Why the upcoming copper supply deficit can’t be easily fixed – Richard Mills

2022.12.09

Some of the largest copper mines are seeing their reserves dwindle; they are having to slow production due to major capital-intensive projects to move operations from open pit to underground. Examples include the world’s two largest copper mines, Escondida in Chile and Grasberg in Indonesia, along with Chuquicamata, the biggest open-pit mine on Earth.

Bank of America in a recent report predicts the copper market will flip into a deficit as early as 2025 following the completion of the current wave of project buildouts, the latest being Ivanhoe Mines’ massive Kamoa-Kakula project in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Five years later, analysts at Rystad Energy project that copper demand will outstrip supply by more than 6 million tonnes. That equates to nearly the entire annual production of Chile, the world’s top producer.

By 2040, the annual supply shortfall grows to 14Mt, according to a BloombergNEF August report, with a “best-case scenario” shortage of >5 million short tons possible by 2040.

Copper fundamentals strong despite price weakness

In fact we don’t have to wait, to see signs of an emerging copper crisis. Some of the world’s largest copper miners this year have proven unable to produce as much as they said they would. BHP, Rio Tinto, Anglo American, First Quantum Minerals and Glencore have all pared back production forecasts, blaming higher costs for their lower output figures.

Following a 14% drop in copper production in Q1, Glencore cut its 2022 guidance by 3% or 40,000 tonnes.

The company’s CEO, Gary Nagle, recently added his voice to a chorus of large mining companies warning of a coming copper shortage, saying that, while some people were assuming that the industry would simply ramp up supply as it had in previous cycles to meet higher forecasted demand, driven by electrification and decarbonization trends, “this time is different”. (Bloomberg, Dec. 6, 2022)

He presented estimates showing a cumulative gap between projected demand and supply of 50 million tons between 2022 and 2030. That compares with current world copper demand of about 25 million tons a year.

“There’s a huge deficit coming in copper, and as much as people write about it, the price is not yet reflecting it,” Nagle said.

If what Nagle says is true, then over the next eight years, to close that 50Mt supply gap, the mining industry will need to produce an additional 6.25 million tons of copper per year, on average.

There are really only three ways for the industry to get this additional metal. First, they can increase production from existing mines; this often involves “going underground”, digging beneath the existing open pit to access more ore. An expansion to the existing concentrator or building a new one, is sometimes needed.

Second, they can expand their mines laterally, going after resources that weren’t part of the initial mine plan because they were less accessible, or un-economic. Third, they can explore for new mineral deposits, either internally, or working with junior mining companies, which have the exploration expertise to bring a deposit forward to the point when it can be sold to a major. Obviously option three, known as greenfield exploration, is more difficult, costly, and carries higher risk than options one and two, called brownfield exploration.

Over the past 10 years, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically. S&P Global estimates that new discoveries averaged nearly 50Mt annually between 1990 and 2010. Since then, new discoveries have fallen by 80% to only 8Mt per year.

In fact, most of new copper supply is concentrated in just five mines — Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC.

What about the rest of the copper pipeline? Surely there are more deposits containing copper, a mineral that is relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust, and has been mined in open pits for centuries, than the five mines we’ve mentioned above.

There are, and they’re summarized in a 2018 report by Goldman Sachs, titled ‘Copper Top Projects’. AOTH wanted to know, four years later, how many of these projects actually produced any new copper, and how close these projects will come to bridging the 50-million-ton supply gap estimated by Gary Nagle to be facing the industry between now and 2030. Remember, that’s an average 6.25Mt of new supply, every year, for the next eight years. Current mine production is 21Mt a year and annual copper demand is pegged at 25Mt (difference made up by recycling).

