Transformative year for Max Resources

2022.02.16

In exploration, a number of techniques are employed to gather information about what lies beneath the surface expressions of a potential mineral deposit, prior to drilling. They include mapping, soil sampling, rock chip/ channel sampling, geochemical surveys and aerial geophysical surveys.

Drilling is the final and most important exploration step, usually undertaken after the completion of one or more of the above. Not only does drilling bring up core that is cut and assayed, to ascertain the grades and widths of the mineralization, it also reveals the orientation of the potential orebody (flat-lying, down-dipping, etc.) and allows the exploration company to identify and follow the mineralized structures.

The end goal, of course, is to drill out enough of the orebody to compile a resource, that can be economically mined. This is why investors pay such close attention to drilling, as it usually holds the key to unlocking a project’s potential. Mining properties, and companies, live or die on what a drill finds, which is why it is often referred to as “the truth machine”.

Investors’ interest is piqued when they hear a mining property has mineralization at surface, because it could mean the project is open-pittable, which is cheaper than underground mining. However, what they really want to know, is that surface mineralization extends to depth, and laterally. When this is proven, a mining property transitions from the “discovery” phase to the “development” phase. This is also when speculative capital is replaced by “more serious” investors who visualize a potential path to production. For the junior resource company, it is one of the most exciting stages in its life, often coinciding with a significant bump in the stock price, commensurate with the company’s higher value based on the amount of metal shown to be in the ground that it controls.

Max Resource Corp (TSXV:MXR; OTC:MXROF; Frankfurt:M1D2) is making a critical transition at its CESAR copper-silver project in northeastern Colombia.

After two years of vigorously surface-sampling mineralized outcrops, Max preparing to drill the property, considered prospective for hosting a world-class Cu-Ag resource.

On Jan. 12, Max announced that it has been granted 15 additional mining concession contracts for its project in northeastern Colombia, representing a continuation of last year’s exploration success.

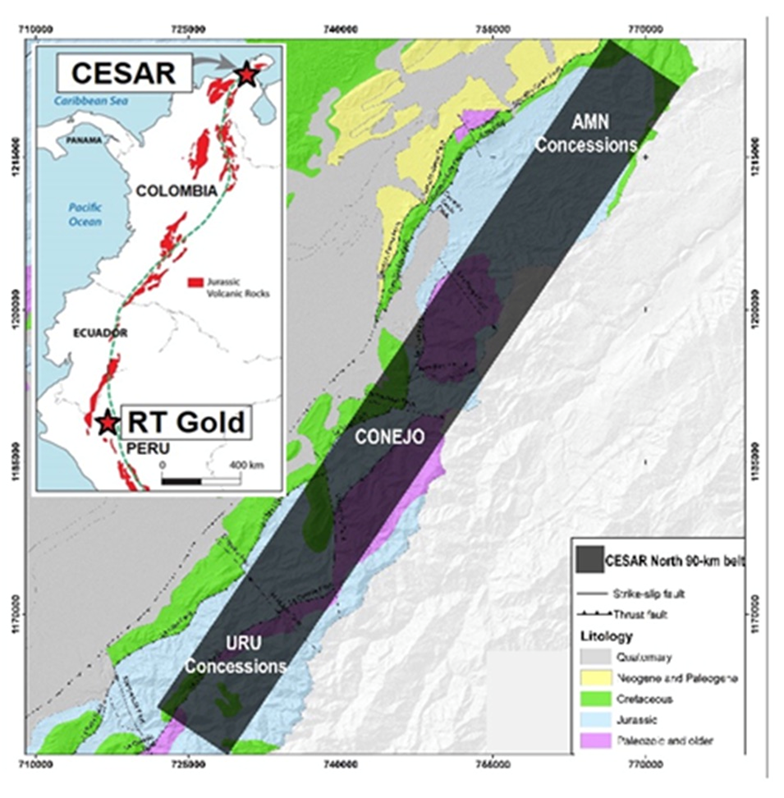

The company now has access to a total of 19 mining concessions covering 186 km², representing the largest area for copper in the prolific Cesar sedimentary basin. These concessions are all located along the CESAR North 90-km copper-silver belt, extending for at least 45 km.

