Where are we in the debt cycle? – Richard Mills

2023.09.20

The debt cycle is something many North Americans have become all too familiar with.

These days, it is common for homeowners to take out mortgages in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, creating pressure to make the hefty monthly payments. When mortgage rates climb, as they have done recently, those holding variable-rate mortgages can suddenly find themselves on the hook for hundreds a month more. Fixed-rate mortgage holders face a similar nasty surprise when forced to renew at a higher rate.

Mortgages, car loans, student loans and lines of credit are all tied to the interest rate set by the Bank of Canada, or the Federal Reserve in the United States.

While taking on short-term debt can be a useful investment in the future, it needs to be paid off to build net worth. Failure to do so can result in a debt cycle from which escape is all but impossible.

Those in lower-income brackets endure the double-whammy of the skyrocketing cost of borrowing, and high inflation, which reduces their purchasing power over essentials like groceries and gas. The average credit card now charges 20% interest. Payday loan companies demanding usurious interest rates are a last-ditch resort for some.

According to The Balance, A debt cycle is continual borrowing that leads to increased debt, increasing costs, and eventual default. When you spend more than you bring in, you go into debt. At some point, the interest costs become a significant monthly expense, and your debt increases even more quickly. You might even take out loans to pay off existing loans or just to keep up with your required minimum payments.

The concept can also be transposed to a macroeconomic level.

Investopedia defines the credit cycle as the phases of access to credit by borrowers based on economic expansion and contraction. It is one of the major economic cycles in a modern economy, and the cycle length tends to be longer than the business cycle because of the time required for weakened fundamentals of a business to show up.

Regarding the latter, this makes sense in that there is always a lag between the effects of rising or falling interest rates on businesses, which normally see profits increase during low-interest-rate credit cycles, and decrease when the cost of borrowing goes up during high-interest rate cycles.

Business cycles are comprised of cyclical upswings or downswings based on broad measures of economic activity — output, employment, income and sales. Upswings are known as expansions and downswings are called recessions.

According to Investopedia,

Credit cycles first go through periods in which funds are relatively easy to borrow. This expansionary period is characterized by lower interest rates, lowered lending requirements, and an increase in the amount of available credit, which stimulates a general increase in economic activity. These periods are followed by a contraction in the availability of funds.

During the contraction period of the credit cycle, interest rates climb and lending rules become more strict, meaning that less credit is available for business loans, home loans, and other personal loans. The contraction period continues until risks are reduced for the lending institutions, at which point the cycle troughs out and then begins again with renewed credit.

A contraction in credit is considered to have been a primary cause of the 2008 financial crisis.

More information regarding the relationship between the credit cycle and the business cycle comes via Wikipedia, which states that some economists including Barry Eichengreen and Hyman Minsky, regard credit cycles as the fundamental process driving the business cycle.

Other economists say the credit cycle alone cannot explain the business cycle, with other multipliers being important, such as changes in national savings rates and fiscal/ monetary policy.

According to Wikipedia,

During an expansion of credit, asset prices are bid up by those with access to leveraged capital. This asset price inflation can then cause an unsustainable speculative price “bubble” to develop. The upswing in new money creation also increases the money supply for real goods and services, thereby stimulating economic activity and fostering growth in national income and employment.

When buyers’ funds are exhausted, an asset price decline can occur in the markets which had benefited from the credit expansion. This can then cause insolvency, bankruptcy, and foreclosure for those borrowers who came late to that market. This, in turn, can threaten the solvency and profitability of the banking system itself, resulting in a general contraction of credit as lenders attempt to protect themselves from losses.

Billionaire investor Ray Dalio counts the credit cycle, the debt cycle, the wealth gap cycle and the global geopolitical cycle among the factors that drive worldwide shifts in wealth and power.

