The evisceration of the middle class – Richard Mills

2022.11.17

“This American carnage stops right here and stops right now,” President-elect Donald Trump thundered during his inaugural address in January, 2017.

Indeed the stats were alarming. Crime in US cities was off the charts, with Chicago suffering a 59% increase in homicides. Murders were up 56% in Memphis, 61% in San Antonio, 44% in Louisville, 36% in Phoenix and 31% in Las Vegas.

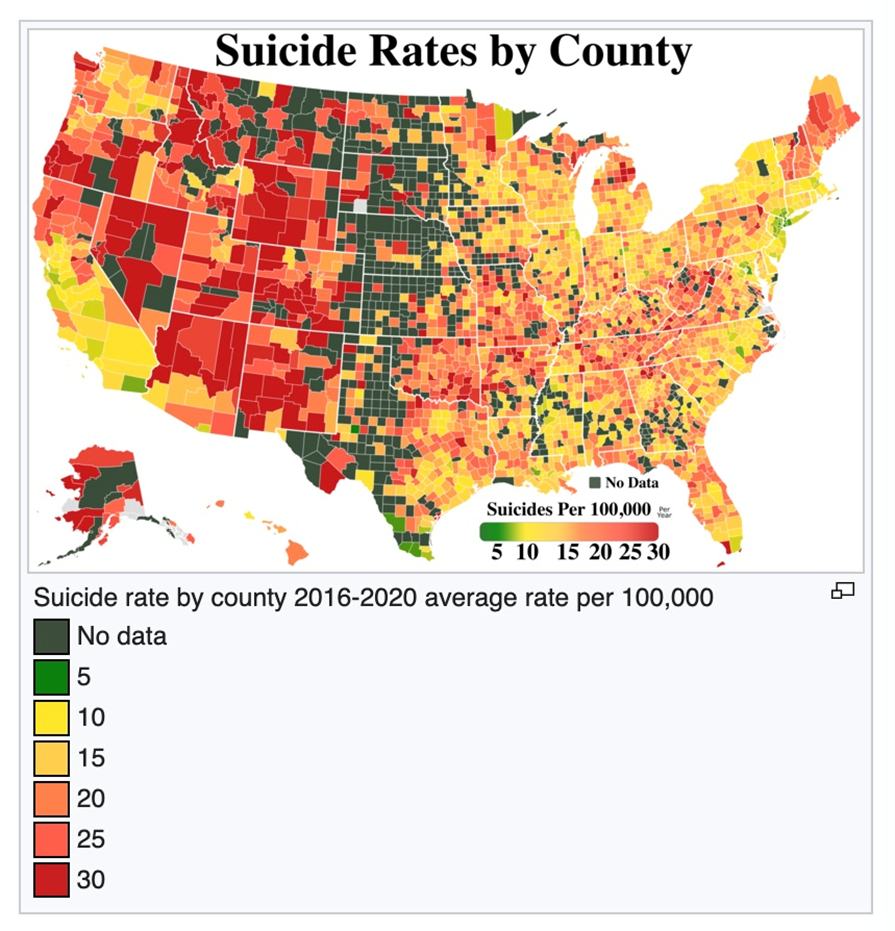

There were 44,193 suicides, a number that rose 24% between 2000 and 2015, and was the highest rate in 28 years.

Non-violent crime was also surging, with 52,404 Americans dying from drug overdoses in 2015, more than double the amount in 2002.

Updating the above statistics, we find that little has changed:

- The murder rate in 2020 was 6.5%, meaning that 6,500 of 100,000 people were murdered that year, a startling 28.6% increase from 2019;

- From 2000 to 2020, more than 800,000 people died by suicide, of which males accounted for 78%. Surging death rates from suicide, drug overdoses and alcoholism, what researchers refer to as “deaths of despair’”, are largely responsible for a consecutive three-year decline of life expectancy in the US. (Wikipedia)

- There were an estimated 107,622 drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2021, almost 15% more than 2020, when 93,655 died by taking drugs. However, the 2021 increase was half of the 30% increase in overdose deaths between 2019 and 2020.