The 19 mining concessions are more than any other company has received in Colombia. Additional concessions are pending.

For Max, this significant milestone forges the way for drill permitting at both the URU and AM drill targets this year; URU is a new discovery that spans 48 km² over a major structural corridor and remains open in all directions, while AM is a 2020 discovery zone spanning 29 km², with highlight grade values of 34.4% copper and 230 g/t silver.

“URU is to be the first significant drilling event on this previously unrecognized copper-silver belt, since the discovery of Cerrejón, the largest coal mine in South America and the reasons for much of the critical infrastructure in the CESAR basin,” Matich commented on the company’s upcoming drilling.

“Located arguably in Colombia’s most prolific mining district, Max’s 2022 exploration and drilling programs are focused on unlocking the true district-scale potential of its CESAR copper-silver project,” he added.

To assist the drill design and exploration at URU, the company is conducting a 290 km² LiDAR survey over five prospective areas spread along 15 km of strike. The goal is to determine high-probability drill targets within the URU zone.

It is interesting to recount Max’s progress in obtaining approvals for its mining concession applications; in Colombia, no mining happens unless these approvals are granted.

Obtaining concessions

In early 2021 Max set about staking land in the region and applying for mining concessions. In deciding whether to approve an application, the Mines Department will determine if there is forestry happening there, whether there is conflict with indigenous groups, and whether there is agreement from the local community, or communities, affected.

Before approval, a public meeting with the community is held. Generally the Mines Department will not even bother to hold a meeting unless they think the answer to mining will be “yes”. To gauge the level of support, the department will communicate with the municipality and put up notices informing locals of the proposed development. After a mining-positive public hearing, it is typically only a matter of weeks before a concession is approved.

Unlike in other countries, where exploration and mining permits are required at each step of the development process, in Colombia the mining concession is all-encompassing. That means it goes all the way from exploration to mining, with each concession good for 30 years, after which another 30-year extension may be granted. Also unlike other jurisdictions, there is no exploration expenditure commitment. A company is required to file an exploration plan but they are not bound by it. That is good news for an explorer because it means they can take a hiatus from “boots on the ground exploration”, say to fly a geophysical survey or to review drill results.

Another bonus: application fees aren’t due until a mining concession is granted.

In Max’s case there were no conflicts with forestry or indigenous, and public hearings were held at communities close to the URU and AM drill target areas. It only took a few months for the Mines Department to approve all 19 concessions, in November 2021.

This successful, and fast application process compares to other companies that have encountered difficulties and delays in getting their mining concession applications approved.

The positive local reception is mostly due to the area Max is working in. The Cerrejon coal mine, located in southeastern Guajira department, is one of the largest open-pit mines in South America and the continent’s biggest coal pit. Local populations understand the kind of footprint and infrastructure that accompanies a bulk-mining operation, including dust and noise. There is also oil and gas drilling in the Cesar basin.

Local municipalities appreciate how their bread is buttered; the bulk of their revenue comes from mining royalties, that help pay for everything from roads to schools to hospitals.

Finally, locals have likely heard about the country’s desire to reduce its dependence on oil and gas exports as it shifts to clean energy. Gustavo Petro, the leftist presidential front-runner in the May 2022 election, has vowed to stop awarding oil exploration contracts, and has said that Colombia needs to leave 80% of its coal reserves underground if it wants to fulfill a global pledge to keep warming below 1.5 degrees C.

The former Bogota mayor and guerilla wants coal-producing states La Guajira and Cesar to expand solar and wind projects, for which copper and silver are necessary metals.

Minimal security concerns

A 2016 peace agreement between the government and the largest Marxist rebel group has stabilized the South American country and opened it up to foreign investment. This has allowed Colombia to explore for minerals in previously inaccessible areas.

And while the illegal drug trade sullied Colombia’s reputation in the 1980s and ‘90s, the actions of the Colombian National Police against drug trafficking have reportedly been so effective, the country has captured and extradited drug lords at a rate of over 100 per year for the last decade.

Though security concerns remain in some parts of the country, they are minimal in the region surrounding the CESAR project. Max has a security manager but no need for a security team.

