The worsening plight of the global consumer – Richard Mills

2023.02.23

Consumer spending makes up 70% of global GDP. It’s no wonder, therefore, that central banks are so focused on keeping inflation in check: to keep the wheels of economic growth spinning, the gears of the consumer’s spending habits must be greased.

A healthy rate of price increases (inflation), usually 2%, is the goal of the US Federal Reserve and other central banks. The Fed and central banks worldwide have been raising interest rate to quell inflation that in some countries has reached a 40-year-high. And while inflation levels in the aggregate (i.e., the Consumer Price Index) have started to retreat, price categories critical to most consumers, like groceries, gas, rent/ mortgages and electricity, are only getting more expensive.

Meanwhile, high interest rates are also weighing heavily on consumers.

In the first quarter of 2021, interest rates in a sample of 58 rich and emerging economies stood at an average of 2.6%. By the final quarter of 2022, this figure had reached 7.1% (!)

Higher rates, of course, hike the payments on student and car loans, lines of credit, credit cards and mortgages. For the highly leveraged, this can mean hundreds of dollars more a month.

Food insecurity on the rise

High food prices triggered by the war in Ukraine and numerous droughts have driven millions into extreme poverty and malnutrition.

The Global Report on Food Crisis 2022 Mid-Year Update found up to 205 million people are expected to face acute food insecurity and to be in need of urgent assistance in 45 countries.

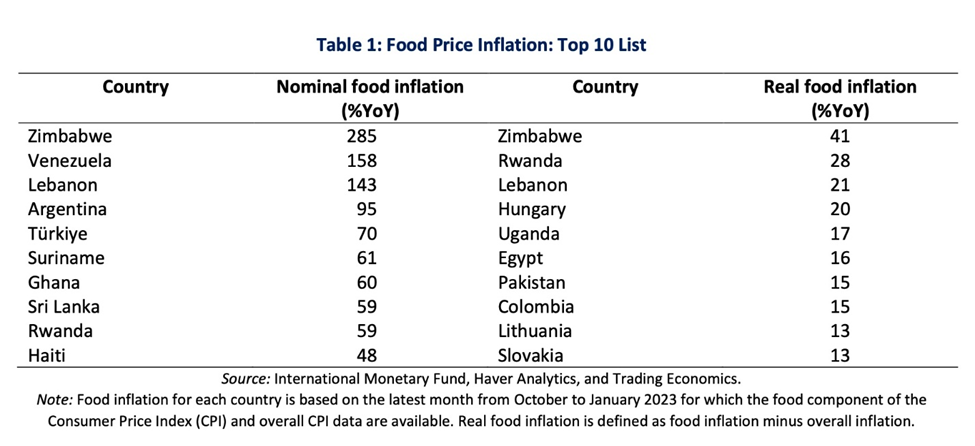

According to the latest World Food Program report, food inflation remains high in almost all low and middle-income countries, and 91% of upper middle income countries are experiencing double-digit inflation. The countries affected most are in Africa, North America, Latin America, South Asia, Central Asia and Europe.

Experts worry that the combination of high fertilizer prices (see below), climate and weather shocks could make a bad situation worse for the most vulnerable.

“I think we will have a food availability problem [in 2023] … If we don’t address the issues that need to be addressed quickly, effectively, strategically — I’m worried that we will have mass destabilization around the planet [this] year,” World Food Programme Executive Director David Beasley told Devex.

David Laborde, senior research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute, said increased rice prices are a concern this year, hit by a double whammy of fertilizer shortages and floods in Pakistan.

Laborde also said rising debt levels are extremely concerning for low- and middle-income countries. Because of a still relatively strong US dollar, many countries are having trouble importing basic staples, and inflation is putting pressure on the poorest households.

“Overall, I am more pessimistic right now than I was in the fall of last year,” he told Devex. “Weather, level of stock, fertilizer, macroeconomic situation with debt crisis and inflation rate … the situation is going to be tense again this year.”

