Under the Spotlight – Malcolm Dorsey, CEO Torr Metals

2025.12.11

Rick Mills, Editor/ Publisher, Ahead of the Herd:

Malcolm, you just wrapped up a drill program on the Bertha target. Your model is a New Afton lookalike. And you found a large zone of supergene mineralization. But it’s a strong statement to make modeling after New Afton and supergene.

How do you manage shareholder expectations when it’s something that could literally be so transformative to the hunt for copper and gold in southern BC’s Quesnel Trough?

Malcolm Dorsey, CEO, Torr Metals:

That’s a key point for us. We’re taking a methodical, data-driven approach to how we communicate Bertha.

What we’ve identified so far is a significant zone of supergene-style alteration and mineralization characterized by strong oxidation and weathering that extends to depth. Geologically, that type of supergene profile is something that was also observed in the upper portions of systems like New Afton, and that’s one of the reasons it forms part of our conceptual model.

We’re also seeing mineralization consistent with what we initially observed in the Bertha exploration pit—including native copper and chalcocite. Those are features that, on a purely geological and mineralogical basis, are comparable to what has been described in the literature for deposits like New Gold’s (TSX:NGD) New Afton mine.

At this stage, though, we’re focused on establishing the scale and continuity of the system, not making economic comparisons until we have assays in hand. We’ve drilled along approximately 400 metres of strike, and we’ve intersected the same system down to about 580 metres vertical depth, while also testing the down-plunge extent.

So, our drilling program was deliberately designed to outline the potential geometric scale of the system; strike, dip, and plunge, while pending assays will demonstrate economic potential. In terms of scale, we’ve defined a plunge length that is, in our modelling, about 60% of the plunge length described for New Afton.

To your question on expectations: we manage them by staying conservative in our language, emphasizing that this is early-stage exploration, with no mineral resources or reserves defined on the Kolos Project, and that assay results will ultimately provide the necessary context.

RM: Yes, I studied New Afton and as I have been following the news I’m checking off the boxes I needed to see checked, with some reading between the lines, well done.

MD: What we’re doing is highlighting geological potential based on our observations. The depth and extent of oxidation and weathering we’re seeing at Bertha appear broadly similar, in a conceptual sense, to what has been described for the supergene zone at New Afton.

We are seeing mineralization, but we’re not releasing specific locations or images of mineralized core yet, because we want to present that alongside assays and in context. Assays will tell us what grades are actually present and how they correlate with the geological features we’re observing.

The market appears to understand that we’ve identified a large, coherent system, but the key question — and what everyone is rightly waiting for — is what grades the assays indicate across that system. That’s what will provide meaningful context and help us plan next steps.

So, we are purposefully trying to avoid getting ahead of the data and instead roll out the story in a way that balances geological excitement with appropriate caution.

RM: Something I noticed is that when you did all your surveys, they seem to be remarkably accurate in defining the boundaries. Is that correct?

MD: Yes, the integration between the structural model and the IP geophysics has been very important.

I developed an initial exploration and structural model for Bertha based on mapping and observations at the Bertha exploration pit. That model suggested the main system was located to the south and dipping underneath the pit, which I interpreted to be shear-related with an underlying deeper source.

I then designed and positioned the IP surveys to test that pre-existing structural model, not the other way around. The question was: does the geophysical signature support the structural model we built from surface mapping and pit observations? Too many times, I seen those in industry blindly targeting geophysical anomalies without the appropriate groundwork and the results are predictable.

However, our IP results did indeed match those expectations, which gave us confidence when positioning drill collars and orienting holes. When we drilled, we were testing a geophysical response that we already believed had a solid geological basis. That’s allowed us to effectively test and begin to outline the system in a very targeted way with a relatively modest amount of drilling.

RM: We’ve drilled eight holes. Have we tested the full width and length of this according to the surveys?

MD: We’ve completed eight holes, though one of them, hole 5, had to be abandoned due to a major fault zone we intersected. Even so, the program as a whole has given us a meaningful first pass look at the system.

