US to cut rates, gold bull market remains intact – Richard Mills

2026.02.13

Gold and silver’s dramatic pullback on Jan. 30 was supposedly predicated on the notion that Trump’s pick to replace Jerome Powell as Fed Chair, Kevin Warsh, is a fiscal hawk who has previously criticized quantitative easing, wants to unwind the Fed’s massive balance sheet, and may not lower interest rates as Trump has long criticized Powell for failing to do.

But a deeper reading into Warsh reveals that he is not the hawk many think he is, and in fact is likely to move the Fed in lock step with the President’s low-interest-rate, low-dollar desires.

Whether or not that is the right thing to do is a matter of some debate. What I do know is that Warsh’s appointment to the Fed will be good for gold, along with a litany of other reasons I outline here.

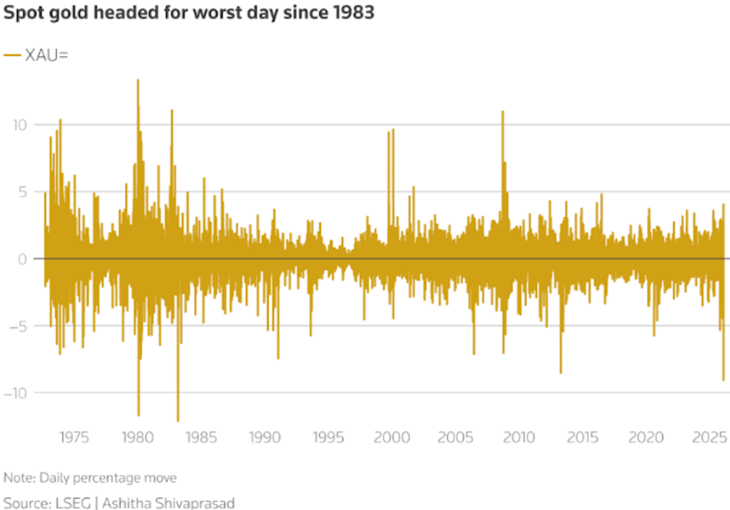

Gold drops 9.5%

Let’s start with what happened to gold at the end of January. From a record peak of $5,594 an ounce on Thursday, Jan. 29, gold suddenly fell 9.5% on Friday, Jan. 30 to 4,883/oz as of 1:57 pm Eastern time. Why did traders dump gold? The selloff was sparked by President Trump announcing that he plans to nominate Kevin Warsh, a former Federal Reserve governor, as Fed Chairman once Powell’s term runs out in May.

There was also no doubt some profit-taking, with gold having appreciated a whopping 66% in 2025, and traders forced to sell to cover margin calls.

A ‘practical monetarist’

In a way, it was an odd choice. As stated, Warsh is more of a fiscal hawk than a dove, meaning he may not choose to lower interest rates and could even raise them, to deal with persistent inflation.

On the other hand, Warsh has criticized the past and current Fed, putting him in the Trump camp. He has called for a “regime change” at the central bank, arguing that current economic models, which focus on consumer spending and wage-driven inflation, are incorrect.

According to Forbes, Warsh believes the Fed drifted too far from its original mission by engaging in quantitative easing post-2008. He called the Fed’s covid-19 response “the greatest mistake in macro economic policy in 45 years.” And he has called for a reduced Fed balance sheet, which could mean the sale of bonds. Although the Fed’s assets have declined from their 2022 peak, they still total roughly $6 trillion today.

So where does Warsh stand on monetary policy? He is widely considered a “practical monetarist”, meaning he is focused on controlling inflation through changes to the money supply rather than relying solely on changes to interest rates. In Warsh’s view, inflation is mostly the result of excessive government spending and money creation, hence the need to reduce the Fed’s balance sheet.

But Warsh has also advocated for lower interest rates, arguing that the AI productivity boom will suppress inflation and enable cuts.

His logic is that widespread AI adoption in industries could produce more goods and services at lower costs, curbing inflation through increased supply. The Washington Post noted, “The Trump administration is betting that AI adoption will raise labor productivity, driving wage growth and economic expansion without triggering rapid inflation,” adding that Warsh aligns with this strategy, providing its theoretical foundation. (The Chosun Daily)

Trump has frequently complained that interest rates aren’t low enough to sufficiently boost the economy. He has also faced pressure to lower mortgage rates, which are based on the 10-year Treasury yield. Mortgages briefly topped 7% in early 2025.