Global food insecurity is being exacerbated by extreme heat. The two are connected because the changing climate “worsens the stability of global food systems,” states the ‘2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels’.

According to the report, in 103 countries analyzed, extreme heat was associated with 98 million more people reporting moderate to severe food insecurity in 2020, compared to what was reported annually between 1981 and 2010.

High temperatures have a negative impact on crop growth, because they cause crops to mature faster, reducing the yield. The report via Global News found that average crop growth season lengths in 2021 have shortened for a number of key staples: the crop growth season for maize is down more than nine days, rice’s growth season is down almost two days, and winter and spring wheat has shaved six days off its growth season.

Reuters admitted recently that the hunger crisis in Africa has become “bigger and more complex than the continent has ever seen.” Considering the number of famines Africa has experienced, that is quite a meaningful statement.

Meanwhile in the Middle East, a severe wheat shortage is forcing Pakistanis to wait in line for hours “to receive a single bag”, while in Australia, a potato shortage has gripped the nation.

One commentary titled, ‘Food shortages are starting to become quite serious all over the planet,’ notes that:

In previous decades, there have been times when there have been localized famines in various parts of the world.

But what we are facing now is global.

According to the New York Times, food shortages are “causing intense pain across Africa, Asia and the Americas”…

“We’re dealing now with a massive food insecurity crisis,” Antony J. Blinken, the U.S. secretary of state, said last month at a summit with African leaders in Washington. “It’s the product of a lot of things, as we all know,” he said, “including Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.”

The food shortages and high prices are causing intense pain across Africa, Asia and the Americas. U.S. officials are especially worried about Afghanistan and Yemen, which have been ravaged by war. Egypt, Lebanon and other big food-importing nations are finding it difficult to pay their debts and other expenses because costs have surged. Even in wealthy countries like the United States and Britain, soaring inflation driven in part by the war’s disruptions has left poorer people without enough to eat.

North American food costs soaring

Canadians have felt the impact of soaring food costs first-hand.

While overall inflation slowed to 5.9% in January, the price of groceries continued to accelerate at a faster pace than December, Statistics Canada reported this week.

The federal agency said grocery prices last month were up a steep 11.4% compared to a year ago, including meat, bakery goods and vegetables. The CBC said Fresh and frozen chicken was especially pricey, rising nine per cent from December — an increase that Statistics Canada attributed to seasonal demand, supply issues and the impacts of avian flu.

As of the first week of January, more than 5 million birds had been culled in Canada, causing supply crunches.

Bird flu has reportedly killed over 58 million chickens and turkeys in the United States. Also, according to Tucker Carlson, hens have suddenly stopped laying eggs, with some farmers concluding their chicken feed may be responsible.

