The US needs Cypress’s lithium

2018.11.03

On June 11 Cypress Development Corp (TSXV:CYP) published its resource estimate for its Clayton Valley Lithium Project in Nevada on SEDAR, detailing the technical report it first published on May 1. Putting the NI 43-101-compliant report on SEDAR gave CYP added exposure to what might become one of the most exciting stories in junior mining this year.

The Vancouver-based company has so far flown under the radar of investors, trading at a ridiculous 0.32 cents a share as of close of trading Friday. Ridiculous in our opinion because the stock price is nowhere near reflective of what Cypress has in the ground, providing junior mining investors with a spectacular entry point. (Read “Cypress has world class Clayton Valley Nevada lithium resource” for our calculation on what CYP should be worth, based on the current market value of lithium in the ground, multiplied by CYP’s resource estimate and divided by its outstanding shares).

Before we run through the numbers, let’s set the stage with a little background on electric vehicles (EVs) and the lithium market, which is growing daily as countries make the shift from internal combustion engine (ICE)-based vehicles to EVs and more auto-makers and battery manufacturers enter the space.

The EV revolution

While modern electric vehicles have existed as prototypes and with very limited commercial production since the 1990s (General Motors’ EV1 – for a great history watch Who Killed the Electric Car?), the real momentum in the switch from cars equipped with gas and diesel-powered internal combustion engines to vehicles powered with lithium-ion batteries started in 2009 by then-President Obama. Obama announced his Administration was putting aside $2.4 billion in order for American manufacturers to produce hybrid electric vehicles and battery components.

Of course Tesla was a few years ahead of Obama, forming in 2003 and producing its first model, the all-electric Model S sedan, in 2008.

Electric vehicles have far fewer moving parts than gasoline-powered cars – they don’t have mufflers, gas tanks, catalytic converters or ignition systems. There’s also never an oil change or tune-up to worry about. But the clean and green doesn’t end there. Electric drives are more efficient then the drives on ICE-powered cars. They are able to convert more of the available energy to propel the car therefore using less energy to go the same distance. And applying the brakes converts what was wasted energy in the form of heat, to useful energy in the form of electricity to help recharge the car’s batteries.

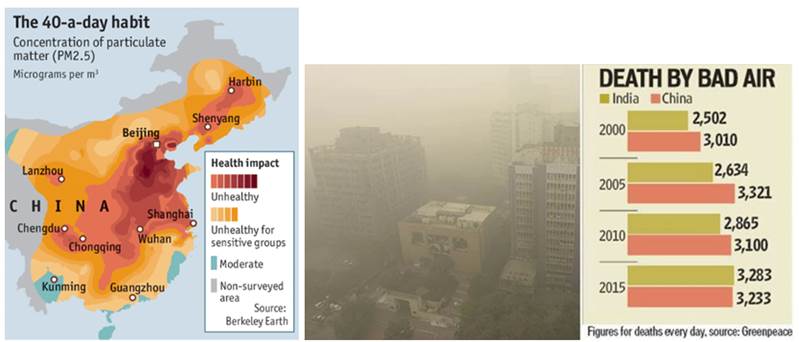

Electric vehicles are totally emissions free. China, the world’s second-biggest economy, in a move to cap its carbon emissions by 2030 and curb worsening air pollution, said it will set a deadline for automakers to end sales of fossil-fuel powered vehicles and push into the market led by Chinese EV juggernauts BYD and BAIC Motor Corp. India, France, Britain and Norway are doing the same.

But the key to EV market penetration has always been the batteries. How can they be made cheaply enough to compete with gas-powered vehicles, and with a reasonable range that doesn’t have the driver frantically searching for a charging station in the middle of nowhere? (As a personal aside, during a recent short drive from Kelowna to Vancouver an aheadoftheherd.com technician saw two EV charging stations at highway rest stops. The infrastructure is coming, folks)

Part and parcel to this question is lithium. Lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide are key components of the lithium-ion battery cathode, making it an extremely sought-after battery ingredient.

