Why we’re running out of copper – Richard Mills

2026.02.11

LME copper hit an all-time high of 13,300 per tonne ($6.03/lb) on Jan. 6, marking a 50% year-on-year increase.

Along with all the usual applications for copper — in construction, transportation and telecommunications — demand is being driven by ongoing electrification and decarbonization of the transportation system and the exponential growth in battery storage.

Furthermore, copper is vital to artificial intelligence and the infrastructure that supports AI. The associated increase in data centers is causing an explosion in electricity demand, requiring substantial copper for new infrastructure and power transmission.

This all boils down to everything driving the world’s economies needs more copper, in the face of persistent constraints on mine supply.

Supply crunch

While the copper market was roughly balanced in 2025, meaning that refined production met consumption, mine supply was severely disrupted and will likely create a deficit in 2026, states the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS).

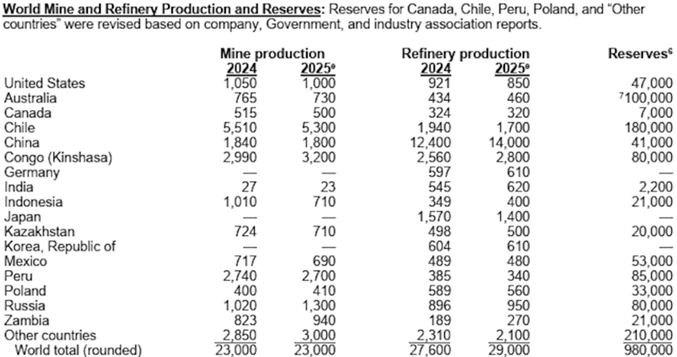

A significant long-term deficit is projected, potentially exceeding 6 million tonnes annually by the early 2030s. Total output from copper mines in 2025 was 23 million tonnes, according to the USGS.

Google AI identified key trends in copper supply in 2026:

- Structural Deficit: The industry is moving into a structural shortage as demand outpaces new mine development.

- Production Constraints: Despite high demand, mine supply growth for 2026 is estimated to be low, at around +1.4% (roughly 500,000 tonnes).

- Record Prices: Concerns over tight supply and strong demand sent spot copper prices to record highs, exceeding $14,000 per tonne at the beginning of 2026.

- Key Producers: Chile (19%), Peru (10%), Australia (10%), Russia (8%), and Congo (8%) hold the largest reserves.

- Shortage Drivers: A projected 50% increase in demand from current levels by 2030, accelerated by energy transition and AI, necessitates an estimated 8Mtpa of new mining capacity by 2035.

- Recycling Impact: Roughly 30% of global copper demand is currently met via recycling, which is crucial for filling the gap.

- Geopolitical Risk: A high concentration of smelting and refining capacity in China (40-50%) poses supply chain risks.

- Operational Disruptions: Significant issues, such as the shutdown of major mines (e.g., Indonesia’s Grasberg) through Q2 2026 are tightening the market.

- Investment Needed: Over $210 billion in capital investment is required by 2035 to meet demand, according to Wood Mackenzie.