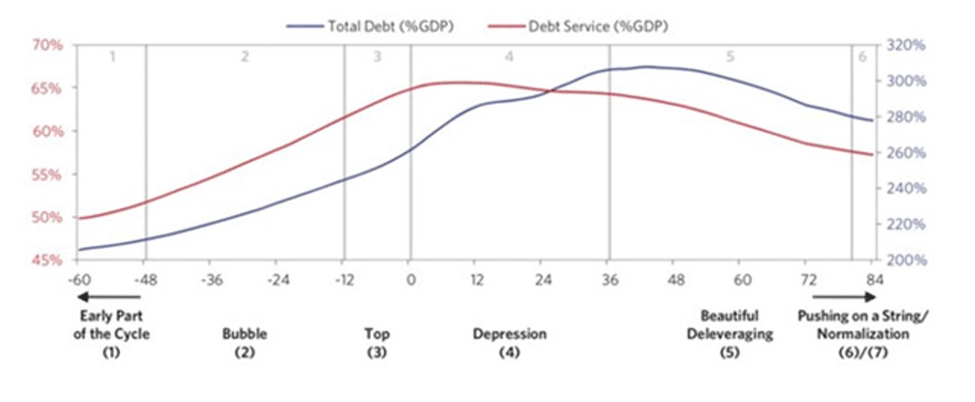

In his book, ‘Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises’, Dalio suggests that debt is inherently cycle and that each debt cycle goes through six stages. These stages are described and graphed below, via Seeking Alpha:

Stage 1 is the “good” part. People borrow money, but not too much. They use it for productive purposes. This helps the economy grow and lifts asset prices. And that’s where things start going south.

In Stage 2, which Dalio terms the “Bubble,” people look at the recent past and decide asset prices, total demand, and consumption will keep going up. They overconfidently borrow more money and start having too much leverage.

Stage 3, the “Top,” occurs when central banks, regulators, and sometimes even the lending institutions notice problems. They take measures: raise interest rates, tighten lending standards, and so on.

Stage 4, the “Depression,” happens when growth slows or reverses beyond the ability of monetary and political authorities to help. Yet they keep trying. This is when we see interest rates go to zero or negative. The central bankers are out of bullets at this point. Everyone just has to suffer.

Stage 5 is the deleveraging phase. It is when businesses and families reduce spending to pay down debt and reduce their leverage. It can last a long time. But as leverage falls, people get a handle on their debt service costs and slowly start to recover.

Eventually, the economy reaches Stage 6, normalization, and the cycle repeats.

The obvious next question is where are we in the current debt cycle?

The six Dalio stages appear to indicate we are in Stage 3, when central banks raise interest rates and tighten lending standards. We are not yet in Stage 4, Depression, when growth slows beyond the ability of monetary authorities to help — although if the economy were to plunge into recession, this could easily happen.

As proof of Stage 3, consider: The Federal Reserve has hiked rates 11 times since March, 2022, putting its key interest rate within a range of 5.25%-5.5%, the highest level in more than 22 years.

A Fed survey in July showed US banks reporting tighter credit and weaker loan demand.

“The most cited reasons for expecting to tighten lending standards were a less favorable or more uncertain economic outlook, an expected deterioration in collateral values, and an expected deterioration in credit quality of CRE (commercial real estate) and other loans,” the Fed said via Reuters.

The Seeking Alpha article notes there have been two occasions in the past century when the United States went through debt crises so severe that the Fed had to drop rates to zero and resort to unconventional policies like quantitative easing. The first was in the 1930s and the second was in 2008-09, when the Fed launched four rounds of QE. Both worked in the sense that asset prices recovered.

Signs of trouble

Dalio made headlines in June when, speaking at the Bloomberg Invest conference in New York, he warned the US economy is facing a “risky situation” due to the fact that there may not be enough buyers for an influx of government debt on the market. He was referring to the expectation that the US Treasury will issue $1 trillion worth of Treasury bills by the end of this year, as the government looks to build its cash reserves following a last-minute deal to raise the debt ceiling.

“In my opinion, we are at the beginning of a very classic late, big-cycle debt crisis when you are producing too much debt and have also a shortage of buyers,” Dalio told Bloomerg’s David Westin.