US lithium dependence

The Clayton Valley in Nevada started producing lithium in 1966 and the Silver Peak lithium brine operation owned by Albemarle is currently the only producing lithium mine in the US. In 2008 the National Research Council saw lithium as potentially becoming a critical mineral due to the expected growth of hybrid vehicle batteries. Two years later the US Department of Energy’s Critical Materials Strategy included lithium as one of 16 key elements. The country currently imports most of the lithium that it consumes – with import reliance today pegged at greater than 70%. Lithium is among 23 critical metals President Trump recently deemed critical to national security, and signed a bill that would encourage the exploration and development of new US sources of these metals.

It’s unfortunate for the United States that its dependence on lithium coincides with the ramping-up of demand for the white metal. But it’s also an extraordinary opportunity for Cypress.

Demand outstripping supply

Approximately 215 kt LCE was produced in 2016. Chile was the world’s

largest producer in 2016 with 37%, followed by Australia with 34%.

By 2025, if a very reasonable 30% of mining projects come to term, 700 kt LCE

will be produced. Australia will supply 45% of world production at this time; Chile

and Argentina will each supply 15%, China 10%, and the rest of the world 15%.

According to Roskill’s 15th edition market outlook report demand from companies that produce batteries to power electric cars, laptops, cell phones etc is expected to increase 650% by 2027, with overall lithium demand forecast to rise more than threefold over that period. Electric vehicle lithium-ion battery pack manufacturers share of the overall market for lithium-ion batteries will grow from 46% in 2017 to 83% by 2027.

Use of lithium hydroxide will increase from 25% of lithium compounds used in rechargeable batteries in 2021 to 55% by 2027.

The Chinese vehicle market is forecast to grow to 29.1m units this year, on its way to 38.2m in 2025 (equal to 52% of global volume growth over that period).By 2030, 40% of vehicle sales in the region will be EVs. The European car market is likely to expand by 2.5m units by 2030 to reach 23.1m units annually with a roughly 30% penetration of EVs by that time. The US will lag and only 16-21% or 2.6m–3.5m of sales in 2030 is likely to be electric.

“By 2030, Tianqi Lithium, SQM, Albemarle, and FMC, the companies that dominate the business, will have to supply enough lithium to feed the equivalent of 35 plants the size of the Tesla Gigafactory now being built in Nevada, according to BNEF. The total investment in new mines, including some for other elements used in lithium ion batteries, will likely range from $350 billion to $750 billion, according to analysts at researcher Sanford C. Bernstein & Co.” We’re Going to Need More Lithium, bloomburg.com

Of course the other elephant in the energy storage sector is the not oft talked

about growing grid level and behind the meter energy storage business.

“The energy storage market grew 46 percent between 2016 and 2017, with 28.6 megawatts deployed in Q3 2016 and 41.8 megawatts deployed in Q3 2017.51 Additionally, the market is projected to grow nine times between 2017 and 2022.5. Recent policies and developments have further supported the growth of the energy storage sector. For example, New York recently set a statewide energy storage target of 1,500 megawatts by 2025.53 Similar to those set in California, Massachusetts and Oregon, the targets help reduce regulatory barriers in order to further develop market growth.54 These investments are helping grow the energy storage sector rapidly, translating directly into new jobs. In 2016, employment in energy storage increased 235 percent from the previous year to reach 90,800 jobs, with battery storage accounting for over half of these jobs.” Climatecorps.org

According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) falling battery costs will have a huge impact on the electricity mix over the coming decades, BNEF predicts lithium-ion battery prices, already down by nearly 80% per megawatt-hour since 2010, will continue to tumble as electric vehicle manufacturing builds up through the 2020s.

“We see $548 billion being invested in battery capacity by 2050 – two-thirds of that at the grid level and one-third installed behind-the-meter by households and businesses. The arrival of cheap battery storage will mean that it becomes increasingly possible to finesse the delivery of electricity from wind and solar so that these technologies can help meet demand even when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining. The result will be renewables eating up more and more of the existing market for coal, gas and nuclear.” Seb Henbest, head of Europe, the Middle East and Africa for BNEF and lead author of NEO 2018.