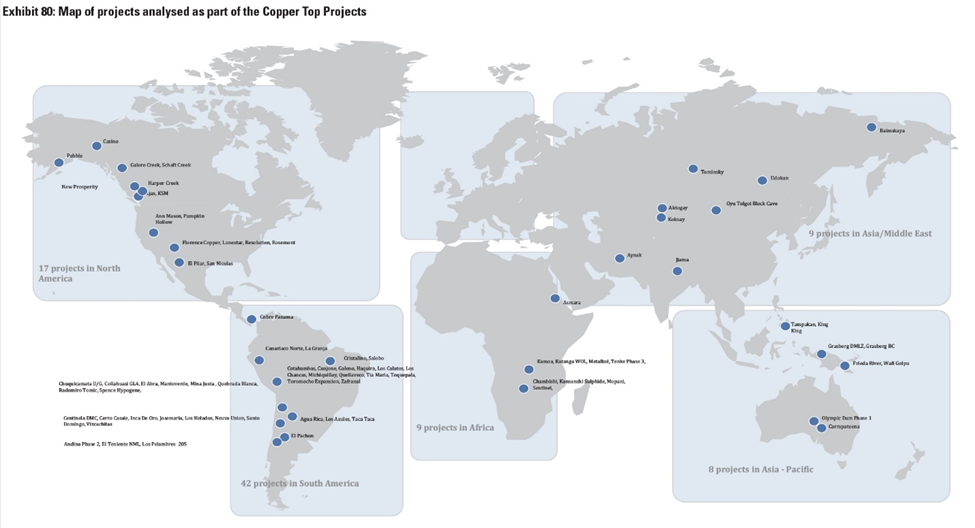

We’ll start by presenting the 84 projects Goldman analyzed for its report. On the map below, you see them as blue dots clustered among five regions. The majority, 42, are in South America, unsurprisingly, since Chile and Peru are the world’s top two copper-mining countries. North America is next with 17 Copper Top Projects analyzed, followed by nine projects each in Africa and Asia/Middle East, and eight projects in Asia Pacific, including Australia.

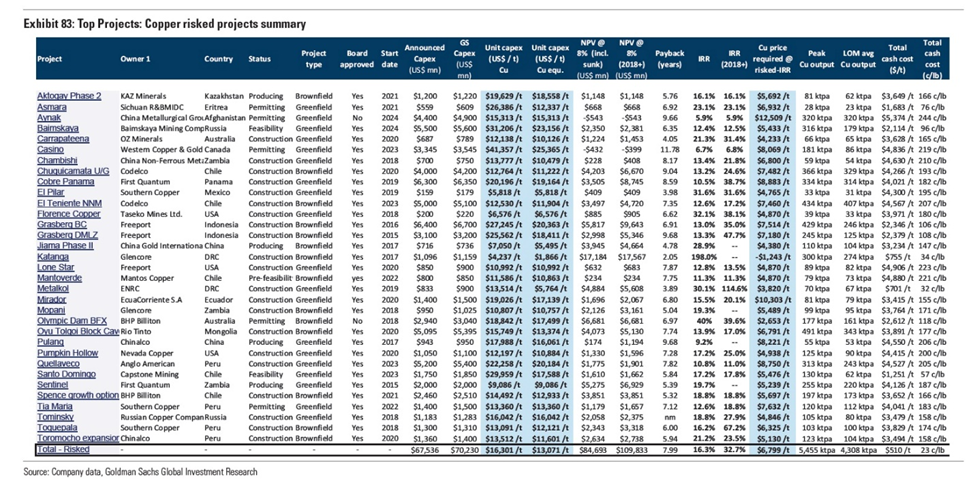

Goldman compiles the data into three tables, found on pages 95, 97 and 98 (Exhibits 81, 83 and 84), click on the individual tables to see an enlarged view.

The first thing to notice, is that when the life of mine (LOM) production of all 84 projects it totaled, it comes to 13,159ktpa (kilotonnes per annum – could also be written as 13.159Mt (million tonnes).

If all 13Mt of mine supply came to market at once, it would fill just over a quarter of the 50Mt projected supply gap. But this is over life of mine, meaning anywhere from 0 (mine already in production) to 25 years into the future.