The hedge fund founder believes the Fed will be forced to maintain high interest rates to attract buyers to those Treasuries, causing strains in the US economy.

“The consequences of that are going to be a weaker economy going forward,” he said. “It doesn’t have to be a big downturn because of the household sector, but it is a balance sheet kind of recession. I think things are going to get worse in the economy; there’s a financial issue at the same time as you have this internal conflict, so I think that’s going to make for a risky situation.”

Dalio is in good company with his prediction of a hard landing when it comes to the expected outcome of the Fed’s tight-money policy, as the central bank tries to balance the lowering of inflation with higher interest rates that are bringing hardship to borrowers.

Earlier this year, renowned economist Nouriel Roubini re-published his 2008 commentary in which he warned that the 2006-07 US housing bust would lead to a severe US and global financial crisis. “Fifteen years later,” he told Project Syndicate, “we may once again be on the verge of a twin economic and financial crisis – only this time the outcome could be even worse. After all, private and public debt-to-GDP ratios are much higher today, and the past few years have laid bare the costs and limitations of unconventional monetary, fiscal, and credit policies.

“Moreover, back in early 2008, inflation was falling and leading to deflation, and a demand shock and a credit crunch allowed for unconventional policy easing on a massive scale. Today, negative supply shocks have caused inflation to surge, forcing central banks to tighten monetary and credit policies even as many economies have been heading toward recession.”