I believe we’ll come out of this program with a reasonable sense of the potential plunge length, on the order of about 900 metres, which is roughly 60% of the plunge length described for New Afton. It’s important to stress: that is a geometric comparison only, not an assertion of similar grade or tonnage.

There is still room for further growth along strike and down plunge, as the system appears open both at depth and towards the east. The IP surveys indicate that the chargeability anomaly remains open in those directions, so as we expand geophysics and drilling, we’ll be testing those concepts.

I’m planning to expand the IP survey further east in future campaigns to see how far the anomaly continues and to refine our understanding of the full near-surface extent of the system.

RM: When Teck Resources (TSX:T) mined the original New Afton pit, they mined it out and they left. Another company came in, had a different view of things, different model, and they started drilling.

What I want to know is, you said it’s open to depth.

Are our results following the New Afton original open pit with all this supergene and then maybe something underneath it? It took a completely different company and a new look to drill underneath the pit. Are we going to get down there far enough in these surveys to see if we have anything underneath what might be a potential open pit? Can we even talk about that right now?

MD: At this stage, we can say that the geological environment we are seeing remains quite consistent along the strike and plunge we’ve tested.

In terms of depth, a conceptual open pit might be in the range of 250–300 metres vertical depth in some systems, depending on many factors. Our drilling has tested down to about 580 metres vertical depth, significantly beyond a typical conceptual open-pit depth envelope, of course only speaking in terms of dimensions.

The initial holes were designed to test near-surface exposures of the system. The final holes were aimed at testing continuity and depth extent within this supergene-altered environment. Based on that drilling, we see that this environment persists to the maximum depths we have tested so far.

If you look at New Afton purely as a geological analogue, reports suggest the supergene environment was dominant down to roughly 400–500 metres, with transitional “mesogene” and deeper hypogene zones below that. We’ve started testing for potential transitions, but with only eight holes and ~2,700 metres of drilling, this is very much an early-stage geological picture, with first-ever assays to come.

More detailed understanding of grade distribution, geometry, and potential domains of mineralization will require substantially more drilling and, critically, interpretation of the assay results.

RM: Did you see any bornite in the core?

MD: So far, in and around the Bertha exploration pit, the principal copper mineralization we’ve observed includes native copper, chalcocite, and lesser chalcopyrite.

Chalcopyrite often becomes more prominent at deeper levels in this type of porphyry system, particularly toward more hypogene-dominated zones. Hypogene environments are also where you might see more bornite, depending on the system.

At Bertha, we’re still at the stage of characterizing the supergene and transitional environments, and we haven’t yet observed significant bornite in the core. That could change with deeper drilling, but at this point it’s an open question that further work will address.

RM: What else do you want to say?

MD: We’re defining what we interpret as an early-stage hydrothermal–magmatic copper–porphyry system. With a relatively modest program we’ve outlined what the geometry and scale could be, and that speaks to the efficiency of our exploration so far.

Looking ahead, contingent on results, we’re planning roughly 6,000 metres of follow-up drilling, with a goal of returning around late March 2026. That follow-up program would largely look to expand drilling at Bertha, test for possible hypogene-style mineralization in select areas, and focus drilling where assays indicate promising domains of copper and gold.

Of course, all of that is forward-looking and may change based on results.

RM: Have you postponed going to the Sonic Zone?

MD: Bertha will remain our primary focus, reflecting the strength of the geological observations and the scale we’re seeing there.

That said, we have also advanced the Sonic Zone. We’ve collected approximately 1,500 soil samples and a number of rock grab samples from new mineralized outcrops identified during the fall program.

Sonic is characterized by a large copper-in-soil anomaly of roughly 4.5 km², which is already significant in size and highly compelling as a stand-alone project. We expect the new soil lines, including those over newly identified mineralized outcrops, will help us better delineate the potential expanded size and internal patterns of this anomaly and aid in vectoring toward the potential core of the system using geochemical pathfinders.

