US stands to gain from Chile’s lithium restrictions

2020.11.14

Everybody in the lithium game knows about the lithium triangle.

Straddling three countries – Bolivia, Chile and Argentina – the lithium triangle is said to contain three-quarters of the world’s lithium reserves.

But the highest-quality lithium and the cheapest costs of production are in Chile, which alone hosts about half the world’s lithium. So much, that the skinny South American nation has been referred to as “The Saudi Arabia of lithium’.

Chile’s lithium is purer than Argentina’s; purity is measured in parts per million of lithium brine hidden under “salars” (evaporated salt lakes) that are millions of years old. Its salars are higher in elevation than Argentina, meaning they are less likely to be flooded by rainfall, windier and drier, which reduces evaporations times, thus cutting the costs of production. There is currently no lithium produced in Bolivia, despite hosting the Salar de Uyuni salt flats, estimated to contain over a quarter of the world’s known reserves.

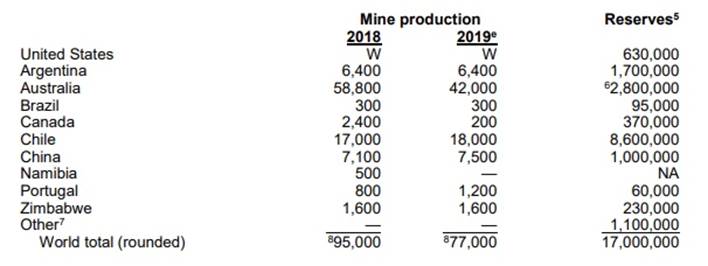

Chile is currently the second largest producer of the main ingredient of lithium-ion batteries installed in electric vehicles, behind Australia, home to the Greenbushes hard rock lithium/ tantalum mine jointly owned by China’s Talison Lithium and US-based Albermarle (NYSE:ALB). According to the US Geological Survey, Chile produced 18,000 tonnes of lithium in 2018 versus Australia’s 42,000 tonnes, out of the 77,000 tonnes per year lithium market (not including US production which is slight – there is only one lithium mine, Albemarle’s Silver Peak in Nevada).

When it comes to lithium deposits, though, Chile leads the world. According to the USGS, the country has 8.3 million tonnes of lithium locked away, over half of the globe’s 17Mt total.

The largest source of Chilean lithium is the Salar de Atacama.

One of the hottest, driest, windiest and most inhospitable places on Earth, the Atacama is ideal for lithium mining because the lithium-containing brine ponds evaporate quickly and the solution is concentrated into high-grade lithium products like lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide used in EV batteries.

The Atacama is the world’s highest-grade and largest-producing lithium brine deposit – responsible for supplying a third of the world’s lithium.

While Chile will undoubtedly play a major role in shipping lithium carbonate and hydroxide to electric vehicle battery makers, the center of the world’s lithium brine production is making it tough for lithium miners, especially foreign companies, to ramp up production of the mineral that is essential to the electrification of the world’s transportation system.

Lithium, obviously, is the key ingredient in lithium-ion batteries used not only for EVs but the lithium storage market which is growing fast, on the back of increased demand for renewable energy (wind, solar) storage.

Water fight

Chile’s lithium industry depends on pumping huge volumes of brines from beneath the Salar de Atacama, then evaporating it to create lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide.

But miners’ ability to get enough water for their operations is being challenged by environmentalists, farmer and the authorities, who say the actions of large companies like SQM (NYSE:SQM), the state-owned lithium miner, and Albemarle, are damaging the environment and shrinking water supplies. Local wildlife, such as flamingos, are also said to be in danger.

In 2019 a Chilean court, acting on a challenge by Atacameño communities, ordered authorities to rewrite a $25 million remediation plan agreed with SQM (NYSE: SQM) for environmental damage caused by its lithium operations, including excessive brine pumping.

SQM and Albemarle for years have blamed each other for over-exploiting their water rights in the Salar de Atacama, where they operate just 20 km apart. Sharing the same salar was bound to cause friction; it’s like sticking two straws into the same water glass. The Chilean government, fearing a water shortage, in 2018 put restrictions on water use in the salar.

It isn’t only lithium that is being affected, but copper and iron ore mining. Some of the world’s largest open-pit copper mines draw water from aquifers located high in the Andes, the rights to which are granted by Chile’s water authority.

According to The Northern Miner, Over the last decade, a dozen mining companies, including copper producer Antofagasta (LSE: ANTO), iron ore miner CAP Minería and Lundin Mining (TSE: LUN) have all built desalination plants to reduce pressure on scant or nonexistent ground and surface water supplies.

The country’s environmental regulator, SMA, is reportedly working on a comprehensive management plan for the Atacama salt flats, that would cover SQM and Albermarle. The Chilean government has long promised but has so far failed to deliver a water study of the Atacama basin.

For now, though, it is quite apparent that the government will do what it needs to do to protect domestic lithium producers, under the guise of environmental protection, at the expense of foreign interlopers, ie., Albemarle.

