Why the Fed pivot will happen faster than people think – Richard Mills

2022.12.21

Most market participants see the Fed’s tightening policy as similar to what Paul Volcker’s Fed did in the late 1970s, when double-digit inflation necessitated a cycle of rate hikes that brought the federal funds rate to 20%. Volcker succeeded in taming inflation but the price was the 1982 recession, considered one of the longest and worst in economic history.

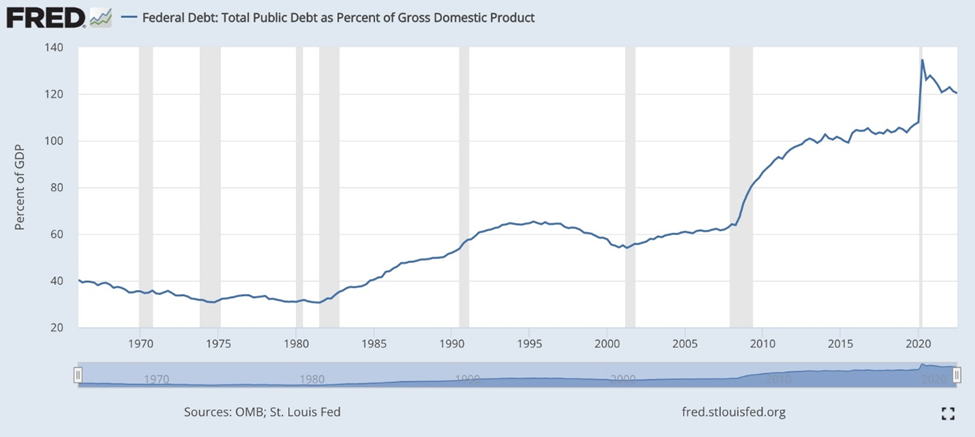

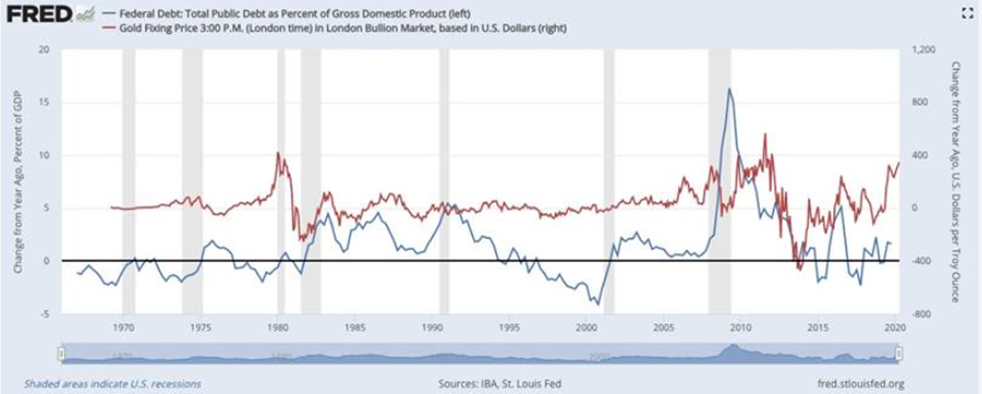

There is one crucial difference between 1982 and 2022, and that is the debt. According to the FRED chart below, the US debt to GDP ratio in 1982 was around 35%. Today it is more than three times higher, at 120%.

This severely limits how much and how quickly the Fed can raise interest rates, due to the amount of interest that the federal government must pay on its debt.

Globally, total private- and public-sector debt as a share of GDP rose from 200% in 1999 to 350% in 2021. The ratio is now 420% across advanced economies, and 330% in China. In the United States, it is 420%, which is higher than during the Great Depression and after World War II.