Depending on results, we may undertake IP geophysics at Sonic, potentially in parallel with drilling at Bertha, to further refine targets. Any drilling at Sonic would likely start modestly, with an emphasis on testing key structural and geochemical targets to demonstrate geological and scale potential of the porphyry system.

Conceptually, if you look at nearby deposits like Ajax, which has been reported as hosting greater than five hundred million tonnes with grades on the order of ~0.5% copper and ~0.4 g/t gold, those provide useful regional geological analogues along the same broader structural trend. But again, mineralization at Ajax is not necessarily indicative of mineralization at Sonic or Kolos, and we must be very clear that we’re still at an early exploration stage.

In addition to Bertha and Sonic, the latter undrilled, we have two other compelling copper–gold porphyry targets on the Kolos Project that have yet to be drilled. Those targets provide optionality for future work programs as we prioritize capital and results.

RM: Absolutely. When we started talking, we talked about the picrite boundary and it’s folded and it’s impermeable. The mineralization hits it, and because it’s high iron, it causes the mineralization to drop out.

Now, I want to get into shattered picrite. How does the picrite shatter and how does it get spread through the deposit? And because it’s a piece floating does the whole boundary of that piece of shattered picrite act like the picrite boundary. Does it cause the mineralization, the copper and the gold to drop out all around the edges of that shattered picrite? How does that work, a piece of shattered picrite?

MD: Our working model is that you have picrite in contact with Late Triassic Nicola Group volcanics, with structural conduits, likely east–west trending zones at depth, that act as pathways for intrusive bodies and hydrothermal fluids.

As intrusions ascend along these contacts or structural conduits, they can generate immense pressure and cause shattering and brecciation of the surrounding rocks. As a result along these contact zones, you end up with large fragments of picrite mixed with intrusive and volcanic rocks in a strongly fractured, permeable zone

.In a supergene setting, oxidizing fluids can percolate through that fractured zone to significant depth, leaching copper from sulphides such as chalcopyrite. When those copper-bearing fluids encounter the iron-rich picrite, you can get strong redox reactions that lead to precipitation of native copper along the margins of those picrite fragments and contacts registering as a chargeability anomaly.

So, each fragment of picrite within the brecciated zone can, in principle, act as a chemically reactive boundary, similar to a larger continuous picrite unit, providing sites for copper to drop out as native copper. This kind of shattered, permeable, reactive environment has been described in early work on systems like New Afton, which again helps inform our conceptual model; but at this stage we are not implying grades without assays.

RM: I did read that from my research. More surface area for the iron to reduce, right, and we have exactly that?

MD: Exactly that. More opportunity to get native copper.

RM: When we start getting news, it’s going to be assays, how do you plan on releasing it? I mean, we’re getting started pretty close to Christmas. Have we got a timeline or a deadline before you’re just going to say, no, hold it, we’re going to wait for the new year?

MD: Assay timing is largely driven by the labs and their workloads. Ideally, we like to receive results in batches that allow us to interpret more than just a single hole at a time, so we can start building a coherent picture.

If results arrive very close to the holiday season, we might consider waiting until early in the new year to release them. That way, investors can more easily follow and digest the news, and we can present the data alongside appropriate geological interpretation.

RM: I agree with that, basically Vancouver kind of shuts down on the 15th and, most people are concerned with family and the holidays, maybe this year might even be a little bit earlier.

MD: Yes, certainly.

RM: So, we don’t do native copper pictures. We don’t do visible gold. It’s actually kind of dangerous putting out pictures of native copper. And visible gold as well. Why is that?

MD: When I’ve seen this done in early-stage exploration it is obvious that publishing selective photos of core can create a distorted view of a system if not accompanied by full context and assays. It’s natural to choose the most visually impressive sections, but they may not represent the broader picture.

I prefer to release photos together with assays, so that investors can see what interval ran, what it looks like in core, and how that fits into the broader geological model.

