The global infrastructure deficit – the road not yet taken

2019.02.14

Infrastructure is the physical systems – the roads, power transmission lines and towers, airports, dams, buses, subways, rail links, ports and bridges, power plants, water delivery systems, hospitals, sewage treatment, etc. – that are the building blocks, the Legos, that fuel a country’s, a cities or a community’s economical, social and financial development.

There is an undeniable, an unarguable connection between the quality of a countries economic competitiveness and its infrastructure yet both Canada and the US are facing significant infrastructure deficits, meaning the money that is being allocated for upgrades to water lines, sewers, bridges, roads, dams, power plants, public buildings, etc., isn’t enough to cover maintenance let alone replacement costs.

“We cannot build a 21st century economy on 20th century infrastructure—if it’s that good,” Thomas J. Donohue, President and CEO U.S. Chamber of Commerce

In this article we’ll show how dire the North American (Canada and US) infrastructure deficit is, but we’ll go further and talk about how much the deficit is costing us, what metals we need to acquire to address it, and how we might go about finding the means to repair and build our North American infrastructure without the need to import materials from countries that are not our friends.

Canada

Long, bumper to bumper commutes. Crowded trains. Infrequent buses. Bridges that are so old, crossing them is a death-defying experience, dangerous killer highways, billions of gallons of wasted fresh water, an unreliable electrical grid, fire stations so old the roofs leak and the floors are sloping.

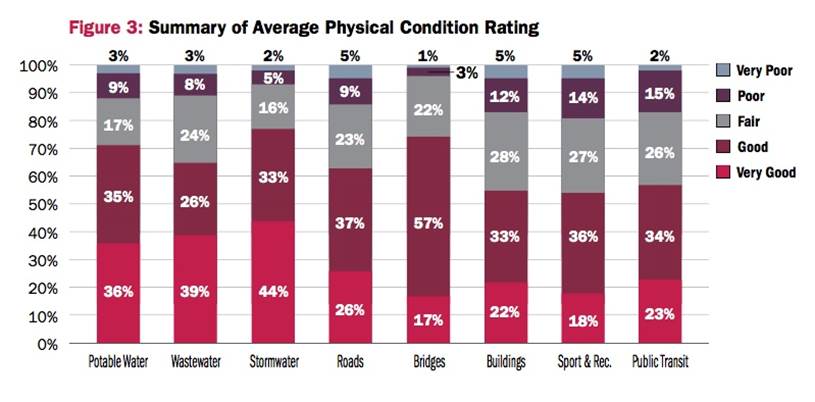

In 2016 the Canadian Infrastructure Report Card rated one-third of municipal infrastructure in fair, poor or very poor condition, and at risk of service disruption.

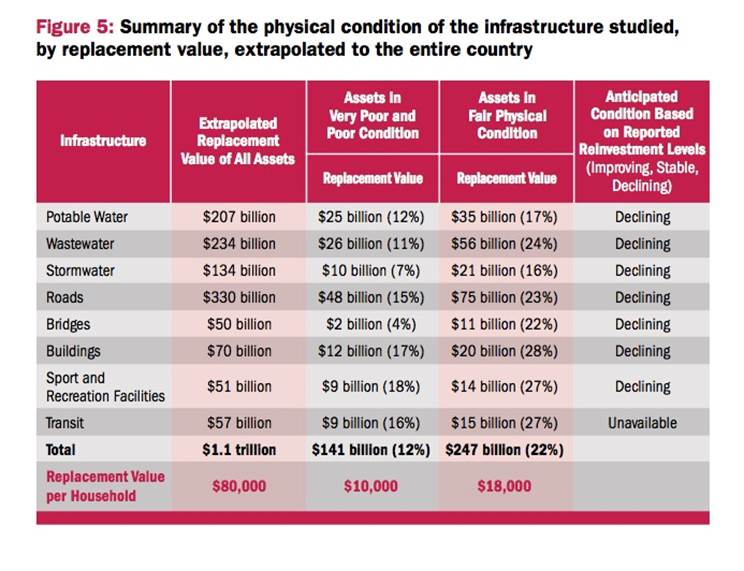

Out of $1.1 trillion in assets, roads and water pipes/ sewers were deemed to be in worst shape. To replace all of it – roads, water infrastructure, bridges, sports and recreation facilities, public buildings and transit – would cost taxpayers $80,000 per household. The table below shows the biggest-ticket items were roads, at $330 billion, and wastewater (sewers, sewer pipes) at $235 billion.