Edged out

In 2018, the Chilean government said Albemarle failed to live up to a 2016 contract. The company was supposed to offer a quarter of its annual production at a discount to battery makers – a stipulation put in to help build a mine-to-battery industry in Chile. The country’s nuclear regulator then refused to increase the company’s lithium production quota.

Fast forward to September, 2020, when Albemarle, the world’s largest lithium producer, again locked horns with the government, this time over how it calculates its reserves. While the company won approval in 2016 to hike its production from the Atacama flat, its export permit required that Albemarle prove its reserves, to sustain increased output. ALB claims it has delivered the information required. But if it loses the dispute, Albermarle could have its export permit suspended, once again thwarting its attempts to boost production.

Two months later, Chile is threatening to take the global chemicals company to arbitration over what it says are $11 million in unpaid royalties.

It’s enough to make a guest in a country feel, well, unwelcome.

Enter Codelco

Meanwhile Codelco, the state-owned miner that is the world’s number one copper producer, operating seven mines and four smelters in Chile, has entered the lithium market, confirming earlier rumors that it might do so.

The company is reportedly moving forward with plans to explore lithium at the Maricunga salt flat, the country’s second largest (but less than 5% of Atacama’s size), having recently received approval from local environmental regulators.

A little background reading reveals what’s really going on here. In 2016 the Chilean government published a new lithium policy, whereby state-run companies were directed to develop their claims over salt flats in northern Chile.

In 2018, Codelco got permits for the whole Salar de Maricunga, and last year, formed a joint venture with privately-owned Minera Salar Blanco to mine claims held by both companies. SQM, conveniently, also holds stakes in Maricunga, effectively tying up future production in the salar, to the exclusion of non-Chilean companies.

What has all of this meant for Chile’s lithium output? Export volumes have barely moved up or down in recent years. In fact, it has been reported, constitutional restrictions reserving lithium production for the state have pushed investors into developing mines in Argentina and Australia instead.

It makes me wonder, why would Albemarle continue to slog it out in Chile, with the government putting so many obstacles in its way? Especially considering that, as the world’s largest lithium miner, the company needs to keep growing production to maintain market share.

As we argued in A Beautiful Mine, one way for Albemarle to remain the top lithium dog would be to increase production in the United States. Lithium grades at its Silver Peak Mine, Nevada are in decline (the mine has been going since the ‘60s); a number of exploration companies are drilling in the Clayton Valley. One of those firms is Cypress Development Corp. (TSXV:CYP)

Cypress Development Corp. (TSXV:CYP)

In August, Cypress released an updated resource estimate on its Clayton Valley Lithium Project in Nevada. The new Measured & Indicated (M&I) resources represent a 57% increase in tonnes of material, and a 55% increase in contained lithium. There are also 100.4Mt of Inferred resources, averaging 986 ppm lithium. Measured resources grew to 574.1Mt or 3.3Mt (contained) lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE). In the Indicated category, resources increased to 355.6Mt or 2.0Mt LCE. The previous resource estimate tallied Measured and Indicated resources of 593.3Mt averaging 1,073 ppm lithium, or 3.387Mt LCE.

The proposed mine would produce an average 27,400 tonnes of LCE a year and have a mine life of +40 years. The mine would be neither a hard-rock mine nor a lithium brine operation, but rather, would process the lithium from claystones in Nevada’s Clayton Valley by leaching the material with dilute sulfuric acid.

Cypress’ Clayton Valley Lithium Project has the size and scalability to interest a large mining company like Albemarle, a major EV automaker like Tesla, or a world-class battery-maker like SK Innovation, developing a large facility in the southern United States. The proof in the pudding for a major taking a serious look at Cypress, will be the mine’s ability to scale up.

To offer this proof, Cyprus is designing a pilot plant capable of continuous production of at least one tonne per day of claystone, for a month. If that test phase is successful, ie., if the flow sheet works and the lithium hydroxide finished product is acceptable, then a potential acquirer could envision 5 tonnes per day, or 20 tpd, whatever production rate is required.

The case for Albemarle reaching out to Cypress to make a deal over its Clayton Valley Lithium Project has strengthened over the past few months.

The chemicals giant has temporarily closed its two lithium facilities in the US, the Silver Peak mine next to Cypress in Nevada, and its Kings Mountain lithium hydroxide plant in North Carolina.

Why is this good for Cypress?

According to Albemarle, the closures are due to weaker demand for lithium, caused in part by the hit to EV sales resulting from the pandemic. The company would restart the idled output in early 2021.

Or would they? Why would Albemarle, a $13 billion market cap company, return to producing lithium carbonate at Silver Peak, then ship it over 2,000 miles to Kings Mountain, NC, when they could purchase Cypress and make lithium hydroxide a short distance from their existing mine, or even at Silver Peak if existing infrastructure is suitable?

There’s no way Silver Peak can produce enough lithium to supply American needs, especially with all of the EV battery and auto production facilities planned.

Moreover, Albemarle’s Silver Peak/ Kings Mountain supply chain is surely not big enough to make a dent in the largest lithium producer in the world’s bottom line.