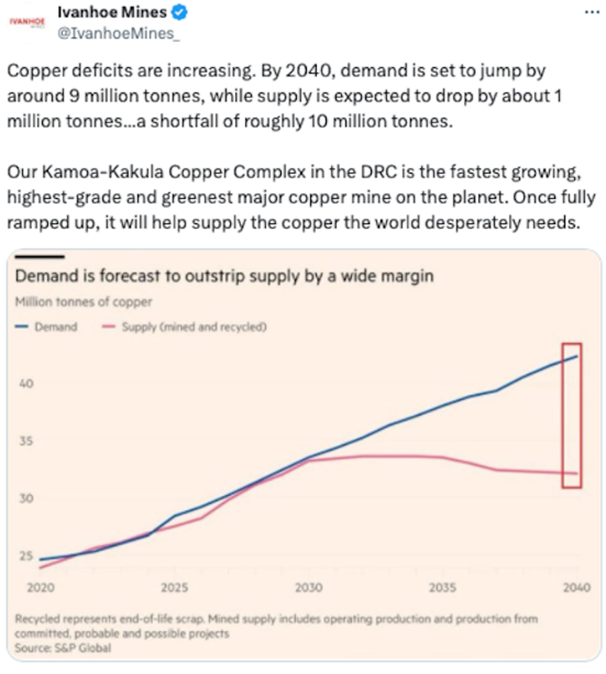

A new study released on Jan. 8 by S&P Global Market Intelligence and S&P Global Energy found that copper supply is expected to fall 10Mt short of demand by 2040, putting at risk industries such as artificial intelligence, defense spending and electrification.

The shortage would be 23.8% shy of the projected demand of 42Mt, even as copper recycling doubles to 10Mt. AOTH research has found that copper supply has not been able to meet demand without recycling for the past several years.

“Here, in short, is the quandary: copper is the great enabler of electrification, but the accelerating pace of electrification is an increasing challenge for copper,” Daniel Yergin, vice chairman at S&P Global, who co-chaired the study, said in a statement. “Economic demand, grid expansion, renewable generation, AI computation, digital industries, electric vehicles and defense are scaling all at once — and supply is not on track to keep pace.”

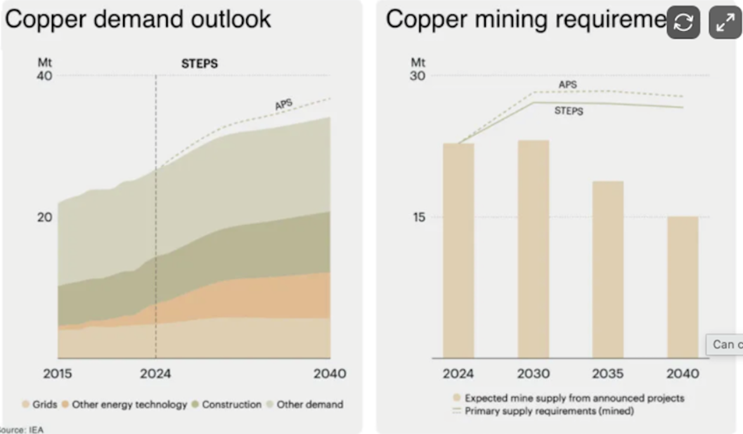

Without significant changes to supply, global copper production is projected to peak at 33Mt in 2030 before declining, while demand is expected to surge 50% from current levels, according to the study.

An additional 10Mt of primary supply will be required by 2040. But without significant investment, primary production could reach just 22Mt, a million tonnes below current levels.

Among the supply constraints identified by the report are declining ore grades, rising energy and labor costs, complex extraction conditions and lengthy permitting times. The average timeline from discovery to production spans 17 years.

Supply chain concentration adds another layer of risk, says S&P Global, with just six countries responsible for around two-thirds of mine production. China is both a miner and a refiner, with the country accounting for approximately 40% of global smelting capacity and 66% of copper concentrate imports. This makes the global supply vulnerable to supply shocks and trade barriers, the report said.

An earlier (November 2025) blog post by Wood Mackenzie brings its forecast five years ahead of S&P Global, with the consultancy expecting global demand for copper to surge 24% and reach 43Mtpa by 2035.

It says four emerging demand disruptors will add 3Mtpa, almost doubling growth from traditional sectors. The four sectors underpinning a stronger outlook for the copper market are: the rapid expansion of data centers; geopolitical tensions ratcheting up spending on defense and boosting infrastructure resilience; low-carbon energy projects consuming record amounts of copper; and Southeast Asia and India becoming major consumers of copper as they rapidly industrialize.

