The inevitability of rising food prices, global famine – Richard Mills

2023.06.16

Simultaneous and dramatic price increases for energy and food are part of a ballooning cost-of-living crisis in much of the developed world, as inflation continues to wrack economies and central banks try to control it through interest rate increases that are impeding growth, and threaten to plunge the global economy into recession.

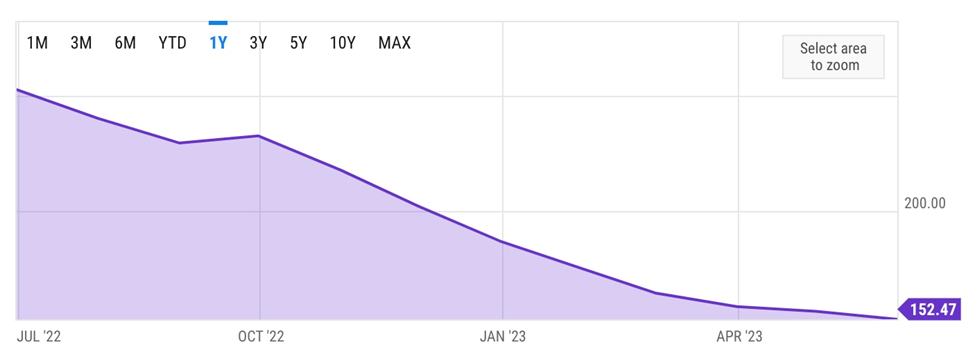

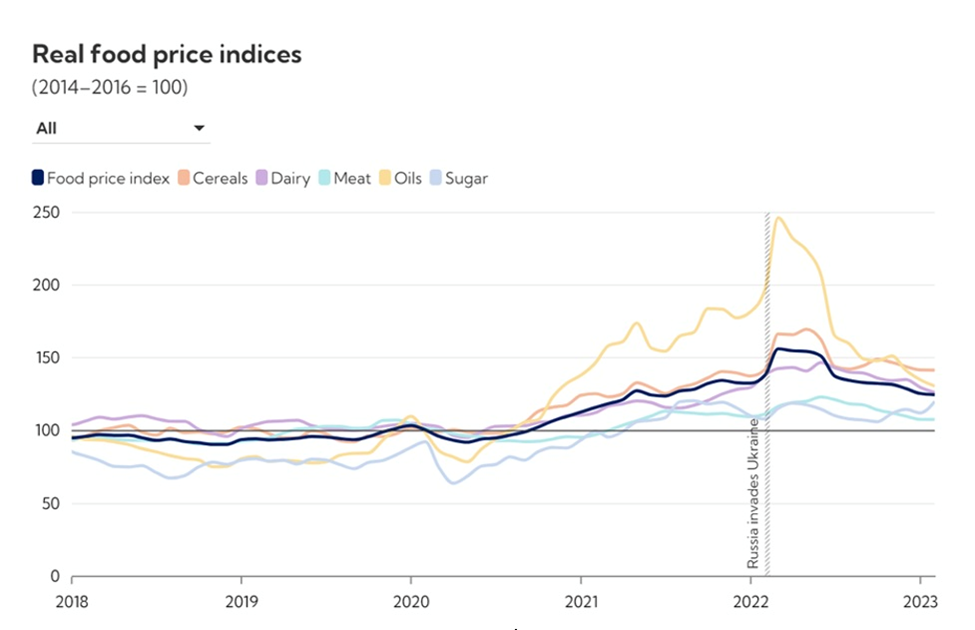

In April, the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) food price index rose for the first time in a year, reflecting higher prices for sugar, meat and rice. Although the UN gauge in May was 22% lower than the record set in March 2022, when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted grain exports, concerns over food inflation, and global hunger, persist.

According to the 2023 Global Report on Food Crises, last year saw a 33% spike in the number of people facing hunger, up from 193 million in 53 countries and territories in 2021. 2022 was also the fourth consecutive year that an increasing number of people experienced Phase 3 food insecurity, says the report, written by the Global Network Against Food Crises and the Food Security Information Network.