During 2021, before interest rates began rising, the federal government paid $392 billion in interest on $21.7 trillion of average debt outstanding, @ an average interest rate of 1.8%. If the Fed raises the FFR to 4.6% (it is already @ 4.5% following the 50-basis-points hike in November), interest costs will hit $1.028 trillion (if all debt were to roll-over in the short term) — more than 2021’s entire military budget of $801 billion!

Both political parties have been spending money like a drunken sailor on a Saturday night in Prince Rupert, and must keep doing so, to get re-elected; reducing expenditures (as seen by all the pork in the omnibus US$1.7T massive spending package), is not a solution.

The national debt has grown substantially under the watch of Presidents Obama, Trump and Biden. Foreign wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been money pits, and domestic crises required huge government stimulus packages and bailouts, such as the 2008-09 financial crisis and the covid-19 pandemic in 2020-22.

Each interest rate rise means the federal government must spend more on interest. That increase is reflected in the annual budget deficit, which keeps getting added to the national debt, now at an eye-watering $31.4 trillion.

Considering that egregious over-spending with annual deficits exceeding $1 trillion is likely to continue, the question is who will fund the higher interest costs? The answer is investors, foreign and domestic, who buy US government bonds and notes, issued by the Treasury Department to fund government expenditures.

The problem is that right now, just about everyone is fleeing Treasuries, including emerging markets.

The Fed, the debt, China and gold

Meanwhile, “de-dollarization” is being pursued by countries with agendas at odds with the US, including Russia, China, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Between de-dollarization and investors fleeing Treasuries, the US Federal Reserve will be likely be forced into buying the debt, issued to finance the federal government’s expenditures. (i.e. money-printing)

It must be noted that the majority of this debt is short-term; the vast majority of outstanding US Treasury bonds will mature in the next four years. Former Treasury Secretary Mnuchin tried to extend the duration but there was not enough demand for long-term Treasuries.

One may conclude that the US can easily refinance this debt. I’m not so sure. The lack of Treasury buyer interest is troubling. What happens if Japan China and the UK, respectively the first, second and third largest holders of US Treasuries, continues to offload their holdings? Or if US fiscal deficits balloon further, requiring more Treasury debt to be issued? Will there be enough, or any, buyers?

With over $31T of debt, the US government budget is at great risk of running unsupportable deficits if interest rates continue to increase.

While the market currently doesn’t understand the looming US deficit problem, we believe when it becomes more apparent that the government has a debt-servicing issue and that higher interest rates are making it worse, then demand for US Treasuries will fall even further. Could we be heading for a “no bid” situation like in the UK when buyers for UK gilts completely disappeared?

The key point is, the Fed can only push interest rates so high, without blowing up the Treasury and being forced into an aggressive bond-buying program (QE), thus accelerating inflation. The irony is that in trying to bring down inflation through interest rate hikes, the Fed, because of the high debt levels, will fail, and will be forced into a loose monetary policy involving interest rate cuts and QE. Both would be good for gold.

At AOTH we predicted the 50-bp hike in November and we’ve been saying for months now, that the Fed will relent on its rate hikes early on in the new year, to prevent the economy from falling into recession.

Building our case rests on four conceptual “table legs”, which we will address in turn: 1. History is on the side of the rate hikes stopping; 2. The US economy is in poor condition, especially when it comes to unemployment. This weakens the Fed’s argument for tightening; 3. The rate increases are hitting a wall of debt maturity; 4. The dollar is at risk of being weakened by the Chinese “petroyuan”.

The final Fed rate hike

While the prevailing consensus predicts more interest rate increases in 2023, and no reductions until 2024, there are those who believe that the Fed instead will “hit pause” and begin lowering rates if not during the first quarter then certainly in the second.

Looking at historical data going back to 1972, Bloomberg strategist Peter White found that the last Fed rate hike typically happens about 22 weeks after the peak in CPI.

With inflation peaking at 9.1% in June, that would put the final Fed rate hike around mid-December, which is when the Federal Open Market Committee (on Dec. 14) upped the Federal Funds Rate by 0.5% — breaking a string of four straight three-quarter point hikes.

