The Fed option nobody is talking about

2022.06.03

History tells us that previous Fed rate hikes to deal with uncomfortably high inflation resulted in recessions.

During the 1970s, consumer price inflation averaged 7%. To tackle it, then-Fed chair Paul Volcker dramatically raised interest rates. From 11.2% in 1979, Volcker and his board of governors through a series of rate hikes increased the federal funds to 20% in June 1981. This led to a rise in the prime rate to 21.5%, which was the tipping point for the recession to follow, lasting two years.

Let’s also remember what happened when the Fed tried to raise interest rates in 2018. They only got to 2% when the stock market tanked, prompting them to reverse course, and re-instate low interest rates.

Now, the question on most people’s minds is, how aggressive will the Fed be in raising interest rates to fight inflation?

Three options

At its May 3-4 meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee decided to hike interest rates by 50 basis points (0.5%), pushing the federal funds rate to between 0.75% and 1%. The increase was the largest the FOMC has instituted since May, 2000, showing just how dovish (low interest rates) US monetary policy has been for the last two decades.

According to CME Group data, current market pricing has the rate jumping to 2.75-3% by year’s end. Can the economy handle that kind of an increase, after so many years at near zero?

“Inflation is much too high and we understand the hardship it is causing. We’re moving expeditiously to bring it back down,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said during a news conference, in early May.

But while the markets expect the central bank to continue raising rates aggressively over the next few months, Powell said a 75 basis-point increase in June “is not something the committee is actively considering.”

In fact, the most recent news has Fed watchers predicting the organization will pause its monetary tightening in September, if US economic conditions worsen and inflation subsides.

“We have recently seen a tenuous but remarkable change in Fed communications, where some Fed officials suggest the option of downshifting or pausing later in the year as they reach 2% given the challenging macro backdrop, tightening of financial conditions, and potentially softening inflation,” Reuters reported Bank of America analysts stating on March 26, two days after the minutes from the FOMC’s May 2 meeting were released.

The minutes showed the Fed grappling with how best to reduce inflation, which by its measure is running at more than three times the Fed’s 2% target, without causing a recession or pushing unemployment higher by lifting interest rates too much.

In summary, the Fed has two options when it comes to interest rate increases designed to tackle the highest US inflation in 40 years.

The first is the Fed continues to hike rates, beyond what the economy can handle, causing a recession, defined as two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth.

The recession chatter picked up around Easter, when Goldman Sachs published a report putting the odds of a recession at about 35% over the next two years. The influential investment bank noted that 11 out of 14 tightening cycles in the US since World War II have been followed by a recession within two years.

Bloomberg wrote, The consensus is that the Fed is so far behind that curve when it comes to increasing rates that it will have no choice but to tighten monetary policy so severely that it forces the economy to contract to get inflation under control.

In the second option, the Fed stops raising rates (the “pause”) for the time being. Under this scenario, the central bank could even reverse course, like it did in 2018, and return to lowering interest rates and its monthly purchases of bonds and mortgage-backed securities, a policy known as “quantitative easing”, or QE.

The result, imo, of either option is stagflation, a particularly nasty combination of high, persistent inflation, stagnant growth and soaring unemployment, as the economy implodes under central banks failed efforts to control inflation.

The US economy stagflated during the financial crisis of 2007-10 but the more memorable period was in the late 1970s, early ‘80s. In November 1979 the price of West Texas Intermediate crude surpassed $100 per barrel and hit $125 the following April, a level that would not be exceeded for 28 years.

The annual rate of inflation peaked at 14.8% in 1980 as it hit the second highest level on record; the unemployment rate was 8.5%.

Shortages across a wide spectrum of commodity groupings is the main reason we believe that inflation is not transitory. Not the result of pandemic-related supply disruptions, as Powell and others tried to argue (unsuccessfully, they have since dropped the term), but rather, an embedded fixture of the economy likely to last several years.