There is a good argument that the hollowing out of the middle class, for three main reasons that we get into later in the article, has abetted the dissolution of the American family, which in turn has led to the surge in homicides, suicides and drug overdoses in the United States.

Trump often referred to the middle class during speeches about the plight of the US economy, in particular, high taxation. For example:

“I know hedge-fund guys that are making hundreds of millions of dollars a year and pay no tax. And I want to lower [tax] for the middle income. The middle class in this country has been decimated.” (The Economist)

“We’re the highest taxed nation in the world. Our middle class is just reeling from the taxes. And you know, if you think about it, the middle class and the workers of this country, who really built the country, they haven’t had a raise in 12 years. They’re making less now actually — to be even worse about it, they’re making less now than they did 12 years ago.” (Fox News)

The former president, who just announced he is running again in 2024, had a point. The middle class has been decimated, and while many commentators like to trot out figures indicating the middle class is worse off than before, few that I am aware of have researched why this is happening. That is the subject of this article.

As the rich get richer…

First we need to define what we mean by the middle class and next we get into some of the numbers showing what’s happened to it.

The Pew Research Center defines the middle class as households that earn between two-thirds and double the median US household income, which was $65,000 in 2021, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Using Pew’s yardstick, middle income is made up of people who make between $43,350 and $130,000. (Investopedia)

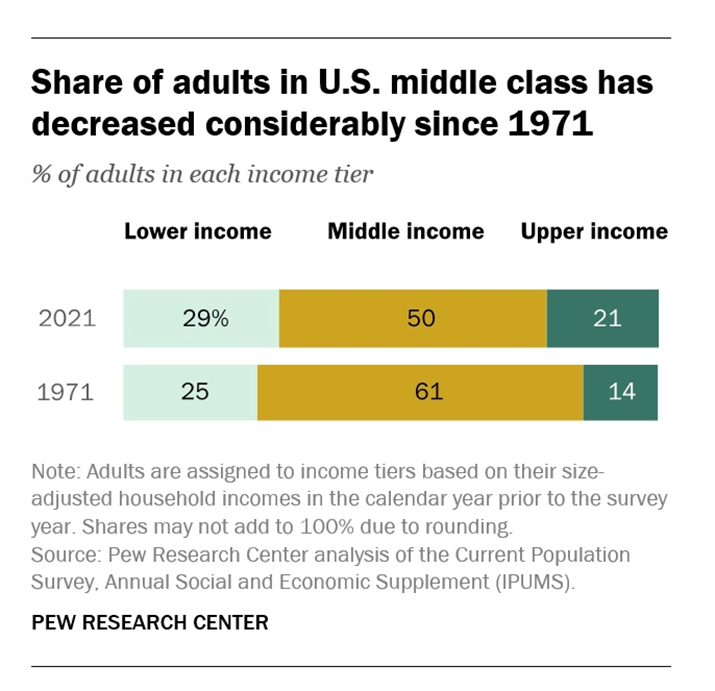

According to Pew’s latest 2021 report, 50% of American adults lived in middle-income households, down from 54% in 2001, 59% in 1981, and 61% in 1973. These stats are alarming because the middle class has historically been the engine of American economic growth and prosperity, yet over the past five decades it has shrunk.

The middle class has been decreasing both in terms of its share of the population, and its slice of the total income pie.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the Pew report was its finding that the middle class is shrinking not only because more people are poor, but because more people are rich.

Since 1971, the percentage of lowest-income earners has grown four percentage points, from 25% to 29% of the population. Over that same period, the percentage of Americans in the highest-income households rose seven percentage points, from 14% to 21% of the population.

According to Pew, the median income for lower-income households grew slower than that of middle-class households, increasing from $20,604 in 1970 to $29,963 in 2020, or 45%. The rise in income from 1970 to 2020 was steepest for upper-income households. Their median income increased 69% during that time span, from $130,008 to $219,572. In 2020, the median income of upper-income households was 7.3 times that of lower-income households, up from 6.3x in 1970. The median income of upper-income households was 2.4x that of middle-income households in 2020, up from 2.2x in 1970.