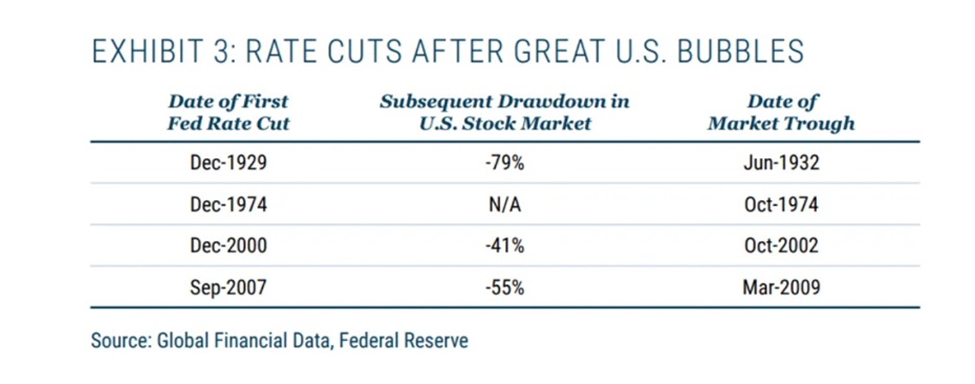

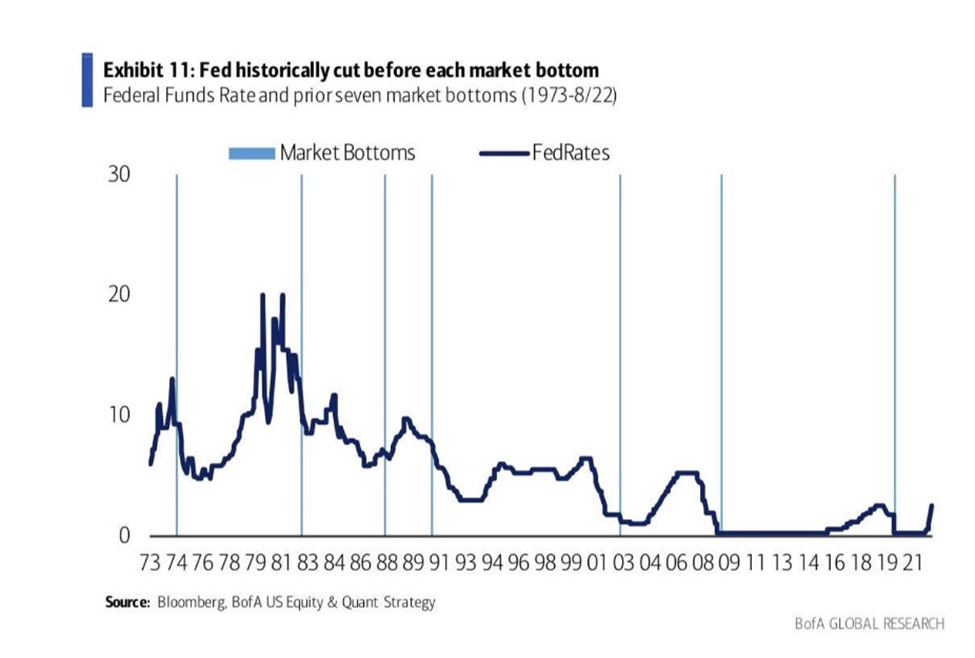

As for the so-called “Fed pivot” to lowering interest rates, one commentator believes that rate cuts do not necessarily mean the market will move higher, citing historical precedent.

In a September column, Quoth the Raven published a table indicating that market bottoms generally follow rate cuts. For example in September 2007, the first rate reduction resulted in a 55% drawdown in the US stock market that continued until March 2009, the market trough. Similar patterns occurred in 1929 and 2000.

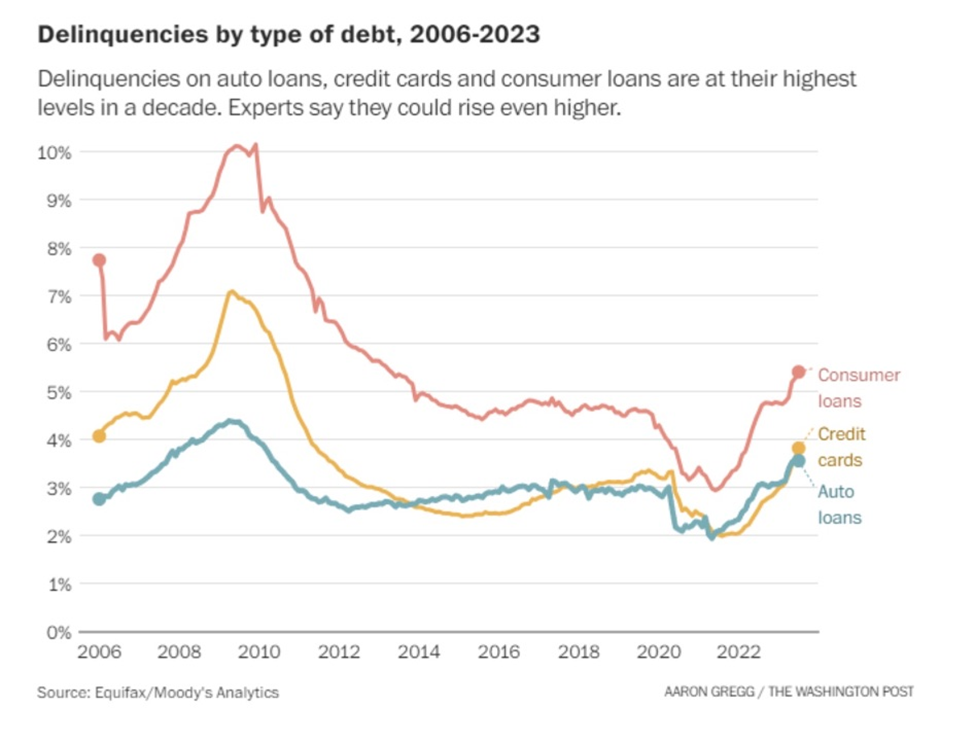

Rate cuts aren’t the only signal the market could be ready to tank. In the next chart, Quoth the Raven proves that delinquencies — on auto loans, credit cards and consumer loans — are at their highest in a decade. On the decline since 2008, delinquencies on all three types of debt are now seen curling upward.