The first cut then usually takes place 16 weeks later, which according to White’s forecast, puts us into early April, 2023.

Recessionary signals

If you’re not a believer in historical trends, and let’s face it, why would you be, after the trend-busting year we’ve had, then consider the fact that the economy is beginning to show some signs of deterioration.

The Fed is basing the rate hikes on the fact that the economy is able to handle them, but if enough bad economic news transpires, they may have to re-consider their tightening policy, and reverse course quicker than expected.

This is especially the case with respect to inflation and unemployment; the Fed has a dual mandate to control both, typically aiming for a 2% inflation rate and near-full employment.

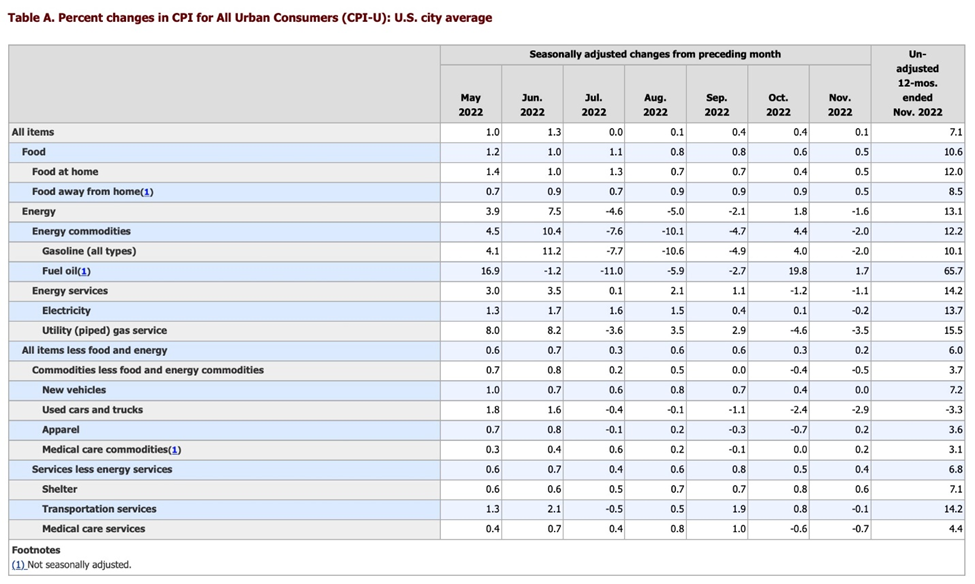

According to Zero Hedge, [Last] week’s [inflation] report showed that the transport component (which was contributing the most to CPI) continues to fall at a rapid clip, overwhelming the steady rise in shelter, and keeping pressure on the headline number.

The Consumer Price Index Summary, released on Dec. 13 by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, states, The all items index increased 7.1 percent for the 12 months ending November; this wasthe smallest 12-month increase since the period ending December 2021.