Unfortunately, the situation is unlikely to improve in 2023, due to several intertwining factors: rising input costs, inflationary pressures, supply chain disruptions, and extreme weather.

5 reasons food will get scarcer and more expensive

Addressing each of these briefly (click on the above link for more detail), we note that:

- The world’s food markets are so interconnected that inflationary pressure in one market can creep into another, and producers have no choice but to raise prices. Indeed, input costs faced by food producers — such as labor, packaging and energy — have all shot up over the past year.

- A new report by Fitch Ratings reveals that the food component of consumer inflation has continued to rise even as many of the primary inputs used in food production, such as fertilizer, have dropped significantly. The resilience of food prices partly reflects the fact that manufacturers and retailers face broader costs than just the price of primary inputs, the report said. These include rising wages in labor-intensive retail segments like grocery stores and restaurants. It can take as long as a year for the effects of declining input costs to impact retail prices.

- Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, producers have been heavily impacted by supply chain disruptions that caused the prices of grains like soybeans and vegetable oils to spike. Though the supply shocks have somewhat subsided, concerns over food insecurity remain elevated, as inflation-adjusted prices in 2023 are still above average.

A study recently published in ‘Nature’ found that extremely hot and dry events have consistently negative effects on the yields of all inspected crop types. In California, which has been hit by droughts for four consecutive years, rice farmers reportedly sowed the lowest number of seeds since the 1950s, equivalent to about half of a typical season. The US wheat harvest fell 25% last year as drought hit Midwestern states like Kansas. Snow, torrential rains and massive floods also tormented US farmers. The World Food Program has forecast that 345.2 million people will be food insecure in 2023 due to extreme weather events.

Droughts

Let’s take a closer look at droughts and heat, since they have a direct bearing on food production.

Around harvest time last year, the Wall Street Journal reported that staple crops like corn, rice and Mexican chilies, all of which are vulnerable to hot weather and a lack of water, were seeing yields a fraction of normal levels.

Waterways that typically feed agricultural systems were parched, including Italy’s River Po, which accounts for up to 40% of the country’s agricultural production; and China’s Yangtze River, a crucial life source for crops. France in 2022 experienced the most severe drought ever recorded and China had the driest summer in six decades.

The newspaper noted that nearly 30% of corn production is based in areas hit by drought and record-high temperatures.

“When you put that hot weather on top of the drought, that’s really the key thing here it’s the drought and heat wave that has just been so bad this summer, and it’s put a lot of stress on farmers,” Wall Street Journal reporter Patrick Thomas said in September, 2022.

Gustavo Naumann from the International Center on Environmental Monitoring pointed out the interconnection between local market conditions and globally, particularly for crops grown in so-called breadbaskets like South America, central US, Ukraine, India and China. When a drought hits one or more of these areas, there is less supply of staple crops in the global market, which pushes prices up.

Scientists, says the WSJ, forecast there will be an uptick in frequency and severity of droughts, as temperatures continue to rise and that means economies are going to have to brace themselves as droughts can threaten global food security.

In fact the evidence is already showing that 2023 is likely to be a repeat of 2022, meaning another summer of parched fields and searing heat for farmers and ranchers worldwide.