What effect do delinquencies have on the economy? QTR describes the cycle in a nutshell:

Debt delinquencies indicate borrowers are unable to meet their obligations. Most immediately, financial institutions that have issued these debts may experience liquidity constraints, as their expected flow of income is interrupted. In an environment of rising delinquencies, it’s natural for lenders to become more cautious, tightening lending criteria or increasing interest rates to offset the higher risk. This might not only inhibit entrepreneurship but also decrease consumer spending, as both individuals and businesses find it harder to obtain credit.

When consumers spend less, businesses see reduced revenue and profits, making them less attractive investments. Lower earnings can then lead to a decline in stock prices (via multiples or fundamentals or both).

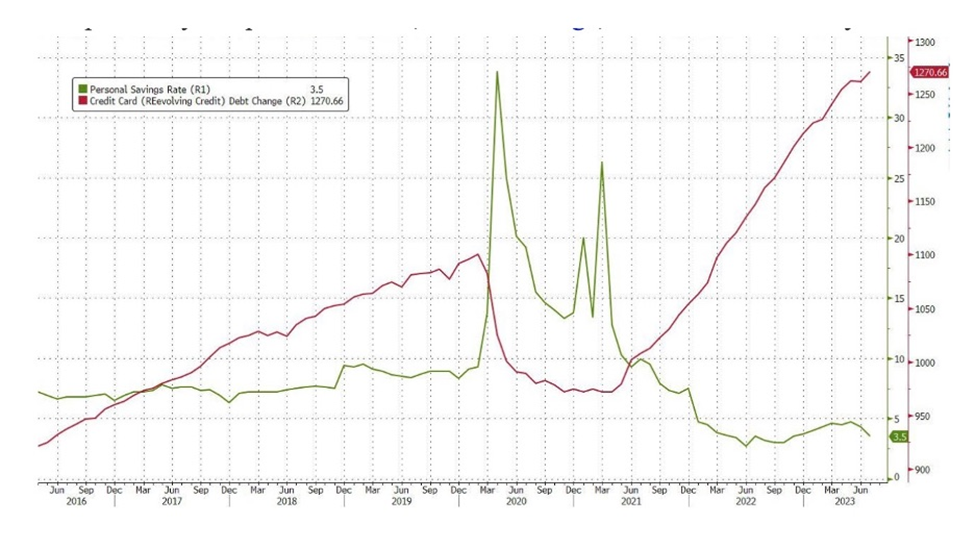

The third chart, via Zero Hedge, shows the personal saving rate and credit card debts reaching “an alarming divergence” compared to years past (the green line versus the red).

Note the spike in personal savings during the early 2020s, the onset of the pandemic and the stimulus programs that followed, compared to the much lower level now. Following the opposite trend, credit card debt in 2021 was significantly less than today.

Americans are definitely becoming more dependent on their plastic for making ends meet. According to The Economic Collapse blog, there are currently eight signs we are on the verge of a major credit card debt crisis (edited for brevity):

#1 The total amount of credit card debt in the United States has surpassed the one trillion dollar mark and is now at the highest level ever recorded.

#2 The average rate of interest on credit card balances has now risen to a new all-time record high of 20.63%.

#3 A whopping 47% of all U.S. cardholders are now carrying balances from month to month.

#4 The average credit card debt level in the United States just continues to grow. The national average credit card debt grew to $7,227, according to the survey.

#5 Most Americans are not running up credit card debt because they are making frivolous purchases. According to one industry insider, most Americans are doing it

#6 The number of credit card delinquencies in the U.S. has surged dramatically over the past two years.

#7 One recent survey discovered that many Americans that actually use personal loans to consolidate credit card debt end up quickly running up new credit card balances close to their previous levels.

#8 At a time when economic conditions are slowing down all over the nation, Americans are becoming increasingly dependent on their credit cards.