Taking just the last decade, the data shows that from 2010 to 2020, the median income of the upper class increased 9%, while the median income of the middle and lower classes climbed by only 6%.

Investopedia observes that, If we take a longer view — say, from 2000 to 2021 — we see that only the income of the upper class has recovered from the previous two economic recessions. Upper-class incomes were the only ones to rise over those twenty years.

This segmented rise has contributed to an ongoing trend since the 1970s of the divergence of the upper class from the middle and lower classes. In another piece, Pew reported that the wealth gaps between upper-income families and middle- and lower-income families were at the highest levels ever recorded.

Growing inequality is not only happening in the United States. A new Credit Suisse report finds nearly half of global household wealth (47%) is in the hands of just 1.2% of the world’s population. The infographic below shows these 62.5 million individuals control a staggering $221.7 trillion.

At the bottom of the pyramid, 2.8 billion people share a combined wealth of $5 trillion, an amount representing only 1.1% of the global wealth total.

How’s that for the rich getting richer?

Also consider: the average US household is indebted to the tune of $150,000, and each person owes $99,000.

Liabilities for the bottom 90% of households jumped $300 billion over the past year, Bloomberg reported, which is the largest annual gain on record. Consumer debt including credit cards rose to an all-time high.

In contrast, debt levels for the top 10% were virtually unchanged.

What went wrong?

Globalization

Much of the blame for the diminishment of the middle class can be placed on globalization.

Modern-day globalization is the inter-dependence of national economies through cross-border movement of goods, services, technology, capital and workers. Examples of such trade blocs are the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the European Union which is underpinned by a common currency. Concrete manifestations of globalization include the development of international standards, containerization which made the transport of ocean-going freight easier and cost-effective, and the outsourcing of services like call centers in India and the Philippines.

But globalization has not resulted in its promised rewards. Income equality in the UK and the US particularly has never been higher, companies have left their home countries to set up factories where labor is cheaper, and the ideal of the free movement of labor leading to economic growth has been lost amongst the wave of migrants turning up on European shores and the American land border, hoping for better lives but also competing with locals for scarce jobs and dependent, at least initially, on government handouts.

Trump and other populists finally said enough of globalization, it’s time to go back to the original idea of the nation-state, where local workers and industries are protected, and the rest of the world is walled off.

Anti-globalization shifts in the Trump presidency included the imposition of travel restrictions on certain Muslim states; withdrawing from the Paris Agreement on climate change; backing out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership; re-negotiating NAFTA; and tariffs on imported steel and aluminum.

International trade brings with it great benefits to American (and Canadian) consumers. It enables them to buy a wide variety of imported goods at low prices.

Globalization also allows US companies to sell more goods to people in other countries, whose incomes are boosted by overseas companies getting access to the US economy, the largest in the world. They have more money to spend buying things from Americans.

But there are two problems with globalization. The first is that American workers lose jobs, and the second is that competition for low/ medium-skilled holds down wages.

University of Georgia economics professor Jeffrey Dorman explains this rather well in a Forbes column:

The first downside of international trade that even proponents of freer trade must acknowledge is that while the country as a whole gains some people do lose. Those are people who lose their job to cheaper imports. In many cases it takes these displaced workers time to find a new job and those new jobs may pay less than their old job. These adjustment costs of trade are smaller than the gains consumers get from lower prices, but the pain is not equally shared, so some people are left worse off.

The second negative side of globalization and trade is that the pool of low- and medium-skilled workers is effectively increased when big firms can get their goods manufactured anywhere in the world. When the supply of a type of labor suddenly increases, wages for that class of labor fall. International trade essentially brings workers around the world into the same labor market as American workers.Given that many of these workers find wages of a few dollars a day (or a few dollars per hour) to be good wages, it is easy to see why some jobs move overseas…

[I]f American workers try to push their wages upward too much, those less productive workers in other countries can suddenly become a better economic deal and then the American workers lose their jobs…

American consumers and international trade have lifted millions of foreign workers out of poverty by providing a market for the goods those workers produce. That is a wonderful improvement in the world, but it has come at a cost to many American blue collar workers now forced to compete with the entire world.