The Federation of Canadian Municipalities says Canada would need to have spent $123 billion over the last few decades to meet current infrastructure needs. With not enough money allocated, the gap is growing by $2 billion a year.

It gets worse. The longer governments wait to rehabilitate aging water pipes, roads, ports etc., the more expensive it becomes, and the more of a risk (or headache) to its users. According to the report card, “Without an increase in current reinvestment rates, the condition of Canada’s core municipal infrastructure will gradually decline, costing more money and risking service disruption.”

CBC suggests the problem lies squarely at the feet of the federal government. Back in the 1950s and ‘60s, Ottawa spent liberally on infrastructure, knowing that capital projects were good for the economy and provided well-paying jobs, along with a higher level of comfort and convenience for a growing middle class. The feds owned nearly half of capital stock like roads and ports, and spent that way too; Ottawa paid around a third of infrastructure spending, municipalities a quarter and the provinces picked up the rest of the tab.

These days, the federal government only covers 13% of infrastructure spending, downloading the majority, 52%, to towns and cities and 35% to provinces and territories. Municipalities can only raise money through property taxes and other relatively minor fees; they’ve constantly got their hand out to the provinces and feds to do up-grades or are forced to partner with the private sector (P3s).

For example, the city of Kelowna, in BC wine country, is reportedly facing a severe infrastructure gap with close to half of its needs over the next 10 years not currently funded. Castanet reports about three-quarters of the $478 billion in unfunded future projects is related to transportation and public buildings.

The problems at First Nations reserves is far from being resolved, despite promises by politicians. The Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships estimates that reserves face an infrastructure gap of about $30 billion; new funding is needed to build 80,000 housing units on reserves.

The Globe and Mail did a study and found that a third of Canada’s 600+ reserves were at risk of producing unsafe water. While Prime Minister Trudeau has vowed to end boil-water advisories by 2021, apparently not much has changed. Just over a year ago Health Canada reported there were 130 advisories in effect in 85 communities compared to 139 in 94 communities the year earlier.

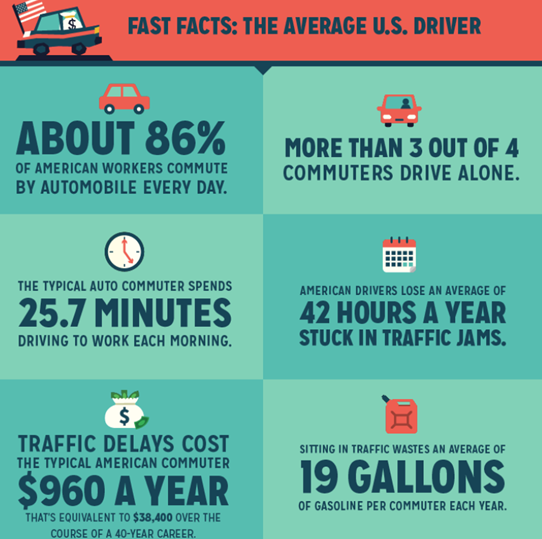

The Canadian Chamber of Commerce said in a report that “Ten thousand years is how much additional time commuters in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver spend stuck in traffic every single year as a result of road congestion from key bottlenecks in those cities.”

Other than frustration, there are real costs of infrastructure-spending neglect. The Globe and Mail reports the Business Council of Canada saying it would require an investment of between $150 million to $1 trillion to make the economy run with optimal efficiency. In other words, not only is the infrastructure deficit risking public safety, and making people’s lives hell, it’s also a major drain on the economy.

The United States

Donald Trump campaigned on a promise “to fix America’s crumbling cities.” Two years later, the decay continues. And like Canada, the US gets a fail on infrastructure spending; the 2017 Infrastructure Report Card scored a D+. At least it wasn’t an F. Since 1998, US infrastructure has consistently earned D averages.