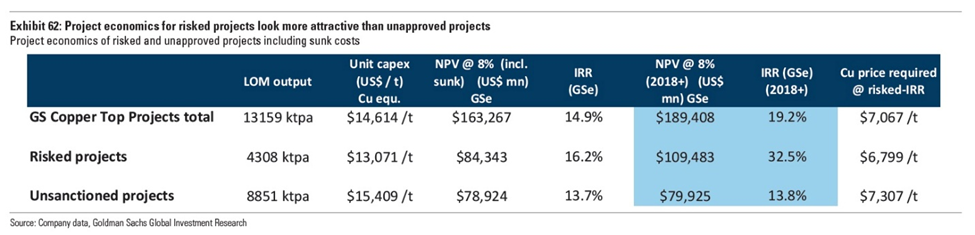

Goldman then separates the 84 projects into 33 “risked projects” and 51 “unapproved projects”, with LOM cumulative production of 4,308ktpa and 8,851ktpa, respectively. The risked projects (mostly board approved), are farther along the path to development, with most, as of 2018, in construction, permitting or feasibility, than the unapproved projects of which many are greenfield and in the scoping study and prefeasibility stages.

Goldman notes that, of the risked projects, there are 23 where some capital expenditures (capex) has been spent by companies and the mines are either ramping up or beginning to ramp up, versus 10 projects where capex has yet to be spent (again, as of 2018).

Upon further examination of this “risked projects” data set, we noticed that 19 are greenfield (i.e. in areas that have never been mined) and 14 are classified as brownfield. There are 21 projects in the construction phase, five in permitting, two in feasibility and one in prefeasibility.

Fast forward four years, to 2022.

Out of 21 projects in construction in 2018, 17 have started producing, bringing to market 2,927ktpa of new copper supply, or 2.9 million tonnes.

Eight were expansions of existing mines, i.e. not new production, one was a restart of an existing mine, and three have yet to start production. Those three represent a total of 407ktpa.

Of the projects in the permitting stage, four out of five have yet to start producing (only one, Asmara in Eritrea, made it into production), leaving 679ktpa out of the mix.

Two of the risked projects had reached the feasibility stage in 2018, but neither are producing in 2022. The one project in prefeasibility, Mantoverde in Chile, also has not reached production. Combined, this amounts to 314ktpa.

So out of a total LOM average copper output of 4.3Mtpa, 2.9Mtpa of new supply has come to fruition in 2022; 1.4Mtpa failed to reach production.

But, of the 2,927ktpa, we should subtract the production from the eight projects that are underground expansions of existing mines, and the restart of an old mine, Katanga in the DRC. They represent a total of 1,728ktpa, leaving actual “new” copper supply of just 1,199ktpa.

Why don’t we count production from these mines? Well, the reason they are going underground, is because the open pit has become mined out.

Whatever amount of production they lost due to depletion, they plan to gain it back by digging deeper into the deposit. This is production that is already “in the market”; all they are doing is maintaining existing production rates by replacing ore previously mined from the open pit, with ore from underground.

For example, in 2020 Codelco began underground operations at its Chiquicamata Mine in Chile, using the block caving technique. Annual production was projected to be 320,000 tonnes of copper and 15,000 tonnes of molybdenum.

Of the three mines under construction in 2018 that in 2022, still weren’t in production:

- Grupo Mexico’s El Pilar in Sonora State is expected to bring 36,000 tonnes online by the second quarter of 2023;

- Taskeo Mines said its Florence copper project in Arizona has recently concluded the public comment period required by the EPA, which must issue the final Underground Injection Control (UIC) permit. The company says the project when ramped up will produce 40,000 tonnes of cathode copper annually.

- The underground expansion of Oyu Tolgoi in Mongolia, known as Oyu Tolgoi Block Cave, continues to be beset by delays and cost over-runs. The underground section is expected to lift production from 125,000–150,000 tonnes in 2019 to 560,000 tonnes at peak output, which is now expected by 2025 at the earliest.

The two projects at the feasibility stage in 2018 still aren’t in production:

- The forecasted capex for Kaz Minerals’ +20 year Baimskaya project in Russia is a whopping $8.5 billion. Kaz expects it to start by 2028, producing an annual 300,000 tonnes of copper and 490,000 oz of gold during the first 10 years of operation.

- Capstone Copper is targeting 200,000 tpa of copper from its fully permitted Santo Domingo Mine in Chile. After completing its Mantoverde Development Project, Capstone says its next step is “a construction decision and integration of Santo Domingo.” The mine’s first oxide mineral resource is due in the second half of 2023, to be followed by an updated feasibility study.