The Washington Post quoted a Yale professor and a former director of the Fed’s division of monetary affairs saying that Warsh could conflict with Trump if all he does is lessen the Fed’s balance sheet.

“It’s hard to see how that would be consistent with lower mortgage rates, and that creates some tension with the president,” said Bill English.

The Fed influences borrowing costs by adjusting its short-term benchmark interest rate, known as the Federal Funds Rate. Long-term rates, such as the 10-year and 30-year Treasury note, are set by the bond markets.

While it remains unclear exactly what Warsh would do if confirmed as Fed chair, one source expects him to support additional modest rate cuts in the near term, and that he is highly unlikely to significantly wind down the Fed’s balance sheet, which is expected to remain at current levels for a long time.

Warsh is also expected to lead a less interventionist Fed, as evidenced by this speech in April, quoted by WaPo:

“Each time the Fed jumps into action, the more it expands its size and scope, encroaching further on other macroeconomic domains,” he said. “More debt is accumulated … more capital is misallocated … more institutional lines are crossed … risks of future shocks are magnified … and the Fed is compelled to act even more aggressively the next time.”

Interest rates and gold

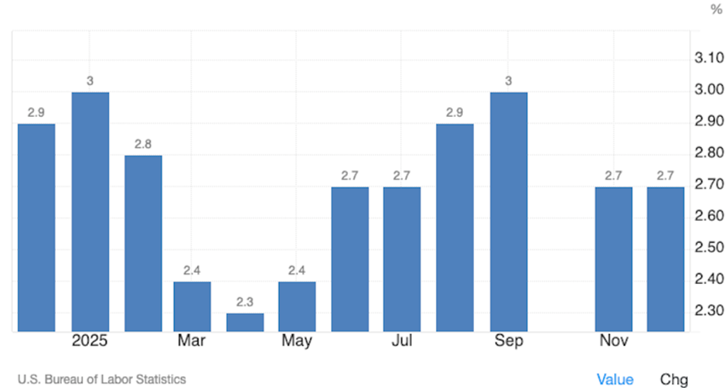

Market expectations are for two additional 25-basis-point cuts this year, starting in June or July.

David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital anticipates the Federal Reserve will cut more than twice in 2026.

If that were to happen, it would undoubtedly be good for gold.

According to analysts at UBS, quoted by Kitco News, A further decline in real U.S. rates will help support investor demand for gold exchange-traded funds (ETF) by lowering the opportunity cost of holding the non-yielding metal, while central banks are expected to continue adding to their reserves.

The UBS analysts noted that the announcement of Warsh’s appointment eased fears that appointing a more dovish candidate could accelerate the recent weakening of the US dollar. The dollar did initially strengthen on the news, but it has since fallen back. Rate cuts will accelerate the slide.

The UBS analysts forecast that gold will end the year at $5,900.

The argument for rate cuts

A softer economic outlook has strengthened expectations of lower interest rates.

One of the most troubled sectors is manufacturing, which is shedding jobs like you wouldn’t believe, as Trump would say. According to the ADP private employment report, the manufacturing sector lost about 8,000 jobs in January, which marks the 32nd consecutive monthly decline, the longest losing streak since data began in 2010.

In 2024 and 2025, manufacturing employment fell 154,00 and 177,000, respectively. Since the 2022 peak, around 403,000 jobs have been eliminated, bringing total manufacturing employment down to 12.483 million, the lowest since 2021.

In a tweet, the Kobeissi Letter says the sector has now lost half the number of jobs wiped out during the 2020 pandemic, and that the US manufacturing sector is in recession.

We also need to look closely at retail sales for an indication of the economy’s health, since consumers represent two-thirds of GDP. The latest numbers show US retail sales stalled in December, “potentially setting consumer spending and the economy on a slower growth path heading into the new year,” says Reuters.

“The weak report, together with a marginal rise in business inventories, prompted economists to downgrade their economic growth estimates for the fourth quarter.”

Not only are consumers spending less, but they are also saving less — no surprise given that US inflation is currently running at 2.7% — higher than the Fed’s 2% target — and that many US imports are more expensive due to tariffs. The savings rate fell to a three-year low of 3.5% in November, two points under October’s 3.7%. The rate is a long ways from its April 2020 peak of 31.8%. “U.S. households accumulated about $2.3 trillion in savings in 2020 and through the summer of 2021, above and beyond what they would have saved if income and spending components had grown at recent, pre-pandemic trends” – FEDS Notes.

