out by the mining company, at the expense of profitability and the share price.

And this brief rundown of resource nationalism examples shows there is no shortage; if anything, resource conflicts are increasing. As we deplete the planet of its mineral bounty at alarming speed, countries are going to become more protective of their resources. At the same time, mining companies are being forced to go further afield, to risky countries, to the Arctic, even underseas. As they dig deeper and farther afield, they will find competition for the metals.

On the other hand, resource nationalism can be very helpful to a mineral commodity. Just look at nickel. When Indonesia imposed an export ban in 2014, prices climbed, just as they are now, with the new ban having been brought forward two years. Nickel was also dealt the right cards in 2017 when the Philippines was closing down mines and blocking ore exports. The current market set-up is even better, with the top two producers both looking at bringing less nickel ore to market.

The flip side is what happens when resource nationalism is relaxed. While that is usually good for mining companies, it can be bad for investors, since it often means the removal of an impediment(s) to mining, less money expended, and therefore higher output that can drag down prices.

As resource investors, we always need to be aware of resource nationalism in the countries our companies are doing business with.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.