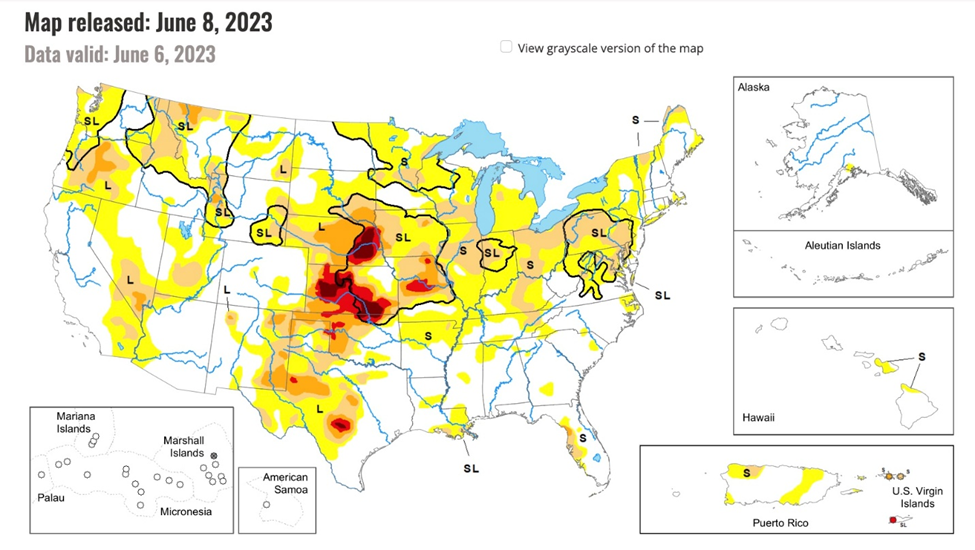

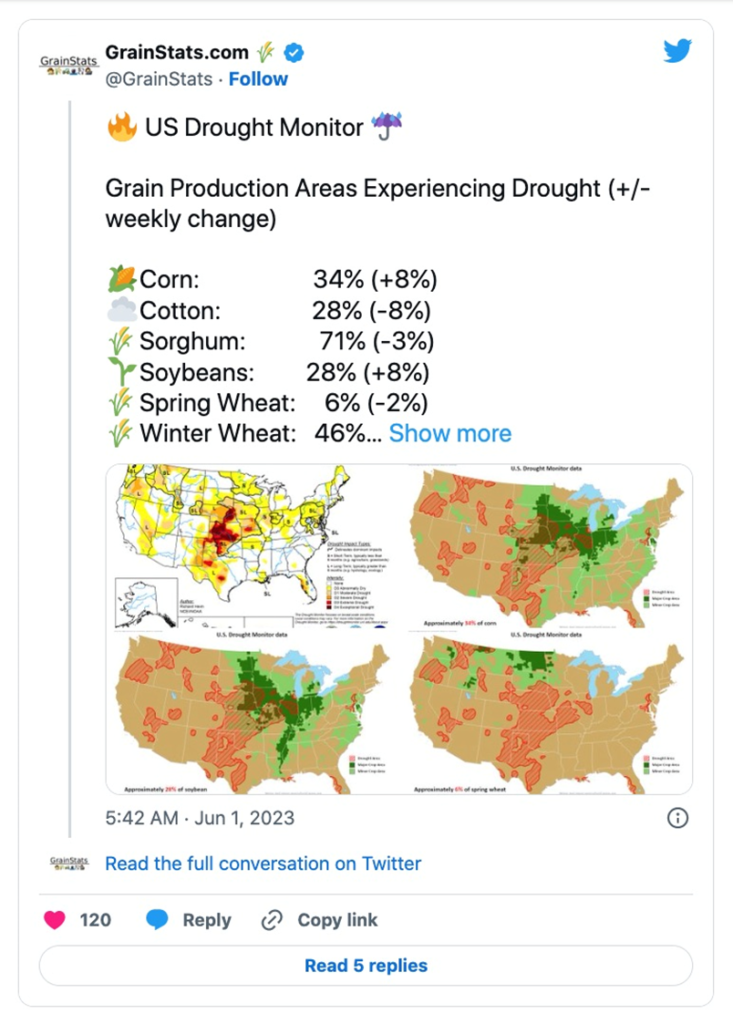

Take what’s happening in Kansas as a harbinger. The state normally produces far more wheat than any other state, but Kansas wheat farmers will reportedly reap their smallest harvest in more than 60 years, the result of a two-year drought that has withered the crop.

Things are so bad, flour mills will likely have to buy wheat grown in eastern Europe.

One solution might be to switch to corn, but corn farmers are also facing problems caused by drought. A recent Newsweek article titled ‘Corn Price Set to Soar After Midwest Hit by Worst Drought in 30 Years’ states that,

An unusually dry May in the Midwest has raised concerns over this year’s corn crop in the Corn Belt, the region stretching from the panhandle of Texas up to North Dakota and east to Ohio which dominates the country’s corn production.

