The world produces enough food, so why are so many going hungry?

2021.12.07

What does it mean to go hungry? The United Nations says hunger is when populations experience severe food insecurity, meaning they go for days without eating due to lack of money or they are without access to resources.

Another definition is the distress associated with lack of food, where the threshold is below 1,800 calories per day. Many people in the West follow diets trying to limit their food intake by that amount, which shows the frivolity of such “First World problems” compared to the food-deprived.

Hungry people are often under- or malnourished, referring to deficiencies in energy, protein and vitamins or minerals.

Just look at all those hungry mouths we have to feed

Take a look at all the suffering we breed

So many lonely faces scattered all around

Searching for what they need

“Is This The World We Created?”by Queen

Most people believe hunger is caused by food scarcity, however this is wrong. There is currently more than enough food available to feed our global population of 7.9 billion, yet over 800 million still go hungry. How can this be?

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the world farms, grazes or fishes more than 1.5 times enough food to feed a planet populated by 10 billion people, which is the number the UN projects will inhabit the Earth by 2050.

But people making less than $2 a day — most of whom are resource-poor farmers cultivating un-viably small plots of land — cannot afford to buy this food, states an article in the ‘Journal of Sustainable Agriculture’.

In other words, hunger is caused by poverty, not scarcity. More on that below. For now we should point out, only recently has hunger started rising again, after declining for a whole decade.

Before 2019 the world was making significant progress in this regard. The proportion of under-nourished people declined from 15% in 2000-04 to 8.9% in 2019, while the rate of stunting — children too short for their age due to chronic malnutrition — fell from 33% in 2000 to 21.3% in 2019.

Well the world turns

And a hungry little boy with a runny nose

Plays in the street as the cold wind blows

In the ghetto

“In The Ghetto” by Elvis Presley

However from 2019 to 2020, the number of under-nourished grew to 161 million, largely driven by conflict, climate change and the covid-19 pandemic, states Action Against Hunger.

Nearly 10% were estimated to be under-nourished last year compared to 8.4% in 2019.

The UN agrees there was a significant worsening of hunger due primarily to covid, with a multi-agency report estimating up to 811 million people, around 10% of the global population, were under-nourished in 2020.

“Unfortunately, the pandemic continues to expose weaknesses in our food systems, which threaten the lives and livelihoods of people around the world,” the heads of five UN agencies wrote in ‘The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World’, the first global assessment of its kind in the pandemic era.

Over half of the under-nourished live in Asia, a third are in Africa, with the balance living in Latin America and the Caribbean. The report notes the sharpest rise in hunger was in Africa, where the prevalence of under-nourishment in the population, @ 21%, is more than double any other region.

Overall around 30% of the global population, or 2.3 billion people, lack access to adequate food; the presence of moderate to severe food insecurity rose as much in one year as the past five years combined.

As far as malnutrition, in 2020 over 149 million children under five were estimated to have been stunted, over 45 million were too thin for their height, and fully 3 billion adults plus children were locked out of healthy diets due to excessive costs.

The numbers especially when considered from a Western perspective are saddening, however we need to appreciate the role that science and technology has had in reducing hunger, improving agriculture and growing human populations.

The Green Revolution

The modernization of the global agricultural industry led to history’s greatest explosion in food production. The agricultural reforms and resulting production increases fostered by the “Green Revolution” are responsible for avoiding widespread famine in developing countries and for feeding billions more people since. The Green Revolution also helped kickstart a substantial increase to the world’s population — it took only 40 years for the population to double from 2.5 billion to five billion, between 1950 and 1990.

Norman Borlaug, an American scientist, is often called “the father of the Green Revolution”. In 1943 he began conducting research in Mexico regarding developing new disease-resistant, high-yielding varieties of wheat.