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, over the last four years (when the last report card came out), there has been no improvement in bridges, roads, drinking water, energy, aviation and dams. The society estimates it will take $4.6 trillion by 2025 to bring US infrastructure up to an acceptable standard. As of March 2017 less than half of that spending had been allocated.

Some of the facts in the report card are banal; others are downright frightening. Here are the high (or are they low) points:

- Of the 90,000 dams in the US the average age is 56. By 2025, 70% will be over 50 years old. 15,500 are rated “high hazard potential dams” meaning loss of life is probable if they fail.

- 4 in 10 bridges are over 50, with 56,000 identified as structurally deficient.

- 2 trillion gallons of drinking water are lost every year from water main breaks. Most water mains were built in the early to mid-20th century; the average lifespan is 75 to 100 years ie. past it.

- Most power lines constructed in the 1950s and ‘60s are past their life expectancy. 640,000+ miles of high-voltage lines are at full capacity.

- One out of every five miles of highway is in poor condition.

- Two out of five miles of urban interstates are congested and contributed to about $160 billion in wasted time and fuel.

- Congestion at airports is increasing due to airport infrastructure and traffic control systems not keeping up. Yikes.

Like Canada there are major costs to this funding gap south of the border. The American Society of Civil Engineers warns that not spending enough on infrastructure will cost $3.9 trillion in lost GDP and 2.5 million jobs.

Delays caused by traffic congestion alone cost the economy over $120 billion a year in lost productivity, according to Henry Petroski, author of ‘The Road Taken: The History and Future of America’s Infrastructure’.

According to a 2014 study by researchers at the University of Waterloo in Canada cutting out a daily hour-long commute each way is the equivalent of earning an extra $40,000 a year.

As for infrastructure spending, don’t discount the multiplier effect. The Council on Foreign Relations quotes a University of Maryland study saying that every dollar spent on infrastructure adds up to $3 of GDP growth.

So there you have it. The infrastructure gap and its drain on economic activity reach into the trillions. Two years ago the Trump Administration rolled out a plan to encourage spending on infrastructure at the state and local levels and through private investors, but it was “widely panned for offering no new direct federal spending and never got a vote in Congress. Trump had asked Congress to authorize $200 billion over 10 years to spur a projected $1.5 trillion in projects,” Reuters reported.

After winning back the House of Representatives in November, Democrats planned to ask the White House to back significant additional federal funds for infrastructure. And so Americans wait.

Metallurgical Achilles heel

It seems to me there are two problems here. One is a lack of funding. In Canada the bottleneck is the cities and the provinces. They don’t have the money, and neither, presumably, does the federal government – although the Feds could afford $4.5 billion for a never to be built pipeline. Otherwise they wouldn’t have downloaded most of the infrastructure costs to them. In the US there’s plenty of money in the budget, but most of it goes to Social Security and defense. The close to a trillion dollars a year the American Society of Civil Engineers says it needs for the next five years is there, it just isn’t allocated. To lawmakers there must be other priorities.

The second problem relates to how we source the materials needed for rebuilding Canadian and American infrastructure. The amount of pipe rehabilitation, the number of dams that need to be upgraded, new ports, airports, bridges, power plants etc., will require billions of tonnes of raw materials. We’re talking iron ore, steel, zinc, manganese, vanadium and copper, just to name a few key metals.

Some of these metals are unavailable in the States or Canada. North America has some deposits, but no mines. So we import them.

The US has been locked in a trade war with China for nearly a year. The spat has meant billions in import tariffs from either side. Canada was drawn into the dispute recently through a request to extradite the CFO of Huawei, a Chinese company specializing in 5G technology.

We think we can just get the metals needed for these huge infrastructure build-outs from places like China, Russia, South Africa, the DRC and Gabon, but these countries aren’t reliable and in the case of the first two, they have shown they are not friendly to the West.

Most people don’t know it, but Canada and the US are dependent on foreign countries for a number of critical metals. Why is all of this important? Security of supply. Without a reliable supply chain, a country must depend on outsiders. This gives foreign suppliers incredible leverage over North Americans. There is always the possibility of slowed flows or bans on strategic materials, due to politics or trade disputes – a perfect example is Saudi Arabia’s threat to slow or stop oil production if sanctioned over the Khoshoggi affair, another current example is the ongoing trade dispute with China.

