What if we threw a Cold War and nobody came?

2019.03.26

Russia just can’t seem to keep itself from stepping on America’s toes – the foot belonging to Latin American countries that are within the American sphere of influence known historically as the Monroe Doctrine.

On Sunday two Russian military planes reportedly landed in Caracas carrying a Russian defense official and nearly 100 troops – in another demonstration of the close ties between Russia and Venezuela.

Three months earlier, the two nations held joint military exercises, in an apparent nose-thumbing directed at opponents of embattled President Nicolas Maduro, particularly the United States.

Further north, the Russian air force is flying into territory it’s not supposed to be entering. At the end of January US Air Force and Canadian fighter jets were scrambled to escort two Russian bombers that were traveling over the North American coastline, in an area patrolled by the Royal Canadian Air Force.

In 2018 NORAD (the North American Aerospace Defense Command) reported two incidents of Russian bombers that were spotted and intercepted near the coast of Alaska.

Russian Tu-160 Blackjack bomber

Meanwhile the United States has said it would withdraw from the INF Treaty unless Russia ends what the US says are violations of the landmark 1987 arms control agreement (ie. that Russia has begun R&D on a conventional intermediate range missile), due to expire in August.

Not being party to the INF Treaty will allow the United States to counter Russian aggression in Eastern Europe – the latest example being a major training mission being carried out in Crimea. The Kyiv Post reports up to 1,500 Russian airborne paratroopers, plus combat helicopters, military transport planes and landing craft from the Black Sea Fleet, have been deployed to Russian-occupied Crimea to drill major offensive operations.

If the US is no longer tied to a treaty that prohibits intermediate-range nuclear and conventional missiles, the military will also have a freer hand in the South China Sea.

Tensions in that part of the world continue to be high. On Sunday the US Navy increased the frequency of vessel movement through the Taiwan Strait, after Beijing sent military aircraft and ships to circle the island for drills, Foreign Affairs reported. President Xi Jinping has warned that any attempt by Taiwan, or its US ally, to assert Taiwan’s independence will be met with armed force.

Finally, late last year in the South China Sea – a highly strategic and economic waterway that China claims as its own – a Chinese warship came dangerously close, within 45 yards, of the bow of a Navy destroyer.

These incidents are mentioned to show evidence of ever-increasing aggression and militarization among the three largest military powers in the world right now: the US, China and Russia. We’ve written about this before, in the context of rare earths – see Rare earths in the context of new arms race and Pentagon missile-making plan is perplexing.

This article will present a scenario of what could happen if there is another buildup of conventional and nuclear weaponry, similar to the “Cold War” that gripped Russia and the US between 1957 (the launch of Sputnik) and 1989 (the fall of the Iron Curtain). How would China, Russia and the US fare, in terms of getting enough critical minerals to supply their own militaries?

The materials of war

To answer this question we need to start with the list of 23 minerals the US Geological Survey identified in 2017 as being critical to US national security and the economy.

The US is dependent on China for 20 of those 23 minerals. Along with rare earths, China is the dominant supplier of antimony, indium, tellurium and tungsten.

An expanded list of 35 minerals was published by the Department of the Interior alongside an Executive Order by President Trump, for the Commerce Department to come up with a strategy by this August, for America to reduce its reliance on critical minerals.

From the list we can identify a number of minerals that have military applications. Remember the US Military depends on imports for all of these materials:

- Aluminum (bauxite) is used in the Humvee (HMMWV), HEMTT and Bradley Fighting Vehicle, and armored plates to resist explosives. The airframe of the F-16 is 80% aluminum. Aluminum is mixed with other elements, including silicon, magnesium, copper, to create high-strength alloys. The US is 100% reliant on imports of metallurgical grade bauxite.

- Antimony is used in batteries and flame retardants.

- Beryllium is used as an alloying agent in aerospace and defense industries.

- Chromium is used primarily in stainless steel and other alloys used in rechargeable batteries and superalloys.

- Gallium is used for integrated circuits and optical devices like LEDs.

- Germanium is used for fiber optics and night vision applications.

- Indium is mostly used in LCD screens.

- Lithium is used primarily for batteries.

- Manganese is necessary for steelmaking. Steel cannot be manufactured without adding 10 to 20 pounds of manganese per ton of iron.

- Niobium is used mostly in steel alloys.

- Rare earth elements are primarily used in batteries and electronics.

- Rhenium is used for lead-free gasoline and superalloys.

- Rubidium is used for research and development in electronics.

- Scandium is used for alloys and fuel cells.

- Tantalum is used in electronic components, mostly capacitors.

- Tellurium is used in steelmaking and solar cells.

- Tin is used as protective coatings and alloys for steel.