Of the four projects at the permitting stage in 2018 that in 2022, still weren’t in production:

- In 2017, nine years after Chinese companies took control of the Mes Aynak Mine in Afghanistan, copper extraction has yet to start. “Due to the unstable situation in Afghanistan, the Mes Aynak copper mine invested by the company has not yet undergone substantial construction,” Zheng Gaoqing, the chairman of Jiangxi Copper, said at an online briefing in 2021.

- Western Copper & Gold has been in discussions with the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board (YESAB) about its Casino copper-gold project in the Canadian Yukon Territory, since the original guidelines were issued in 2016. The company put out a feasibility study earlier this year envisioning annual production of 163 million pounds copper, 211,000 oz gold, 1.28 million oz silver and 15.1 million lb molybdenum.

- The copper resource at the Olympic Dam BFX project in Australia is considered the world’s fourth largest. However in 2020, after three years of study and more than 400 kilometers of drilling, BFX was axed. “The studies have shown that the copper resources in the southern mine area are more structurally complex, and the higher grade zones less continuous than previously thought,” according to BHP’s quarterly production review.

- Southern Copper, a subsidiary of Grupo Mexico, has faced a number of setbacks at the long-delayed $1.4B Tia Maria copper project in Peru. Construction plans have been halted and readjusted twice, due to strident and at times deadly opposition by locals, who worry about Tia Maria’s impacts on nearby crops and water supplies. The country’s economy and finance minister in 2021 said he believed the proposed mine was “socially and politically” unfeasible.

According to Goldman Sachs’s 2018 report, the incentive copper price required to bring the 33 risked projects (projects that have been board-approved) is US$6,799/t, and to bring the 51 unapproved projects online, it’s $7,307/t. This compares with the October 2018 spot copper price of US$6,250/t.

The incentive price to make mining copper attractive is now US$9,000 a tonne – copper is trading currently at US$8,487/t. So do these 2022 higher prices mean that the 2018 numbers are now economic? For some yes, for most no.

Going back to Exhibits 83 and 84, Goldman’s list of risked projects and unapproved projects, we see a number with a required copper price above $9,000 a tonne. These mines were uneconomic to put into production in 2018, and they would still be; they need a higher price.

For example, Aynak @ $12,509/t, Mirador $10,303, Centinela DMC $9,122, Cerro Casale $9,964, El Pachon $10,029, Josemaria $10,971, and King King $12,706.

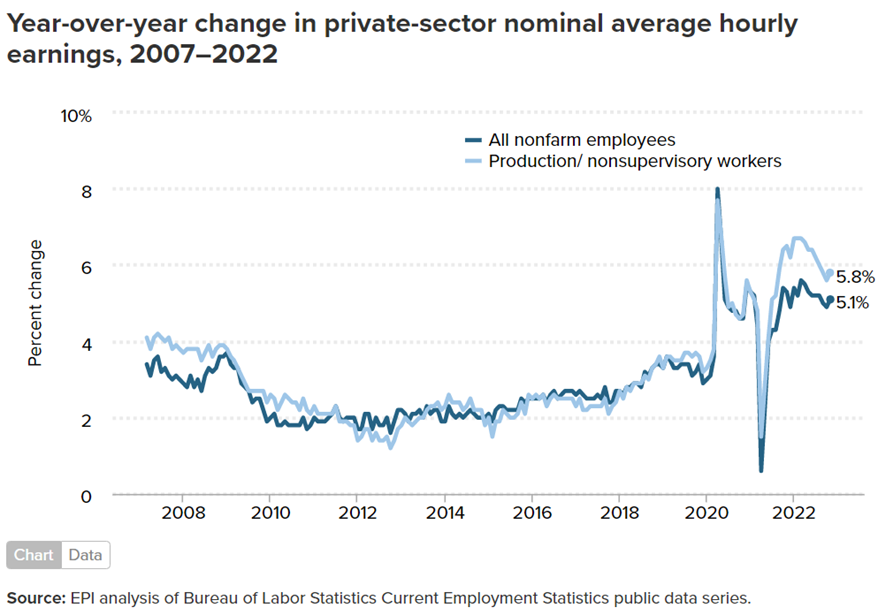

Any project that didn’t meet the 2022 incentive price in 2018 likely won’t do it in 2022. While copper has gone up from US$6,250/t at the time of Goldman’s report, to around $8,500 currently, mining costs are through the roof. Capital inputs account for about half the total costs of mine production — the average for the economy as a whole is 21% and copper processing operations are some of the most water and energy-intensive within the mining industry.