The US is dependent on South Africa, the politically unstable Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and an increasingly unreliable and aggressive China for over half of its supply of what it considers strategic or critical minerals.

South Africa has flirted with the idea of nationalizing its mines. It was a hot topic among the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) back in 2010-11. The radical leftist party Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) will nationalize all mines if elected in 2023 according to its recently released party manifesto.

And former President Jacob Zuma said five months ago that the country should nationalize land, banks and mines.

South Africa has also passed Mining Charter III, including resource nationalism-tinged regulations that specify local content requirements.

The 1981 report ‘A Congressional Handbook on U.S. Minerals Dependency/Vulnerability’ singled out eight materials “for which the industrial health and defense of the United States is most vulnerable to potential supply disruptions” – chromium, cobalt, manganese, platinum group metals (ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, and platinum), titanium, bauxite/aluminum, columbium, and tantalum. The first five have been called “the metallurgical Achilles’ heel of our civilization.”

In 1992 Congress directed that the bulk of the strategic and critical materials the US had been able to accumulate in the National Defense Stockpile be sold.

According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), in 1999 the United States was at least 50% dependent on a foreign source for 27 out of the 100 materials covered in its publication ‘Mineral Commodity Summaries’. By 2013, this number had grown to 41 materials out of 100.

Among the minerals and elements the US is import-dependent on, are lithium and rare earths.

In 2008 the National Research Council saw lithium as potentially becoming a critical mineral due to the expected growth of hybrid vehicle batteries. Two years later the US Department of Energy’s Critical Materials Strategy included lithium as one of 16 key elements. The country currently imports most of the lithium that it consumes – with import reliance today pegged at greater than 70%. Lithium is among 23 critical metals President Trump has deemed critical to national security and he signed a bill that would encourage the exploration and development of new US sources of these metals.

‘Critical’ metals for infrastructure

Aside from iron, manganese is the most essential mineral in the production of steel. You can’t produce steel without adding 10 to 20 pounds of manganese per ton of iron. Which makes manganese the fourth largest traded metal commodity.

Both Canada and the United States have numerous and vast iron ore deposits, yet neither country produces manganese.

Vanadium, a soft, silvery gray metal, is the 22nd most abundant element in the Earth’s crust. Vanadium has remarkable characteristics which give it the ability to make things stronger, lighter, more efficient and more powerful. Adding small percentages of it to steel and aluminium creates exceptionally ultra high-strength, super-light and more resilient alloys.

Rare earths are used in a variety of industrial applications. Updating Internet speeds to 5G using fibre-optics requires erbium for the fiber. Computers that will go into new schools and public buildings contain europium. REEs are used in metallurgy as an alloying agent to desulfurise steels, as a nodularising agent in ductile iron, and as alloying agents to improve the properties of superalloys and alloys of magnesium, aluminium and titanium.

Remaining dependent on external, potentially hostile countries for these metals is not such a great idea.

What about the metals, important for infrastructure, that North America does mine?

As producers of copper, iron ore, steel and aluminum, does this not free us from the influence of foreign powers? It does help that we have the capacity to mine these metals. But base metals supply is getting tight, particularly for copper, zinc and lead. How long will our mines last, and we have to turn to “the big boys”? Chile for copper, Australia for iron ore, China for zinc and lead?

Copper

Copper is used for electrical applications because it is an excellent conductor of electricity. That, combined with its corrosion resistance, ductility, malleability, and ability to work in a range of electrical networks, makes it ideal for wiring. Among electrical devices that use copper are computers, televisions, circuit boards, semiconductors, microwaves and fire prevention sprinkler systems.

In telecommunications, copper is used in wiring for local area networks (LAN), modems and routers. The construction industry would not exist without copper. The red metal is also used for potable water and heating systems due to its ability to resist the growth of water-borne organisms, as well as its resistance to heat corrosion.