Data centers: Gluttons for power, water and minerals Part I

Data centers: Gluttons for power, water and minerals Part II

I previously wrote about data centers as gluttons for power, water and minerals. The capex on data centers by tech companies intent on staying ahead of the AI boom is truly remarkable. According to Statista,

Last year alone, Meta, Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft spent more than $400 billion in capital expenditure, most of it dedicated to building the data centers that are the foundation of all AI applications. That’s more than double the amount spent in 2023 and yet, there is no end in sight to what experts are calling the “AI arms race”. According to the companies’ latest CapEx spending forecasts, their joint investments will easily exceed $600 billion this year, with Amazon alone expecting to spend $200 billion on “seminal opportunities like AI, chips, robotics, and low earth orbit satellites.”

Woodmac notes that to meet forecasted copper demand, the industry will need to bring new mines online at roughly twice the rate of a decade ago. The problem is that greenfield mines/ new discoveries are failing to keep pace.

It explains that Western miners remain cautious about committing capital to new mine supply, even as prices rise.

Why Copper Incentive Pricing and increasing M&A matters to owners of BC copper and gold projects

“This isn’t about geology. We identify a robust pipeline of greenfield projects. The challenges, particularly for Western miners, are far more about investment and risk appetite,” the blog states.

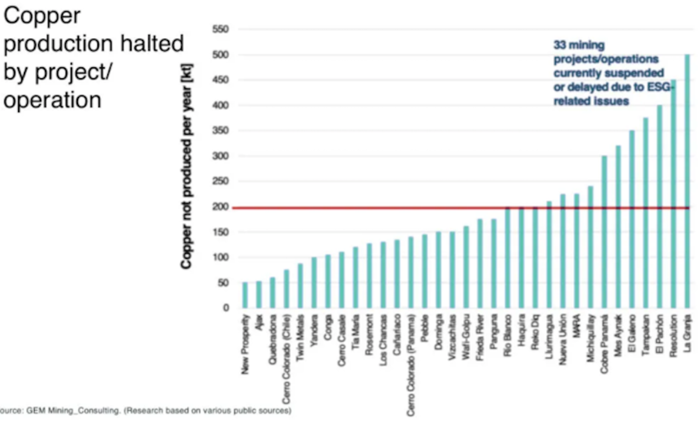

Instead of investing in Greenfields exploration and development, Western miners are instead focusing on sustaining output. However, key constraints include strict capital discipline and heightened ESG requirements.

Financial hurdles are also a consideration, says Woodmac, noting that new copper mines require billions of dollars in upfront capital and that Western miners typically rely on private debt, “with providers imposing increasingly demanding conditions. Some financing terms include stress tests at copper prices 20% to 30% below our forecasts.”

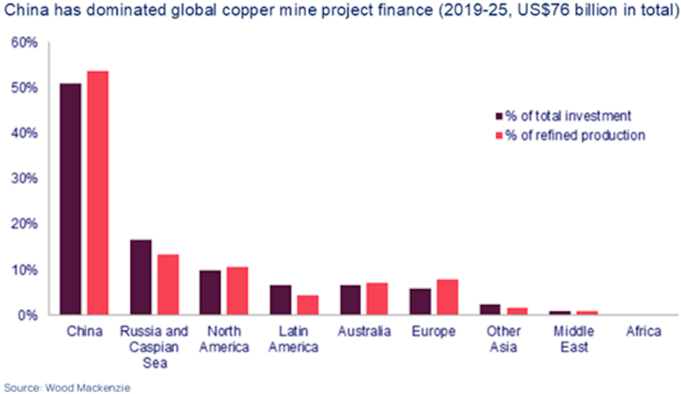

In contrast, “Chinese miners are seizing an opportunity to fully integrate value chains and increase their influence over global copper flows as demand accelerates.”

“Unlike their Western counterparts, Chinese miners have aggressively pursued opportunities in higher-risk jurisdictions. Of the US$76 billion invested globally in green and brownfield copper supply between 2019 and 2025, around 50% came from Chinese miners.”

This approach has enabled China to dominate copper and cobalt production in the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example.

Wood Mackenzie estimates that 8Mtpa of new mining capacity, in addition to 3.5Mt of copper scrap, will be required to balance the market in 2035. The cost to deliver this supply growth is likely to exceed $210 billion, compared to around $76 billion invested in copper mining over the past six years.