- Titanium. Due to its ability to withstand high temperatures, high tensile strength and corrosion resistance, titanium alloys are used in aircraft, armor plating, navy ships and missiles. About two-thirds of titanium is used in aircraft engines and frames.

- Tungsten is primarily used to make wear-resistant metals.

- Vanadium is used for titanium alloys.

Rare earths are central to the whole spectrum of defense technologies that are vital to every military. Without them, countries would be unable to produce much of the military hardware and equipment required for national defense. Moreover, switching from current suppliers (ie. China) would cause major disruptions to supply chains. According to the US Government Accountability Office, it would take 15 years to overhaul the defence supply chain, meaning any changes to it need considerable lead time.

Among the military applications of rare earth elements are:

- Radar and sonar used to prevent collisions, for surveillance and navigational aids. The Patriot Missile Air Defense System employs radio frequency circulators to magnetically control the flow of electronic signals in the radar and missiles. Rare earths required: gadolinium, samarium, yttrium.

- Communications and displays required by soldiers, sailors and airmen to see analog and digital data. Examples are lasers that help line-of-sight communication links in satellite and ground-based systems; old and new computer monitors; and avionics terminals. Rare earths required: dysprosium, erbium, europium, neodymium, praseodymium, terbium and yttrium.

- Lasers employed on vehicle-mounted systems like tanks and armored vehicles. They can identify enemy targets up to 22 miles.

- Precision-guided munitions (PGMs) take in a number of missile classes including cruise, anti-ship (ASM) and surface-to-air (SAM), as well as bunker busters. The heat-seeking AIM-9 Sidewinder missile has four fins on its fuselage that use rare-earth magnets to control its flight trajectory.

- Guidance and control systems that steer missiles and bombs towards their targets. Rare earths required: terbium, dysprosium, samarium, praseodymium and neodymium.

- Electronic warfare refers to a range of equipment that includes high-capacity power sources, storage batteries and electronic jamming devices. Rare earths required: yttrium-iron-garnet.

- Electric motors that require permanent magnets, of which the US Military is an important buyer. New equipment requiring powerful permanent magnets in the next generation of electric motors will include the US Navy’s Zumwalt DDG 1000 guided military destroyer, hub-mounted electric traction drives and integrated starter generators. Rare earths required: terbium, dysprosium, samarium, praseodymium and neodymium.

- Jet engines. The rare earth element erbium is added to vanadium to make it more malleable for use in vanadium-infused steel that goes into jet engines. While not specifically a rare earth element, the rare element rhenium is alloyed with molybdenum and tungsten. The F-22 Raptor and the F-35 Lightning II stealth fighter reportedly use 6% rhenium in their engines. The electrical systems in aircraft employ samarium-cobalt permanent magnets to generate power.

According to DefenseMediaNetwork, “The laser-equipped computer main gun sight on the Abrams M1A/2 tank combines a Raytheon rangefinder and integrated designator targeting system used to obtain a high-probability first hit.” Rare earths required: europium, neodymium, terbium and yttrium.

Rare earths required: dysprosium, neodymium, praseodymium, samarium and terbium.

According to The Hill, the US Department of Defense uses 750,000 tons of minerals a year.

Buying from our enemies

Yet as mentioned, the United States is completely dependent on China for 20 out of 23 critical minerals, many of which are needed for national defense. While the US has deposits of manganese and vanadium, for example, none are currently in production. The number of electric vehicles used by the military is going to grow rapidly, yet the United States has only one lithium mine that has been going since the 1960s and is being depleted. There is also only one American rare earth mine, Mountain Pass in California. It was sold to a US consortium including a Chinese company that is processing the rare earth concentrate into oxides, in China.

Without rare earths mined and processed in China, America would be unable to manufacture military hardware. Rare earths are great multipliers, they are used in making everything from computer monitors and permanent magnets to lasers, guidance control systems and jet engines. In most cases there are no substitutes and Australia is the only significant producer outside of China (non-Chinese sources only account for about 20% of rare earth mines).

Materials made from Chinese REEs are appearing in US fighter jets and rockets.

The $392-billion F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter program was close to being canceled about seven years ago but for intervention by the Pentagon to prevent further delays. Reuters reported in 2014 that the chief US arms buyer allowed two F-35 suppliers, Northrop Grumman Corp and Honeywell, to use Chinese magnets for the plane’s radar system, landing gears and other hardware.

In doing so, the Pentagon was actually waiving laws banning Chinese-built components on US weapons. Permanent magnets employ the rare earths neodymium, praseodymium and dysprosium.

As we reported earlier this year, through a program called the United Launch Alliance, US rockets are powered by Russian engines. Our Cold War enemy for 30-odd years, which ironically started the space race with the 1957 launch of Sputnik, all use RD-180 engines made by NPO Energomash, a Russian state-owned company.

