The Great Stagflation 2.0 and gold

2022.08.16

In 1979, then US Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker faced a serious challenge: how to quell inflation which had been wracking the economy for most of the decade. The prices of goods and services had averaged 3.2% annually since World War II, but after the 1973 oil shock, they more than doubled, to an annual 7.7%. Inflation reached 9.1% in 1975, the highest since 1947. Although prices declined the following year, by 1979 inflation had reached a startling 11.3% (led by the 1979 energy crisis) and in 1980 it soared to 13.5%.

Not only was inflation going through the roof, but economic growth had stalled and unemployment was high, rising from 5.1% in January 1974 to 9% in May 1975. In this low-growth, hyperinflationary environment we had “stagflation”.

Volcker is widely credited with curbing inflation, but in doing so, he is also criticized for causing the 1980-82 recession. The way he did it was the same as the current US Federal Reserve is fighting inflation: raising the Federal Funds Rate. From an average 11.2% in 1979, Volcker and his board of governors through a series of rate hikes increased the FFR to 20% in June 1981. This led to a rise in the prime rate to 21.5%, which was the tipping point for the recession to follow.

Forty years later, the Federal Reserve faces a familiar foe, in rising and persistent inflation. And like Paul Volcker’s Fed, interest rate hikes are being touted as the solution to bringing it back in line.

The “monetary tightening” policy hasn’t worked, so far. Inflation has actually accelerated since the Fed began raising rates in March, prompting officials to hike them by a half-percentage point that month, instead of the earlier 25 basis-point expectation, and 75 basis points in June rather than the 50 points the Fed thought would be sufficient. In July, at the Federal Open Market Committee’s regular meeting, the central bank approved another 0.75% increase, lifting its benchmark overnight borrowing rate to a target range of 2.25% to 2.5%.

It seems the Fed is hell-bent on bringing inflation down to its 2% target, despite indications its tightening has already damaged the US economy, and is pushing it rapidly into recession if it isn’t there already.

The Fed’s pickle

The organization is grappling with how best to reduce inflation, which by its measure is running at more than three times the Fed’s 2% target, without causing a recession or pushing unemployment higher by lifting interest rates too much.

The Fed has two options when it comes to interest rate increases designed to tackle the highest US inflation in 40 years. The first is it continues to hike rates, beyond what the economy can handle, causing a recession, defined as two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth. (technically we are already in a recession, with US second-quarter GDP falling by 0.9%, and Q1 GDP declining by 1.6%).

Bloomberg wrote in April, The consensus is that the Fed is so far behind that curve when it comes to increasing rates that it will have no choice but to tighten monetary policy so severely that it forces the economy to contract to get inflation under control.

In the second option, the Fed hits “pause” on interest rate hikes. Under this scenario, the central bank could even reverse course, like it did in 2018, and return to lowering interest rates and its monthly purchases of bonds and mortgage-backed securities, a policy known as “quantitative easing”, or QE. But it would take awhile to do so.

The result, imo, of either option is stagflation, a particularly nasty combination of high, persistent inflation, stagnant growth and soaring unemployment, as the economy implodes under central banks’ failed efforts to control inflation.

Recession signals flashing

While the Fed has been focused on positive economic data, such as relatively low jobless claims, one doesn’t have to look very hard to find indications of a US economic slowdown.

What about the fact that the country’s GDP shrank for the second straight quarter, and that since 1948, the economy has never seen consecutive quarterly growth declines without being in a recession? How about the yield curve inverting? Does anyone at the Fed care that the current 2-year US Treasury yield is higher than the 10-year and the 30-year, the “yield curve inversion” being an extremely reliable recession indicator? The FRED chart below shows the 2-year/ 10-year yield curve in a state of inversion (the blue line below zero) since July 8.

The Misery Index measures the amount of economic distress felt by average people, due to the risk of, or actual joblessness, combined with an increasing cost of living (inflation). The index is calculated by adding the unemployment rate to the inflation rate.

As the chart below shows, the Misery Index has risen steeply since July, 2021. In June, 2022, the index hit 12.5, the highest since 2011 when the US economy was experiencing very weak job and economic growth following the financial crisis. June’s figure also rose above the index from the 2007-09 Great Recession, and was just about equal to where it was in the run-up to the 1990-91 recession. (recessions are shown as light blue shaded vertical bars)

The second chart below graphs the Michigan Consumer Sentiment trend alongside the Misery Index. It shows consumer sentiment has plummeted almost lock-step with the increasing Misery Index, and has done so for decades.

