We are the Lemmings

2019.02.12

What were you doing on August 1, 2018? Likely it was just like any other day, with your thoughts on work, your spouse, your kids, money, what to make for dinner, etc. What you should have been thinking about though, was the Earth.

August 1 was Earth Overshoot Day. What does that mean? Well, Earth Overshoot Day is the day of the year when humanity has used more resources from nature than can renew in that entire year. The date is moving closer to January, meaning every year we use up more natural resources, faster.

That’s a problem, because without a way to replace all the resources we consume – harvested food, fertilizers, energy, metals, etc. – we are gradually depleting nature’s bounty, at a rate that is unsustainable, long-term. If we keep going, and economies keep growing, we’re eventually going to run out. The problem is made worse by the global population increasing, along with the continuing wants of people in the developed world (“the West”) and in less-developed countries (who are demanding houses, cars, fridges, cell phones, etc.), putting more pressure on our finite resources.

This article will take a look at how unsustainable our voracious consumption has become, and how we might live more sustainably in order to #MoveTheDate, in Twitterspeak, back not forward.

Earth Overshoot Day

The day of the year humanity’s consumption becomes unsustainable, started being marked in 2006. The project of compiling this data is performed by the Global Footprint Network (GFN), an international research organization.

Since then, the date has been marching forward every year. In other words, every year our consumption becomes less sustainable. To put this in terms everyone can understand, Earth Overshoot Day 2018 meant that Earth’s population used a year’s worth of resources in seven months. August 2 was the point when we consumed all the meat, fish, grains, energy, etc. (whatever can be made naturally) that nature can regenerate over a year, through over-farming, over-fishing, over-extracting, over-heating or cooling, and over-polluting.

Put another way, in 2018 it would take 1.7 Earths to feed, clothe and sustain the planet’s 7.6 billion people for a year. After August 1, the rest of the year was “overshoot”.

When the first overshoot calculation was announced in 2006, that date was Oct. 9, now it’s the beginning of August.

GFN calculates the biocapacity and ecological footprint of every country to determine which is living beyond their means. This is measured in hectares. The US has a biocapacity of 3.6 ha per person but average consumption is 8.4 ha, leaving a per-capita deficit of 4.8 ha. Extrapolating that number to the population of 317 million, the United States used all its natural resources by March 15 according to the formula, explained by NBC News. Continuing the US rate of consumption worldwide would require the resources of five Earths. See the graphic below for country comparisons.

Earth Overshoot Day is often used to highlight the costs of such zealous overconsumption, including depletion of fresh water supplies, loss of animal/ fish habitat and species extinction, deforestation/ soil erosion, more CO2 in the atmosphere, and climate change – all topics we have covered extensively.

These costs are important, but we are more interested in how overpopulation and overconsumption are affecting the world’s natural resources – food crops, timber, pulp, oil, mined metals, etc. From GFN’s predictions, it doesn’t look good. The organization forecasts that by 2030, just 11 years away, Earth Overshoot Day will be in June – meaning it will take two entire Earths to sustain our species’ consumption.

Malthus revisited

Since 1950, the world’s population has gone from 2.5 billion people to 7.6 billion. No less than 75 million people a year are added to this number.

According to the United Nations, the world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by the year 2050, from its current 7.6 billion (and growing). A 2017 study in the journal Biosciencesuggested that to feed that number of people, global food production will need to increase from 25% to 70%.

Of course, the dilemma of a growing world population versus a finite amount of food able to be grown on Earth, is not a new problem. Thomas Robert Malthus, the English cleric and scholar, was writing about it as early as 1798. Malthus famously predicted that gains in living standards would be undermined, as population growth outstripped food production, thereby driving living standards down to subsistence levels.

The “Malthusian dilemma” has not come to pass mainly because of technologies that increased food production.

The Green Revolution helped kickstart the greatest explosion in human population in history – it took only 40 years (starting in 1950) for the population to double from 2.5 billion to five billion people.

We goosed agra-machine’s growth and saved a billion people who birthed billions more.

Norman Borlang, father of the Green Revolution, is on record as saying if we did everything right the Earth has a human carrying capacity of 10 billion people.

That’s great, but if the UN’s predictions are correct, we’re going to reach 10 billion souls very soon after 2050. What happens then? Will we all have enough food, or will Thomas Malthus be proved right?

Not enough to go round

The Earth might be big enough for 10 billion as Borlang believed. But the time is quickly coming when our sheer numbers will demand more than the Earth can possibly supply. A little bit of research reveals some disturbing statistics.

According to the UN’s International Resource Panel (IRP) report, the extraction of material resources – biomass, fossil fuels and non-metallic minerals – has tripled between 1970 and 2017 – reaching 88.6 billion tons. (Imagine what it would be if we included metallic minerals – copper, iron, tin, manganese, etc.)

Interestingly, while global material use has increased in large part due to the growth of China (there’s still India, Africa and another billion or so people to count), “there has been little improvement in global material efficiency since 1990. The global economy now needs more material per unit of GDP than it did at the turn of the century, the IRP says, because production has moved from material-efficient economies such as Japan, South Korea and Europe to far less materially-efficient countries such as China, India and some in south-east Asia.”

Another report, from the UN’s Environmental Program, said materials extraction is expected to hit 140 billion tons by 2050 unless consumption is drastically reduced. The report warned “the prospect of much higher resource consumption levels is far beyond what is likely sustainable.”

Unsurprisingly, there are large gaps between rich and poor countries as far as consumption habits. People in wealthier nations use an average 16 tons of minerals, fossil fuels and biomass (fuels and other products from plants) per year. In contrast the average citizen of India only consumes four tons a year.