As we noted in a previous article copper mining is an extremely capital-intensive business for two reasons. First, mining has a large up-front layout of construction capital called capex – the costs associated with the development and construction of open-pit and underground mines. There is often other company-built infrastructure like roads, railways, bridges, power-generating stations and seaports to facilitate extraction and shipping of ore and concentrate. Second, there is a continuously rising opex, or operational expenditures. These are the day-to-day costs of operation: rubber tires, wages, fuel, camp costs for employees, etc.

The average capital intensity for a new copper mine in 2000 was between US$4,000-5,000 to build the capacity, the infrastructure, to produce a tonne of copper. In 2012 capital intensity was $10,000/t, on average, for new projects. Today, building a new copper mine can cost up to $44,000 per tonne of production.

Capex costs are escalating because:

- Declining copper ore grades means a much larger relative scale of required mining and milling operations

- A growing proportion of mining projects are in remote areas of developing economies where there’s little to no existing infrastructure.

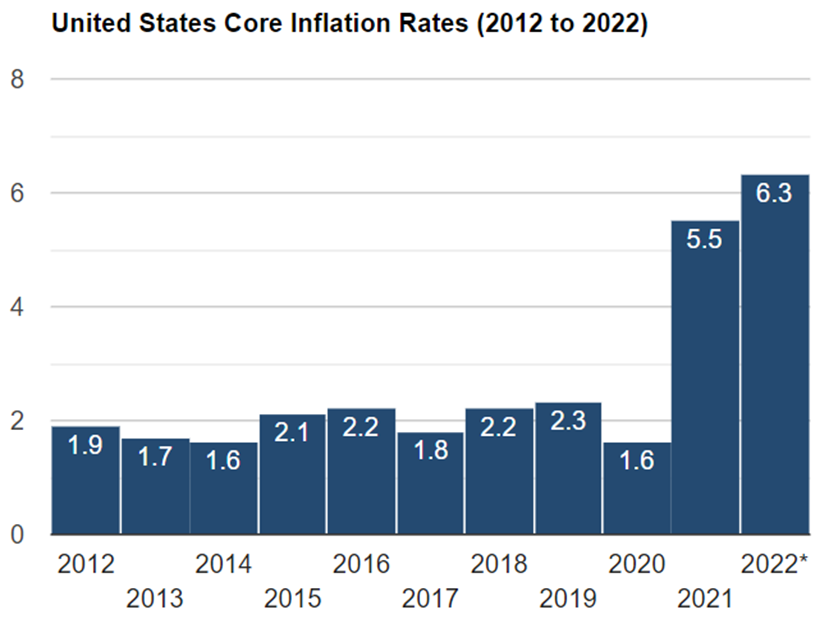

Many inputs necessary for mine-building are getting more expensive, as cross-the-board inflation, the highest in 40 years, infiltrates the industry. This includes two of the largest costs, wages and diesel fuel, used to run mining equipment.

The bottom line? It is becoming increasingly costly to bring new copper mines online and run them.

Investors are also demanding a higher return on investment than previously, when there was a greater appetite for risk.

After the last commodities boom came to an abrupt halt in the mid-2010s, several mining companies savaged by plummeting metals prices were forced to take billion-dollar write-downs and enact fiscal discipline amid shareholder pressure.

Personally I want to see a minimum four-year payback on my investment, meaning at least a 25% internal rate of return (IRR). Scanning Goldman’s list of copper projects, we see few above our 4-year payback threshold, most are below it.

And this is on the risked projects list. Only six of these 33 mining projects meet our criteria of an IRR above 25%. Just three have a payback under four years.