Food

Globally, food prices have been soaring all year, with the FAO Food Price Index reaching a record high in March. This is after prices jumped 28% in 2021, the highest in a decade.

The ongoing war in Ukraine is a major disruptive force in the global food market, in particular for wheat, corn and sunflower oil. About 25% of all global wheat exports are through Ukraine. Russia is also a major producer of agricultural products, as well as a top exporter of nitrogen fertilizers.

The cost of raw materials in the fertilizer market — ammonia, nitrogen, nitrates, phosphates, potash and sulfates — has gone up by 30% since the start of 2022. Their prices have now exceeded those seen during the food and energy crisis in 2008, according to British commodity consultancy CRU.

As the price of fertilizers continues to rise, so will our food products, as farmers around the world are forced to cut their fertilizer use.

A direct consequence of soaring fertilizer prices is the threat of declining food production, as well as quality, in many parts of the world. In the Philippines, where urea (a key nitrogenous fertilizer) is now about 3,000 pesos (about $57) per bag, crop yields could drop by as much as 10%. In Peru, staples such as rice, potatoes and corn could tumble as much as 40% unless more fertilizer becomes available. In Brazil, the world’s biggest soybean producer, a 20% cut in potash use could bring a 14% drop in yields, while in In West Africa, falling fertilizer use will shrink this year’s rice and corn harvest by a third.

Energy

The culprit behind skyrocketing fertilizer and food costs is natural gas, used as a raw material to produce ammonia, the building block for all nitrogen fertilizers, which account for most of the world’s fertilizer consumption. Typically 60-80% of production costs are natural gas.

Last week, US benchmark NG prices hit $9 per million British thermal units (MMbtu) for the first time since 2008, fueled by record LNG exports and unseasonably high demand for electricity. Prices have surged 130% so far this year, due to strong demand for LNG in Europe, which is scrambling to replace Russian gas the continent relies on for 40% of its gas supply, Oilprice.com reported. Early heat waves in the US that began at the start of May have also boosted demand for air conditioning and power generation.

WTI, the US crude oil benchmark, has climbed 45% since the beginning of the year, including a 13-year high of $130/barrel reached on March 6 following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Climate change

On top of soaring farm input costs and the war in Ukraine, another important factor driving food inflation is climate change.

In 2018 the world’s leading climate scientists warned there are only 12 years to go for warming to be kept to a maximum 1.5 degrees C. If, after a dozen years, not enough is done to slow global warming, a tipping point will be reached, beyond which the risk of droughts, floods and extreme heat, will significantly worsen.

How are we doing with that? Not so great. One only has to look at regional climate/ weather maps to see that major changes are taking place before our very eyes.

Despite the promises of politicians who claim to have the answers to global warming, the truth is it is unstoppable. The world will keep warming until it starts cooling. We are all on an upward global warming escalator that has no down option. The only question is, how fast will the escalator move?

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would reduce average wheat yields by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

Extreme heat and temperature fluctuations are hard on plants. Heavy rains on parched ground cause flooding, which can devastate crops and livestock, accelerate soil erosion and pollute water.

Droughts are exacerbated by rising temperatures, reduce crop yields and cause irrigation water shortages. Crops near coastal areas can also be ruined by saltwater intrusion, the result of storm surges or rising seas.

We know from multi-year measurements that mountain glaciers are in retreat. Over the last few decades, almost all the world’s glaciers have shrunk and the rate of decline is accelerating.

Russia is among the countries most likely to be impacted by rising temperatures. Much of its oil and gas pipeline infrastructure is sitting on permafrost and nearly all of its oil & gas fields are under permafrost. Most of the Russia’s nickel mines are in the Arctic. The ground is thawing, threatening to unlock millions of tonnes of methane and CO2, serious diseases like anthrax, and to topple buildings, break pipelines, and damage roads, bridges and railways.