But it isn’t only corn and wheat farmers who are suffering. The size of the US beef cow herd is reportedly the smallest since 1962; the orange harvest in Florida will be about 56% less than last year; and thanks to weird weather in Georgia, approximately 90% of the peach crop has been destroyed.

Just like last year, the ultra-dry conditions are being accompanied by unusually hot weather. The proof is again via Newsweek:

The USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service recently reported increasingly dry topsoil, poor pasture conditions in Missouri, and limited moisture for newly planted crops.

“We have very high temperatures all the way up through the northern plains of the Midwest, which impacts more than just corn and soybeans—it’s impacting other crops as well,” Curt Covington, senior director of partner relations at AgAmerica, America’s largest nonbank agricultural lender, told Newsweek.

According to US Drought Monitor, the corn belt states of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio and Wisconsin, are all experiencing “exceptional drought” to “moderate drought.” Dry conditions so early in the season could stress the young plants.

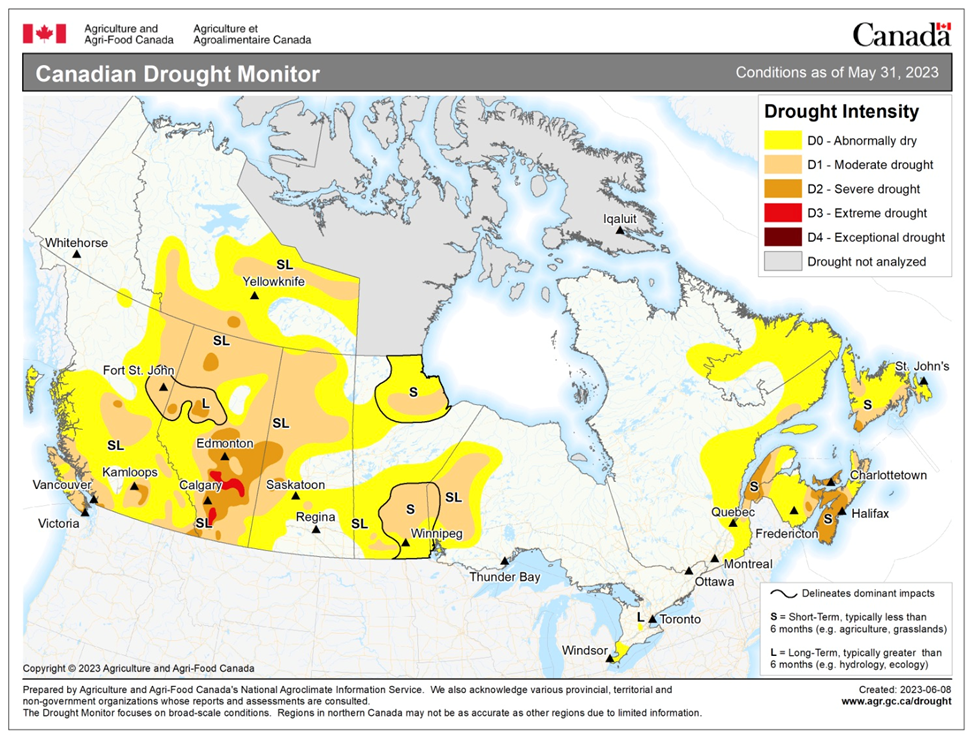

This year, droughts have come earlier to Canada as well, which is on track to experiencing its worst wildfire season in history. One week before the official start of summer, 4 million hectares have already burned. The fires aren’t restricted to Western Canada, as they are normally. Forest fires have erupted across the nation, including in BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia.

Rest of Canada, parts of US sharing in BC’s wildfire misery

Nearly half the country (47%) at the end of May was classified as abnormally or in moderate to extreme drought, including 70% of the agricultural landscape.

According to provincial forecasters, much of BC could see little to no rainfall this summer, a scenario that should worry the province’s farmers and ranchers who depend on water for their livelihoods. The most recent Snow Survey and Water Supply Bulletin, quoted by CBC News, warns of “long-term, significant drought” unless there is substantial and sustained rainfall over the coming months.