Out of 51 unapproved copper projects, just two have IRRs above 25%, and only three have paybacks under four years. One of the projects on this list, Freeport’s El Abra in Chile, actually has a negative internal rate of return!

The average IRR for the 31 risked projects is a disappointing 16%, unapproved projects a dismal 13.8%.

Core CPI between 2018 and 2022 went up 17.90% (Core CPI strips out food and energy). The average IRR (risked projects 16%, unapproved 13.8%), for all projects on Goldman’s list is well below the level of inflation.

Another red flag is the copper mine expansions. A brownfield project should have a better IRR and a shorter payback period than a greenfield because all the mining infrastructure is already in place. We are surprised to see such low IRRs for these brownfield copper projects.

Conclusion

In recent years, the global transition towards clean energy has stretched the need for copper. More of it will be required to feed our renewable energy infrastructure, such as photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines.

The metal is also a key component in transportation, and with increasing emphasis on electrification, demand is only going to increase.

But the copper market is facing a serious crisis of under-supply.

Some of the largest copper mines are seeing their reserves dwindle; they are having to slow production due to major capital-intensive projects to move operations from open pit to underground.

New deposits are getting trickier and pricier to find and develop. In Canada and the United States, there is a lot of anti-mining sentiment and politicians are beholden to these pressure groups. It can take up to 20 years to build a mine, after all the stakeholders (including indigenous peoples and greens) have been consulted and the many permitting requirements, at the Federal level in both countries, and the states and provinces have been satisfied. Overall it is getting harder, and taking longer, for new projects to be green-lit.

According to Goehring & Rozencwajg Associates, the number of new world-class copper discoveries coming online this decade “will decline substantially and depletion problems at existing mines will accelerate.”

E&MJ Engineering stated in its outlook for copper production to 2050, “The trend toward declining orebody grades and continued development of the pursuit of existing operations to exploit lower grade deposits is likely to continue, in the absence of high-grade project discovery.

A decline in ore grade results in higher operating costs due primarily to the amount and depth of material required to be mined and processed to produce the same amount of copper product. It is no surprise that both GHG emission intensity and energy intensity increase as ore grade decreases. There is a point of inflection, where below an ore grade of around 0.5% copper, the intensity of both metrics rises sharply.”

Given that many mines are fast approaching, if not already tackling, similar grades, this is a pressing problem. In its fiscal year 2020 commodity outlook, BHP, the world’s third largest copper producer, estimated that grade decline could remove about 2 million metric tons per year (mt/y) of refined copper supply by 2030, with resource depletion potentially removing an additional 1.5 million to 2.25 million mt/y by this date.”

Along with technical issues such as falling grades/ deteriorating ore quality, there is also supply pressure from growing resource nationalism.

In Chile, a left-ward shift is a mark against the top copper producer as far as attracting mining investment. Although Chile’s constitutional assembly has rejected plans to nationalize parts of the mining sector, the government is now weighing how much to increase royalties; a decision is expected soon.

Peru’s President Pedro Castillo has proposed to raise taxes on the mining sector by at least 3%, which the country’s mining chamber says could cost US$50 billion in future investments. This week, Castillo dissolved congress hours before an impeachment vote, escalating a political crisis in the South American nation. Members of the constitutional court called the move, which is sure to increase doubts about Peru as a mining-friendly jurisdiction, a “coup”.

Given this and all the other supply challenges the copper mining industry faces, it’s hard to disagree with Glencore’s CEO Gary Nagle’s comment that, “There’s a huge deficit coming in copper.”

Chief Executive Officer Gary Nagle said that while some people were assuming that the industry would lift supplies as it had in previous cycles to meet a forecast increase in demand driven by the energy transition, “this time it is going to be a bit different.”

He presented estimates showing a cumulative gap between projected demand and supply of 50 million tons between 2022 and 2030. That compares with current world copper demand of about 25 million tons a year.

“There’s a huge deficit coming in copper, and as much as people write about it, the price is not yet reflecting it,” Nagle said.

The Goldman Sachs’ report we’ve been referencing doesn’t exactly fill us with confidence that the industry will be able to bridge the 50-million-ton gap in production, in the eight years before 2030.