In supergene environments like the one we’re interpreting at Bertha, visible gold is not something we expect to see commonly, and copper may present as very visible native copper replacing mafic minerals or concentrated in breccias and veins or as being fine-grained and disseminated which is difficult to ascertain by eye. Some of the most important intervals may not “look spectacular” to a non-geologist.

By waiting for assays, we can avoid undue speculation on visible mineralization and present a more serious and balanced picture of the system’s real potential.

RM: Native copper isn’t exactly common in BC. Just to have the New Afton model that we’re working off and to have native copper in a supergene situation, it really is intriguing.

MD: I think it’ll definitely be something that a lot of people will be quite keen to see. You do not see native copper really in any other, at least not in a high degree of abundance, porphyry system in British Columbia. New Afton is quite unique for that, with the abundance of native copper in the supergene zone.

So, I’d say that’s something as well to keep an eye on, looking for that abundance in native copper. That is what we’re targeting here with the supergene zone. So, it’s quite exciting when you see it.

RM: New Afton, when they talk about native copper, they’re talking about 0.5, but I can’t figure out whether it’s percent or weight. How are they measuring that 0.5 copper in order to call it native copper? Because if it was less than 0.5, they wouldn’t even talk about it. The only time they talked about native copper was when they knew it was 0.5. How did they figure out it was 0.5 copper? Is that percent? Is it weight? What is that?

MD: I’m familiar with that part of the text. It’s difficult wording that they chose. I am assuming that what they are actually discussing is the abundance of native copper in the section that was core-logged. So, when you’re looking at it, however they’re breaking up the interval, they’re counting it as 0.5% native copper.

RM: If you tell me there’s 1% copper, I know there’s 22 pounds per ton.

MD: I know that approximately 3 km to the southeast on the Bertha property, there’s the Des occurrence. Its one of the few areas where a little bit of drilling was done back in 1989, approximately 2000 metres.

From this they do report intersecting strongly oxidized zones with narrow native copper intervals grading up to 2%.

RM: That’s interesting. How come you were holding that back?

MD: It’s something that I had to get verified as records are not highly detailed. That was something that we looked at in the field. We were able to find some of the core. Unfortunately, the core is in very poor condition.

We plan to return to fully assess. Unfortunately, most of what we have found is in too poor a condition to re-log or re-assay. It’s been sitting out in the field for a very long time and was pillaged quite a bit likely by, I think, people who had been passing through the area.

RM: They only drilled that one spot?

DM: The Des occurrence is one of the only porphyry target areas that has been historically drilled.

The rest of the drilling was over on the Plug and Meadow Creek epithermal old silver occurrences. Over there was about 2,500 meters or so of drilling. But those are discrete, high-grade gold-silver systems that I believe to be related to the Sonic Zone that is located just to the east of them as the potential source of those shear vein gold-silver systems.

RM: Yes, the copper drops out, then gold, and the silver comes up most distal to these intrusives, usually.

DM: Yes, I like to use it as an alkalic porphyry vector. I see those as being potentially distal to a porphyry source, likely related to the Sonic Zone to the east.

In many porphyry districts, high-grade gold–silver veins can form distal “smoke” to a larger porphyry “fire.” That’s how I view Plug and Meadow Creek, as vectoring tools rather than the primary target. Again, this is a geological interpretation that we will continue to test with data.

RM: Just in terms of managing shareholder expectations. How do you talk up your story among retail investors without being too pumpy? Are people going to understand supergene mineralization, how important the New Afton model is?

MD: Supergene systems can be less intuitive to non-technical audiences, especially when the oxidation profile extends to depths of 500 metres or more, which is somewhat unusual and points to strong fracturing and permeability.

What I am trying to emphasize is that we are seeing consistent geological features through drilling. Historical production from the Bertha pit reported 30 tonnes at 2.14% copper, useful geologic context, though obviously tiny volume and not indicative of any broader grade but in-line with what historical native copper intervals have reported on the property such as at the Des occurrence.

At New Afton, the reported supergene zone produced roughly 23 million tonnes at 0.9% Cu and 0.6 g/t Au, with gold being highly variable in that environment as compared to the more consistent hypogene zone.