The province this year is on pace to be the earliest snow-free ever recorded, following abnormally hot weather in May.

Low water levels affect not only crops but livestock and fish. Cattle ranchers, for example, need water and grass to feed their herds.

“If we don’t get the rain to grow the grass, we have no choice but to reduce the amount of cattle we have,” Kevin Boon, general manager of the B.C. Cattlemen’s Association, told CBC News. “We are not going to starve our animals.

“Unfortunately when we see a widespread drought … often the only opportunity for that breeding stock is to send them to market and to be processed for food, and that is very challenging for our guys that have spent generations building herds.”

Predictably, the result of lower US food production will be continued higher food prices, which have been weighing on consumers for more than a year now. More expensive grocery items disproportionately affect those with lower incomes, since their food budget represents a greater chunk of their monthly income than those better off.

While US food inflation has been nearly cut in half from its August, 2022 peak, May’s 6.7% is still higher than normal. (A 10-year chart shows food inflation hovering between 0 and 4%)

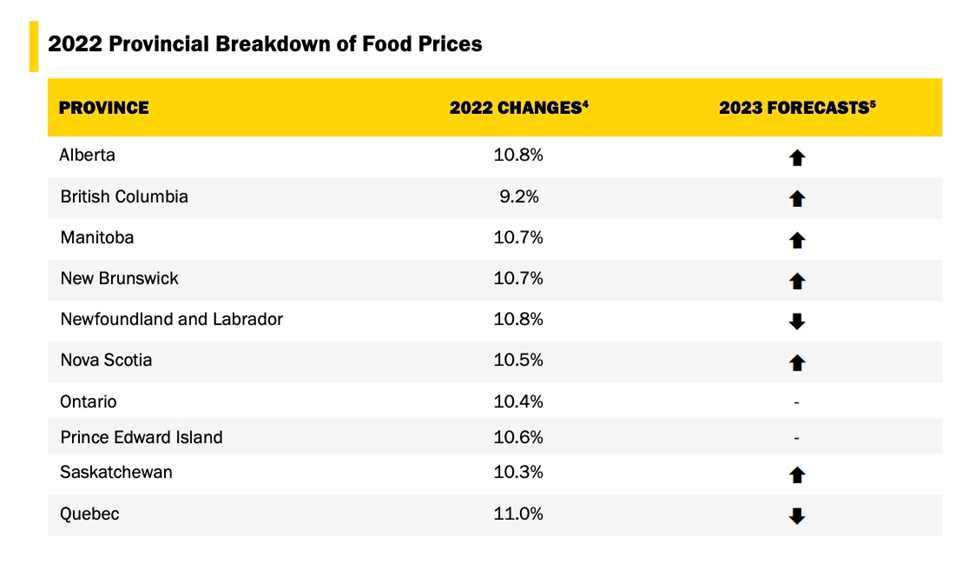

In Canada, food prices rose 10.3% in 2022, and this year they are expected to climb between 5 and 7%. According to ‘Canada’s Food Price Report 2023’, a family of four will have an annual food expenditure of $16,288, an increase of $1,065 over last year. And inflation is compounding, last years 10.3% adds to this years 5-7% for a 2 year rise of between 15.3 to 17.3%. That’s a hard hit to the folks who can afford it least.

A 2022 provincial breakdown shows Quebeckers saw the highest food inflation of 11%, with the rest of the 10 provinces experiencing double-digit price increases except for British Columbia, which had 9.2%. In 2023, an above-average food price increase is expected in 60% of the provinces, with only two, Newfoundland/Labrador and Quebec, expecting a below-average food price increase. No forecast was provided for Ontario and Prince Edward Island.

Like in the United States, higher Canadian food prices are attributed to rising input costs, inflationary pressures, supply chain disruptions and extreme weather.

Think back to 2021, when a hot, dry summer baked the Prairies. While 2022’s growing season was a significant improvement, a good amount of the region is still running a deficit of soil moisture.

“Because we’re starting out with abnormally low soil moisture reserves, it means the impact of any shortfall and moisture during the growing season is going to be just that much worse,” Edward Bork, an expert in rangeland ecology and management at the University of Alberta, told CBC News earlier this year. “There’s no soil moisture reserves to bail out or try to stabilize our production.”