This is mostly due to the presence of the Colombian army, which is there to patrol the border with Venezuela. The lack of access points for crossing the border has dented the area’s appeal for drug traffickers. In other parts of Colombia, illegal gold mining operations are controlled by drug cartels who use them to launder cash, however the lack of gold in the CESAR basin makes this a non-issue for Max.

In-country team

The company has put together an effective in-country field team, headed by chief geologist Piotr Lutynski and Dr. Chris Grainger, both of whom are on Max’s advisory board.

A senior geologist with over 35 years in the industry, Lutynski has extensive experience in Latin America and Europe, managing and advising companies such as Lumina Gold in Ecuador. His expertise in sediment-hosted copper-silver mineralization came mainly from his work related to the most well-known deposit of this type, Kupferschiefer in Poland.

Dr. Chris Grainger has over 20 years of geological expertise with extensive experience including in Colombia, specializing in grassroots and brownfields exploration. Prior to joining Cordoba Minerals in 2012, Grainger was chief geologist for Colossus Minerals and VP Exploration for Continental Gold, where he helped identify the world-class Buritica gold-silver deposit, that was acquired by Zijin Mining for over $1.4 billion. Grainger has also held senior-level positions at Troy Resources, Lion Ore Australia, INCO Brazil and CVRD Brazil.

Along with Grainger and Lutynski, the Max field team currently comprises nine geologists, all of whom are young, keen graduates from the university at nearby Medellin. Max has made a point of hiring local employees, 31 of which serve on the field, socialization and environmental, logistics, health and safety teams that help communicate the company’s activities to local residents. An important part of their work is handling logistics for organizing site visits through Valledupar, a regional center of about half a million population. The city has all the modern conveniences including an airport, four-star hotels and health facilities. Contractors and consultants typically fly into Bogota, then hop an hour and half flight to Valledupar, where Max picks them up and drops them off at their hotels. From there it’s at most a two-hour drive to CESAR.

Grainger has been involved with Max since the URU and CONEJO discoveries in 2021. His role is essentially to follow up on outcrop discoveries, conferring with head geologist Piotr Lutynski, and instructing the field geologists working beneath them, to determine and carry out next steps.

Another key aspect of Grainger’s work has been bringing visitors on site — many of whom are top of their field in the deposit types found at CESAR — Kupferschiefer and Central African Copper Belt.

According to Max’s CEO Brett Matich, these site visits have been good for Grainger, in that they are giving him confidence about the deposit model Max is following.

“That’s been a huge thing that Grainger talks about, having these experts out there to make sure that what he thinks is happening out there is agreed,” Matich told me over the phone, this week.

The team has forged a good relationship with the Colombian government, and has worked with the National University of Colombia, on research into stratabound copper-silver mineralization within the Cesar basin.

Stratabound game-changer

When Grainger introduced Max’s management to CESAR North, there were two issues: how to determine whether the numerous copper outcrops were isolated or part of a larger mineralized system; and the fact there were few mining concessions available.

The company started with 2,000 hectares and built from there. The game-changer came in late 2019, early 2020, when Max identified the system as stratabound. This was confirmed with the discovery of CONEJO and URU in 2021.

The company has interpreted the sediment-hosted stratabound copper-silver mineralization in the Cesar basin to be analogous to both the Central African Copper Belt (CACB) and the Polish Kupferschiefer deposits. Almost half of the copper known to exist in sediment-hosted deposits is contained in the CACB, including Ivanhoe Mines’ 95-billion-pound Kamoa-Kakula copper deposit in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

However, while the northern part of the 90-km-long CESAR North has been characterized as “Kupferschiefer-style” (copper-shale) mineralization, the southern part containing URU is suspected to be more “Central African” in nature.

The CONEJO zone has a 3.7-km strike, is open in all directions and lies along the CESAR North Kupferschiefer-type sedimentary exhalative (sedex) copper-silver mineralization.

With so much mineralization exposed in surface outcrops, there was no need to do soil sampling, enabling Max to skip a step; rock chip samples would suffice in proving the extent of the mineralization and the grades.

“In relation to exploration we’ve moved pretty quickly,” says Matich. “We could keep going forever [sampling] but we’ve come to the stage where we wanted the mining concessions, so the drilling of it is the next stage of proving up the model.”