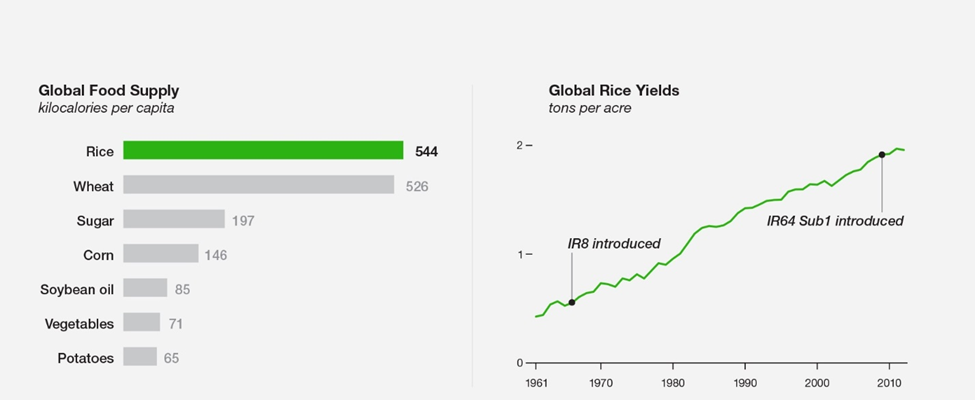

Through selective breeding, Borlaug created a dwarf variety of wheat that resulted in more grain per acre. Similar research at the International Rice Institute dramatically improved the productivity of rice, a cereal grain that feeds half the world.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, rice and wheat yields in Asia doubled, and though the continent’s population increased by 60%, grain prices fell, the average Asian consumed nearly a third more calories, and the poverty rate was cut in half. When Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, the citation read, “More than any other person of this age, he helped provide bread for a hungry world,” states National Geographic.

The term Green Revolution refers to a series of research, development and technology transfers that happened between the 1940s and the late 1970s. The initiatives involved:

- Development of high-yielding varieties of cereal grains

- Expansion of irrigation infrastructure

- Modernization of management techniques

- Mechanization

- Distribution of hybridized seeds, synthetic fertilizers, and pesticides to farmers

Tractors with gasoline-powered engines (versus steam) became the norm in the 1920s after Henry Ford developed his Fordson in 1917 — the first mass-produced tractor. This new technology was available only to relatively affluent farmers and it was not until the 1940s that tractor use became widespread.

Electric motors and irrigation pumps made farming and ranching more efficient. Major innovations in animal husbandry — modern milking parlors, grain elevators, and confined animal feeding operations — were all made possible by electricity.

Advances in fertilizers, herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, antibiotics and growth hormones led to better weed, insect and disease control.

There were also advances in plant and animal breeding — crop hybridization, artificial insemination of livestock, and genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Further down the food chain came innovations in food processing and distribution.

All these new technologies increased global agriculture production with the full effects starting to be felt in the 1960s.

The “revolution” in Green Revolution is well deserved.

The use of hybrid seeds, irrigation, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, farm machinery, and high-tech growing and processing systems combined to greatly increase agricultural yields. The Green Revolution is responsible for feeding billions — and likely enabling the birth of millions more.

Cereal production more than doubled in developing nations — yields of rice, maize, and wheat increased steadily. Between 1950 and 1984 world grain production increased by over 250% and the world added over 2 billion more people for dinner.

However, the Green Revolution was not as green as many think — there was collateral damage:

- Agricultural output did increase as a result of the Green Revolution, but the energy input to produce a crop increased faster — the ratio of crop production to energy input has decreased. This is because high yielding varieties of seeds only outperform traditional varieties when adequate irrigation, pesticides and fertilizers are used.

- Green Revolution agriculture produces monocultures of cereal grains. This type of agriculture relies on the extensive use of pesticides because monoculture systems with their lack of genetic variation are particularly sensitive to bug infestations.

- The transition from traditional to green agriculture meant farmers became dependent on industrial inputs, not made-on-the farm inputs. Farmers faced severely increased costs because they now had to purchase such items as farming machinery, fertilizer, pesticides, irrigation equipment and seeds.

- The increased level of mechanization on larger farms removed a large source of employment from the rural economy. New machinery, i.e., mass-produced tractors, self-propelled combines and mechanical cotton pickers all combined to sharply reduce labor requirements.

- Less people were affected by hunger and died from starvation but many more are affected by malnutrition such as iron or vitamin A deficiencies. Green Revolution grains do not have the same nutritional value as traditional varieties. The switch from heavily rotated multiple crops to mono-cropping or dual-cropping reduces soil fertility and the nutritional value of food.

- The Green Revolution reduced agricultural biodiversity by relying on just a few varieties of each crop. The food supply could be susceptible to pathogens that cannot be controlled by agrochemicals.

- Many valuable genetic traits, bred into traditional varieties over thousands of years, are now lost.

- Wild plant and animal biodiversity was hurt because the Green Revolution expanded agricultural into new areas where it was once unprofitable or too arid to farm.