Among the other highlights of BNEF 2018 report are predicted high penetration rates for renewables in many markets:

· 87% of total electricity supply in Europe by 2050

· 55% for the U.S.

· 62% for China

· 75% for India

Monster deposit

It is in this context that a new US lithium mine is being proposed next to Albemarle’s Clayton Valley Nevada, Silver Peak Mine. The timing is excellent. Silver Peak failed to increase production between 2012 and 2016 and its lithium grades are rumored to be dropping.

Cypress Development Corp has discovered a different type of deposit than the usual brine or hard rock lithium deposits, which must either be mined using drill and blast methods, or pumped into shallow ponds and allowed to evaporate, after which the concentrated lithium carbonate is extracted.

On May 1 the company published a huge maiden resource estimate, and is currently working on an economically feasible, metallurgical process for what Cypress believes is a large, bulk-tonnage deposit of leachable, non-hectorite clay.

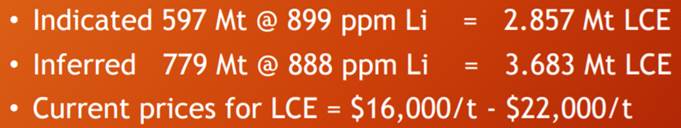

Of the 1.3 billion tonnes of lithium estimated in Cypress’ Clayton deposit, are 6.54 million tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) – 2.857 million tonnes indicated and 3.683MT inferred.

The estimate is based on drill results from 23 holes completed by Cypress in 2017 and 2018. The deposit remains open at depth, with 21 of 23 holes ending in lithium mineralization, meaning the drills have plenty of room to run in expanding and growing the resource.

The grades are also exceptional – 889 parts per million for the indicated mineral resource of 597 million tonnes and almost exactly the same, 888 ppm for the 779 million tonnes of inferred.

Of course, the size of a lithium deposit is of limited value if the metallurgy doesn’t work. In a recent article we discussed the difficulties of processing lithium, but in Cypress’ case the metallurgy looks relatively simple. The company has shown that lithium can be extracted from the clay using a flow sheet whereby recoveries of +80% can be achieved in short leach times (4 to 8 hours) using conventional dilute sulfuric acid and leaching. The amount of sulfuric acid and reagents needed is relatively low, and being able to leach the lithium with acid avoids costly calcine and regrind of material during processing, which would be the case if the deposit was hectorite clay.

A lithium “porphyry”

In an interview last week with Ahead of the Herd, Cypress’ CEO Bill Willoughby compared what Cypress has to an oxide copper porphyry deposit. While lower-grade than copper sulfide ores, copper oxide ores are usually cheaper to process, with the copper mineral leached using sulfuric acid, before being put through an electro-winning process. In the same way, Cypress’ lithium-rich clays at its Clayton Valley Project aren’t as high-grade as some hard rock lithium mines, but the mining and processing is simpler and less expensive.

“It’s the exact opposite of mines that are going into production where there are very high costs, high grade. We’re extremely low-cost, lower-grade,” says Willoughby – a mining engineer with a doctorate in mining and metallurgy, and an industry veteran with close to 40 years of experience.

Mining Cypress’ Clayton Valley deposit would be much simpler than hard-rock mining – the method used to extract lithium at the Greenbushes mine in Australia – the world’s largest hard-rock lithium mine – and Nemaska Lithium’s Whabouchi spodumene mine in Quebec. That’s because the deposit starts at an outcrop at surface and drops to around 350 feet underground.

“When you talk about a hard rock operation, you have drilling and blasting and overburden removal involved. It’s hard material, you’ve got to crush and grind to the appropriate size faction. Then you do gravity and flotation to make a spodumene concentrate and then it’s followed by pyrometallurgy and leaching.” Willoughby said.