This makes perfect sense. Consumer sentiment should naturally reflect the amount of economic distress being measured by the Misery Index.

The Producers’ Manufacturing Index is showing weakness, as high inflation impacts customers’ ability to pay, and higher interest rates make borrowing more expensive. As the chart below shows, the S&P Global Flash US PMI Composite Output Index fell for the first time in over two years (26 months), led by services. Manufacturers and service providers both reported subdued demand conditions.

“The preliminary PMI data for July point to a worrying deterioration in the economy. Excluding pandemic lockdown months, output is falling at a rate not seen since 2009 amid the global financial crisis, with the survey data indicative of GDP falling at an annualized rate of approximately 1%. Manufacturing has stalled and the service sector’s rebound from the pandemic has gone into reverse, as the tailwind of pent-up demand has been overcome by the rising cost of living, higher interest rates and growing gloom about the economic outlook,” said Chris Williamson, chief business economist at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

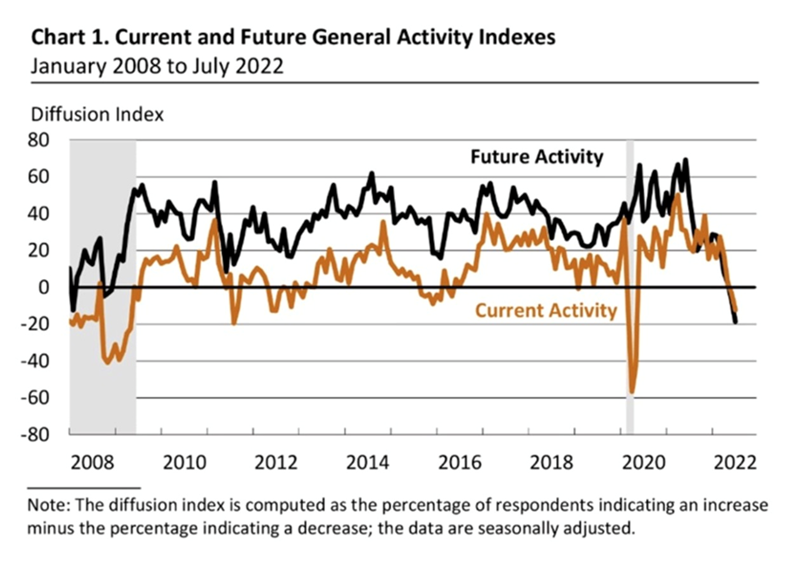

The S&P PMI confirmed figures that came out from the Philadelphia Fed Manufacturing Index, showing the index plunged for the fourth straight month. Even more worrying was the gauge of future economic activity, with -18.6 indicating the worst reading since 1979.

The New York Fed’s Empire State Manufacturing Survey adds to the darkening economic picture. The first regional manufacturing survey of August unexpectedly cratered from 11.1 to -31.3, demolishing expectations of a 5.0 print. The decline in both new orders and shipments, states Zero Hedge, “[strongly hints] that a hard-landing recession is inevitable and that, for all the posturing, a Fed rate cut is imminent after all.”

Also worth noting is the fact that the general business conditions index plunged 42 points to -31.3, the second largest monthly decline on record; only 12% of respondents reported that conditions had improved over the past month, with 42% saying they had worsened.

Not your father’s stagflation

Historically high US inflation, combined with consecutive Fed interest rate hikes, have prompted a number of commentators to compare today’s situation with 1980, particularly whether both periods are stagflationary. In fact they differ for a number of reasons.

Before exploring the differences, the first question to address is whether the economy is destined to fall into stagflation. In April Sunshine Profits presciently wrote:

The US economy is likely to shift from an economic recovery to stagflation in the upcoming months. Even the Fed itself admits that inflation will jump this year. Of course, the central banks are trying to convince us that inflation will be only transitory, but it’s possible that they underestimate the inflationary risk and overestimate their ability to deal with it.