Those numbers help frame what supergene systems can look like in principle, but at this early stage they do not mean Kolos or Bertha will achieve similar grades or tonnages.

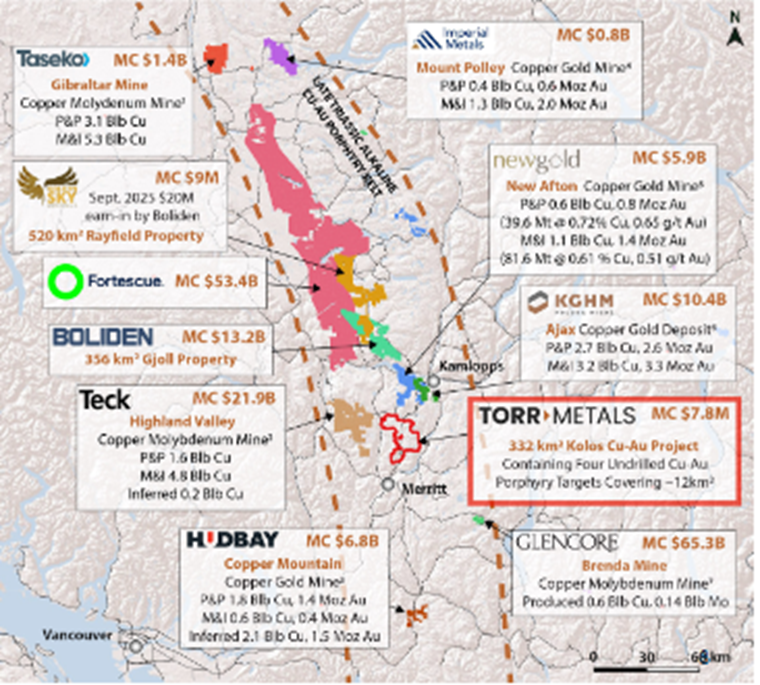

That’s exactly what near-term pending assays and further drilling must determine. For investors, the key message is that we’re in Canada’s most prolific copper producing belt where majors are the most active and concentrated in British Columbia, there will be a near-term need for feed and few if any options with existing deposits, we’re systematically building and testing a geological model for a brand-new porphyry discovery with strong geological analogues to the nearby New Afton mine, and assays will drive how we prioritize follow-up.

RM: Well, the average porphyry grade in BC is roughly 0.4% CuEq, 2% copper in BC is outstanding.

MD: Grades of that magnitude would certainly be phenomenal. In terms of context, publicly available information for systems such as New Afton reports a supergene zone averaging approximately 0.9% copper and 0.6 g/t gold. We reference those numbers only to help illustrate the range of grades that can occur in that alkalic porphyry system; however, mineralization at New Afton is not necessarily indicative of mineralization on the Kolos Project.

Because Bertha is still at a very early stage, with assays pending, it would be premature to speculate on potential grades. Once assays are received, we will have a clearer sense of what the actual grade distribution looks like.

RM: What if anything does the Iron Mask Batholith have with feeding Bertha? I mean, it was responsible for feeding New Afton. It was responsible for feeding Ajax. Are we somehow connected to that batholith, or is this something different or new? Have we tapped into something maybe a little off track, a little off the beaten path, or is this basically just an extension of the Iron Mask?

MD: The Iron Mask Batholith is a Late Triassic–Early Jurassic polyphase intrusive complex, roughly 190–205 Ma, with compositions ranging from diorite to monzonite to syenite. It forms the magmatic and structural framework for deposits like New Afton and Ajax.

Historically, the Iron Mask trend has been seen as northwest–southeast, but many of these structures may be transverse features developed off an older north–south structural fabric. One such structure, known as the Fanta Fault, trends through the eastern part of the Kolos Project near our Kirby and Lodi targets.

Our interpretation is that this older structural control helps localize intrusions and mineralization along a north–south corridor, with northwest-trending structures creating dilational zones where intrusions can ascend. The Kolos Project was staked with that symmetry in mind — looking south of New Afton and Ajax along that broader structural trend.