Outsourcing

No better stat encapsulates the decline of the middle class than the one below, via a guest column that ran in Kitco News:

In 1970, more than a quarter of U.S. employees worked in the manufacturing sector. By 2010, only one in 10 did.

After the Second World War, the United States was the king of production. By 1945, more steel was produced in the state of Pennsylvania than in Germany and Japan combined. US manufacturing dominance continued into the Cold War era, but by the turn of the millennium, something fundamental had changed.

According to Investment Monitor, over the past 50 years, manufacturing’s share of gross domestic product in the US has shrunk from 27% to 12%. What happened?

The United States entered World War II far ahead of the competition and by the war’s end it was running circles around them. But the country grew complacent and by resting on its laurels, it lost its lead, letting Germany and Japan into the productivity race, ironically, funded by the Marshall Plan.

Their innovation systems focused on manufacturing, included Germany’s much-vaunted “Fraunhofer” model (collaboration between industry and universities) and Japan’s quality production revolution, whereas the United States was most interested in early-stage R&D (not manufacturing).

“This imbalance explains why, for many decades now, the US has been innovating new technologies that get built elsewhere, beginning with Japan in the 1970s and 1980s, and then China later on,” William Bonvillian, a lecturer at MIT and an expert in US innovation policy, was quoted saying. “More recently, we have been trying to pick up the Fraunhofer model. But guess what? China did the exact same thing.”

Investment Monitor prints the depressing stats:

Between 2000 and 2010, nearly six million jobs in US manufacturing were lost, with the sectors most prone to globalization displacement, such as textiles and furniture, taking the biggest hit.

US manufacturing output grew only 0.5% per year between 2000 and 2007, and during the financial crisis of 2007–09, fell by a huge 10.3%. Only in very recent years has manufacturing output returned to pre-recession levels. Similarly, US productivity growth in manufacturing also hit a nadir that decade, and remains at historically low levels.

It wasn’t just that US companies failed to compete; many actively sought to shed more expensive American workers during this “lost decade” of outsourcing.

Michael Pento from the Kitco column comments,

In October of 2015, Disney, the self-proclaimed happiest place on earth, didn’t make 250 of their U.S. employees very happy when they replaced them with immigrants on temporary visas. This transaction was facilitated by an outsourcing firm based in India.

And Disney is not the alone; similar “outsourcings” have happened across the country. Businesses have been misusing temporary worker permits, known as H-1B visas, to place immigrants willing to work for less money in technology jobs based in the United States.

According to The Balance, in 2019, US overseas affiliates employed 14.6 million workers, with the four industries most affected being technology, call centers, human resources and manufacturing. America has lost jobs to China, Mexico, India, and other countries with lower wage standards. Companies outsource domestically as well and have been increasing their reliance on freelancers, temp workers, and part-timers (the so-called “gig economy). Robots have also replaced some American workers.

The death of middle management

The evisceration of the middle class is not only due to the loss of manufacturing jobs to lower-wage jurisdictions/ outsourcing, hiring part-timers or getting robots to work for free.

It’s also about how the typical American company is structured and the loss of mobility that enabled employees to “work their way up the ladder.”

A 2020 feature article in The Atlantic titled ‘How McKinsey Destroyed the Middle Class’, is required reading for anybody wishing to go beyond the headlines and understand what is really happening to middle managers, many of whom have disappeared in the name of increasing efficiencies and eliminating redundancies. The following text has been edited for brevity, the identification of key concepts and flow:

In the middle of the last century, management saturated American corporations. Every worker, from the CEO down to production personnel, served partly as a manager, participating in planning and coordination along an unbroken continuum in which each job closely resembled its nearest neighbor. Elaborately layered middle managers—or “organization men” — coordinated production among long-term employees. In turn, companies taught workers the skills they needed to rise up the ranks. At IBM, for example, a 40-year worker might spend more than four years, or 10 percent, of his work life in fully paid, IBM-provided training.