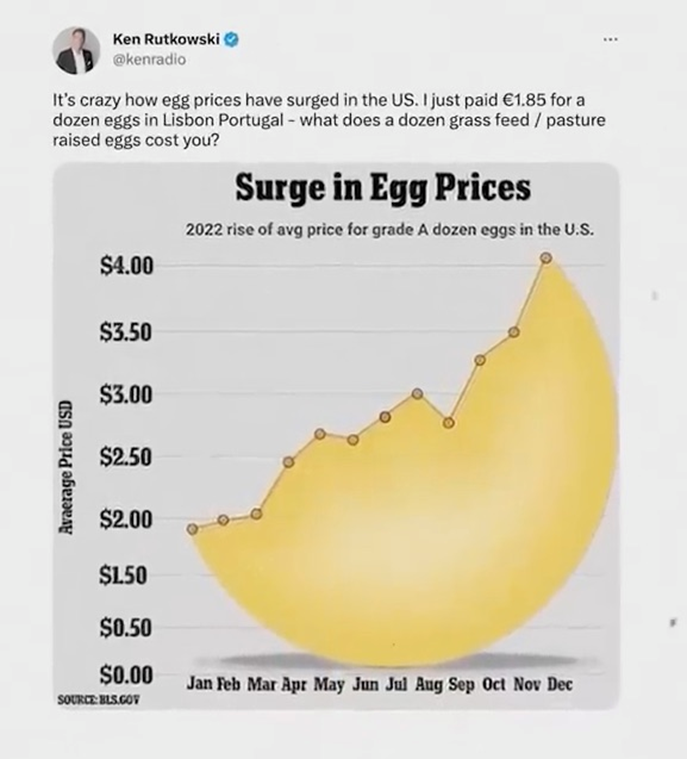

The reluctant egg birds are contributing to massive price spikes; US egg prices were up 59.9% in December (Canadian egg prices are comparably more stable, with “only” a 16.5% rise in the same month. Some say supply management is to thank).

In-depth on Costco’s nation-wide egg shortage

Drought conditions throughout North America, meanwhile, are causing serious problems with cattle production.

An uptick in drought and other extreme weather events has beef producers in the US and Canada thinning their herds in record numbers. (CBC News, Feb. 21, 2023)

The phenomenon requires some explanation. Over the past few years, dry conditions in both countries prompted producers to reduce their herds by sending more cattle to slaughter, resulting in an increased production of beef products, like burgers and steaks. While this would normally drive cattle prices down, inflation and high demand for beef has kept prices elevated.

Less supply in future, owing to thinner herds, will drive prices up further.

A drought in Canada in 2021 meant pastures were reduced and producers had to buy more expensive feed from the US, sending costs higher.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, more than two-thirds of US cattle is in an area affected by drought, leading to the largest contraction of the North American cattle herd in a decade. US producers have contracted their herds three years in a row, resulting in the lowest cow herd on record.

The problem will not only affect the beef industry, but the dairy industry, too. Less cows to milk can only mean higher dairy prices.

Like Canadians, American shoppers are not expected to see much, if any, relief on their grocery bills this year. While US food inflation has been decelerating from an 11.4% peak in August, 2022, groceries were about 10% higher in December than a year earlier.

(The price of orange juice recently hit a new record high due to projections that Florida citrus production will be the lowest since 1945.)

As CBS News noted recently, that makes the timing of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) cuts particularly challenging. More than 30 million Americans face a “hunger cliff” as 32 states are set to slash food-stamp benefits starting in March.

The cuts mean a family of four could see benefits reduced by around $328 per month; elderly Americans could see their SNAP payments fall from $281/mo to as low as $23 (!) The average monthly benefit in 2022 was $230.88.

According to US Department of Agriculture data, despite having the lowest unemployment rate since 1969, more than 42 million Americans remain on food stamps — 6% more than in 2020.

In America, a job may not mean an end to food insecurity. Many SNAP households have such low-paid jobs, that they qualify for benefits.

And the UK, too

On the other side of the Atlantic, a survey by market researcher Kantar found that UK food inflation soared to a record 16.7% in January. Basics such as milk, butter, cheese, eggs and dog food were all more expensive.

The report via RT says that grocery price growth is at its highest since the firm started tracking the figures in 2008, adding nearly £800 ($1,000) to the typical annual shopping bill and forcing households to change their shopping habits to save costs.

“Late last year, we saw the rate of grocery price inflation dip slightly, but that small sign of relief for consumers has been short-lived,” Kantar’s head of retail and consumer insight, Fraser McKevitt, said, noting that the current reading jumped a “staggering” 2.3 percentage points from December’s 14.4%.

The latest increase will take the average annual food shopping bill to £5,504 ($6,781), up £788 ($974), according to Kantar.

The world’s biggest food corporation, Nestle, reportedly said prices for staple food items will continue to grow in 2023, noting the 8.2% it bumped up prices last year was not enough to offset a rise in its own costs, that had substantially dented profits.

Unilever, Coca-Cola, Heineken, Colgate-Palmolive and Procter & Gamble have all flagged further increases in the prices of their goods this year, a news source said.