Repairing it is going to be very expensive. If oil and gas continues to be usurped by renewable energies and electric vehicles, the transition will diminish Russia’s ability to pay. So far the country’s leadership hasn’t shown itself up to the task of rebuilding/ relocating its infrastructure to safer ground.

Metals

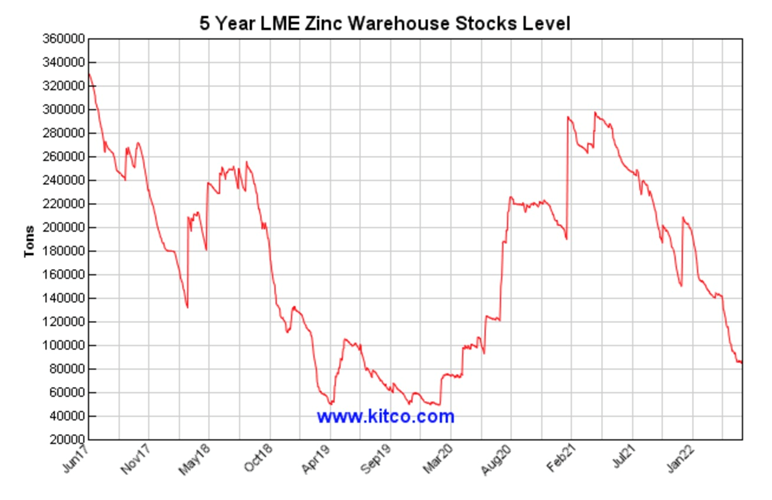

Bloomberg reported in April that inventories across London Metal Exchange warehouses “dropped to perilously low levels, raising the threat of further spikes in everything from aluminum to zinc.”

Available stockpiles across the six contracts on the LME were at their lowest levels since 1997.

Goldman Sachs warned that copper is “sleepwalking towards a stockout” and zinc inventories fell more than 60% in under three weeks.

The sharp drop echoed a similar drawdown in copper last year, when stocks of the red metal plunged to their lowest since 1974.

The price of lithium is up more than 400%, as automakers race to secure supplies, expecting a surge in demand for the EV battery ingredient.

Reuters reported on Monday that despite metal prices retreating recently due to slowed economic activity in China, overall stocks in LME warehouses have fallen below 900,000 tonnes, from levels above two million tonnes in January 2021.

Conclusion

In a world of food, metals and energy shortages, a situation that does not appear to be improving due to the continued war in Ukraine and the unstoppable effects of global warming, the smart investment appears to be in commodities.

Commodities are often used as a hedge against inflation. The reason is simple. As demand for goods and services rises, so do their prices, along with the raw materials (commodities) needed to produce the finished products.

As we have pointed out, there are many factors pointing to more expensive commodities. They include the war in Ukraine squeezing oil, natural gas and food supplies, climate change, the fresh water crisis, and resource nationalism.

As countries cue up for raw materials, the already tight markets for industrial metals like copper, nickel, aluminum and zinc, will tighten further. The surge in demand leading to higher prices will prompt countries that have these materials to hold onto them. A wave of resource nationalism will wash over the mining sector.

We are already seeing this happening in Chile, Peru, Indonesia, the DRC, and even the United States, which has made a number of recent anti-mining decisions, and wants to increase mineral royalties.

We don’t know what the Federal Reserve will do regarding its quest to control inflation — whether it continues raising rates or decides to pause them and return to quantitative easing. But it doesn’t really matter. To us the bottom line is that commodities are the right place to be invested. With limited gains made over the past two years, precious metals look to be particularly undervalued, and that’s why we at AOTH are heavily weighted towards gold and silver.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

decides to pause them and return to quantitative easing. But it doesn’t really matter. The bottom line is that commodities are the right place to be invested. With limited gains made over the past two years, precious metals look to be particularly undervalued, and that’s why we at AOTH are heavily weighted towards gold and silver.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.