Reuters notes that Spending has largely been driven by upper-income households, who have benefited from the higher asset prices, while lower-income households are barely keeping their heads above water amid slowing wage gains…

The Atlanta Federal Reserve cut its fourth-quarter GDP growth estimate to a 3.7% rate from a 4.2% rate.

In other words, retail spending is tanking and that is lowering economic growth expectations.

One bright spot in the economy came Wednesday in the form of January’s nonfarm payroll data. As reported by CNBC,

Nonfarm payrolls increased by 130,000 for January, above the Dow Jones consensus estimate for 55,000, according to seasonally adjusted figures the Bureau of Labor Statistics released Wednesday. The total also was an improvement over December, which saw a gain of 48,000 after a slight downward revision.

But we still have manufacturing employment plummeting.

The argument against rate cuts

Here’s the problem with rate cuts in the current economic environment: The US government must either borrow money or print money to meet its financial obligations. Money-printing is inflationary, so the preferred option is to borrow.

Borrowing at low interest rates is preferable because it means that when bonds mature, and the interest is due, there is less to pay out than if interest rates were higher.

But the deficit and the debt keep climbing, and bond holders are demanding higher interest rates to hold bonds that are becoming increasingly risky given the country’s high indebtedness.

The numbers are alarming.

America reportedly borrowed $43.5 billion a week in the first four months of the fiscal year, which starts in October. The interest on that debt works out to over $1 trillion for 2026. Interest in 2024 and 2025 also exceeded $1 trillion.

If borrowing continues at this rate, the deficit will reach $1.8 trillion or higher, says the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

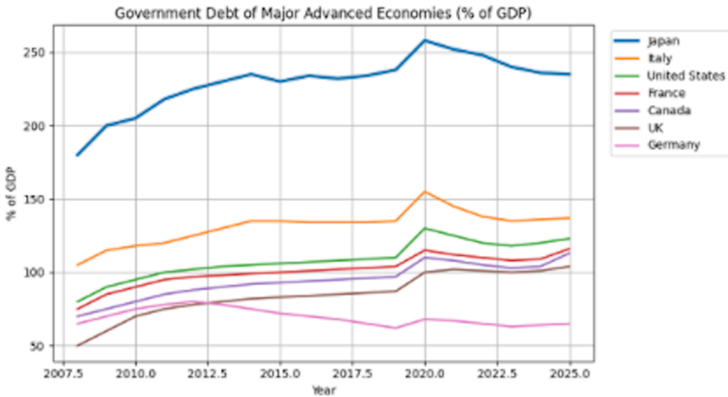

The $38.5 trillion national debt now exceeds Gross Domestic Product of $31 trillion. The debt is simply the accumulation of prior deficits.

The annual deficit is predicted to grow to $3.1 trillion by 2036, and the US debt is forecast to hit $64 trillion by the same year. In 2030 the debt to GDP ratio will likely reach 120%, beating the previous record of 106% reached right after World War II.

“There’s no sugar-coating it: America’s fiscal health is increasingly dire,” Reuters quoted Jonathan Burks, economic policy director at the centrist Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington. “Our debt is now 100% of GDP, and rather than pumping the brakes, we are accelerating. These large deficits are unprecedented for a growing, peacetime economy.”

Rising yields on government bonds are a red flag on government spending, with investors demanding higher premiums because the perceived risk of the lending has increased.

The current yield on the 10-year Treasury bond is 4.1% and the yield on the 30-year bond is 4.7%.

Trump, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and the future Fed Chair, Keven Warsh, all want low interest rates. But long-term rates will have to rise to attract bondholders. The US can’t afford to lose bond holders, because they finance the US government’s deficit spending.

Note that competition for higher bond yields is heating up with Japan’s recent election of its first female leader, Sanae Takaichi. Japanese government bond (JGB) yields have been rock-bottom low for years, but the election of Takaichi and her governing LDP party to a two-thirds super-majority in the parliament’s lower house made bond prices fall and lifted 10-year JGB yields above 2.35%, reports Bullion Vault.

Japan is the mostly highly indebted nation among the G7 as the chart below shows. Takaichi won on a promise to increase government spending, despite government debt reaching $7.2 trillion at the end of 2025, with the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeding 230%, almost twice the level of the US.

The reason JGB rates rose is that Takaichi’s policies require more debt issuance, meaning a higher rate is needed to attract investors.

As Japanese bond yields rise, bond yields elsewhere, including the US, will be pressured to go up to remain competitive.

This, in a short summary, is the Fed’s dilemma: they want to keep interest rates low to goose the economy and when Warsh gets in, to please Trump, and to keep interest payments as low as possible on government debt, but the way the US is going, it is losing bond-holders due to Trump’s “America First” policy (more on this below) and the only way to attract investors is for long-term rates to rise.