- The 20/80 phenomenon — the rapid increase in farm size and the concentration of production among large producers means 20% of producers generate 80% of the agricultural output.

- As a result of modern irrigation practices, aquifers in places like India (once Borlaug’s greatest triumph) and the US Midwest have become depleted.

- Green Revolution techniques rely heavily on chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides, some developed from fossil fuels which makes today’s agriculture regime much more reliant on petroleum products.

- Farming methods that depend heavily on chemical fertilizers do not maintain the soil’s natural fertility and because pesticides generate resistant pests, farmers need ever more fertilizers and pesticides to achieve the same results.

- The increased amount of food production, and food’s low price, led to overpopulation worldwide.

Another Green Revolution?

The second half of the 20th century saw the biggest population increase in human history. Since 1950, the world’s population has gone from 2.5 billion people to 7.7 billion. According to the United Nations, the population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, with two-thirds of the growth over the next 30 years forecast to take place in Africa.

In a 2013 article, National Geographic poses the question: “Science prevented the last food crisis. Can it save us again?” The long-running natural sciences publication believes another green revolution is possible by continuing Borlaug’s work of breeding better crops but with modern genetic techniques; and that the negatives of commercial farming can be partially offset through organic food production.

To the first point, scientists can now identify and manipulate a large variety of plant genes for traits like disease resistance and drought tolerance, making farming more productive and crops more resilient.

The signature technology of this approach is genetically modified organisms (GMO). Since first tried in the 1990s, GMO plant species have been adopted by 28 countries and planted on 11% of the world’s arable land, including half the cropland in the United States.

Successful examples include a cross between a dwarf strain of rice and a taller variety from Indonesia that created India Rice 8, known for its role in preventing famine in Indonesia; drought-resistant varieties including one that can be planted in dry fields and subsist on rainfall like corn and wheat; and a flood-tolerant rice called Swarna-Sub1 that has been planted by farmers in Asia where every year floods destroy about 50 million acres of rice. A study of 128 villages in India that planted the rice variety increased their yields by more than 25%.

Opponents see farmers’ need to purchase GMO seeds from agro-giant Monsanto as a costly input to a broken agriculture system that relies too heavily on fertilizers and pesticides. Not only do the latter pollute the land, air and water, they also perpetuate a reliance on fossil fuels when they are applied.

“We need a farming system that is much more mindful of the landscape and ecological resources. We need to change the paradigm of the green revolution,” National Geographic quotes Hans Herren, a World Food Prize laureate and the director of Biovision, a Swiss nonprofit.

In Tanzania for example, farmers planted a diversity of crops — getting away from the Green Revolution’s emphasis on monoculture — to deter pests; the country now has one of the highest percentages of organic farmers in the world. As National Geographic notes, organic farming in Tanzania has liberated farmers from debt, in a country that, even with government subsidies, can cost more than $300 to buy enough fertilizer and pesticide to treat a single acre.

Of course, none of this matters to those uncertain of where their next meal is coming from. We now turn to the root causes of world hunger.

Causes of hunger

Poverty

That hunger is strongly correlated with poverty will surprise no-one. Poor people frequently face food insecurity and live in unsafe environments that have low access to drinking water, sanitation and hygiene. In developing countries, those lacking resources typically can’t afford the land or farming supplies they need to grow crops, or gain access to nutritious food.

Also, people living in poverty often get caught in a vicious cycle, where being hungry all the time means they suffer from low energy and reduced mental and physical functioning, which makes it difficult to work or learn. This leads to continued poverty and continued hunger.

Food waste

Canadians throw away $31 billion worth of food a year, from big box stores to common grocery shoppers. According to a 2019 report by Second Harvest, an agency that works to reduce food waste, an unbelievable 58% of all food produced in Canada gets green-binned or thrown in a dumpster, of which a third could be rescued and sent to communities in need.

Food waste is a big problem globally too. Medium.com referenced a journal article in 2018 that said 30 to 40% of food worldwide never makes it into a meal:

In less developed countries, this waste is due to lack of infrastructure and knowledge to keep food fresh. For example, India loses 30–40% of its produce because retail and wholesalers lack cold storage.

In more developed countries, the lower relative cost of food reduces the incentive not to waste. And as portion size grows, more and more food gets thrown out.