A BC Geological Survey study in the area has identified intrusive rocks on our property with ages that fall within the Iron Mask range, and compositional work we’ve done at Lodi and Kirby suggests intrusives comparable in composition to Iron Mask-type intrusions.

So, geologically, we believe we’re in a similar magmatic–structural setting, which supports using New Afton and Ajax as conceptual analogues. However, we must stress that mineralization at those deposits is not necessarily indicative of what may be found on the Kolos Project.

RM: Well, I believe the model you’re working from is slowly, but surely, being proven correct.

MD: My master’s thesis was structural and looking at large-scale tectonics and tectonic controls and distribution of mineralizing systems in southern BC. I’ve incorporated a lot of my personal concepts as well as those developed by the substantial academic and industry research done in the region. We will do some geochronology in future but right now, what we need to first demonstrate is do we that there is have economically viable copper potential. But we know compositionally we look a lot like Iron Mask.

RM: We’ve got gold, silver and copper all hitting highs at the same time. What’s your take on that? What’s going on?

MD: In terms of copper, I think people are becoming more aware, as we all have, that there is an impending crisis. All it takes is one major copper mine in the world to get shut down, and suddenly we’re looking at deficits. So really, together with the idea of electrification, you have new technologies, such as AI, that are going to be putting strains on the current copper supply.

So, we do need, not just in terms of technology, but even our current ongoing need for copper. We need to find more is the obvious answer.

In terms of gold and silver, you’re looking at people I think, asking questions about the current financial system, exactly how it is propped up, how it operates, and they’re seeing gold as a good measure of wealth preservation and investment.

People are looking around and realizing as well that in terms of new discoveries, whether you’re in copper or gold, new major discoveries have really dropped off a cliff. And I think that’s been really over-focused by industry on looking at going back to old brownfield projects, projects that have been gone and people have returned to for multiple cycles over multiple decades. So, it’s also really a supply issue as well.

It’s people looking at realizing that there are no new major discoveries. There’s dwindling supplies of all these commodities. There’s increasing demand, whether it’s geopolitical or financial, or in case of copper, just strains on our current infrastructure.

And they’re realizing that we have to find more. So, it’s supply and demand. There’s not much supply to go out there, but rising demand seems like a good thing to be investing in at this time.

RM: It’s really strange that with copper at $5.20 a pound and gold at $4,200 and silver at $60, you think about the timelines of putting a mine into production in North America. The US, there’s a study done, the US has the second longest timeline and Canada is up there and approaching 20 years from discovery to production.

So, you start thinking about that, and then you start thinking that copper, gold, and silver, the demand for them is no longer met by mine supply. It’s only by recycling. And then Tavi Costa, he said with all that’s happened, you would think that the money spent on mining and building mines would be going up, you would not think it’d be depressed but aggregate capex is at one of its lowest levels in history. It’s 90% lower than its previous highs.

We’re nowhere near a top in any of this, and it is structural, isn’t it?

MD: Oh, definitely.

RM: I look at this and I see copper and I see gold, and if you can get both of them in one deposit, you’ve got merger and acquisition increasing because it seems the miners don’t want to spend building new mines. They’d rather eat each other to increase their mining reserves, but of course that does nothing to increase global reserves.

And when the copper analysts talk about copper supply it’s a global number, it does not take into account most of that global production goes to China, South Korea and Japan, leaving little for the west, and that total is getting smaller. So, if you’ve got all that happening, perhaps we’re in the right spot.

MD: And I think you’re seeing that, even with major miners who historically have been very gold-focused, such as Barrick Mining (TSX:ABX), they’ve been reinforcing the fact that what they’re becoming increasingly interested in are copper-gold-alkalic-porphyry systems, simply because of that fact that it can deliver both gold and copper.

Something very unique with BC alkalic-copper-gold systems is just how gold-rich they can be as well. I like to say that many of the times there’s as much a gold deposit as they are a copper deposit. Even when you’re looking at something like Ajax, 3 billion pounds of copper, 3 million ounces of gold.