Bonds

Remember, the only interest rate the Fed can control is the overnight rate or Federal Funds Rate. Short-term Treasury bills like the one-month and the one-year are most heavily influenced by the FFR.

Who’s going to want to buy short-term Treasury bills when interest rates start dropping and yields go to say 1%?

As for long-term rates, the Fed doesn’t control them, and there will be market pressure for them to rise, especially due to intervention by the “bond vigilantes”.

Bond prices and yields have an inverse relationship. When yields go up prices drop, signaling a lower demand for Treasuries. If the Fed increases interest rates, yields generally rise.

There is a group of powerful investors that not only watch US Treasury yields closely, but they also take an active part in influencing the bond market, especially if they don’t like the economic policies of the administration.

Bond vigilantes are investors who sell government bonds in response to fiscal policies they view as inflationary or irresponsible, driving up borrowing costs for the government. — Investopedia definition

In a column, ‘Paydirt’ Editor Doug Hornig makes some good points regarding how the bond market is signaling that confidence in the full faith and credit of the US government has plummeted:

- It’s particularly important to keep an eye on the long bond (30-year Treasury), looking for a 5% yield. Think of that 5% rate as a formidable barrier. It was breached in the fall of 2023, and the spring and summer of 2025, and has been approached on numerous occasions. But as yet it has always drawn back. Why? There is nothing magical about a 5% yield. But it carries a disproportionate weight with the “bond vigilantes.”

- Buying long bonds is a vote of confidence in the system. But if they see worrisome fiscal or monetary behavior on the part of government, they dump bonds.

- In September and October of 2025, there was a brief period of optimism that drove long bond yields from near 5% down to 4.5%. Then gloom set in. Yields rose and have been stuck around 4.8% from then to the present.

- I can’t say what the bond vigilantes will do next. But the fundamentals that underlie the current trend are unchanged: too much federal debt, excessive money creation, financial and geopolitical instability, stubborn inflation. I would say that breaking through that 5% barrier is a very distinct possibility.

- If yields exceed 5% and stay there: mortgage rates rise to 7-8%, stifling a housing market that is already teetering; government interest expense snowballs, and the U.S. feels the political and fiscal pain very quickly; leverage dries up; and the flight to safety factor intensifies, pulling capital from other assets, like stocks. Equities decline.

- There is a delicate interplay between gold and bond yields, as investors perpetually re-define what constitutes the ideal safe harbor. In general, rising yields put a damper on gold. Yet the gold bull has continued onward, in defiance of the long bond —especially since 2022, as the yield has climbed by three full basis points while gold skied from under $2,000/oz to near $5,000 today.

- Though gold earns no interest, it has become viewed as more of a haven than long bonds. Outside of the U.S., central banks are divesting from their Treasuries and stockpiling gold.

- If the Fed adheres to an easy money policy—which it seems committed to doing—it will ignite inflation and devalue the dollar. Gold has always been the ultimate protection against that scenario.

Before we leave bonds, a word on corporate bonds, which also feed into the US being a highly indebted nation.

The capital expenditures on data centers by tech companies intent on staying ahead of the AI boom is truly remarkable.

Barron’s said recently, the four biggest hyperscalers — Microsoft, Meta, Amazon and Google — are expected to deploy around $650 billion in capex this year, with an increasing share funded by the bond market.

Google, in fact, reportedly unveiled plans for a $15 billion sale of high-grade debt on Monday, following a well-received issue of $25 billion in new debt from Oracle last week.

Worsening fiscal picture

The evidence shows that Trump’s economic policies are worsening the country’s fiscal picture amid low economic growth.

The Congressional Budget Office says the deficit will grow from about 5.8% of GDP in 2025 when Trump took office, to 6.1% over the next decade, reaching 6.7% in fiscal 2036. Bessent has said he wants to shrink the deficit-to-GDP ratio to 3%.

The CBO and the administration also have differing growth projections, with the CBO forecasting real GDP growth of 2.2% in 2026, trailing to an average 1.8% for the rest of the decade, versus the administration’s far more robust 3-4% range for 2026.

Remember Warsh saying that the artificial intelligence productivity boom will suppress inflation and enable rate cuts? The CBO projects only a nominal GDP boost from AI productivity gains, downplaying a linchpin of the administration’s demands for lower interest rates.