In fact this is precisely where we are now. The World Bank admits that the risk of stagflation is getting better and more real, stating in its latest report, ‘Global Economic Prospects’, that “stagflation risks are rising amid a sharp slowdown in growth.” The institution reduced its global growth forecast from 5.7% in 2021 to 2.9% in 2022, significantly lower than the 4.1 % predicted in January. Furthermore, the World Bank projects world GDP will slow by 2.7 percentage points between 2021 and 2024 — more than twice the deceleration between 1976 and ’79.

In the report’s foreword, World Bank President David Malpass was surprisingly cavalier, stating that the risk of stagflation is now, and that it could persist well into the future:

Amid the war in Ukraine, surging inflation, and rising interest rates, global economic growth is expected to slump in 2022. Several years of above-average inflation and below-average growth are now likely, with potentially destabilizing consequences for low- and middle-income economies. It’s a phenomenon—stagflation—that the world has not seen since the 1970s (…).

The danger of stagflation is considerable today (…). Subdued growth will likely persist throughout the decadebecause of weak investment in most of the world. With inflation now running at multidecade highs in many countries and supply expected to grow slowly, there is a risk that inflation will remain higher for longer than currently anticipated.

Wow. And that’s coming from the World Bank, a notoriously cautious, conservative institution. Let’s review. For stagflation to occur in the United States, the world’s largest economy, three elements need to occur simultaneously: growth that is slowing or stopped; high unemployment; and high inflation. As stated above, the first two quarters saw negative economic growth, which is the classic definition of a recession. The July inflation reading was 8.5%, lower than 9.1% in June but still at multi-decade highs. The employment picture in the US is admittedly good but there are reasons for concern. Though the unemployment rate is at a 50-year low of 3.5%, jobless claims last week rose to a new 8-month high. The Labor Department reported the number of Americans who signed up for unemployment benefits hit the highest level since November.

“Initial claims and continuing claims have inched higher for the last four months and suggest that the labor market will likely slow further throughout the back half of this year,” Jeffrey Roach, chief economist for LPL Financial, said in a note quoted by CBS News.

We may not have reached 1980-level stagflation, but we’re getting there. The question is how it differs from previous incarnations. Economist Nouriel Roubini suggests it is similar, but worse.

In a commentary on the subject, Roubini begins with a bold statement: The world economy is undergoing a radical regime shift. The decades-long Great Moderation is over.

By Great Moderation, he means a period of low inflation in advanced economies following the high inflation and severe recessions of the late 1970s and early 1980s. This period was also characterized by stable, robust economic growth, with short and shallow recessions; low and falling bond yields; and sharply rising stock prices. Emerging-market economies like China and Russia became more integrated in the world economy, supplying it with low-cost goods. Migration from the (poorer) Global South to the (richer) Global North helped keep a lid on wages.

The Great Moderation started to come apart during the 2008 financial crisis and then during the 2020 covid-19 recession. Now, Roubini argues, inflation is back, due to a number of supply and demand factors. These include:

- A backlash against globalization creating opportunities for protectionist politicians; along with restrictions on immigration, trade and movement of capital;

- Anger over wealth and income inequalities leading to government policies that support workers, including rising wages that are contributing so spiraling wage-price inflation;

- The balkanization of the global economy, something we have written about, which is deeply stagflationary;

- Geopolitical turmoil such as the war in Ukraine which is disrupting the trade of energy, food, fertilizers, industrial metals, and other commodities.

- A weaker dollar that accompanies the loss of US global status would also be inflationary, as is climate change, due to droughts and floods destroying crops and leading to higher food prices; and future pandemics, which as we have seen, can result in hoarding of critical supplies of food, medicines and essential goods.

- Demands for decarbonization have led to under-investment in fossil-fuel capacity, making the current energy crisis inevitable.

- On the demand side, Roubini mentions loose and unconventional (read “QE”) monetary and fiscal policies that “have not become a bug but rather a feature of the new regime”. These policies are highly inflationary. From the start of pandemic-related government spending in the spring of 2020, to today, the US government has printed over $6 trillion. During that period, the US money supply increased by 41%, with the Fed’s actions amounting to the biggest monetary explosion that has ever occurred in the 227 years since the founding of the United States.