New Afton, 2 billion pounds of copper, 2 million ounces of gold. So, I think you’re going to see that with the majors, that they’re going to be looking for these systems that deliver both those commodities. And you see that with the focus here in southern BC.

So of course, at the top of their list is infrastructure. They want areas that have the mining infrastructure, the provincial infrastructure. Then they start looking at the prospectivity.

And then they start looking towards this diversification, so copper and gold and porphyry. You see that where I am located with the Kolos Project, there’s currently eight majors. One mid-tier producer with New Gold.

Of course, Coeur Mining (NYSE:CDE) just put in a $7 billion offer on New Gold as well, which holds the New Afton deposit and the Rainy River gold mine in the Dryden District in northern Ontario. So, I think you’re seeing this interest level of guys who’ve done a lot of gold focus.

Even they are starting to enter in the game of where there’s copper and gold, which is just going to add more players coming into areas where there’s fewer and fewer projects to work with and very few brand-new discoveries.

Although at a very early stage the Kolos Project is situated within this broader context, and I see that as a favourable backdrop for our exploration efforts.

RM: Yes, and in our area too, very close, Kodiak Copper (TSX.V:KDK) just came out with the second part of their resource estimate, and it looks attractive.

So, we’ve got news coming out of this area that would be very, very interesting to a major.

MD: Oh, definitely. And I think you see that as well with even new majors.

There was Fortescue and Boliden moved in. That would have been, at this time, I’d say maybe a year and a half, two years ago now. Interesting to see that two major mining companies coming from opposite sides of the world decide that southern BC around Kamloops is the place to go to find a new copper-gold porphyry system.

So, you’re seeing new players move into the region with that. You’re seeing already major established players such as Teck to our west with Highland Valley, Canada’s largest open-pit gold mine. And then you have Hudbay Minerals (TSX:HBM) as well, 100 kilometers to the south at Copper Mountain.

And in between Copper Mountain and us, of course, is Kodiak with the MPD Project.

This doesn’t guarantee any particular outcome for Torr Metals, of course, but it reinforces the idea that southern BC is a focus area for companies looking for copper–gold porphyry opportunities.

RM: Exactly. I’m reading a book called ‘Red, Metal, Blue Planet’, it’s an interesting book.

It talks about copper and innovation and stuff. But the basic thing is there’s a lot of people in the world who live in developing economies. And as an example, the stats say that by 2050, one out of four people in the world will be African.

That’s a lot of room for development there and in India, say. And as a country develops, it’s more copper usage. So, what you do, though, if you look at the two facets of this, you look at more people in the world, all right, that want what we have — air conditioning, automobiles, electronics, all of that stuff, they want what we have.

And that requires more copper for more people. But there’s another aspect to this that people aren’t understanding. It’s that the other side of the equation is more copper per person because of the digital revolution that basically started in the ‘90s.

And you’ve got each new electronic device and data infrastructure to support it like you were talking about. You’ve got robotics and 5G and data centers and AI and new power infrastructure. You’ve got industrialization and urbanization.

And this is copper per person. So, you need more copper per person. You’re also getting more people. And this is driving what the author believes is a strong super cycle for copper. But the problem is, the low-hanging fruit’s been picked. It’s very hard to get a large new discovery of over 200,000 tonnes a year.

And grades are declining. The mineralogy is more complicated, which makes for more expensive metallurgy, the extraction. And so, everything is pointing, I believe, into a super cycle for at least copper.

And when you look at the US dollar and the way things are going, commodities could actually be the last safe haven standing. And copper certainly ranks as in the top of that to me anyway.

MD: Oh, certainly. There are just so many factors looking towards future development. Like you said, even if we just boil it down to grid expansion, looking at the demand of how much copper per person, it’s increasing. We’re going to need more of it as we go forward.