America’s debt problem

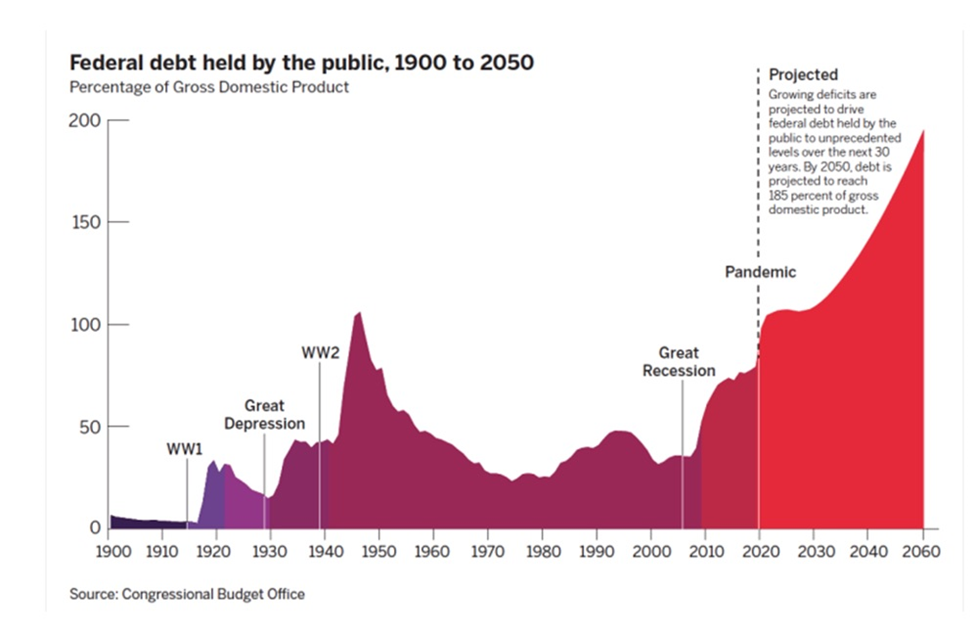

The US has a serious debt problem. Its gross national debt sits just below $33 trillion, or 122% of GDP. The bigger problem, though, is the pace at which the debt is accumulating, leading to ballooning interest payments.

(In fact the issue is global. The Institute of International Finance (IIF) says global debt hit a record $307 trillion in Q2, despite higher interest rates curbing bank credit. More than 80% of the latest debt buildup had come from the developed world, with the US, Japan, Britain and France registering the largest increases. (Reuters, Sept. 19, 2023))

America’s debt problem is only getting bigger

According to Congressional Budget Office projections, interest payments will total around $71 trillion over the next 30 years and will take up 35% of federal revenues by 2053. Interest costs would also become the largest “program” over the next few decades, it predicted.

In June, the CBO projected that annual net interest costs would total $663 billion in 2023 and almost double over the coming decade, soaring from $745 billion in 2024 to $1.4 trillion in 2033 and reaching $10.6 trillion over that period.

If inflation is higher than its projections, and if the Fed raises interest rates by larger amounts than the agency projected, such costs would rise even faster than anticipated.

Over the past decade, the US national debt has nearly doubled, including a period between 2020 and 2023 when federal spending amounted to a jaw-dropping $28 trillion.

In June, a bipartisan agreement to suspend the debt ceiling was reached, which essentially gave the US government a free rein on its spending. Weeks after that, its debt, to no one’s surprise, crossed the newly extended $31.4 trillion ceiling and reached the $32 trillion mark for the first time.

The debt is on track to top $50 trillion by the end of the decade, even after some of the spending cuts in the debt ceiling deal are taken into account. Even this projection seems conservative, given the debt has already risen by over $1 trillion in the two months since that agreement.

The CBO projects that the US government will run trillion-dollar deficits over the next 10 years, resulting in a cumulative deficit of $20.3 trillion between 2024 and 2033.

Lawrence McDonald, editor of ‘The Bear Traps Report’, opined in a recent blog post that fiscal spending, especially since the pandemic, has created a “mind-blowing hole” in the nation’s finances.

“The US government has already spent $5.3 TRILLION this year. We are on track for the 4th consecutive year with $6 trillion or more in government spending. Since 2020, the US government has spent a jaw-dropping $25 TRILLION. To put this in perspective, the market cap of the S&P 500 is $37 trillion. Spending since 2020 is equivalent to 68% of the entire S&P 500 market cap,” he wrote.