Still more research into the copper supply comes from the International Institute for Strategic Studies, or IISS.

The institute says that disruptions to mine output, a collapse in refining margins and stockpiling by the United States have pushed the global copper market into a period of sustained strain.

Copper mining faces challenges in the form of resource nationalism, environmental regulation, adverse weather and public opposition. Due to these factors, it is likely that the market will move into a structural deficit in the 2030s. While 2025 mine disruptions such as the Grasberg mud intrusion that has temporarily shut down the second-largest copper mine in the world, and earthquake-caused flooding at the Kamoa-Kakula mine in the DRC, will likely create a market deficit in 2026, IISS does not expect a severe near-term shortfall.

Production failures

We get a better idea of why mines aren’t hitting their production targets by examining the situation in Chile. Other major producers, including Peru, Indonesia and the DRC, are running into trouble.

Bloomberg reports that Chile, the world’s top copper producer accounting for 25% of global supply, saw output declines for each of the last five months of 2025:

Chilean copper mines have been hit by setbacks at projects that are key to tapping richer areas of deposits, while a mine run by Capstone Copper Corp. struggled with a strike and the giant Quebrada Blanca mine is battling waste-storage issues.

Other disruptions included a rock burst at El Teniente last July that caused 48,000 tons of lost production in 2025 and likely another 25,000 tons in 2026; and contract workers that blockaded access roads to Escondida — the world’s largest copper mine — and the Zaldivar mine.

Another source, The Oregon Group, says that state-owned copper miner Codelco managed to eke out a 0.3% increase in 2025 over 2024, but notes that average copper grades have fallen from 1.02% to 0.66% in 2025. That’s almost a 50% reduction in grade.

Peru, the number 3 producer, also saw a number of setbacks. Output last year declined 12% to 216,152 tonnes, owing to social unrest at MMG’s Las Bambas mine and Hudbay Minerals’ Constancia. At Constancia informal miners staged protests over stricter permit rules, blocking key transport routes and disrupting operations. Informal miners were also behind intermittent road blockages at Las Bambas aimed at preventing ore-laden trucks from reaching the coast.

I’ve already mentioned the ongoing closure of Grasberg in Indonesia and the temporary halt in production at Ivanhoe Mines’ Kamoa-Kakula complex in the DRC. Kamoa achieved its 388,838-ton guidance in 2025 but will have to push back its 500,000-ton target to 2027.

More bad news for the Congo’s copper: the country will reportedly “enforce a long-dormant rule requiring local employee ownership for mines in a move that may rebalance shareholdings in some of the world’s biggest copper and cobalt producers.

“In a letter dated Jan. 30 and addressed to miners of all metals in the country, Mines Minister Louis Watum said firms must demonstrate that 5% of their share capital is held by Congolese employees.”

Zambia, African’s second-largest producer, missed its million-ton government target in 2025, having to settle for 890,346 tonnes. According to The Daily Brief,

Growth at Mopani and Konkola was offset by a tailings dam collapse in February 2025 and an 18% production decline at the Trident mine due to lower grades. The country aims for 3 million tons by 2031, but current operational hurdles highlight the difficulty of scaling in high-risk jurisdictions.

In total, an estimated 6.4 million tonnes of copper production capacity, equal to more than 25% of global mine output, is stalled or suspended due to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues, a study by GEM Mining Consulting reveals.

Technical issues

Most of the low-hanging copper fruit has been identified and mined. What’s mostly left is copper in hard-to-reach places with little to no mining infrastructure and/or it’s in politically risky jurisdictions where a mining project can be expropriated at the whim of a government.

Decades ago, the best copper mines had grades of 1.5% or higher. Today, many mines operate below 0.6%, meaning operators must dig up twice the amount of rock to obtain the same amount of copper.