The market is extremely bullish on copper. As we wrote in The coming copper crunch, by 2035, without major new mines up and running to replace the ore that is being depleted from existing copper mines, we are looking at a 15-million-tonne supply deficit by 2035. Four to six million tonnes of added capacity are needed by 2025.

That’s around the same time the American Society of Civil Engineers hopes that the US will be spending the last of the nearly $5 trillion it earmarks for infrastructure between now and then. But if the copper price has gone up to $10 a pound on supply constraints, the great big infrastructure spend is going to grind to a halt.

Zinc

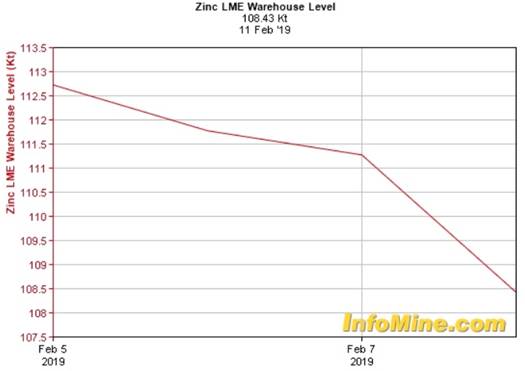

Zinc’s fundamentals are solid. Despite trade war concerns – zinc is mostly used in steel fabrication to prevent rusting – demand growth is expected to keep pace at 2-3%. Some very large zinc mines have been depleted and shut down in recent years, with not enough new mine supply to take their place.

The closed mines represent an estimated 10 to 15% of the zinc market. On the flip side, there have been few discoveries or big zinc projects planned. This is setting the zinc market up for a supply shortage. We can see it already in depleted zinc inventories at LME warehouses.

Canada and the US aren’t big zinc miners. Between them they produce about as much as Australia, the fourth-largest zinc producer. A supply shortage means prices will rise, hurting North American steel fabricators. That galvanized steel suspension bridge needed to replace one built in the 1960s suddenly got a whole lot more expensive.

Mine it here

We need to decide, are we going to stay dependent on foreign countries with asymmetrical interests to our own such as China, South Africa and Russia, or are we going to become independent, by mining and processing metals ourselves, here in North America? Thus gaining full control over our infrastructure needs?

There is even the possibility of cutting the costs of new buildings, hydroelectric facilities and the like by sourcing all of the minerals domestically. Imagine a new dam built entirely with Canadian cement, copper and steel, a galvanized steel bridge made with US zinc, or installing a new fibre optic network into a neighborhood using rare earths sourced from a mine in BC?

It sounds great, but if we’re going to mine domestically, some changes would have to be made to the unreasonably long permitting process, particularly in the US. A 2015 study commissioned by the National Mining Association found that duplicate processes can delay mining projects for a decade or more and that federal and state permitting regulations are hindering the mining industry’s ability to meet minerals demand.

The onerous delays are also hurting the ability of US miners to compete. It takes seven to 10 years to get a mine permitted in the United States versus three to five years in Australia.

Some projects lost up to half their value while awaiting state or federal approval, according to the study. North American mining and mineral exploration should be looking to follow the example set by Sweden.

A key advantage of exploring in Sweden is the short permitting process. Where permitting can take years in other jurisdictions, in Sweden it can be a matter of months, if all the i’s are dotted and t’s crossed. The environmental laws are well-defined.

Conclusion

How can we marry the need to replace aging infrastructure with reducing our North American dependence on critical metals and base metals like copper and zinc, that are likely to become more expensive in coming years due to supply shortages?

The answer is to mine it here.

We already know that building new infrastructure has a multiplier effect in terms of the economic activity it creates. Remember the University of Maryland study: every dollar spent on infrastructure adds up to $3 of GDP growth.

We also know that mining is a big employer. South Africa built an economy around diamond and gold mining. Mining and processing metals like manganese, zinc, rare earths and aluminium could become the lynchpin for a new infrastructure-focused economy. It’s also the right thing to do – creating local jobs and repairing our decaying cities to boot, making Canada and the US stronger, more independent, and better able to compete internationally.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd is on Twitter

Ahead of the Herd is now on FaceBook

Ahead of the Herd is now on YouTube

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.