Can high rates be sustained?

In the short term, Wall Street is convinced the Fed will need to keep rates higher than expected given recent economic performance. But over a longer horizon, there’s a debate on whether high rates can be sustained, especially if the fiscal spending problem gets worse.

One former Fed official argued that in the long run America may require higher rates to balance the need for more borrowing (implied by higher government deficits).

However, it would also make perfect sense for the Fed to hold rates low, because, according to former US presidential candidate Ron Paul, that’s exactly what the government is counting on to keep up its spending, because spending limits aren’t ever going to work.

In 2024, Paul believes the Fed will likely pause its rate increase in the hope of boosting economic activity to help President Biden’s re-election campaign. But after that, it would have to find a way to keep both rates and inflation low enough to satisfy everybody.

Lance Roberts, chief portfolio strategist/economist for RIA Advisors, also sees the Fed lowering rates due to the “inability of the economy to sustain higher rates due to mounting debt issuance and rising deficits.”

In fact the Fed is seeing the impact of high interest rates reflected in its own bottom line. This week, central bank data showed Federal Reserve losses breached the $100-billion mark for the first time. That’s because the Fed is paying out more in interest costs than it takes in from the interest it earns on bonds it owns. Some observers quoted by Reuters said the losses could eventually double before abating.

Conclusion

I am sticking to my prediction of a soft landing with no recession — meaning the Fed successfully eases price pressures through higher interest rates without causing the economy to contract.

Cleary I am not going out on a limb here. As Bloomberg wrote recently, with inflation falling and economic output growing, economists inside and outside the Fed are increasingly betting that policymakers might pull off [a soft landing] this time.

US gross domestic product has been increasing steadily since the rate hikes began, and employment is strong, with the jobless rate hovering around lows last seen in the late 1960s. The US economy grew at 2.1% in the second quarter.

The US Treasury Secretary unsurprisingly backs a soft landing, telling Reuters that such a scenario can withstand near-term risks including a

United Auto Workers strike, a government shutdown threat, a resumption of student loan payments and spillovers from China’s economic woes.

[Janet] Yellen said on Monday that she sees evidence that the economy is keeping to a path of making substantial progress to reduce inflation while maintaining a strong labor market and healthy consumer spending.

More analytically, recession avoidance could win the day, considering that one of Dalio’s pre-conditions for us being in a “debt crisis” — a shortage of US Treasury buyers — has yet to transpire.

Bloomberg reported that sales of short-term US government paper increased every day of the first week of August. In fact the news outlet said Treasury bill demand is so strong, it is crowding out money-market mutual funds.

The US government is currently on the hook to investors for than $25 trillion, another Bloomberg story said, as it ramps up borrowing to plug a widening budget gap. The article notes that the record $25T total debt outstanding is expanding in part because higher interest rates have inflated the cost of servicing the existing debt. Also, the outlook for the federal budget deficit has worsened.

While there are concerns about China wanting to reduce its exposure to US debt, and Saudi Arabia selling Treasuries, data quoted by Reuters show that central banks’ holdings of Treasury securities have rebounded from October’s 10-year low, and buying this year is on track to top last year’s chunky $183 billion.

Indeed, foreign central bank purchases in the two and a half years through June this year come to $283.5 billion, according to Reuters calculations based on adjusted figures from Fed economists Carol Bertaut and Ruth Judson.

That’s well over quarter of a trillion dollars, a large amount in anyone’s book.

And let’s not forget Saudi Arabia and the US just announced they are working towards a new defense partnership much like the one the US has with both Japan and South Korea.

The bottom line? Although there are valid concerns about the size of US debt, the rise in loan delinquencies, and the potential for getting caught up in a debt cycle from which there is no escape, a descent into Ray Dalio’s Stage 4 Depression is not a foregone conclusion, especially if the Fed succeeds in engineering a no-recession soft landing.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.