Mid-century labor unions (which represented a third of the private-sector workforce), organized the lower rungs of a company’s hierarchy into an additional control center —and in this way also contributed to the management function. Even production workers became, on account of lifetime employment and workplace training, functionally the lowest-level managers.

The mid-century corporation’s workplace training and many-layered hierarchy built a pipeline through which the top jobs might be filled. The saying “from the mail room to the corner office” captured something real, and even the most menial jobs opened pathways to promotion.

Middle managers shared not just the responsibilities but also the income and status gained from running their companies. Top executives enjoyed commensurately less control and captured lower incomes. From 1939 to 1950, hourly workers’ wages rose roughly three times faster than elite executives’ pay. The management function’s wide diffusion throughout the workforce substantially built the mid-century middle class.

The earliest consultants were engineers who advised factory owners on measuring and improving efficiencies. McKinsey, which didn’t hire its first Harvard M.B.A. until 1953, retained a diffident and traditional ethos—requiring its consultants to wear fedoras until President John F. Kennedy stopped wearing his.

Things changed in the 1960s, with McKinsey leading the way. In 1965 and 1966, the firm placed help-wanted ads to establish its own eliteness, seeking to hire “not just the run-of-that-mill but, instead, scholars.”

A new ideal of shareholder primacy gave the newly ambitious management consultants a guiding purpose. During the 1970s, and accelerating into the ’80s and ’90s, the upgraded management consultants pursued this duty by expressly and relentlessly taking aim at the middle managers who had dominated mid-century firms, and whose wages weighed down the bottom line.

The downsizing peaked during the extraordinary economic boom of the 1990s. The culls, moreover, were dramatic. AT&T, for example, once aimed to cut the ratio of managers to nonmanagers in one of its units from 1:5 to 1:30. Overall, middle managers were downsized at nearly twice the rate of nonmanagerial workers.

Production workers did not escape the whirlwind, as companies — again with help from consultants — stripped them of their residual management functions and the benefits that these sustained.

Corporations broke their unions, and jobs that once carried bright futures became gloomy. United Parcel Service, long famous for its full-time workers and promoting from within, began emphasizing part-time work in 1993. Its union—the Teamsters—struck in 1997, under the slogan “Part-time America won’t work,” but failed to return the company to its past employment practices. UPS has since hired more than half a million part-time workers, with just 13,000 advancing within the company.

Overall, the share of private-sector workers belonging to a union fell from about one-third in 1960 to less than one-sixteenth in 2016. In some cases, downsized employees have been hired back as subcontractors, with no long-term claim on the companies and no role in running them. When IBM laid off masses of workers in the 1990s, for example, it hired back one in five as consultants. Other corporations were built from scratch on a subcontracting model. The clothing brand United Colors of Benetton has only 1,500 employees but uses 25,000 workers through subcontractors.

The shift from permanent to precarious jobs continues apace. And the gig economy is just a high-tech generalization of the sub-contractor model. Uber is a more extreme Benetton; it deprives drivers of any role in planning and coordination, and it has literally no corporate hierarchy through which drivers can rise up to join management. As ever, consultants are at the forefront of change, aiming to disrupt the management function. A new breed of management-consulting firms now deploys algorithmic processing to automate not the line workers’ or sales associates’ jobs, but the manager’s job.

In effect, management consulting is a tool that allows corporations to replace lifetime employees with short-term, part-time, and even subcontracted workers, hired under ever more tightly controlled arrangements, who sell particular skills and even specified outputs, and who manage nothing at all.

The management function has not been rendered unnecessary, of course, or disappeared. Instead, the managerial control stripped from middle managers and production workers has been concentrated in a narrow cadre of executives who monopolize planning and coordination. Mid-century, democratic management empowered ordinary workers and disempowered elite executives, so that a bad CEO could do little to harm a company and a good one little to help it. Today, top executives boast immense powers of command—and, as a result, capture virtually all of management’s economic returns. Whereas at mid-century a typical large-company CEO made 20 times a production worker’s income, today’s CEOs make nearly 300 times as much. In a recent year, the five highest-paid employees of the S&P 1500 (7,500 elite executives overall), obtained income equal to about 10 percent of the total profits of the entire S&P 1500.