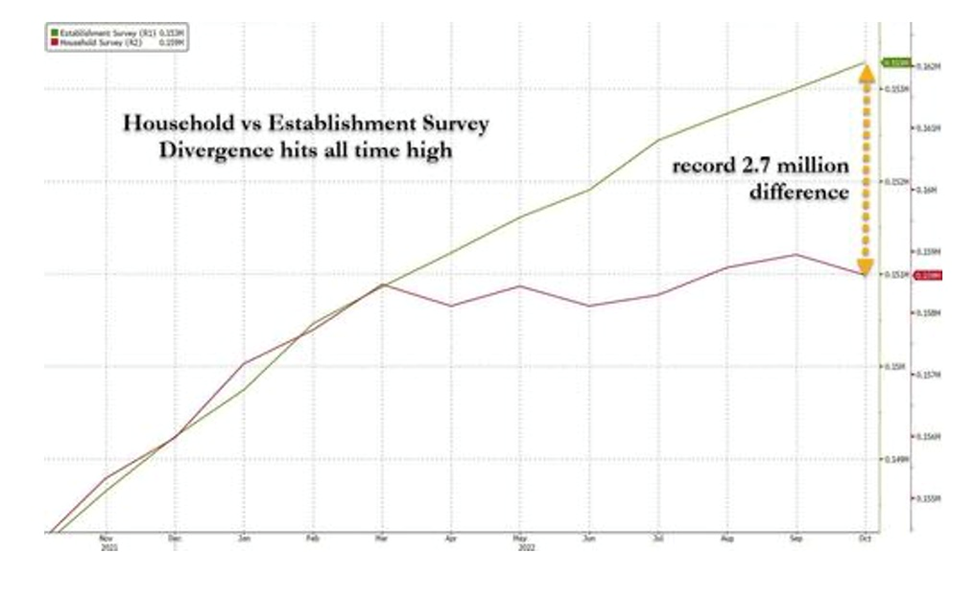

Then there is the wide gap between the closely watched Establishment Survey of jobs data, and the more accurate if volatile Household Survey, the two core components on which the monthly non-farm payrolls report is based.

Zero Hedge first reported on the divergence in early July, when we found that the gap between the Housing and Establishment Surveys had blown out to 1.5 million starting in March when “something snapped.”…

Since then the difference only got worse, and culminated earlier this month when the gap between the Establishment and Household surveys for the November dataset nearly doubled to a whopping 2.7 million jobs.

[A]ccording to the Household Survey, just 12,000 jobs were created since March, while according to the Establishment Survey – which moves markets and sets Fed policy – the increase in jobs over the same period was 2.692 million!

How to account for the huge difference? Well, the Bureau of Labor Statistics each month tabulates the number of jobs created across the country, but to do this monthly means sacrificing accuracy. Much more comprehensive and accurate figures are indicated in the BLS’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages report.

The upshot is that this job “overstating”, which was 1.5 million in June according to Zero Hedge, and 1.1 million as tabulated by the Philadelphia Fed, nearly doubled to 2.7 million from March to November.

The error is not trivial; its gravity is compounded by the fact that the Fed is basing its interest-rate decisions on jobs data that is incorrect. As Zero Hedge rightly points out,

[T]he Fed is shaping monetary policy using the clearly flawed assumption that the US labor market is “hot”, “tight” and “strong”, when in reality we now know that between March and June, monthly payrolls were overstated by about 350,000. This matters because this is what the BLS reported for payrolls for those months:

- April 368K

- May 386K

- June 293K

Now take those numbers and adjust them to subtract an average of 350K from each month (to get the revised Philly Fed payroll over this period) and you get this:

- April 18K

- May 36K

- June 57K

And visually.

Still think the Fed would be hiking 75bps this summer if instead of an average monthly job gain of 350K, Powell was seeing zero monthly payroll increases?

This isn’t the only wrong set of figures the Fed is relying on, to make the most important policy decision (interest rates) affecting US stock and bond markets, and millions of investors.

In an earlier article we pointed out the Fed’s go-to inflation gauge, core PCE, under-weights rent and over-weights health care. It also leaves out two of the most vital categories of household spending, food and energy/ gasoline. In November the core PCE was just 4.98%.

Why the Fed is wrong about inflation coming down

But according to the BLS’s latest Consumer Price Index Summary, the energy index increased 13.1% for the 12 months ending November, and the food index climbed 10.6% over the last year. Food at home and food away from home was a respective 10.6% and 12% more expensive, gasoline was up 10.1%, electricity prices gained 13.7%, and fuel oil was up a whopping 65.7%.

Do you see now why the core PCE doesn’t tell anything close to the real story? And even the CPI is misleading in that it’s an average of all categories, some of which may be rising in price dramatically.