The non-partisan budget referee agency also projects interest rates on 10-year Treasury notes to remain roughly where they are now and rise to 4.3% in 2027 — another blow to Trump’s hope for sharply lowering borrowing costs.

Overspending

Continued bloated government spending is the primary culprit.

Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill”, which extended the 2017 tax cuts, and slashed outlays on social programs such as Medicaid, will add $4.7 trillion to US deficits over the next 10 years. Tariff revenue will admittedly ease the pain by reducing deficits by about $3 trillion.

Military spending is another large budget item. In early January Trump proposed setting military spending at $1.5 trillion in 2027, citing “troubled and dangerous times.” That’s significantly higher than the 2026 military budget of $901 billion.

“This will allow us to build the ‘Dream Military’ that we have long been entitled to and, more importantly, that will keep us SAFE and SECURE, regardless of foe,” Trump said in a posting on Truth Social announcing his proposal, via PBS.

How is all this spending going to affect interest costs? The CBO forecasts the Trump administration’s spending cuts, such as those carried out by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) are dwarfed by the growth in net interest costs on the ballooning federal debt, which are set to more than double to $2 trillion by fiscal 2035 from $970 billion in fiscal 2025.

De-dollarization and geopolitical events

The US is dedicating funds to re-arming its military — already the most powerful in the world by far — while it removes itself from international treaties, picks fights with its closest allies, cuts itself off from free trade by erecting a giant tariff wall, and acts belligerently outside its borders.

In recent weeks the Trump administration has captured Venezuelan President Maduro and placed him into federal custody to face narco-terrorism charges in New York; seized Venezuelan oil tankers; amassed a large military force in the Caribbean Sea as it aims to re-invent “The Monroe Doctrine” to “the Donroe Doctrine”; cut off Venezuelan oil to Cuba, causing a fuel crisis; has suggested carrying out military operations in Colombia; and continues to covet Greenland for polar defense and to gain control over its critical minerals.

On Feb. 10, the US State Department said on social media that it was “concerned about latest reports that Peru could be powerless to oversee Chancay, one of its largest ports, which is under the jurisdiction of predatory Chinese owners.”

It added: “We support Peru’s sovereign right to oversee critical infrastructure in its own territory. Let this be a cautionary tale for the region and the world: cheap Chinese money costs sovereignty.”

The $1.3 billion facility was built to provide China with a direct gateway to the resource-rich region. Key trade items include copper, blueberries and soybeans from Brazil. It also close to the “lithium triangle” formed by Chile, Argentina and Bolivia.

China challenges US in South America with new port in Peru — Richard Mills

Meanwhile, the rift between America and Europe is growing wider by the day. A high-level European official told Politico about a “change in mindset” that is taking place, where Europeans are realizing that Americans increasingly seem to view Europe less like allies than rivals. “It has completely changed from the times when there was cooperation between us, now we’re in a power struggle.”

Examples of conflict include the US embassy in Denmark removing 44 small Danish flags that commemorated the Danes who died in Afghanistan; the audience at the Winter Olympics opening ceremony booing Vice President JD Vance over news that American federal immigration agents would provide security during the Olympics; and European leaders looking to do more business with countries in South America and China.

Politico reports the leaders are re-thinking agreements with American defense contractors and openly discussing the viability of NATO. Large majorities of people in Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Great Britain now have an unfavorable view of the US, with more than 60% of the public in all six countries now seeing the US in a negative light, according to the publication.

In Canada, the number of travelers crossing the border by land and air continues to languish.

De-dollarization/ Central bank buying

I’ve previously talked about de-dollarization as the movement, especially among developing countries, to sell US assets and start conducting trade in their own currencies.

These countries saw what happened to Russia when it invaded Ukraine in 2022: the freezing of $335 billion in Russian central bank funds in the United States and allied countries. They didn’t want this to happen to them, so they began dumping USD-denominated assets.

The BRICS countries are moving away from the US dollar as the currency that settles international transactions, and gold is an integral part of the new settlement mechanism.

BRICS launch gold-backed currency — Richard Mills

China has been reducing its US Treasury holdings since 2013 as part of a broader effort to become less reliant on the US dollar, although it still owns around $682 billion in US government debt, making it the third largest creditor behind the UK and Japan.

This week Bullion Vault reported that financial regulators in China have urged commercial banks to limit purchases of US government bonds. Reaction in the bond market was muted, probably given that China has been a net seller of US Treasuries for nine straight months.

However, according to Barron’s,

Any ‘quiet quitting’ by Chinese banks would add to growing concern that foreigners are exiting the Treasury market because of worries over the staggering size of U.S. debt. The more the debt supply, the higher the anxiety the U.S. won’t be able to pay back its lenders.