Think of how many restaurants in the US serve ridiculously super-sized portions (dinner-plate-sized pancakes anyone?) that are either left half-eaten or are contributing to the obesity and diabetes epidemics state-side.

Imagine how many people could be rescued from hunger if even one half of the one third of global food that is currently lost or wasted, went to those dealing with food insecurity?

Climate change

Society demands increased crop yields from agriculture in order to feed growing populations especially in the developing world.

Unfortunately, high-yield growth from Green Revolution advances is tapering off and in some cases declining. This is due to an increase in the price of fertilizers, other chemicals and fossil fuels, but also because the overuse of chemicals has exhausted the soil and irrigation has depleted aquifers.

Given this reality, “Climate change is acting as a brake. We need yields to grow to meet growing demand, but already climate change is slowing those yields,” Lifegate quotes Michael Oppenheimer, a professor at Princeton and co-author of the fifth report by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change).

Therein lies the quandary. We need higher crop yields, less waste and better distribution to feed more people, but climate change is making all of that harder to attain. In fact rising temperatures combined with more intensive agriculture to produce higher yields actually creates a feedback loop, that pushes CO2 levels even higher.

Desertification is human-caused degradation of land, including unsustainable farming, overgrazing, clear-cutting, misuse of water and industrial activities. Climate change accelerates desertification because warmer temperatures dry out once-fertile land, which then makes the area even hotter. Removing plants from the ground also increases greenhouse gas emissions, since they can no longer serve as carbon sinks. As we strip away the amount of available land for food production, we are literally depriving ourselves of the means to survive.

Here’s how it works: Ranching and farming, through extensive energy inputs like diesel fuel, lights, heating, etc., generate high amounts of carbon dioxide. Farming also releases methane from cows and cow manure, and nitrous oxide from fertilizers. Both are heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

As farmlands expand to meet demand for more food, forests are destroyed to make room for crops. Trees are carbon sinks that trap CO2 and prevent warming. Their removal dampens the forests’ mitigating effects on emissions from farming, therefore temperatures continue to rise.

A good example is soybeans. 95% of the soy that is made from soybeans is used as animal feed. To feed 700 million pigs in China — one for every two citizens — requires the importation of 800 million tonnes of soy. A lot of soybeans come from the Amazon region of Brazil, where rainforests, considered one of the most effective carbon sinks on the planet, must be logged to make room for more soybean farms.

Lifegate concludes: If greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase, as they are doing today, it will exacerbate those challenges and eventually make it all but impossible to control global warming without creating serious food shortages.

A report from the World Resources Institute concludes that feeding the world’s 9.8 billion in 2050 will require clearing most of the world’s remaining forests. The removal of the world’s carbon sinks would of course result in further warming, increasing the risk of crop failure and mass starvation.

In fact the UN’s often-quoted Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says we need to do precisely the opposite: shrink the amount of emissions-creating farmland and significantly increase the number of trees or other types of vegetation that can act as carbon sinks.

Unfortunately though, we appear no closer to achieving either objective. The planet continues to get hotter and climate change is reducing not only the quantity of food crops but the quality.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment found that climate change is already shrinking food supplies, particularly rice and wheat.

Disturbingly, the study quoted by The Conversation found that rising temperatures have reduced consumable food calories by 1% a year for the top 10 crops — maize (corn), rice, wheat, soybeans, oil palm, sugarcane, barley, rapeseed (canola), cassava and sorghum:

This may sound small, but it represents some 35 trillion calories each year. That’s enough to provide more than 50 million people with a daily diet of over 1,800 calories — the level that the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization identifies as essential to avoid food deprivation or undernourishment.

The number of climate-related disasters – drought, famine, floods, severe heat – has doubled since the early 1990s. One need only look back on the extreme weather events of 2021 to see how crops and livestock were negatively impacted, resulting in higher food prices. Drought in particular is responsible for 80% of damage and loss in agriculture.

According to World Vision, Our oceans, freshwater sources, forests, soil and biodiversity are rapidly degrading. Climate change continues to put pressure on these valuable resources, while ramping up the risks we face with natural disasters.

Conflict

The 1983-85 famine in Ethiopia prompted an out-pouring of support from pop musicians that resulted in the Live Aid benefit concert featuring some of the biggest acts of the day.