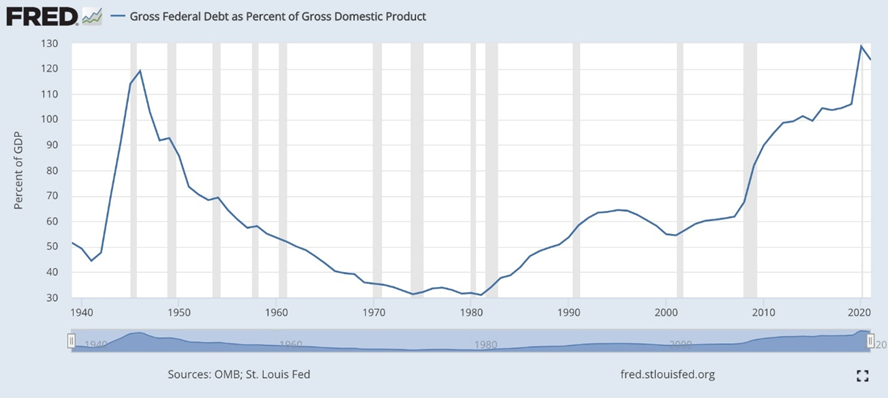

The latter is a key point because it marks an important difference between the current stagflation and that of the early ‘80s: the debt.

Gorging on debt

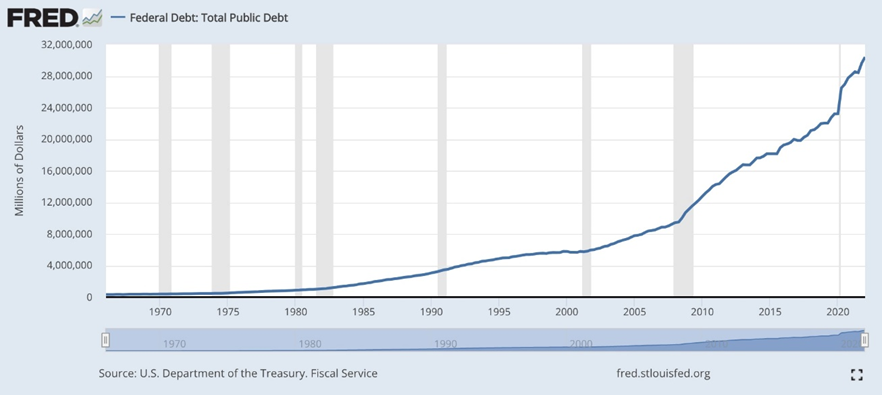

According to the FRED chart below, the US debt to GDP ratio in the ‘70s was around 35%. Today it is three and a half times higher, at 123%.

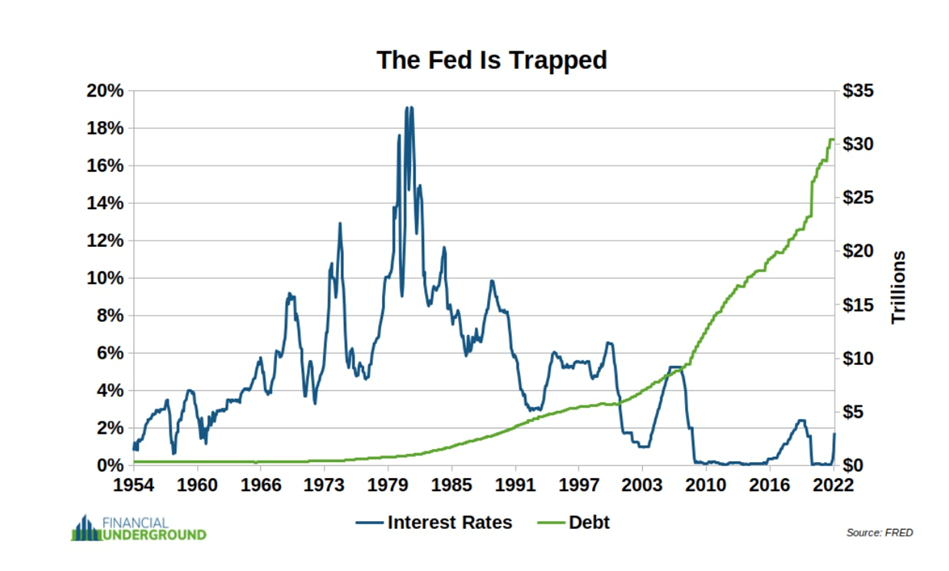

This severely limits how much and how quickly the Fed can raise interest rates, due to the amount of interest that the federal government will be forced to pay on its debt.