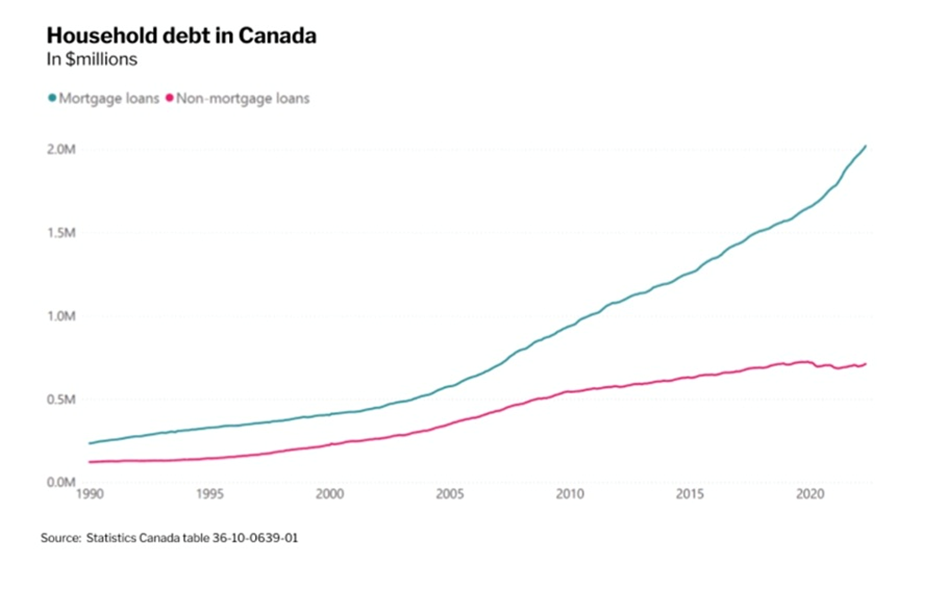

It appears all but certain the world economy will enter a recession within the next six to 12 months. The warnings are written in the inverted yield curve (an extremely reliable recession indicator), stagnant US manufacturing data, and a return to high debt levels among US and Canadian consumers, post-pandemic. The latter is a concern because it ups the risk of bankruptcies, delinquencies and forced stock selling, amid higher interest rates.

Visualizing (and Understanding) an Inverted Yield Curve

The 3-month/ 30-year and the 5-year/ 30-year segments of the yield curve are useful early indicators of a recession. Currently the 3mo30yr is still flattening and the 5y30y is still inverted, suggesting a recession is at least a few months away. (Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist, via Zero Hedge)

New research from the Bank of Canada found that variable-rate mortgages now account for one-third of outstanding mortgage debt, up from about one-fifth at the end of 2019 (Financial Post, Nov. 22, 2022). Moreover, about half of these mortgages have reached their trigger rate, which is the point where additional payments may be needed. This number represents about 13% of all Canadian mortgages.

In fact Canadian households are among the most indebted in the developed world. 2020 household debt in Canada was easily the highest of G7 countries, at 177.3% of disposable income, followed by the UK at 147%. Household debt in the US that year was 101%. Within the 38-member Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Canada ranks ninth in terms of average household debt. (Business Council of Alberta)

Inflation is the fourth horseman

Source: Business Council of Alberta

Hitting the wall of debt maturity

According to the Institute of International Finance (IIF), the global debt-to-GDP ratio will reach 352% by the end of 2022. (remember, the US debt to GDP ratio in 1982 was around 35%. Today it is more than three times higher, at 120%.)

The issuance of European and American high-yield bonds reached a record-high $1.6 trillion in 2021, according to the IMF. A lot of this debt is rolling over at much higher interest rates, pushing pressure on the governments who issued it to pay out the interest when the bonds mature. Daniel LaCalle in Mises.org states,

All of the risky debt accumulated over the past few years will need to be refinanced between 2023 and 2025, requiring the refinancing of over $10 trillion of the riskiest debt at much higher interest rates and with less liquidity.