Atlas Rocket

If Cold War Presidents from Harry Truman to Ronald Reagan knew that the nation’s national defense rested on technologies coming from its former and current adversaries, they would surely be turning in their graves.

How can a country be responsible for its own defense and projecting military force abroad, when it has to rely on its enemies to make its own weapons?

It’s globalism

How did we get here? The blame is largely shouldered by globalism. It used to be that countries were responsible for their own defense materials. The idea of your adversary selling you supplies for weaponry was ludicrous. There was a time when the United States controlled global rare earths production, through the Mountain Pass mine in California. In the late 1990s the US ceded control of Magnequench, a unit of General Motors that was producing permanent magnets, to the Chinese. Within a decade China had a monopoly on the rare earths market.

After World War II the United States created the National Defense Stockpile (NDS) to acquire and store critical strategic materials for national defense purposes. The NDS was intended for all essential civilian and military uses in times of emergencies. In 1992, Congress directed that the bulk of these stored commodities be sold.

Since then, a variety of factors I’ve covered before, including restrictive environmental regulations and a sharp decline in US mining investment, has made the United States dependent on foreign mines for a number of strategic metals – a situation I have dubbed A Nation’s Metallurgical Achilles Heel.

While many believe that world wars are consigned to the dust bin of history, a deeper reading shows that the Founding Fathers of the United States of America were focused squarely on the importance of maintaining a ready supply of materials necessary for the defense of the nation and war-making capabilities.

In the 1780s the US knew what it needed for war. When President George Washington signed the Tariff Act of 1789, he told Congress, “A free people … should promote such manufactures as tend to make them independent on others for essential, particularly military supplies.” Alexander Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures, written in 1791, said “Every nation ought to endeavor to possess within itself all the essentials of national supply. These comprise the means of subsistence, habitat, clothing and defence.”

Globalism rejects this nationalistic program of acquiring resources. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the goal has been cooperation over confrontation, inter-dependency over independence. We saw examples of this in the expansion of the European Union and NATO, the admittance of China into the World Trade Organization, the now-defunct Trans-Pacific Partnership, and the Iran nuclear deal.

Now the pendulum has swung the other way, with a backlash against globalism and towards nationalism, manifested in Brexit, the election of populists like Trump and far-right European parties, the China-US trade war, the end of the TPP, and the Trump Administration gutting the deal with Iran and re-imposing sanctions.

Winners and losers

Suppose there is a war – either a Cold War or a shooting war – between the US and China, or the US and Russia. Who would win? The US by far has the most military might, so in the short-term, it’s hard to imagine America losing to either.

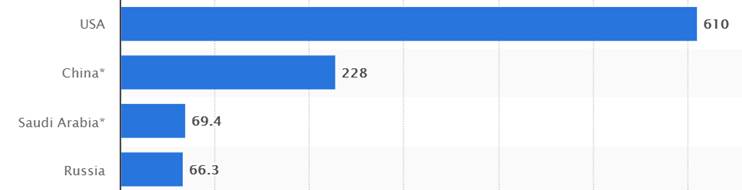

In 2017 the US spent $610 billion on its military – the most of any country by far. The next closest was China at about a third, or $228 billion. China’s military spending is 1.9% of GDP compared to 3.3% in the US; Russia’s is 5.3%, but it only spent $66.3 billion in 2016 – a tenth of US expenditures. The United States maintains 800 military bases in over 70 countries, compared with 30 between Britain, France and Russia combined. China just opened its first one, in Djibouti, Africa.

The capacity of the United States Military to project power overseas, along with its tremendous arsenal of conventional and nuclear weapons, advanced technology and high numbers of Armed Forces personnel (the US has 1.4 million active frontline personnel, more than Russia’s 766,500 but smaller than China’s 2.3 million), afford it the ability to contain China and Russia. In an all-out war, all the US Military needs to do is blockade the supply lines of its enemy(ies).

But if the war were to continue, it would be another story. The United States is far more dependent on China and Russia, particularly China, for its critical minerals. And without critical minerals, it’s difficult to re-stock weaponry and equipment lost on the battlefield, or to keep up with an arms race.