The company is hurting financially and struggling in Chile, where it battles for market supremacy in the salt flats of the bone-dry, lithium-rich Atacama desert with state-run lithium miner SQM – and now Codelco the state run copper, soon to be lithium, producer.

The lithium giant has been reviewing its expansion plans and stepping back from earlier commitments. A year ago Albemarle postponed a project in Chile that would have added 125,000 tonnes of processing capacity.

Also last year, the Charlotte, NC-based company revised a deal to buy into Australia’s Wodgina lithium mine, owned by Mineral Resources, and said it would delay building a processing plant it expected would add 75,000 tonnes of capacity at Kemerton, Western Australia.

Adding insult to injury, in May Albemarle cut its 2020 budget and tossed its annual forecast, amid the spread of the coronavirus.

It seems to me Albemarle is having a serious re-think of its global lithium business. Why continue a money-losing, lithium-depleted operation in Nevada when its neighbor, Cypress Development Corp, is ready to prove its lithium claystone mining and processing technology on a commercial scale? And why keep butting heads with the government in Chile, when the solution to its expansion dilemma is right next door to its now-shuttered lithium mine in Nevada?

Also consider: in Nevada water rights are granted on a “use it or lose it” basis. Albemarle has the rights to most of the water in the Clayton Valley. If it doesn’t restart Silver Peak, it will lose its water rights. Albemarle has the water, but Cypress has the resource (and the water, with or without Albemarle). A resource that has almost doubled, from 3.3 million tonnes of contained lithium (LCE), to 5.2 million tonnes.

Is this not a partnership waiting to happen?

Now consider, the United States might just be on the cusp of becoming a world leader in electric vehicles and renewable energy, maybe even rivaling China, thanks to Joe Biden’s recent election win.

There are two things that are practically certain once Biden is inaugurated in January and the Democrats regain control of the House, though likely not the Senate.

The first is an avalanche of new spending without limits, as put forward by proponents of Modern Monetary Theory. The second is a huge investment in clean energy projects, similar to Obama’s 2009 plan to electrify the transportation system, of which Biden was a significant architect as vice president. As reported by CNBC,

Biden aims to push as much as $1.7 trillion over 10 years into a plan to boost renewable power and speed introduction of electric vehicles, through tax credits, boosted research and development into technologies including large-scale battery power storage and carbon capture and minimization, and modernizing infrastructure, including the nation’s electricity grid and a nationwide network of public charging stations for EVs.

The Biden campaign has reportedly told US miners it supports boosting production of metals used to make EVS, solar panels and other materials crucial to his climate plan. He also supports bipartisan efforts to build a domestic supply chain for lithium, copper, rare earths and other strategic materials the US currently imports from China and other countries.

In what must be one of the few topics they agree on, in October President Trump signed an executive order that seeks to curb US reliance on “foreign adversaries” for critical minerals including rare earths. It’s interesting to note that Cypress has a unique and potentially lucrative opportunity to mine rare earth elements at its Clayton Valley Lithium Project. REEs were detected in leach solutions ranging from 100 to 200 ppm. The rare earths include scandium, dysprosium and neodymium, in order of economic value.

Cypress ran diagnostic leach tests and determined there is the potential to recover these elements, along with potassium, magnesium and other salts.

Conclusion

Back in 2009, I was one of the first to write about Obama’s electrification plan and what it means for the mining industry. His administration tagged $1.5 billion of the $2.4 billion in electric technology development funds for battery manufacturing projects. Although most of the money was wasted and the plan didn’t get very far, we at AOTH have been advocating for the electrification of the global transportation system ever since, including the mining of battery metals, copper and other raw materials that are crucial to this shift.

The lithium space has been good to us here at AOTH:

- Salares Lithium TSXV:LIT $0.39 to buyout @ Cdn$1.29

- Rodinia Minerals TSXV:RM $0.04 to $0.85

- Lithium-X TSXV:LIX $0.15 to buyout @ Cdn$2.61

If you believe, like I do, that Obama’s electrification plan will be a pale ghost compared to what Biden and his team are planning to do – we are talking the electrification of the American transportation system 2.0 on steroids – then you begin to appreciate why Cypress, sitting there with a couple billion tonnes of lithium in claystone, whose technology is about to be tested on a commercial scale, is so valuable right now.

Yet extremely under-rated by the market. Albemarle, Tesla, and all the other automakers that are already there, making cars in the US, or planning on opening up EV production lines, and battery plants, know the value of having a reliable and scalable supply of lithium, in Nevada, the most mining-friendly jurisdiction in the United States.

In my opinion it’s only a matter of time before a major miner, battery maker or automaker comes along and offers Cypress what it’s worth.

Cypress Development Corp

TSXV:CYP Cdn$0.58 2020.11.13

Shares Outstanding 98,359,470

Market cap Cdn$55.39m

CYP website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Facebook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Richard owns shares of Cypress Development Corp (TSX.V:CYP).

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.