Although the famine was mostly attributed to a recurring drought and failed harvests, Human Rights Watch alleges it was in large part created by government policies, specifically a set of counter-insurgency strategies against Tigray People’s Liberation Front soldiers and for “social transformation” in non-insurgent areas. Read more on Wikipedia

Conflict remains a powerful antecedent of hunger, responsible for some 99 million people in 23 countries. The 2018 Global Report on Food Crises revealed that conflict and instability were the primary culprits behind food insecurity in 18 countries, accounting for 60% of the global total.

World Vision notes that,

As regions become increasingly volatile and besieged by violence, vital services and supplies become even more inaccessible to the most vulnerable. In fact, the UN estimates that 80 per cent of its humanitarian funding needs are directly attributed to conflict. It’s clear that future efforts to fight global hunger must go hand-in-hand with those to sustain world peace.

Hunger hot spots

There are currently a number of hunger “hot spots” whose crises are directly or indirectly attributable to conflict scenarios.

According to worldhunger.org, 14 million people in Afghanistan, whose government was recently overthrown by the Taliban, are facing acute food security, with an estimated 3.2 million children under five expected to suffer from malnutrition by year-end.

Thirty-six years after Live Aid, Ethiopia continues to suffer from the combined effects of civil war, loss of harvests and collapsed markets. This past May, it was reported that 5.5 million people faced acute food insecurity, including over 350,000 who were facing “catastrophe”. The food crisis has also created a humanitarian crisis, with over 100,000 fleeing their homes, of which some are crossing the border into eastern Sudan.

In Yemen, the food security situation has reached crisis levels with over 2.25 million children this year who are malnourished, due to the ongoing civil war, along with poor access to health services and poor sanitation.

Tellingly, all of the other hunger hot zones identified by worldhunger.org are in Africa. They include Somalia, Central African Republic, DRC, Kenya, Angola, Madagascar and Chad.

Conclusion

Adding 2 billion to the global population by 2050 will challenge agricultural networks and fisheries to produce enough food. However as our research has shown, narrowly focusing on increasing production as the Green Revolution did cannot alleviate hunger because it failed to alter three simple facts. First, an increase in food production does not necessarily result in less hunger — if the poor don’t have the money to buy food, increased production is not going to help them.

Poor people frequently face food insecurity. In developing countries, those lacking resources typically can’t afford the land or farming supplies they need to grow crops, or gain access to nutritious food.

Second, a narrow focus on production ultimately defeats itself as it destroys the base on which agriculture depends — topsoil and water.

We need higher crop yields to feed more people, but climate change is making that harder to attain. Climate change accelerates desertification because warmer temperatures dry out once-fertile land, which then makes the area even hotter. Removing plants from the ground also increases greenhouse gas emissions, since they can no longer serve as carbon sinks. As we strip away the amount of available land for food production, we are literally depriving ourselves of the means to survive.

And third, to end hunger once and for all, we must make food production sustainable and develop secure distribution networks of needed foodstuffs.

One way to grow food more sustainably is to plant genes for traits like disease resistance and drought tolerance, making farming more productive and crops more resilient. Though controversial, GMO crops are said to have prevented crop failures and may in some cases need less pesticides. Genetically-modified rice was credited for preventing a famine in Indonesia, with drought and flood-resistant varieties having been planted throughout Asia.

A return to more traditional farming methods such as planting a diversity of crops rather than relying on monoculture, and organic farming with its lack of pesticides, can make farming more affordable and is also better for the environment.

Developing secure food distribution networks is a harder ask. Conflict is a major driver of world hunger and governments or resistance movements often control the flow of food as a means of exacting concessions from the other party.

In the end the best way to prevent people from going hungry probably involves solutions that help them to help themselves. Governments obviously have a role to play in bailing farmers out from crop failures, and protecting them from lower-priced imports through tariffs and quotas.

Micro-financing programs, whereby non-traditional financial services are offered to the world’s poorest and most vulnerable, can also help a lot. According to World Vision, in 2018 alone, the microfinance industry helped nearly 140 million clients through savings, loans, insurance and transfers.

It’s easy to see world hunger and food insecurity as developing world problems, however as the pandemic has shown, sudden job losses can easily turn millions of people into food bank recipients.

Here in the West we can do our part to increase food security and eliminate hunger at the local level by donating to local food banks or soup kitchens, and simply by not wasting food, nor polluting the environment that depends on clean water and topsoil for growing productive crops.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.