Fertilizer frenzy

Most of the food we consume comes from the labor of agricultural activities.

The key input in agriculture is fertilizers, which farmers use to supplement natural soil nutrients, antibiotics to prevent animal diseases, and pesticides to protect crops against animals, insects, weeds and various microorganisms. Thus, it should come as no surprise that, if the cost of fertilizers rises, food prices will naturally increase.

Columnist Michael Snyder, from The Economic Collapse, states:

If we suddenly stopped using all fertilizer immediately, we would only be able to feed about half the world.

So the production of fertilizer is absolutely critical.

Unfortunately, almost all of the phosphorus that we use in our fertilizers comes from “non-renewable phosphate rock”, and 85 percent of the remaining supply is located in just five countries: Morocco, China, Egypt, Algeria and South Africa.

Indeed fertilizer, until recently considered a rather bland commodity that few bothered to write about, has become “sexy” — pushing crop nutrients to the forefront of political agendas around the world.

That’s because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has highlighted the role of fertilizers and who controls them as a strategic lever of global influence.

A Feb. 19, 2023 Bloomberg article makes the following points, edited for clarity:

- About 20% of Malawi’s population is projected to face acute food insecurity during the “lean season” through March, making the use of fertilizers to grow crops all the more vital. It’s one of 48 nations in Africa, Asia and Latin America identified by the International Monetary Fund as most at risk from the shock to food and fertilizer costs fanned by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. One year on, the upheaval caused to world fertilizer markets is seen by the UN as a key risk to food availability in 2023.

- Yet alongside humanitarian considerations, it’s the realization that much of the world relies on just a few nations for most of its fertilizers — notably Russia, its ally Belarus and China — that’s ringing alarm bells in global capitals. “The role of fertilizer is as important as the role of seed in the country’s food security,” said Udai Shanker Awasthi, managing director and chief executive officer of the Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative, the country’s largest producer. “If your stomach is full then you can defend your house, you can defend your borders, you can defend your economy.”

- Last year’s jolt to the $250 billion global fertilizer industry highlighted the role of Russia and Belarus as exporters of almost a quarter of all world crop nutrients. While Russia’s agricultural products including the three main types of fertilizer — potash, phosphate and nitrogen — are not targeted by sanctions, exports remain curtailed through a combination of disruptions to ports, shipping, banking and insurance.

- The UN says the core problem lies with shipping insurers unwilling to cover Russian cargoes, and with key agriculture banks being unable to make financial transactions since they are disconnected from SWIFT. The EU and US issued a joint statement in November clarifying that “banks, insurers, shippers, and other actors can continue to bring Russian food and fertilizer to the world.”

- The European Union’s sanctions regime has clogged up trade to such an extent that it’ll have caused a total curtailment of fertilizer shipments by some 13 million tons by the one-year mark of the war on Feb. 24.

- The market disruption triggered a spike in prices last summer that led to stockpiling by those able to afford fertilizers, and while prices have since come down significantly, they remain above pre-pandemic levels. The situation is exacerbated by sanctions on potash giant Belarus alongside the decision by China, a major producer of nitrogen and phosphate fertilizers, to impose restrictions on exports to protect domestic supply, curbs that analysts don’t see being lifted until the middle of 2023 at the earliest.

- Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Alexis Maxwell says that even though prices have fallen more than 50% from last year’s peak, farmers in Southeast Asia and Africa remain exposed. The African Development Bank has warned that curtailed use is likely to mean a 20% drop in food production, while the WFP sees smallholders in the developing world at risk of “a major food availability crisis as the fertilizer crunch, climate shocks and conflict upend food production.”

- The UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization set up a trade tracker last year showing that many net importers in Latin America, eastern Europe and Central Asia depend on Russia for more than 30% of all three main fertilizer ingredients.

- Latin America depends on imports for 83% of fertilizers applied, mostly from Russia, China and Belarus, according to the Washington-based International Food Policy Research Institute.