Climate is another problem. In Chile, most of the mines are in the Atacama Desert, but copper processing is water intensive. Water is needed to separate copper from rock, keep the dust down, and to cool equipment. Making matters worse, Chile is experiencing a “megadrought” that has lasted over 15 years.

Some mines have had to cut production, while other are spending billions of dollars to build desalination plants on the coast and pump seawater hundreds of kilometers uphill into the mountains.

Market tightness and US stockpiling

A year ago, the copper market was shaken by the prospect of tariffs on copper imported into the United States. However, industry fears were quelled when in late July, President Trump announced 50% tariffs only on semi-finished copper products, with refined copper and the raw materials produced by mines — cathodes and concentrates — provisionally excluded.

Meanwhile, stockpiling in the US has deprived the rest of the world of available copper.

Between last February and late July, US copper imports soared, as shippers strove to get their copper to the US ahead of the expected tariffs. This increased stocks on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), which elevated prices. For a few months, US copper prices traded at a significant premium to LME prices.

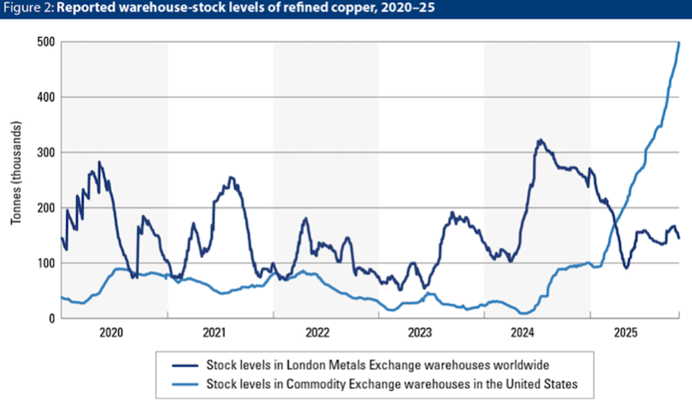

IISS notes the lingering threat of copper tariffs has meant that US-held stocks continued to climb since July, and domestic prices remained at a premium until the start of 2026, as the graph below shows.

The country imported 1.7 million tonnes of copper last year, according to the US Geological Survey, almost double the volume from 2024.

As for the stockpile, Bloomberg reports that copper held in exchange-approved warehouses, which back futures contracts, have climbed relentlessly since early 2025. As of Feb. 6, 2026, inventories stood at 589,081 tons, a more than five-fold increase from a year earlier.

As mentioned, the copper flowing into the US has tightened supply for the rest of the world. For example, copper fabricators in China have struggled to source feedstock and are passing the higher costs onto consumers, chilling industrial demand for the metal.

Between tight supply and mine disruptions, copper has soared to record highs.

What would happen to the copper stockpile if US tariffs on refined copper fail to materialize and copper floods the global market, depressing prices?

While analysts and traders initially feared this could happen, according to Bloomberg views have now shifted towards an even larger stockpile, as the US government and companies look to protect the country’s manufacturing base from scarce supply, volatile prices and over-reliance on imports from China.

Copper was declared a critical mineral by the US in November 2025, and the administration has plans to create a $12 billion stockpile of critical minerals known as “Project Vault”.

The United States is also buying into mines directly. Recently Glencore announced it is selling a 40% stake in its DRC copper and cobalt mines to a US-backed critical minerals consortium.

“Orion CMC will have the right to… direct the sale of the relevant share of production from the assets to nominated buyers, in accordance with the U.S.-DRC Strategic Partnership Agreement, thereby securing critical minerals for the United States and its partners, reads a Feb. 3 press release.

All of this is to try to loosen the chokehold China has on critical minerals like cobalt and copper. But China is also stockpiling critical minerals and has done for years. Earlier this month a metal association in China called for the government to stockpile copper — a necessary step to avoid concentrate shipments from being disrupted and risking smelters from going idle. Remember, China consumes half the world’s copper and processes 57% of global refined supply.