The national debt has grown substantially under the watch of Presidents Obama and Trump. When Trump was handed the keys to the White House in January 2017, the national debt stood at nearly $20 trillion. When he left, in Q1 2021, it was at $28.1T. Since the end of 2019, the debt has surged about $7 trillion, with over half of that consisting of money borrowed to pay for covid-19 relief programs.

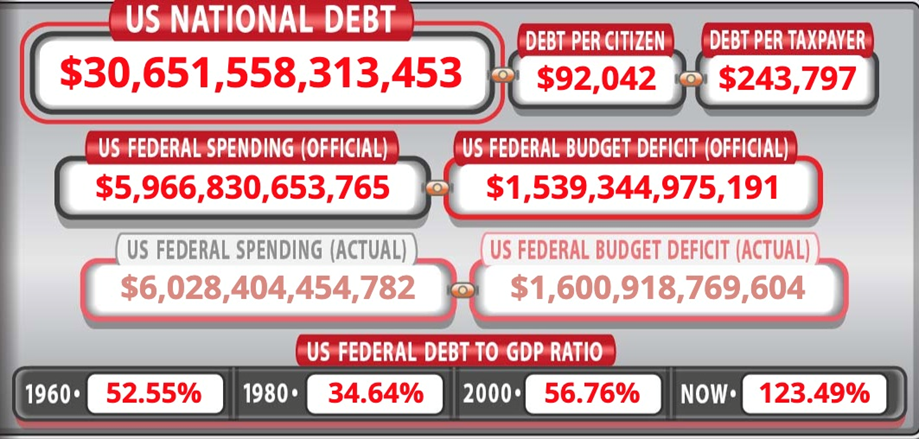

Each interest rate rise means the federal government must spend more on interest. That increase is reflected in the annual budget deficit, which keeps getting added to the national debt, now standing at a gob-smacking $30.6 trillion.

We are talking about interest costs approaching a trillion dollars per year, about a quarter of the $4 trillion in revenues the federal government takes in annually. That’s insane.

Higher debt servicing costs take away from other spending that that will have to be cut, as the government tries to keep its annual budget deficit under control.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) — both reliable sources — project a deficit of $1.3T in 2022, and every year until 2031. This, plus the interest on the debt, severely constrains the Fed’s policy options. It needs to raise interest rates, to quell inflation, but going too far risks slamming the brakes on the economic recovery.

Roubini agrees that Between today’s surging stocks of private and public debts (as a share of GDP) and the huge unfunded liabilities of pay-as-you-go social-security and health systems, both the private and public sectors face growing financial risks. Central banks are thus locked in a “debt trap”: any attempt to normalize monetary policy [i.e. increase interest rates] will cause debt-servicing burdens to spike, leading to massive insolvencies, cascading financial crises, and fallout in the real economy.

What is the connection between spiraling debt and stagflation? Doug Casey in his blog ‘International Man’ explains it thus:

The US federal government’s deficit spending and debt are the most significant factors driving this money printing, resulting in drastic price increases.

The US federal government has the biggest debt in the history of the world. And it’s continuing to grow at a rapid, unstoppable pace.

It took until 1981 for the US government to rack up its first trillion in debt. After that, the second trillion only took four years. The next trillions came in increasingly shorter intervals.

Today, the US federal debt has gone parabolic and is well over $30 trillion.

If you earned $1 per second, it would take over 966,484 YEARS to pay off the US federal debt…

The amount of federal debt is so extreme that even a return of interest rates to their historical average would mean paying an interest expense that would consume more than half of tax revenues. Interest expense would eclipse Social Security and defense spending and become the largest item in the federal budget.

Further, with price increases soaring to 40-year highs, a return to the historical average interest rate will not be enough to reign in inflation—not even close. A drastic rise in interest rates is needed—perhaps to 10% or higher. If that happened, it would mean that the US government is paying more for the interest expense than it takes in from taxes.

In short, the Federal Reserve is trapped.

Raising interest rates high enough to dent inflation would bankrupt the US government.

Rising inflation also affects investors, many of whom have allocated their stocks and bonds to a 60-40 split, where 60% of investments are in higher-return but volatile stocks, and 40% are in lower-return but more stable bonds.