- The race for fertilizer supplies has spawned efforts to encourage self-sufficiency. In an echo of the Chips Act that made $50 billion available for US semiconductor production, President Joe Biden’s administration has announced $500 million in grants to increase “American-made fertilizer production” and “bring production and jobs back to the United States.”

High potash prices are likely to persist as the world scrambles to bring more production. When the war started, potash for delivery in Brazil, one of the most important markets, quadrupled to USD$1,200 per tonne. While prices have come down to about $500/t, a private potash company chief executive says 2023 will not likely bring relief to a growing global food shortage, as many expect food inflation and rising prices to continue to put our food security at risk. [Matt Simpson] also notes that, given the ongoing turmoil in Russia impacting neighboring Belarus, more than 15 million tonnes of expected new production would probably not come online since those projects won’t likely secure funding because of the heightened risk.

“This sets up the market to remain tighter for longer,” the CEO says.

Tapped out

Consumers around the world are not only being asked to come up with more money to pay for the same basket of goods and services, as a year ago. Also pivotal to what is increasingly becoming a cost-of-living crisis, is the role of higher interest payments.

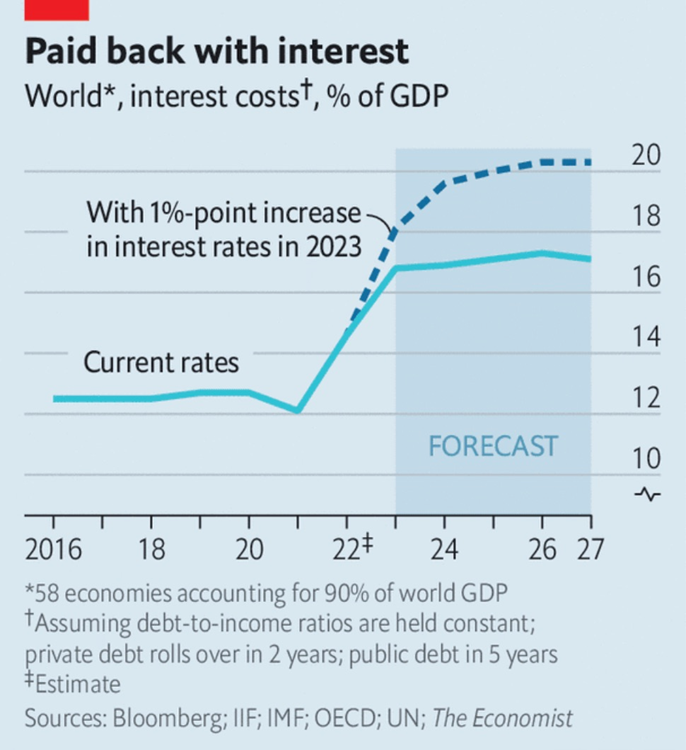

The Economist estimated the interest bill for companies, households and governments across 58 countries, representing over 90% of global GDP, in 2021 amounted to $10.4 trillion, or 12% of combined GDP. By 2022 it had reached $13 trillion, or 14.5% of GDP. A key point is the more indebted the world becomes, the more sensitive it is to interest rate rises.

Take a look at the chart below. The Economist analysis suggests that, if rates follow the path priced into government bond markets, interest costs will reach 17% of GDP by 2027. Just one percentage point above what markets have priced in would bring the bill to 20% of GDP — a level not seen since the Great Recession.

As for what this means for consumers, the analysis found that, When it comes to households, rich democracies, including the Netherlands, New Zealand and Sweden, look more sensitive to rising interest rates. All three have debt levels nearly twice their disposable incomes and have seen short-term government-bond yields rise by more than three percentage points since the end of 2019.

Remember, consumer spending makes up about 70% of the global economy, so high levels of credit card debt, bank loans, student loans, lines of credit, etc., represent a significant danger.