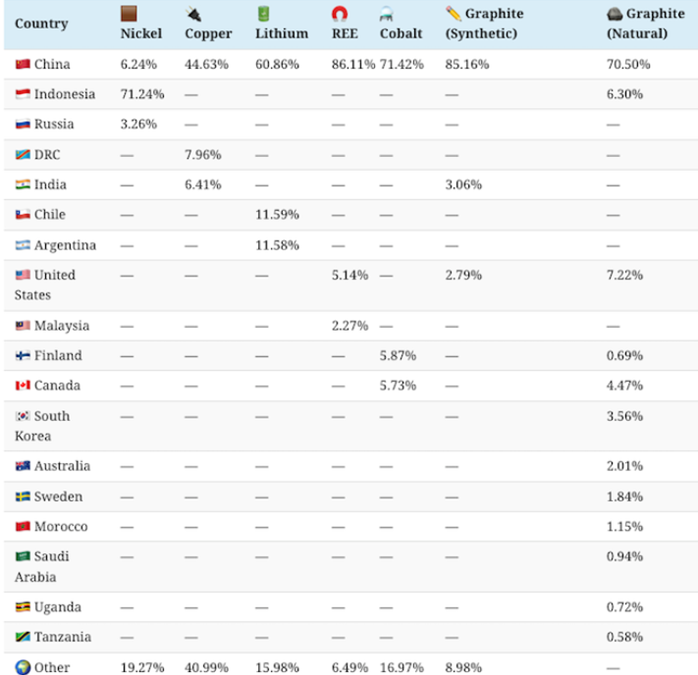

In fact, China is expected to have the largest share, at 60%, of global refined critical metals supply by 2030. Although it should be noted that copper refining is more diversified than, say, rare earths elements, for which China controls 86.1% of refining, compared to copper’s 44.6%.

Other refined minerals heavily weighted towards China include lithium (60.8%), cobalt (71.4%), natural graphite (70.5%) and synthetic graphite (85.1%), as shown in the table below.

M&A over Greenfields

According to the International Energy Agency, via Reuters, the capital expenditures (capex) required to get new supply up and running in Latin America, the nexus of global copper production (Chile, Peru), has increased 65% since 2020.

To build a new 200,000-ton-a-year copper mine, the upper end is $6 billion.

That implies up to $30,000 to build one ton of yearly copper production, a figure miners are not, so far, buying into.

It’s easy to see why miners are reluctant to build new mines and are instead relying on mergers and acquisitions to increase their reserves.

Recent examples include the merger between Anglo American and Canada’s Teck Resources to form a new company, Anglo Teck; BHP and Lundin Mining’s $38 billion joint venture to expand the Filo del Sol Project in Chile/ Argentina; and MMG acquiring Cuprous Capital to expand the Khoemacau copper mine in Botswana.

Codelco and Anglo American last September finalized an agreement to merge operations at their Los Bronces and Andina copper mines.

The Anglo-Teck merger made sense because Anglo’s Collahuasi mine and Teck’s Quebrada Blanca mine are just 15 kilometers apart in Chile’s Atacama Desert. By combining processing facilities and sharing resources, they expect to produce more copper more efficiently.

Many copper mines are decades old and reaching the end of their lives. Their owners can expand them vertically, such as Newmont-Imperial Metals’ underground block cave operation at their Red Chris mine in northwest British Columbia, try to find more copper around the mine, or the most attractive option, buy other copper miners’ and add their reserves to your own.

Copper mining companies prefer the last option rather than try to find new mines. It’s the path of least resistance. It takes a long time to build a new copper mine as mentioned the timeline from discovery to production spans 17 years.

In the United States it’s upwards of 30 years, which is frankly ridiculous. Permitting alone can take seven years. Even after a mining company gets the required permits, environmental and indigenous groups, or local governments, can challenge a project in court, further delaying the process.

Take the Resolution project in Arizona. As one of the largest undeveloped copper deposits in North America, Rio Tinto and BHP have been trying to develop it for decades, spending $2 billion thus far. But as the Daily Brief reports,

Due to legal challenges, environmental reviews, and political battles, not a single gram has been mined.