Moody’s estimates that United States corporate debt maturities will total $785 billion in 2023 and $800 billion in 2024. This increases the maturities of the Federal government. The United States has $31 trillion in outstanding debt with a five-year average maturity, resulting in $5 trillion in refinancing needs during fiscal 2023 and a $2 trillion budget deficit…

If you think the problem in the United States is significant, the situation in the eurozone is even worse. Governments in the euro area are accustomed to negative nominal and real interest rates. The majority of the major European economies have issued negative-yielding debt over the past three years and must now refinance at significantly higher rates. France and Italy have longer average debt maturities than the United States, but their debt and growing structural deficits are also greater. Morgan Stanley estimates that, over the next two years, the major economies of the eurozone will require a total of $3 trillion in refinancing.

Lacalle also points out that the public was done a disservice by governments who claimed there was no inflation caused by almost uninterrupted monetary expansion (aka “QE”) since 2008 (despite massive home price and financial sector inflation).

In 2018 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) food index reached a record high, as did the housing, health, education and insurance indices. Lacalle writes,

The magnitude of the monetary insanity since 2008 is enormous, but the glut of 2020 was unprecedented…

In 2020-21, the annual increase in the US money supply (M2) was 27%, more than 2.5 times higher than the quantitative easing peak of 2009 and the highest level since 1960…

All of this unprecedented monetary excess during an economic shutdown was used to stimulate public spending, which continued after the economy reopened… And inflation skyrocketed. However, according to [European Central Bank President Christine] Lagarde, inflation appeared “out of nowhere.”

Xi of Arabia

For the first five months of this year, China’s Treasury holdings fell below $1 trillion, a 12-year low, with concerns about the risk of Russia-style sanctions accelerating a financial decoupling driven by political tensions, according to Nikkei Asia. The country sold US government debt for a seventh straight month in June, signaling that Beijing is trying to defend the yuan against the dollar, added Markets Insider.

Now it appears the United States dollar is facing another threat from China, a Saudi Arabia-centered “petroyuan” to compete against the petrodollar established in the early 1970s by President Richard Nixon.

Recognizing that the US, and the rest of the world was going to need a lot of oil, and that Saudi Arabia wanted to sell the world’s largest economy more crude, Nixon and Saudi Arabia came to an agreement in 1973 whereby Saudi oil could only be purchased in US dollars. This caused an immediate and strong global demand for the buck.

While nearly 80% of the world’s oil continues to be priced in dollars, that may be changing, as governments at odds with the United States, mostly China and Russia but also Iran, Venezuela and, ironically, Saudi Arabia, look to do business in currencies other than the USD.

About a week ago Chinese President Xi Jinping flew to Riyadh and announced that From now on, China will use the yuan for oil trade, through the Shanghai Petroleum and National Gas Exchange, and invited the Persian Gulf monarchies to get on board.(The Cradle.co, Dec. 16, 2022)

Nixon must be turning in his grave. But at the time, he couldn’t have foreseen the economic tour de force the Middle Kingdom would become. China has been the largest importer of crude for five years now, with half coming from the Arabian peninsula and more than a quarter sourced from Saudi Arabia.

But it isn’t just oil sales that the Saudis and the Chinese have agreed upon. According to The Cradle columnist Pepe Escobar, Over $30 billion in trade deals were duly signed [with wider Arabia] – quite a few significantly connected to China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects.

China and Iran, for example, in 2021 clinched a 25-year partnership deal worth a potential $400 billion in investments.

More importantly, writes Escobar, The nine permanent SCO [Shanghai Cooperation Council] members now represent 40 percent of the world’s population. One of their key decisions in Samarkand was to increase bilateral trade, and overall trade, in their own currencies.

The importance of this cannot be underestimated: 40% of the world’s population is no longer interested in conducting trade using US dollars!