When inflation rises, returns on bonds become negative (yield minus rate of inflation) because rising yields led by higher inflation expectations reduce their price (yields and bond prices move in opposite directions). Inflation is also bad for stocks, because it triggers higher interest rates. The higher cost to borrow often dents corporate earnings.

In another Project Syndicate article, Roubini states that, should inflation remain well above the Fed’s 2% target, long-term bond yields (the US 10-year Treasury, 20-year and 30-year) would go much higher, and equity prices could end up in bear country (a fall of 20% or more).

More to the point, if inflation continues to be higher than it was over the past few decades (the “Great Moderation”), a 60/40 portfolio would induce massive losses. The task for investors, then, is to figure out another way to hedge the 40% of their portfolio that is in bonds.

One way is to invest in inflation-indexed bonds, where the principal is indexed daily to inflation or deflation, thus hedging the bond’s inflation risk.

Another option is to buy gold, the world’s oldest, and arguably, the best inflation hedge because gold bullion, unlike fiat currencies, tends to rise in price as inflation drifts higher.

Stagflation and gold

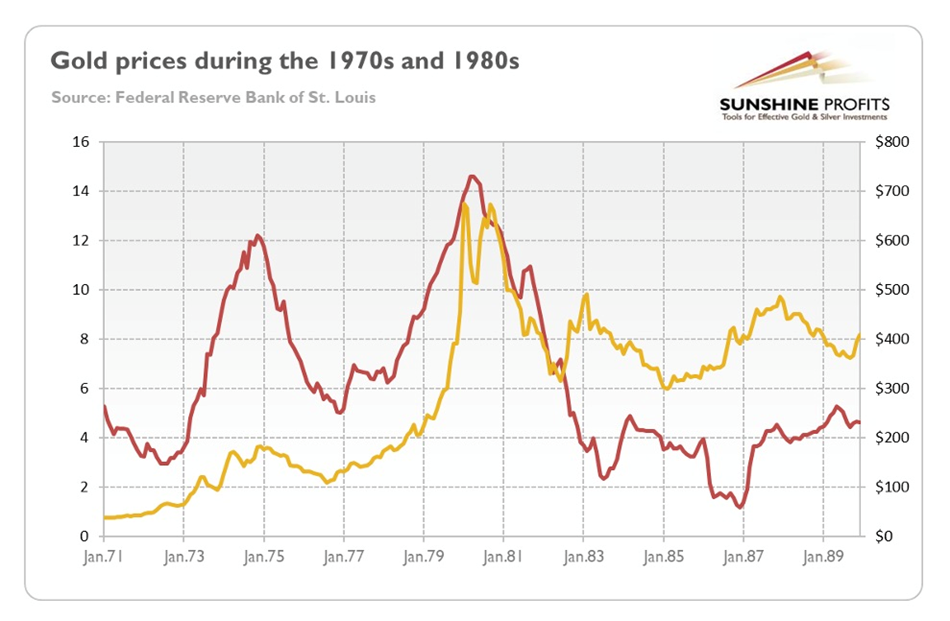

How has gold done during stagflation? As it turns out, quite well. The chart below by Sunshine Profits shows the gold price climbing during the stagflationary 1970s, surging from $100 per ounce in 1976 to around $650 in 1980, when CPI inflation topped out at 14%.

In fact, gold outperforms other asset classes during times of economic stagnation and higher prices. The table below shows that, of the four business cycle phases since 1973, stagflation is the most supportive of gold, and the worst for stocks, whose investors get squeezed by rising costs and falling revenues. Gold returned 32.2% during stagflation compared to 9.6% for US Treasury bonds and -11.6% for equities.

Simply put, goes does well in stagflationary environments because it benefits from the elevated risk environment, high inflation and falling real interest rates (interest rate minus inflation). Although nominal interest rates have been climbing since March, real rates remain negative because inflation is so high. (Right now 2.5% – 8.5% = -6.0%).

According to the World Gold Council, the risk of stagflation has increased materially since it addressed the topic last year, with Europe more endangered than the US due to its vulnerability to skyrocketing natural gas prices. Also, the continent’s recovery from the pandemic has been more service-driven than goods-driven. The region relies highly on manufacturing so a service-led recovery has less impact. The European Central Bank reportedly discussed the possibility of a stagflationary shock.