This is increasingly the norm, despite big deposits existing. Getting from discovery to production is so slow and risky that many projects never get built.

Unfortunately, M&A this does nothing to alleviate the global copper supply deficit. It’s just shifting one pile of reserves in one mining company to another. The global reserves total doesn’t change. The deficit continues.

All it takes is one major copper mine to get shut down, and suddenly we’re looking at deficits. Electrification, AI, and all the above listed uses of copper are putting strains on the copper supply.

The obvious solution is to find more copper.

What companies are saying

Ivanhoe Mines wrote that “Copper deficits are increasing. By 2040, demand is set to jump by around 9 million tonnes, while supply is expected to drop by about 1 million tonnes… a shortfall of roughly 10 million tonnes.”

On Feb. 5 Anglo American posted a 10% drop in production in 2025 to 695,000 tonnes, the lower end of its guidance, and cut its 2026 copper production forecast. Reuters reported the London-listed miner expects this year’s output of between 700,000 and 760,000 tons, from a previous forecast of 760,000 to 820,000 tons, partly due to lower production from its Collahuasi mine in Chile.

Anglo also said it expects to record around $200 million in charges for the second half of 2025 related to rehabilitation provisions at its Chile copper operations.

Despite operational problems, mining stocks are suddenly in vogue again. A recent Bloomberg article said global miners have “shot to the top of fund managers’ must-have list, as soaring metals demand and tight supplies of key minerals hint at a new super-cycle in the sector.”

With a nearly 90% gain since the start of 2025, MSCI’s Metals and Mining Index has beaten semiconductors, global banks and the Magnificent Seven cohort of technology stocks by a wide margin. And the rally shows no sign of stalling, as the boom in robotics, electric vehicles and AI data centers spurs metals prices to ever new highs.

That’s particularly true of copper, which is key to the energy transition and has surged 50% over the same period.

According to Bank of American’s monthly survey, European fund managers now are 26% overweight on the sector, the highest in four years, though well below the 38% net overweight in 2008.

Yet the sector looks undervalued. Bloomberg reports The Stoxx 600 Basic Resources index trades at a forward price-to-book ratio of about 0.47 relative to the MSCI World benchmark. That’s an about 20% discount to the long-term 0.59 ratio and well below prior cycle peaks above 0.7.

“This valuation gap persists even as the strategic relevance of natural resources has risen materially,” Morgan Stanley analysts led by Alain Gabriel wrote.

Conclusion

The picture emerging is a world that needs a lot more copper than it currently produces.

Supply disruptions at several large copper mines have pushed the market into deficit this year. Copper supply is expected to fall 10Mt short of demand by 2040, putting at risk industries such as artificial intelligence, defense spending and electrification — all of which are driving demand higher.

Wood Mackenzie estimates that 8Mtpa of new mining capacity, in addition to 3.5Mt of copper scrap, will be required to balance the market in 2035. The cost to deliver this supply growth is likely to exceed $210 billion, compared to around $76 billion invested in copper mining over the past six years.

But copper is getting more expensive to dig out of the ground. Ore grades are declining, and water needed for mining is getting scarce, especially in Chile, which is in a multi-year drought. Energy and labor costs are also pushing expenditures higher.

Governments are starting to realize the problems in the copper industry and have made copper a critical metal. The United States and are countries have begun stockpiling copper, signaling a fear of running out of the electrification metal. US stockpiling has further tightened an already tight copper market.

Governments are investing in copper mines to gain some control over the copper supply chain, which is vulnerable to disruptions.

Companies are merging to control what copper is left, taking the path of least resistance by shifting reserves from one balance sheet to another rather than taking the time and allocating funds to discovering new copper deposits. It takes up to 30 years to develop a new copper mine from discovery to production in regulation-heavy jurisdictions like Canada and the United States. This must change, or the copper supply deficit will only get worse.

I’ve been predicting it for years, but the scramble for copper is finally here. And it’s just getting started.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.