“If you look at our flow sheet, we’re virtually just scooping the material out, putting it in the mill and we’re jumping straight into the hydro-met section, so you can see there’s a whole series of events that we’re bypassing.”

Easy metallurgy

There are two primary means of extracting lithium: from brines in evaporated salt lakes known as salars, and hard rock mining, where the lithium is mined from granite pegamite orebodies containing spodumene, apatite, lepidolite, tourmaline and amblygonite. The lithium at Cypress’ Clayton Valley deposit is a clay-like material that is soft when wet and chunky and hard when dry.

The clay itself is volcanic-derived ash that fell into a lake bed and metamorphozed into clay. One theory about the brine that Albemarle has been pumping over the years is that it’s derived from volcanic ash, which is the source of the lithium brine. Cypress believes that lithium-bearing brine aquifers could be located below the clay. The company has identified rare “mudstones” found at the eastern flank of the Clayton Valley; nothing similar has been found at other properties in the valley.

The lithium-rich mudstones likely were allowed to accumulate in a protected, lagoon-type environment, compared to the rest of the valley where boulders and debris were washed away throughout millions of years of rainy seasons.

The mudstone resources are broken down into five units which are distinguished by stratigraphic position and color (see table below). The middle three units are higher grade and estimated to average greater than 950 ppm Li, whereas the uppermost and lowermost units average less than 700 ppm Li.

The lithium would be processed from a pregnant leach solution, similar, as mentioned, to processing copper oxide ore. Iron, silica, calcium and magnesium are precipitated out, leaving a solution containing lithium, potassium and sodium. The latter two minerals can be sold as by-products.

The process is different from a lithium brine operation one might find in Chile or Argentina, because it involves a conventional mill, versus evaporation ponds found for example in the Salar de Atacama, Chile. That also saves time. Lithium brines can take up to take up to two years to evaporate and concentrate the lithium.

Willoughby noted the metallurgical flow sheet CYP has tested so far has three advantages: “We have a fast extraction time, so we’re under eight hours on an extraction. We’re low acid consumption, we’re probably going be under 100 kilos per ton of sulfuric acid per ton of clay processed. And because of the nature of our processing and a couple things we figured out in the circuit, we’re going to be low on our neutralization needs and that’s mainly in adding lime to the circuit to knock out the other elements.”

Cypress’ consultants ballpark the cost of production between $2,500 and $4,000 a tonne of lithium carbonate equivalent. More definite figures will be contained in the upcoming preliminary economic assessment (PEA). Set against an average 2017 price of $13,900/t for lithium carbonate, the economics are already looking great. But Willoughby knows the company needs to continue proving out the metallurgy, and that’s where the company is focused.

“I think right now we’re in the state of, ‘Show us that you can actually produce this material,’ he told Ahead of the Herd. Laboratory test work indicates that Cypress has the ability to produce a high purity lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide product on site.

50 years worth of LCE, to start

Cypress has identified about 200 million tonnes of ore, estimated to contain a million tonnes of LCE, it would use for its initial open pit mine. The company is targeting 20,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate (LCE) production a day (1,000,000/20,000 = 50 years of mining), which is bang on 10% of the current global 200,000 tonnes per year LCE production.

Ten percent of world production is considered to be enough to affect the lithium price, so if Cypress goes mining and starts producing at the numbers it hopes to, the mine will be a price setter and will influence the entire lithium market.

The term “starter pit” is a misnomer because even that small chunk of the immense resource contained on Cypress’ Clayton Valley property has the ability, at current global LCE demand, to supply the entire world lithium market for five years. (1,000,000 tonnes of LCE divided by 200,000 tonnes annual global production).

Start scaling up, add another mine, or two, to the property, and the numbers become even more impressive. The indicated resource of 2.8 million tonnes LCE would supply the entire global current market for 14 years. But with lithium demand continuing to grow, we should put the annual production at 300,000 tonnes, for projection purposes. That would still give Cypress 9.3 years worth of global LCE supply by mining the indicated. Add in the inferred, which Cypress plans to upgrade to indicated with more drilling, and that’s another 12 years of lithium supply.