Instead, the People’s Bank of China grew its gold bullion reserves in January to 2,308 tonnes, marking the 15th consecutive month of gold reserve accumulation.

Globally, the World Gold Council reported that central bank gold demand remained firm up to November 2025, with net purchases totaling 52 tonnes, and year-to-date figures pushing 297 tonnes.

November’s top buyers in order were Poland, Kazakhstan, Brazil, Turkey and China.

BNN Bloomberg’s Andrew Bell asked Brooke Thackray, research analyst at Global X Investments Canada, whether gold’s long-term drivers are still in place, such as currency debasement. Bell also wanted to know if the gold trade has become too crowded.

The two spoke as gold and silver rebounded from the flash crash on January 30th.

Thackray noted that gold is still a relatively small portion of investor and institutional portfolios, “so I don’t think we’re done.”

He said the drivers are still there especially buying by central banks, particularly in the East. However, while volatility will continue, Thackray thinks gold will be range-bound for the next while.

I believe gold will stay above $5,000 and silver will lock in around $85.

Retail

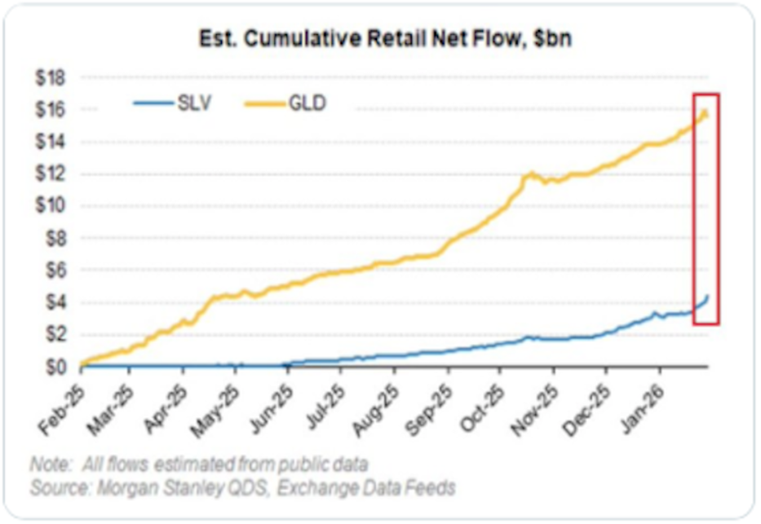

Another answer to the question whether “gold is done” comes via The Kobeissi Letter. In a tweet, the Letter notes that retail investors are piling into gold and silver funds, with the largest gold ETF, GLD, attracting over $16 billion in inflows over the past year.

Over the last five months, investors bought +$9B of GLD. In January, global gold ETFs posted +$19B in inflows. “Retail is going all-in on gold and silver.”

Conclusion

Trump’s appointee to the Federal Reserve chair is a monetarist who will toe the president’s line of lowering interest rates. The US dollar will fall in lock step and precious metals, actually all commodities, will rise.

The Fed is stuck between a rock and a hard place, to quote a well-worn cliche. On the one hand, it needs to keep rates as low as possible, not only to goose the economy and keep borrowers happy, but to lessen interest payments on government debt.

These payments are already at $1 trillion a year and they are on track to reach $2 trillion if spending and borrowing aren’t reined in.

But if bond yields drop, the government risks losing bond holders, something that it can’t afford to do. In a way it doesn’t matter what the Fed does, since it only controls short-term not long-term paper.

If the bond vigilantes don’t like what they’re seeing, with all the government debt, they will send a signal by selling bonds, causing yields to rise.

If the yields surpass 5%, look out. The US will quickly feel the political and fiscal pain, and the flight to safety will intensify, pulling capital from stocks and bonds and towards gold.

Gold was already at a record-high of around $2,700 when Trump became president for the second time. Now it’s almost double at $5,000. Gold this high is a reflection of global instability, especially with Trump as president and commander-in-chief.

Gold and silver are considered safe havens when the economic outlook is uncertain.

As the US dollar weakens, as one video put it, “the shock waves go global”. There are three forces to watch, and all are pointing to higher gold: the US dollar, interest rates, and geopolitical tensions.

As uncertainty grows, confidence in the dollar is being tested, and countries are responding by reducing dollar exposure.

Demand for gold isn’t going anywhere but up. The gold bull market remains intact, and prices for the rest of the year should reflect that.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.