Management consultants insist that meritocracy required the restructuring that they encouraged—that, as Kiechel put it dryly, “we are not all in this together; some pigs are smarter than other pigs and deserve more money.” Consultants seek, in this way, to legitimate both the job cuts and the explosion of elite pay. Properly understood, the corporate reorganizations were, then, not merely technocratic but ideological. Rather than simply improving management, to make American corporations lean and fit, they fostered hierarchy, making management, in David Gordon’s memorable phrase, “fat and mean.”

Whereas a century ago, fewer than one in five of America’s business leaders had completed college, top executives today typically have elite degrees—M.B.A.s as well as bachelor’s degrees—and deep ties to management consulting. Indeed, a greater share of McKinsey employees become CEOs than any other company’s in the world.

Today, management consulting sits beside finance as the most popular first job for graduates of Harvard, Princeton, and Yale.

Making ends meet, barely

Once upon a time, being middle class meant having a steady income, home ownership, and security for the future. Most people had the ability to save (for their children’s education and for retirement), and to acquire assets, such as a recreational vehicle or a summer cottage.

Now, it mostly means the ability to pay your bills and to service debt.

While in 2019, 95% of people in households making over a hundred grand a year reported they were doing ok financially, it’s becoming more expensive to be middle class. Wages for all but the wealthy have remained stagnant for the past four decades. Those that are getting raises are just keeping pace with inflation, not the actual cost of living.

Vox reports that, Basic costs are taking up bigger chunks of the monthly middle-class paycheck. In 2019, the middle class was spending about $4,900 a year on out-of-pocket health care costs. More middle- and high-income people than ever are renting, and 27 percent are considered “cost burdened,” paying more than 30 percent of their income on rent, particularly in expensive metro areas. Then there’s the truly astronomical price of child care. In Washington state, for example, which ranks ninth in the US for child care costs, care for an infant and a 4-year-old averages $25,605 a year, or 35.5 percent of the median family income.

Meanwhile, the level of indebtedness is rising and the savings rate, with the exception of the pandemic period, has steadily declined.

In 1960, the savings rate was 11%. By 1990 it was 8.8%, in 2000 it had fallen to 4.2%, and by 2007 the rate was 3.6%. The Bureau of Economic Analysis puts the current savings rate, as of September, 2022, at 3.1%.

In March 2020, US household debt hit $14.3 trillion, the highest since the financial crisis. A new study quoted by Global News found Canadians are leaning more heavily on credit cards, amid higher inflation and despite rising interest on credit cards. Equifax Canada’s survey found the average credit card held by Canadians as of Sept. 30 was at a record-high $2,121. US credit card debt just hit an all-time high of $930 billion.

Anticipating the question, “Why don’t middle-class people just curb their spending,” the Vox article points to the difficulty of families (or single people) significantly shifting their consumption patterns. There’s also the social stigma, especially in the United States which places a high value on having money to spend, that comes with rescinding that status, particularly for those who have grown up poor.

Conclusion

By practically every metric, the middle class is being hollowed out; the richer really are getting richer and the poor are becoming poorer.

Perhaps this partially explains the current state of political polarization in the United States and Canada. Middle class people can only improve their economic situation so much; their opportunities to “move up the ladder” are limited and they are finding the cost of living prohibitively expensive, especially right now with rising inflation and interest rates. Many have got to the point where they’re living on their credit cards, in effect borrowing to keep spending, going ever deeper into debt.

They no longer trust politicians to be an agent for economic redistribution, say through tax cuts or subsidies, and are therefore looking for strong leadership, on the left or the right, to help them get ahead.

For anyone who still doesn’t believe the middle class is being systematically destroyed, I suggest you watch this 12-minute video.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.