America’s mine

There currently exists no mine to battery supply chain in North America – not in the United States nor Canada. At Albemarle’s Silver Peak Mine, the lithium, produced at around 3,500 LCE a year, is shipped to Kings Mountain in North Carolina, which produces lithium hydroxide needed for lithium-ion batteries. This material is then loaded on ships and sent to Asian battery manufacturers, which sell the batteries to auto-makers. The irony is that Tesla’s Gigafactory in Nevada is located just a short distance away from Cypress’ Glory and Dean deposits.

But Tesla has shown little interest in making deals with current (Albemarle) and future US lithium miners – despite Elon Musk’s entreaties to source its lithium from North America. While it’s true that Tesla signed an agreement with Pure Energy Minerals, also exploring in the Clayton Valley, to supply it lithium hydroxide, Tesla has been sniffing around the Chilean salars for a long-term source of lithium for its high-end electric vehicles. The company inked a deal in May with Kidman Resources, an Australian company, which is developing a lithium processing plant in Western Australia with SQM, the largest lithium producer in Chile. Tesla plans to buy lithium hydroxide from Kidman and manufacture batteries in China for its Nevada gigafactory.

North of the border, Canadian lithium miners aren’t looking in their own backyards either to build an EV battery supply chain. Nemaska Lithium will send its lithium hydroxide to Swedish battery maker Northvolt AV, which will take between 3,500 and 5,000 tonnes per year. Nemaska has also made deals with Asian companies, in April accepting an investment of $78 million from Japan-based Softbank, the world’s biggest technology investment fund ($100 billion) in return for a 9.9% stake. In May Nemaska agreed to supply spodumene concentrate to Hanwa Co., Ltd. of Japan and General Lithium Corp from China.

You can hardly blame the battery-cos from locking up lithium supply in offtake agreements with future lithium miners. As the prices of EV battery ingredients – copper, lithium, cobalt and graphite – continue to climb and the prices of finished products, the batteries, continue to fall margins are being squeezed, these companies need to hedge their bets, hence the off-take agreements securing long term prices/supply. But wouldn’t it be great if North American lithium mining companies kept their lithium on the continent instead of shipping it overseas?

If we want a lithium-ion battery industry and electric vehicles built in North America we need lithium security of supply. No longer can we rely on the good graces of other countries, namely Australia, China, Chile and Argentina, where 90% of the lithium is produced. We need to develop an energy metals industry in North America – from mine to battery.

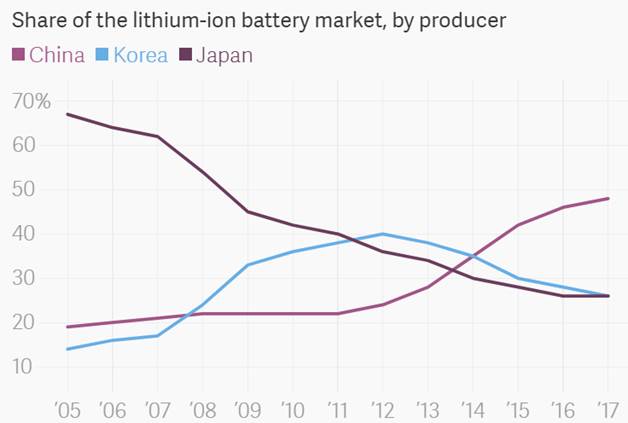

Asia and particularly China are looking to lock up lithium supply, and are years ahead of North America in terms of EV penetration and battery supply chains. Last year China sold about 700,000 electric cars, 200,000 more than 2016. Government subsidies to EVs have been reduced by 20%. The Asian superpower sees EVs as the key to unlocking the pollution dilemma that has plagued its car-choked cities. China represents over a quarter of the global EV market, and will own 40% by 2040 according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). The country has signed lithium offtake agreements with mines in Australia, Canada and Africa.