Yamana Gold’s CEO Peter Marrone was obviously talking his book when he told Kitco’s David Lim at the 2022 PDAC convention in Toronto, that we are on the “cusp of a recession”, with certain stagflation breeding a perfect storm for gold’s price to rise. He noted the parallels between 1980 and today including looming recession and Russian aggression; in 1980 the Russians invaded Afghanistan, in 2022 it was Ukraine.

“In the context of [what was happening in 1980], gold’s price went to around $840 per ounce,” he said. “In terms of adjusted dollars, what does $840 mean today? That number is roughly $2,700-$2,800. And I certainly think that there is an excellent opportunity for gold’s price to go up to those levels again.”

Marrone also said the Fed’s hawkish moves, in raising interest rates by 75 basis points at its last two meetings, are likely to relent.

“There are very limited things that central banks can do, as a result of what’s causing this inflationary pressure, supply chain disruptions,” he explained. “… Worldwide debt is at unprecedented levels… And worldwide economies are shrinking. It seems to me that we’re in this perfect storm where it becomes very difficult for central banks, including the Fed, to increase interest rates to a level that would tame inflation. At some point they probably have to pull back or come to the conclusion that inflationary pressures are here to stay for longer than anticipated.”

Sunshine Profits also referenced the debt when they noted in June that the debt levels are much higher than the stagflation of the 1970s and ‘80s, meaning that the Fed’s tightening cycle could be potentially even more harmful now.

Analysts at Incrementum AG, an asset management company based in Lichtenstein, say that, while the gold market remains off its first-quarter highs of around $1,840/oz, it expects the precious metal to rally to above $2,000 by year’s end.

In their annual In Gold We Trust report, released in May, the analysts are bullish on gold as rising inflation threatens to push the global economy into a recession and create a stagflationary environment of low growth, high inflation and rising unemployment.

They point out that, of the Federal Reserve’s last 20 tightening cycles, only three have not ended in a recession, and that the Fed is overestimating the impact of rate hikes and balance sheet reductions (“quantitative tightening”) on containing inflation.

Also of interest, is the fact that Incrementum agrees with economist Nouriel Roubini about stagflation’s potential for destroying the wealth of investors holding a “60-40” stocks to bonds portfolio. They note this structure is expected to see negative returns for only the fifth time in 90 years, and that with inflation likely to hold above 5% through 2022, stock markets could book further losses this year.

Like Marrone, the Incrementum analysts believe that, while interest rates are probably heading higher, they don’t expect this trend to be sustainable as the global economy slows and market liquidity dries up.

“As soon as the Federal Reserve is forced to deviate from its planned course, we expect the gold rally to continue and new all-time highs to be reached. We believe it is illusory that the Federal Reserve can deprive the market of the proverbial “punchbowl”for any length of time, and we seriously doubt that the transformation of doves into hawks will last,” the analysts said via Kitco. “If the downward trend on the stock and bond markets that has persisted since the beginning of the year continues, a brash counter-reaction by the Federal Reserve seems to be only a matter of time.”

Conclusion

Let’s get back to the objective of raising interest rates, which is to cool demand, in an economy where, for several months now, demand for goods and services has outpaced supply, causing inflation.

However, the Fed can raise rates as high as they want, the problem is they are not going to magically increase the supply of a number of commodities and manufactured goods we are running short of.

A big part of the current inflationary cycle, the worst since the early 1980s, is “supply-side” inflation. This has nothing to do with killing demand, and everything to do with increasingly supply. The Fed can’t control supply-side inflation, and they know it.

In fact the Fed’s mandate of raising interest rates to “destroy” demand, is running up against the policy of several governments around the world who are committed to upgrading their aging infrastructure and fulfilling a massive shift to electrification and decarbonization, so-called “green infrastructure” investments. (read more here)

China, the world’s biggest commodities consumer, plans to spend at least US$2.3 trillion this year alone, on thousands of major projects, according to Bloomberg. They are part of Beijing’s most recent Five-Year Plan that calls for developing “core technologies” including high-speed rail, power infrastructure and new energy. Translation: more money will be aside in years two to five.

China’s $900 billion “Belt and Road Initiative” is designed to open channels between China and its neighbors, mostly through infrastructure investments. Dozens of countries have signed up to it, including Russia.