In fact if these 84 projects are all we have imo we’re in serious trouble. Out of a total LOM average copper output of a risked 4.3Mtpa AOTH thinks the reality is “new” copper supply of just 1,199ktpa, that doesn’t bode well for production from the 2018 unapproved projects.

That’s a long way from the new copper supply needed.

A new wave of production is washing through the copper market, thanks to supply additions from Kamoa in the DRC, Quellevaco in Peru, and two mines in Chile — Quebrada Blanca II and Spence NGO — Reuters reported on Thursday, but once it breaks, will it be enough to satisfy what comes afterwards? Not likely.

Those are the projects now ramping up into production but, he warned, “there is nothing coming behind”. (something we at AOTH believe was just proved through our analysis of Goldman’s copper project summaries — Rick]

“Whatever was planned to be built has been built,” Glencore’s CEO Gary Nagle warned analysts on a conference call, via Reuters:

Glencore estimates that if the world is going to meet its net zero emissions targets, it will be cumulatively short of copper to the tune of fifty million tonnes by 2030 as the global pivot towards green energy transition boosts copper usage in grid upgrades, solar panels and electric vehicles.

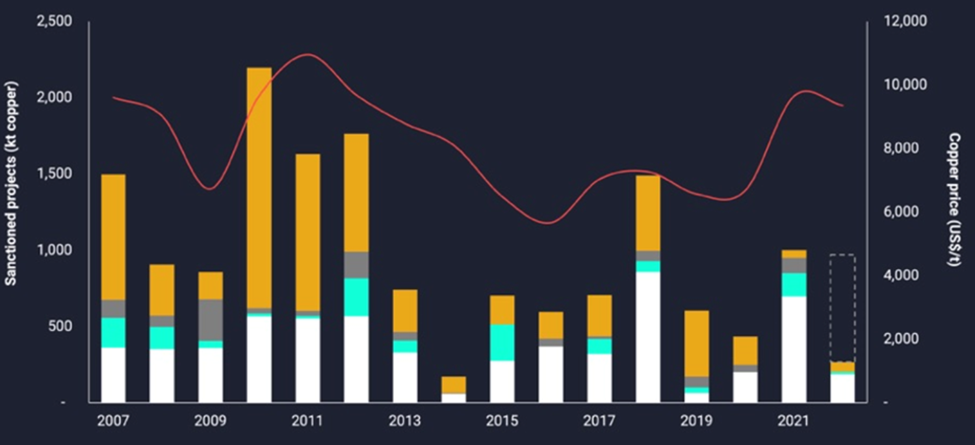

New mines can’t be built and commissioned that fast, even if the will is there. The sector’s low capital expenditures on expanding production suggests many are still loath to commit to the mega-billion investments needed for the next generation of supply.

Of 224 sizable copper deposits discovered in the past 30 years, only 16 have been found in the last decade. Only two major copper mines have been brought online between 2017 and 2021.

At existing mines, between 2001 and 2014, 80% of new reserves came from re-classifying what was once waste rock into mineable ore, i.e., lowering the cut-off grade.

The problem is that between miners lowering their cut-off grades and high-grading (removing all the best ore and leaving the rest) the grade of new reserves each year has steadily declined.

The copper industry was still able to replace all the ore used in production with new reserves, but the quality of those reserves, i.e., the grade, had dropped by nearly two-thirds.

The authors of a 2021 report, Goehring & Rozencwajg, contend that even with prices above $10,000 per tonne, reserves cannot keep growing, specifically at porphyry deposits, where most copper is mined.

Their analysis also suggests that we are quickly approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades, concluding that we are nearing the point where reserves cannot be grown at all.

The industry can no longer re-classify itself out of its problem.

The copper industry is in the grips of a structural supply deficit that is only expected to get worse. An Aug. 31 presentation from BloombergNEF states that a recession will not “significantly dent” consumption projections going into 2040.

The demand pressure about to be exerted on copper producers in the coming years all but guarantees a market imbalance, resulting in copper becoming scarcer, and dearer, with each infrastructure initiative and with each ambitious green initiative rolled out by governments.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.