In May Tianqi Lithium – which owns 51% of Talison’s Greenbushes mine in Australia, the largest hard rock lithium mine in the world – succeeded in purchasing a 24% stake in SQM, paying $4.1 billion to buy it from Canada’s Nutrien – the world’s largest potash miner. The company was created through the merger of PotashCorp and Agrium.

But Chile doesn’t want to lose control of lithium, which it considers to be a strategic metal, and rightly so. Citing concerns that China is trying to create a lithium monopoly, Chile in March filed a complaint trying to block Tianqi from acquiring the stake.

But according to Corfo, Chile’s economic development agency responsible for overseeing SQM’s lithium leases in the Salar de Atacama, Tianqi and SQM combined will now control 70% of the global lithium market. Tianqi is aiming to nearly triple production capacity through 2020.

The race to lock up lithium in Chile is actually good news for Cypress, because having a mine in the United States frees up the company to cut deals with Tesla or other domestic auto manufacturers rather than trying to compete with the Chinese who are already sealing offtakes in South America and Australia. This is especially important now, considering that we are in the early stages of a trade war between the United States and China, with lithium in the crosshairs.

Earlier this month, the US threatened to impose $200 billion worth of additional tariffs on Chinese imports, adding to the $150 billion in tariffs already in play from both sides – not including steel and aluminum duties. China vowed to retaliate in kind. The US has already promised 25% tariffs on about $50 billion worth of Chinese products, including semiconductors and lithium batteries.

In the midst of this trade instability, imagine a North American mine that can supply lithium to American car companies, making electric vehicles, in the US, free of tariffs? And with no foreign offtake agreements in place – the only North American lithium mine that can say that. Willoughby told Ahead of the Herd that Cypress’ intention is to supply local. “In my mind, I see the battery plant up the road at Tesla, that would be a nice ‘Made in Nevada’ story.”

Conclusion

Three years ago Cypress began prospecting in the Clayton Valley, home to Albemarle’s Silver Peak Mine, which has been mining Nevada lithium brines for decades.

Cypress’ Clayton Valley Lithium Project is an elephant. The sheer size of the resource means that a lot of attention will be focused on the company, particularly beneficiation methods. With a million dollars in the kitty, Cypress is well-financed.

Cypress has a non-hectorite claystone, starting at surface deposit in Nevada, USA. No tariffs, no trade war worries, next to the only producing lithium mine in the US and in the home state of Tesla’s Gigafactory, which needs lithium. With its monstrous resource, high-grade lithium content, a superior location in regard to permitting and all the existing infrastructure in place, the uniqueness of the new deposit model, and with no competition in the Clayton Valley basin, Cypress is focused on perfecting its metallurgy and proceeding to the next stage, a PEA, slated for July, with a prefeasibility study planned for shortly thereafter.

Could Cypress be THE company with THE lithium mine in the US that provides lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide security of supply to a US based battery manufacturing sector freeing the US from foreign dominance of its EV revolution?

Could Cypress Development Corp (TSX.V:CYP) actually own the means to developing a US mine to battery manufacturing sector? The possibility is certainly very real, and exciting.

I see two possibilities here for investors. One is that Cypress will take this project all the way to production, and from what Willoughby has told us, that is the plan. On the other hand, juniors, especially those with mining engineers at the helm, often take that position with investors, but as we all know, no reasonable explorer will refuse a buyout. How often have you heard, “We’re going mining, we’ve got the project, the team is assembled, it’s just a matter of doing the studies and acquiring the permits……..What’s your offer?”

I’ve got Cypress Development Corp and upcoming catalysts, including what we here at aheadoftheherd.com anticipate to be a very attractive PEA coming shortly, on my radar screen.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Just read, or participate in if you wish, our free Investors forums.

Ahead of the Herd is now on Twitter.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified.

Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Richard owns shares of Cypress Development Corp. (TSX.V:CYP).

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.