Mineralogy is an interesting part of the exploration. With most large copper deposits, the sulfide mineral chalcopyrite is dominant. At CESAR, there has been no chalcopyrite found thus far. In fact the primary copper mineral, that is carrying the higher grades, is chalcocite; this is considered quite unusual.

From numerous site visits, none has been able to cite another sedimentary basin that has chalcocite as the primary copper mineral. The secondary copper mineral is malachite.

The other aspect that makes CESAR stand out from other copper projects is the amount of exposed mineralization; “50% of the copper areas that we went to we didn’t know anything about, it was a matter of going out there, we’d see copper everywhere,” says Matich.

2022 exploration

In 2022, Max looks to continue its exploration success at the CESAR property, moving closer to delineating the true extent of what it believes to be a massive sediment-hosted stratiform copper-silver mineralization comparable to some of the world’s best.

On the company’s itinerary are the following items (in no particular order):

- Exploration to focus on the URU zone;

- Infill mapping and modeling of the LiDAR data;

- 3D drill design and permitting;

- Conduct the first ever drill campaign targeting major copper deposits in the CESAR basin;

- Continue the regional exploration program over the Cesar basin;

- Drill-test AM zone (AMN)

- Receive additional mining concessions to drill CONEJO.

Copper market update

The discoveries made on Max’s CESAR property come at a time when the copper industry is threatened by a looming global supply crisis, as the world needs more of the metal to accelerate its transition towards cleaner energy sources.

Green-related demand will gather pace in the second half of this decade, ultimately generating nearly 5 million tonnes of additional demand, Goldman Sachs recently said.

BloombergNEF estimates that in 20 years, copper miners will need to double the amount of global production — from the current 20 million tonnes annually to 40 million tonnes — just to meet the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles.

This is a tough ask considering some of the world’s largest mines are seeing depleted copper reserves and lower ore grades, so it would be difficult for global production to even maintain a 20Mtpa pace.

Mining and metals consultancy CRU Group estimates that, without new capital investments, global copper mined production will drop below 12Mt by 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15 million tonnes.

According to CRU, there are over 200 copper mines that are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

S&P Global Market Intelligence predicts that a production shortfall of 3.85 million tonnes could happen as early as 2025, due to diminishing supply from existing mines and rising demand for copper concentrates globally.

The solution, as simple as it sounds, is to have more copper projects that can be developed into producing mines.

S&P Global has identified 14 probable and 26 possible projects in the copper pipeline, though the firm admits it’s unlikely that all will come to fruition.

Even should many of these projects come online, they would likely just replace existing copper output and not contribute to supply growth. Therefore, a sustainable copper supply chain to meet future demand requires more discoveries than we’ve seen in recent years.

As of now, the global copper cupboard is quite bare. Over the past decade, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically around the globe, with tonnage from new discoveries falling by 80% since 2010, according to S&P Global.

For 20 million tonnes of additional copper to be delivered by 2040, the world needs the equivalent of one new Escondida mine (1 million tonnes annual production) each year for the next 20 years.

And this task is only going to get more difficult when factoring in events beyond miners’ control. Increasing copper supply is only getting harder as environmental groups and local communities refuse to grant miners “social licence” to operate, and politicians seek a bigger share of industry profits.

More positively, industry analysts are becoming more bullish on commodities, in this era of high inflation, especially metals. (commodities are considered a good hedge against inflation)

The stock market has been volatile lately on an expected interest rate hike from the US Federal Reserve, likely in March. On Thursday it was reported that US consumer prices surged more than expected in January, lifting US CPI to 7.5%, higher than December’s 7% and hitting a fresh 40-year record.

Bloomberg has Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research for Goldman Sachs, declaring copper as “the new oil”, noting it’s absolutely indispensable in global decarbonization strategies with copper shortages already being felt.

Referring to the Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index, which reached a new record earlier this year, driven in part by surging oil prices, Currie said this week he’s never seen commodity markets pricing in the shortages they are right now.