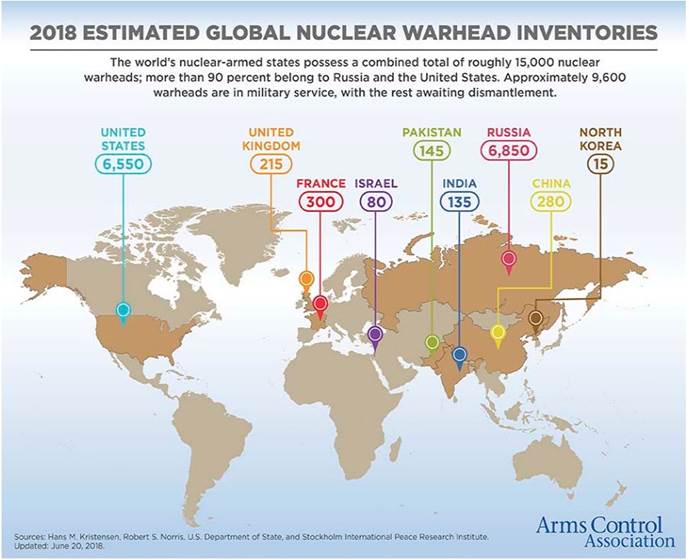

An arms race isn’t only about nuclear weapons. Russia and the US have about the same number of nuclear warheads (see map below), but nukes are only used for deterrence; nobody wants to ever have to use them. Conventional military equipment, weapons and personnel (army, navy, air force) are far more likely to be deployed in a potential confrontation, like in Crimea or the South China Sea.

Of critical importance is supplying your military in a war, or a Cold War. What would the US do if conflict escalated to a level where China refused to sell its rare earths? The military would have to scramble together a source of materials for widely used permanent magnets, used in aircraft engines and in the noise cancellation technology blades of stealth helicopters, for example. Battery metals for electronics, including lithium, graphite, cobalt, and rare earths, would all be in huge demand. The demand for steel alloys needed for aircraft, ships and vehicles would suddenly explode. How would the US quickly get its hands on enough chromium, beryllium, manganese, vanadium, titanium?

Because of the already mentioned 15 years to fix the US broken supply gap regarding the critical metals related to its defense prolonged conflict would favor Russia or China in these circumstances. That’s because both Russia and China have more critical minerals than the US and would be able to out-build the US Military in an arms race scenario, and out-replenish broken or destroyed equipment in the event of a long, drawn-out war involving ships, airplanes, tanks, etc. Even more so if it was the United versus China and Russia.

Russia and China have since 1950 agreed to defend one another against an attack from US-backed Japan or its allies (China backed North Vietnam and North Korea) so continued cooperation is unsurprising. In 2001 Russia’s Vladimir Putin and then-Chinese President Jiang Zemin signed a 20-year agreement to “increase trust between their militaries.” The two countries now regularly participate in joint maneuvers including joint naval exercises to counter US influence in the Asia Pacific region.

Of course, neither Russia nor China is free of imports of military materials. China for example imports much of its lithium. Beijing has been frantically seeking offtake agreements in South America’s “lithium triangle” in order to lock up a supply of lithium needed for electric vehicles, of which it is the world leader.

Among Russia’s top five importers are China and the United States, making Russia vulnerable to a trade embargo on materials needed for weapons or equipment. Russia surely buys a high percentage of its rare earths from China, which controls 95% of the market.

Conclusion: A US mining renaissance

How will the United States ever catch up to China and Russia with respect to its lack of materials for defending territory and projecting military force? The US has the strongest military, but the weakest metals supply infrastructure compared to China and Russia. With an economy that has moved away from raw materials and towards other things – tech, pharmaceuticals, banking, real estate, etc. – the United States no longer has the industrial base it needs to be its own military supplier. It must rely on foreign countries for critical metals like rare earths, manganese, vanadium, etc.

The US has some reserves of these materials, but it has all but stopped mining them. Why? It’s a combination of NIMBYism- nobody wants a mine anywhere close to them, and environmental regulations have become so onerous that apart from Nevada, mineral exploration in most of the country is painfully slow. And the fact that it was just a whole lot cheaper to import them from China and Africa. Why look for cobalt when you can ship it over from the DRC at a fraction of what it would take to mine it here?

The fact is, though, America has dropped the ball on mining and it may be too late to pick it up. Even if the US were to suddenly allocate billions of dollars for critical mineral exploration, it takes years to find a deposit, prove it economic, and build the infrastructure needed for mining.

Import dependence was fine in an era of globalization, but not in the current international relations of nationalism and resource nationalism. An inability to supply your own military with the basic building blocks of modern technology is a weakness an enemy is bound to exploit.

Russia, and increasingly China are becoming more and more emboldened, their military aggression becoming almost every week more evident. Is it because they realize that the US military is in reality a paper tiger unable to conduct military operations past a first wave of hardware expenditures? After all, you can’t fight much of a war if you cannot replace destroyed equipment, and even a short war of attrition would expose US supply chain weakness.

The United States, if, at the very least, is going to continue to keep Russia out of it’s back (South America) and front (Arctic) yard, and China contained – as in not controlling the South China Sea and invading Taiwan – needs to have a US mining renaissance.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.