Bloomberg says trouble is brewing most in countries that have a large share of variable-rate mortgages (as opposed to fixed mortgages), and where households have kept adding debt instead of paring it back. The poster-children are South Korea, Australia, and perhaps surprisingly, Canada.

Research from the Bank of Canada found that variable-rate mortgages now account for one-third of outstanding mortgage debt, up from about one-fifth at the end of 2019 (Financial Post, Nov. 22, 2022). Moreover, about half of these mortgages have reached their trigger rate, which is the point where additional payments may be needed. This number represents about 13% of all Canadian mortgages.

The CBC reported this week that Canadian mortgage costs continue to rise, hitting 21.2% in January, as the Bank of Canada tried to tame inflation by bringing its baseline interest rate to a 15-year high of 4.5%.

In fact Canadian households are among the most indebted in the developed world. 2020 household debt in Canada was easily the highest of G7 countries, at 177.3% of disposable income, followed by the UK at 147%. Household debt in the US that year was 101%. Within the 38-member Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Canada ranks ninth in terms of average household debt. (Business Council of Alberta)

Of course it isn’t only households that have been spending now and paying it back later. Corporate debt is also significantly on the rise.

The Economist cited research from S&P Global, that found default rates on European speculative-grade corporate debt rose from under 1% at the start of 2022 to more than 2% by the end of the year. French firms are especially indebted, with a ratio of debt to gross-operating profit of nearly nine, higher than any country bar Luxembourg.

Corporate debt faces a reckoning when it comes to higher interest rates. The Institute of International Finance forecasts that, in an economic downturn as severe as the 2008 financial crisis, $19 trillion in debt would be owed by non-financial firms without the earnings to cover the interest payments. These companies are sometimes referred to as “zombies”.

Conclusion

Despite what you read about inflation decreasing, the reality “on the ground” is quite different. Take the January inflation data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. While prices for a range of goods and services rose by 6.4% over the past 12 months, down slightly from an annual rate of 6.5% in December and a 40-year high of 9.1% in June, on a monthly basis prices increased by 0.5% in January compared with a slower gain of 0.1% in December. The BLS says the acceleration was driven by shelter costs.

“Home prices rose much faster than incomes over the past three years,” Bright MLS Chief Economist Lisa Sturtevant told USA Today. “The Fed’s rate increases, which have led to higher mortgage rates, have made the cost of buying a home even more costly.”

Rental costs have also soared, partly due to homeowners, unable to afford higher mortgage payments, forced to sell and go back to being tenants. According to Credit Karma, from 2017 to 2022, the average year-over-year increase in rent was 5.77% nationwide, with the biggest increase occurring from 2021 to 2022 at 14.07%.

US energy prices have gone up, too. According to the BLS, the energy index rose 8.7% over the past 12 months, driven by fuel oil, electricity and natural gas. While gasoline prices have fallen from a June 2022 peak of $5.10 a gallon, to the current $3.49, fuel oil was 27.7% more expensive, electricity prices rose 11.9%, and the index for natural gas climbed a whopping 26.7%, year on year.

In Canada, the average monthly cost of renting a home surpassed $2,000 for the first time in November. The data via the CBC showed Canadian renters are having to pay an average $2,025 to keep a roof over their heads, up 12.4% since November 2021 and far outpacing Canada’s current inflation rate of 5.9%.

Soaring food inflation, the higher cost to rent or own a home, and heat it, plus all the other categories of goods and services that keep going up, are taking their toll.

And remember, inflation is compounded. 6% inflation in a given month is the amount prices have gone up over the past 12 months. But that is in addition to the inflation of a year ago. Even if last year’s inflation was 3%, that’s a 9% increase over two years.

Combining record-high inflation, food up 11% yoy, energy costs still high and going higher and much higher interest costs on loans, mortgages, credit cards and lines of credit, brings me to the obvious conclusion: 2023 is going to be a very difficult year for the global consumer.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.