“I’ve been doing this 30 years and I’ve never seen markets like this,” the commodity expert said in a Bloomberg TV interview. “This is a molecule crisis. We’re out of everything, I don’t care if it’s oil, gas, coal, copper, aluminum, you name it we’re out of it.”

As evidence, Currie points to the futures curves in several markets that are trading in “super-backwardation”. Bloomberg points out, All six of the main industrial metals traded on the London Metal Exchange moved into backwardation late last year, in a rare synchronized bout of tightness last seen in 2007.

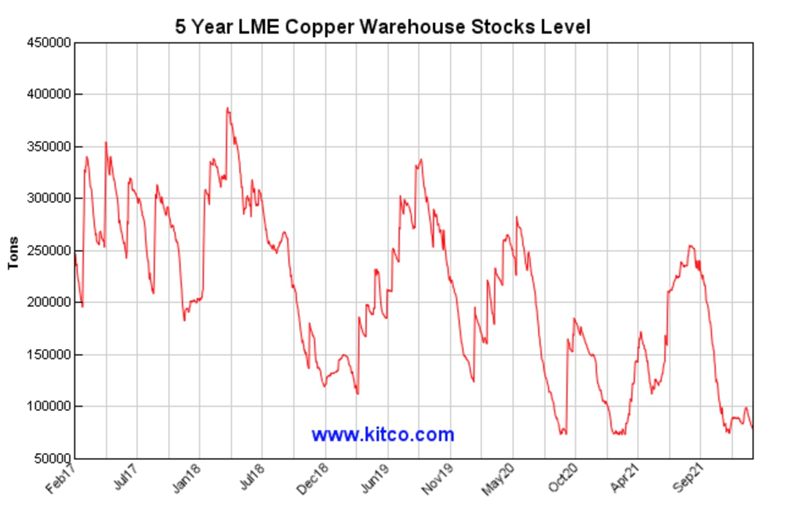

Copper stored in LME, New York and Shanghai Metal Exchange warehouses are once again approaching historically low levels, causing copper prices to spike, in a repeat of the same trend last October, which sent the bellwether metal into record territory. Only about 200,000 tonnes were available Wednesday, not even enough for three days global consumption, as March copper futures hit $4.58 a pound.

Meanwhile the demand side of the equation is strengthening, helped by increased electric-vehicle penetration. According to a joint report from Ernst & Young and Eurelectric, Europe will have 130 million EVs by 2025.

The report’s projections, cited by BNN Bloomberg, show Europe’s EV fleet growing from its current <5 million to 65 million by 2030, then doubling over the following five years. This number of EVS will require 65 million chargers.

EVs take about 85 kg of copper per vehicle.

An EY leader notes it took 10 years to install 400,000 chargers, now we will need about 500,000 per year until 2030, and 1 million every year between 2030 and 2035. Where is all the copper going to come from?

Meanwhile the Biden administration is planning on spending $5 billion over five years to install EV chargers, mostly along interstate highways, with another $2.5B given to rural and under-served communities. The funds are coming from the trillion-dollar infrastructure bill passed by Congress in November.

Conclusion

For the next 5-10 years, we expect the major copper producers to splash the cash on the next batch of copper projects in hopes of keeping supply levels afloat. Higher copper prices during what many consider to be the next “commodity super-cycle” will certainly incentivize bigger investments.

One project to keep an eye on is Max’s CESAR property located conveniently along the prolific Andean Copper Belt in an underexplored region of Colombia. Work to date has shown that the project has both the size and grades for a potential multi-decade copper operation.

So far, Max has managed to identify extensive copper-silver mineralization through rock chip sampling because creeks cut across and expose the multiple horizons for a considerable depth.

Just over a year ago, the company reported that stratabound copper-silver mineralization found at surface, extends for over 400m down dip. An encouraging sign.

At AOTH, we are expecting this year to be transformative for Max. The company has received 19 mining concessions covering 186 km², more than any other Colombia-focused explorer.

Max Resource Corp.

TSXV:MXR; OTC:MXROF; Frankfurt:M1D2

Cdn$0.30 2022.02.10

Shares Outstanding 98.0m

Market cap Cdn$29.4m

MXR website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Richard owns shares of Max Resource Corp. (TSXV:MXR). MXR is a paid advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.