That, combined with above-normal temperatures, could spell trouble for Canadian farmers and ranchers. According to a three-month weather forecast from Environment Canada, May, June and July are expected to be warmer than normal in much of Canada, with portions of northern Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba having a 70 to 90% chance of hot weather.

Gro Intelligence confirms that so far this year, rainfall over the Canadian prairies is at one of the lowest levels this century. Its Gro Drought Index still shows “abnormally dry” conditions in spring wheat growing regions.

A similar tune is sung across the world. India, the second-largest food producer, is experiencing another year of extreme weather, recording its hottest February in over a century; southern Europe’s farmers are still dealing with a crop crisis following months of drought; and the Horn of Africa is about to record a sixth consecutive failed rainy season.

Hundreds of millions going hungry

For most Western consumers, higher food prices are a source of angst, and they can mean economic hardship for the lowest income earners. In developing countries, high food prices carry a much more serious consequence: starvation.

The World Food Program says Conflict, economic shocks, climate extremes and soaring fertilizer prices are combining to create a food crisis of unprecedented proportions. As many as 828 million people are unsure of where their next meal is coming from.

More than 345 million face high levels of food insecurity in 2023, more than double the number in 2022. The biggest driver of hunger is conflict, with 70% of the world’s hungry living in areas affected by war.

Climate change weighs in at number two, with climate shocks destroying crops and livelihoods, and undermining people’s ability to feed themselves. WFP says high fertilizer prices could turn the current food affordability crisis into a food availability crisis, with production of maize, rice, soybean and wheat all falling in 2022.

Costs are also at an all-time high: WFP’s monthly operating costs are US$73.6 million above their 2019 average – a staggering 44 percent rise.

The IMF says With two of the world’s largest exporters of wheat and other crucial crops entering a second year of war, many vulnerable countries still face heightened food insecurity. Fragile and conflict-affected states, home to 1 billion people, are at particular risk.

World Food Program USA identified the 10 countries suffering most from hunger. The DRC leads with 26 million facing severe hunger; followed by Afghanistan @ 19.9 million; Yemen @ 17 million; Syria, The Sahel, South Sudan, Sudan, Somalia, northern Ethiopia and Haiti.

Conclusion

Ongoing conflicts such as the war in Ukraine, the DRC and Yemen, are displacing millions of people and limiting access to food.

Droughts and heat resulting from rising temperatures are causing disruptions to agriculture in some of the most fertile regions of the world. El Nino, the 9 months to a year climate pattern set to take over from La Nina, is only expected to make the situation worse.

El Nino causes the Pacific jet stream to move south and spread further east. During winter, this leads to wetter conditions than usual in the southern US and warmer, drier conditions in the north.

This summer is shaping up to be the worst-ever season for forest fires in Canada as hot and dry conditions persist.

Nearly half the country at the end of May was classified as abnormally or in moderate to extreme drought, including 70% of the country’s agricultural landscape.

Unless these areas receive rain, farmers and ranchers are in for another nightmarish season of falling yields and culled herds that could force many into bankruptcy.

South of the border, in the much larger US agriculture market, a two-year drought has withered the wheat crop in Kansas leading to what is expected to be the smallest harvest in 60 years. The astonishing dearth of local product means Kansas flour mills will likely have to buy wheat grown in Europe.

Corn-belt states are also facing misery, due to an unusually dry May. The Florida orange harvest looks to be over 50% less than last year, extreme weather has all but destroyed the Georgia peach crop, and the size of the US beef cow herd is the smallest it’s been since 1962.

The lower yields are expected to keep US food prices elevated, despite input costs like fertilizer and fuel decreasing in price.

Given that Canadians buy a lot of meat and produce from the United States, US food inflation will almost certainly affect how much Canadians will have to pay for their weekly shop.

Prices are expected to go up 5-7%, but I’m thinking that’s optimistic. If drought conditions persist and food-growing regions get a string of hot weather, I’d expect food to become even more expensive.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.