The United States is pursuing its own $1.2 trillion infrastructure package, to be spent on roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, among many other items.

Between China, the United States, Europe and Japan, we are talking about $2.3 trillion + $1.2 trillion + $600B + $900B = $5 trillion in infrastructure commitments. Among the materials likely to be highly demanded for these projects, are steel, rebar, aluminum, cement, sand and gravel. There will also be large amounts of copper required for wiring and plumbing, nickel-containing stainless steel reinforcement on bridges, zinc coatings used as corrosion protection for steel bridges, etcetera, etcetera, the list of metals goes on.

For China’s Belt and Road Initiative alone, the International Copper Associates estimates the demand for copper in over 60 Eurasian countries, could hit 6.5 million tonnes by 2027, a 22% increase from 2017 levels.

Then there’s the electrification and decarbonization imperative.

Population explosion and urbanization, particularly in Asia and Africa, are macro demand factors pressuring supply. Climate change and resource nationalism are also throwing up impediments to bringing promising mineral deposits into production or expanding existing ones.

On top of all this, we have a food crisis, of sharply higher prices brought about by the war in Ukraine, where the Russians blockaded ports, that have only recently re-opened, but also long-running droughts in some of the world’s breadbaskets including the US Midwest.

Dumb government policies like mandated reductions in fertilizer-related emissions (read more here), threaten to reverse the Green Revolution that has fed billions and nearly eradicated famine.

The winds of recession are blowing and the result could be a perfect storm for the Great Stagflation 2.0, of hyperinflation, stalled economic growth and a return to joblessness.

The World Bank has admitted that the risk of stagflation is not sometime in the future but right now; the institution projects world GDP will slow by 2.7 percentage points between 2021 and 2024 — more than twice the deceleration between 1976 and ’79.

Among the recessionary signals that are flashing, are an increase in the Misery Index, falling US regional manufacturing PMIs, an inverted yield curve, and a recent uptick in US jobless claims.

Clearly we aren’t at the level of 1970s stagflation, but we are moving in that direction, egged on by the Federal Reserve which does not seem to understand, or care, that constantly raising interest rates will do very little to stop inflation if measures aren’t also taken on the supply side.

I’m talking about more mining to address metals shortages, more manufacturing to create real, high-paying jobs, and figuring out where to farm to get decent yields crop without destroying the environment.

For the past 30 years or so, after the world economy recovered from the Volcker Fed-induced recession, things have been pretty good. But the Great Moderation is over and we are now into an era of widespread shortages, and massive money-printing to cover the government’s exorbitant spending patterns. I agree with Doug Casey’s assessment that deficit spending and debt are the most significant factors driving this money printing, resulting in drastic price increases.

And it’s not going to stop, because the demands on government keep increasing. Decarbonization & electrification, rectifying countries’ “infrastructure deficits”, and attempting to address the widening gap between rich and poor, are just three demand drivers likely to push government spending and therefore inflation higher.

In sum, when you think about all that is happening to pressure prices — climate change; resource nationalism; NIMBYism regarding new mines in North America & Europe, lower ore grades and poor metallurgy; decarbonization & electrification, hundreds of new mines required to meet battery metals’ demand; malinvestment in mining and oil and gas; money-printing “out the wazoo” to cover annual deficits and government bond purchases (QE), all the pandemic-related stimulus payments to Americans; and the trillions in promised new spending, that hasn’t yet been factored into inflation — there is just no way that the Fed is going to have an impact on inflation. How can it?

The Fed wants to get inflation down from 8.5% to 2%. That’s a huge gap. Also consider that, even if inflation slows, as it appears to be currently, does not mean that consumers get their spending power back. Like compound interest in reverse, inflation is cumulative. (e.g. July’s 8.5% inflation is on top of June’s 9.1%, which is on top of May’s 8.6%, etc.)

Is the Fed really going to keep raising interest rates like the Volcker Fed did in 1981, until it crashes the economy and causes a recession? At AOTH, we believe the Fed will soon pause its rate hikes, when it realizes that the hikes are doing more harm than good, and that “getting to 2%” inflation is completely unrealistic.

When it pivots to lowering interest rates, and other central banks follow suit, we expect gold and silver prices to turn sharply higher.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.