Also of concern, regarding the US dollar’s continued status as the world’s reserve currency, Escobar quotes Vladimir Putin stating, “The work has accelerated in the transition to national currencies in mutual settlements… The process of creating a common payment infrastructure and integrating national systems for the transmission of financial information has begun.”…

Russia since 2014 has been improving its SPFS payment system, in parallel with China’s CIPS, both bypassing the western-led SWIFT…

[T]he drive towards the petroyuan proceeding [is] in parallel to the drive towards a “common paying infrastructure” and most of all, a new alternative currency bypassing the US dollar.

Conclusion

In our three-part series on ‘The Debt Trap’, we showed how out-of-control debt has become a millstone around the necks of some of the world’s largest economies.

Global debt more than doubled from US$116 trillion in 2007 to $244 trillion in 2019. It now sits at $281 trillion.

The United States is the undisputed champion of unsustainable IOUs; the country now has a national debt of $31.4 trillion.

There is a clear link between a rising debt to GDP ratio and gold prices. In October 2020 the US ratio surpassed 100% for the first time since the Second World War; it now sits at 120%, not much lower than Italy’s 155%. Italy has long been considered a debt-ridden basket case of an economy, incomparable to the United States backed by the mighty greenback. Yet some commentators are beginning to see the United States heading down the same financial road to ruin.

There are historical examples of hyperinflation (Germany, Zimbabwe, Venezuela) and banking crises (Argentina, Ireland) whereby citizens lost faith in their money. Trust in the US government is at all-time low; only 25% of the population has any faith in fat-cat Washington politicians.

Forty-year-high inflation is eroding the purchasing power of fiat currencies, not just the US dollar but the British pound, the euro, the Canadian dollar, etc., because it takes more units of currency to buy the same amount of goods as before).

Owning gold (and silver) continues to be the best defense against inflation, stagflation, and rampant currency debasement, during this period of unprecedented and irresponsible debt accumulation.

The dollar has lost 90% of its purchasing power since 1950.

By contrast, since 1972 gold has gone from $35/oz to $1,820.

There is no better validation of gold as a solid investment vehicle, than current central bank buying.

For centuries, central banks around the world have not only been keeping foreign currencies, but also gold, in their reserves for diversification purposes.

Today, central banks hold more than 35,000 metric tons, which equates to about a fifth of all the gold ever mined. This is also the largest amount of gold maintained in global reserves since 1990.

The leading gold holders are some of the world’s most powerful nations, such as the US, Germany, Italy and France, all of which are keeping 60% of their reserves as gold. This is a testament to the significance of gold in the central banking system.

According to the World Gold Council, central banks globally added another 31 tons of gold to official reserves in October, putting central bank holdings at their highest level since 1974.

These numbers reflect officially reported gold purchases but there were also large unofficial buys in the third quarter. According to Schiffgold.com, China was likely the mystery buyer stockpiling gold to try to minimize exposure to the US dollar.

The third-quarter figures were equally impressive. Another Schiff Gold article states that central banks added nearly 400 tons in Q3, 300% more than the year-ago quarter, and the largest quarterly increase in central bank gold reserves since the World Gold Council started keeping records in 2000. 2021 was the 12th consecutive year of net purchases, with central banks over that time buying a total of 5,783 tonnes. This equates to nearly two years worth of global gold mine production, at the current annual rate of 3,000 tonnes (US Geological Survey).

If central banks are buying gold at such volumes, right now, there’s got to be a reason. Could it be that they think it’s going up? Well yes but they are not buying gold as a trade How about a Debt Jubilee?

Taking into consideration our ‘4 pillars’ mentioned at the start of this article I see the Fed reducing its rate hikes to .25 basis points before the end of the first quarter 2023 and pausing by the middle of the year. A reversal could follow shortly after.

That means a weakening US$ and a rising gold/ silver price environment. Historically the greatest leverage to an increasing precious metal price is a quality junior. Also, for several metals like copper, nickel and graphite, the green revolution is demanding more metal than can be supplied, and junior companies own the world’s future mines, making them extremely attractive take-over targets.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Song by Samantha Fish – Lay It Down

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.