Worldwatch.org reports that:

- Households spent $20 trillion on goods and services in 2000, four times the amount spent in 1960 (in 1995 dollars).

- A rising US population means that Americans will consume 5 million tons more meat in 2050, even if the average American were to eat 20% less meat.

- In Europe 89% of the population are considered heavy consumers, versus just 16% in China and India, suggesting hundreds of millions of people in these countries are going to demand more goods and services.

- In most developing countries the consumer class in under half of the population.

- The 12% of the world’s population living in North America and Western Europe account for 60% of global household consumption. One-third of the people living in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa account for only 3.2%.

- At less than 5% of the world’s population, the US uses about a quarter of the world’s fossil fuels.

The countries with the most natural resources are, in order: China, Saudi Arabia, Canada, India, Russia, Brazil, the US, Venezuela, the DRC and Australia.

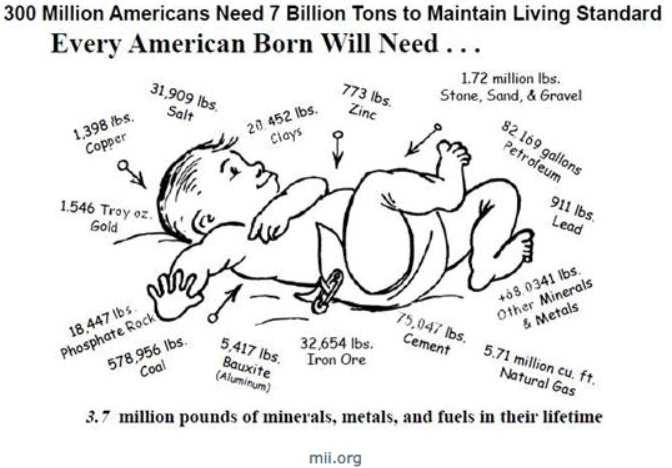

Another 2.1 billion people will be added to the world between now and 2050. Most will not be Americans but they are going to want a lot of things that we in the Western developed world take for granted – electricity, plumbing, appliances, AC etc. What if all these new consumers were to start consuming, over the next 10 years, just like an American? What’s going to happen to the world’s mineral resources if a billion more “Americans” are added to the consuming class? Here’s what each of them would need to consume, per year, to live the American lifestyle…

The question is, and we’ve asked it before, will everyone be able to buy enough resources to live like an American? The answer is a resounding no!

Another way to look at this, is based on population growth statistics, by 2050 the world economy will be four times larger than today. To have the same per-capita consumption of Canada would require a world economy 15 times its current size!

Worldwatch reports the planet currently has 1.9 hectares of productive land per person to supply resources and absorb wastes, but the average person uses 2.3 ha. An American has an ecological footprint of 9.7 ha versus the average resident of Mozambique who uses just 0.47 ha.

Can we produce enough food, metals and energy to handle 15 times more economic activity in the next 30 years? No. We neither have the resources in the ground, nor the amount of land, water and fuel required. And we haven’t even talked about what this would do to the planet – that’s next.

If you don’t believe me, take copper and an example.

Total mined copper was just under 20 million tonnes in 2017.

Global refined copper demand has risen steadily from 2005, when it was around 18 million tonnes, to the current global consumption of about 24 million tonnes. Immediately we can see that demand is currently outstripping supply by about 4 million tonnes, annually.

Even if we mined every last discovered, and undiscovered, pound of land-based copper, the expected 8.2 billion people in the developing world would only get three quarters of the way towards copper use parity per capita with the US, if we assume 10 billion by 2050.

Of course the rest of us, the other 1.8 billion people expected to be on this planet by 2050, aren’t going to be easing up, we’re still going to be using copper at prestigious rates while our developing-world cousins play catch up. Copper-use parity isn’t going to happen, it can’t.

Wrecking the Earth

The negative effects of all this rampant consumption have been well documented elsewhere, so I won’t get into too much detail.

EcoWatch warns that the tripling of resource extraction since 1970 will accelerate the acidification of the world’s oceans, cause eutrophication (oxygen depletion) of soils and waterways, and lead to greater amounts of waste and pollution.

The environmental site also notes that “Growing primary material consumption will affect climate change mainly because of the large amounts of energy involved in extraction, use, transport and disposal.”

Read our five-part series on climate change (scroll to the bottom)

Conclusion

We are seeing the results of ecological overshoot in species extinction, freshwater depletion, soil and air degradation and the obscene piling up of garbage on land and in the oceans. Poisoning our environment with herbicides, pesticides and fertilizers, while unsustainably reaping the world’s finite resources enables us to support a growing population and a developing nation consumerism to get what developed nations have. But we consume our yearly renewable resources in 7 months and we’re quickly draining the world of finite resources – copper, zinc, aluminium and gold, to name a few, are already in structural supply deficits

Our reality is we live on a finite resource world while our appetite for its resources is infinite. Unstoppable growth is going to meet hard reality. The unsustainable consumption of both finite and renewable resources is a major problem that will, if left unchecked, lead to shortages, widen the divide between rich and poor, and at its extremes, could result in a widespread breakdown of social order.

What to do about it?

It’s a question well worth considering because we are the lemmings rushing headlong over a cliff to certain destruction. We don’t claim to have all the answers, but part of the problem lies in how we address sustainability. We talk of sustainable resource extraction on a very micro level, without thinking about the macro, the global picture. We have caused extinction of countless species through destruction of their environment. Yet we have learned nothing about saving ourselves from the same fate.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd is on Twitter

Ahead of the Herd is now on FaceBook

Ahead of the Herd is now on YouTube

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.