So, with that, it is looking towards, well, where can we get a hold of more of it? And I think going back, like there’s always going to be room to go back to some of these old established projects, seeing if you can scrape a few more pounds of copper out of them. But we are going to need new discoveries. New discoveries really have disappeared in the last 20 years especially.

So, if we do start seeing a new generation of copper discoveries, I think that’s going to be very exciting. And that’s something that I’m looking to do here with Torr Metals (TSX.V:TMET) is to really be a key player in that movement.

RM: Yeah, and that’s copper. And in gold, there’s increasing demand as well for almost the same thing. When you think about it, gold in electronics is growing exponentially per year because of basically the boom in artificial intelligence. You’ve got 5G. You’ve got AI. You’ve got robotics. And of course, the high-performance computing, chips. And a lot of people don’t understand that you absolutely need gold in those high-performance processors and chips.

Like when you get into the high-bandwidth memory, the HBM stuff and all the sensors. You have to use gold for the reliable high-speed connections. AI servers and data centers, they’re huge, significant consumers of high-end gold and printed circuit boards.

You’ve got advanced wireless infrastructure, the automotive and aerospace applications. And of course, you’ve got a consumer economics rebound that is starting. So, the demand for gold is also growing.

And I think that’s why I say that copper and gold really is a space that investors and speculators should be looking at now.

MD: I’m in agreement there.

RM: Okay. Is there anything you want to say to wrap this up, Malcolm?

MD: I’d summarize it this way. We’ve identified what we interpret as a large-scale copper–gold porphyry system at Bertha, with a significant supergene-style environment that appears to be continuous over substantial strike and depth in drilling.

We are awaiting assay results, which will be critical to understanding grade and distribution and to refining our geological model.

We’re also advancing Sonic and other targets on the Kolos Project, which provide additional discovery potential in a region already known for major copper–gold deposits, although our main focus remains at Bertha.

Our approach is systematic, technically driven exploration, with clear communication of both potential and risk. Ultimately, it will be the data that determines how this story develops.

RM: And we are fully funded; we’re not looking to finance before drilling more meters at Bertha.

MD: Correct. Our priority at this stage is to receive the assay results, interpret them within the geological model, and then outline the appropriate follow-up work. The initial 3,000 metres of drilling have helped us better understand the geometry and mineralization of the Bertha system, including a plunge length that appears to extend for more than 900 metres based on current drilling. As we evaluate and disseminate those results for the market to digest, we will use that information to design the next phase of drilling of 6000 meters, which as you say is fully funded with no need to finance in the near-term.

RM: All right, great. We’ll talk again soon.

MD: Sounds good. Thanks Rick.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Subscribe to AOTH’s free newsletter

This interview includes forward-looking information within the meaning of applicable Canadian securities legislation, including statements regarding exploration plans, future drilling, potential mineralization, geological interpretations, assay expectations, potential resources, timing of results, regional activity, and market conditions for copper, gold, and silver.

Forward-looking information is based on assumptions and involves known and unknown risks and uncertainties that may cause actual results to differ materially. These risks include, but are not limited to: exploration, permitting, environmental, financing, commodity price and market risks, as well as those described in Torr Metals’ public disclosure documents available under its profile on SEDAR+. There can be no assurance that exploration will result in the definition of mineral resources or reserves, or that any future economic studies will be positive.

Any references to other deposits or operations (including New Afton, Ajax, MPD, Highland Valley, Copper Mountain, and others) are provided for geological context only. Mineralization on adjacent or similar properties is not necessarily indicative of mineralization on the Kolos Project.

The Kolos Copper–Gold Project is at an early exploration stage, and no mineral resources or mineral reserves have been defined on the project.

Historical results referenced in this interview, including at the Bertha pit and Dez occurrence, are historical in nature, have not been independently verified by Torr Metals, may not be reliable, and should not be relied upon as current.

Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on forward-looking information. Torr Metals undertakes no obligation to update any forward-looking statements except as required by applicable law.

Richard owns shares of Torr Metals (TSX.V:TMET). TMET is a paid advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com This article is issued on behalf of TMET

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.