The DRC just turned the screws on cobalt supply

2020.02.12

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is finally doing something about cobalt mining, a sector whose reputation has been sullied by illegality, child labor, accusations of modern-day slavery, and lax safety standards.

Recently the Congo government created a new company, Enterprise Generale du Cobalt (EGC), that will have a monopoly on buying and marketing cobalt from “artisanal miners”, usually impoverished workers who dig for minerals, including cobalt and gold, without mechanized equipment.

But while the state-owned firm may provide an air of respectability to the African country, which has been shamed by human rights groups, and to Big Tech buyers of cobalt like Apple and Tesla accused of enabling “blood cobalt”, it will also put more pressure on the already strained supply of the critical metal.

Targeted

Allegations of human rights abuses including child labor have put the DRC in the wrong kind of international spotlight. BMW, Daimler (owner of Mercedes), Volkswagen and Apple are among big-name companies that source raw materials from the DRC, and facing pressure to make their supply chains transparent.

In fact a number of US tech companies have been accused of benefiting from cobalt extracted by child-miners in the DRC. In December Cnet reported that International Rights Advocates, a non-profit, filed a lawsuit in a Washington court on behalf of 14 plaintiffs – guardians of children either killed or seriously injured in tunnel or wall collapses. The defendants in the suit, writes Cnet, are Apple, Microsoft, Dell, Tesla and Alphabet, Google’s parent company.

It is probable the DRC government was pressured to clean up its cobalt supply chain by these companies, who need cobalt for its use in electronics. Elected officials will also want to avoid bans from the London Metal Exchange. The world’s biggest market for industrial metals plans to reject metal tainted by human rights abuses.

Cobalt in batteries

Until recently cobalt usage was dominated by metal alloys, due to the metal’s resistance to high temperatures, strong magnetism and wear/corrosion resistance. These characteristics make cobalt a perfect fit for aerospace superalloys, cutting tools, binders for cemented carbides, permanent magnets and semi-conductors.

Over the last 20 years however, the market for cobalt has shifted to chemicals, particularly compounds needed for rechargeable batteries, which represent 78% of chemical cobalt demand. Other cobalt chemicals are used in catalysts to refine petroleum, and to make plastics, steel-belted radial tires, dryers, pigments, food additives and agricultural products.

Cobalt is the common denominator between the two main types of electric vehicle batteries, nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) and nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM).

A lithium-ion battery for EVs has to be both strong and long-lasting, through many charging cycles. It’s mostly the nickel that gives the battery its strength, and the cobalt that gives it stability and resilience, to ensure an industry-standard 8-year lifespan.

Cobalt is actually the “safe” element in the battery cathode. Reducing the amount of cobalt shortens the life of the battery cell, and makes it vulnerable to over-heating. There’s a reason security agents at the airport ask you if you have any lithium-ion batteries in your checked baggage!

So, while Elon Musk claims Tesla can reduce the amount of cobalt in its Tesla 3 batteries to zero, to cut costs (cobalt is much more expensive that nickel or aluminum), the reality is that cobalt is an indispensable battery ingredient. There will always be some amount of cobalt in an EV battery.

The swing producer

Shifting power from the artisanal miners to a state-run monopoly fulfills a couple of goals for the DRC, which accounts for nearly two-thirds of world cobalt supply. Not only does it potentially remove the stain of illegality from the mining industry, and by proxy, the government, putting EGC in charge will also boost tax revenue (illegally mined cobalt goes under the radar) and will leverage Congo to exert more control over the cobalt price.

To understand the latter, we need to know how artisanal mining has played the role of “swing producer” in the global cobalt market, and how that is likely to change.

When cobalt prices are high – like during 2018’s EV-fueled price rally – there’s good money in cobalt mining, for an illegal miner, despite its reputation for being dangerous and potentially lethal due to tunnel or wall collapses. During cobalt price booms, artisanal miners flood to the mining pits in droves, up to 2,000 per day, all aiming to capitalize on high prices.

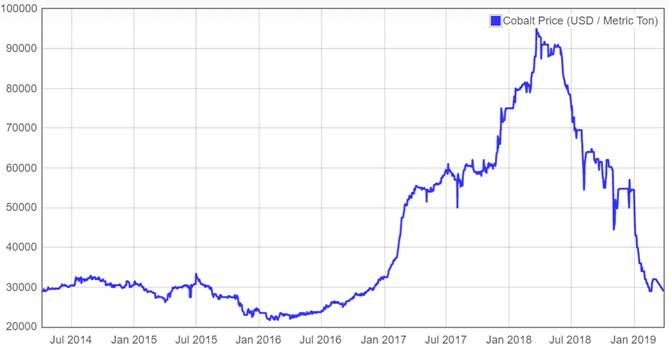

Artisanal production surged from around 6,000 tonnes in 2016 to over 19,000t in 2017 as cobalt rose from about $20,000 to $95,000 per tonne, according to research firm CRU.

It’s estimated the illegal sector represents 20% of DRC cobalt supply – enough to move the market. That 20% during boom times has the effect of lowering the price through oversupply, an example of “high prices are the cure for high prices”.

When cobalt prices are down, as they are currently due to overzealous production during the 2016-18 boom, the artisanals head to the gold fields where they can make a decent day’s pay, with gold north of $1,550/oz.

Cobalt price per tonne

But having the artisanals as swing producer isn’t good for the DRC government. Not only do they deprive the government of needed tax revenue, their production destabilizes the price – making it swing wildly from one extreme to the other. Having a new monopoly in charge of collecting artisanals’ output, and just one company, state-run Gecamines, mine cobalt and metals like copper and zinc, is expected to calm the volatility in cobalt prices, bolster demand from end users, and allow the government to maximize cobalt revenue.

At least that’s the theory; if EGC is able to control artisanal production, it will assume the mantle of swing producer.

Here’s how it would work in practice: EGC buys cobalt from cooperatives, which pool the cobalt mined by individual workers. EGC then squirrels away the cobalt in storage, meaning it is effectively taken off the market. Good for the price, right?

And much better for supply chain transparency. Currently, production from artisanal miners is bought by (mostly Chinese) middlemen who sell it to processors in China – which imports 98% of its cobalt from the DRC and produces around half of the world’s refined cobalt.

Artisanal product becomes mixed with official-sector product, causing traceability problems for end-users desperate to avoid being tainted by allegations of using a metal generated by child or “slave” labour.

The EGC will use its purchasing power to extend official oversight on working conditions in the artisanal sector, using non-government organizations to select cooperatives based on their compliance with responsible sourcing criteria.

Those that don’t qualify will be “sanctioned,” according to [Albert Yuma, chairman of state mining company Gecamines, which will oversee the EGC].That may be a euphemism for being closed.

One of the losers in this new arrangement is China. No longer will Chinese traders have power over DRC’s hard-scrabble rock diggers. Presumably these individuals will be forced out, replaced by cooperatives that meet the criteria for ethical cobalt mining, meaning that only cobalt produced by Chinese companies, or DRC mines with Chinese ownership, would be shipped to China for processing.

China controls about 85% of global cobalt supply, including an offtake agreement with Glencore, the largest producer of the mineral, to sell cobalt hydroxide to Chinese chemicals firm GEM. China Molybdenum is the largest shareholder in the major DRC copper-cobalt mine Tenke Fungurume, which supplies cobalt to the Kokkola refinery in Finland.

Locking up supply

The current cobalt price of around $35,000 a tonne shows the continuing supply overhang but it doesn’t reflect the other trend that is happening right now in the cobalt market – offtake agreements.

This week global miner and commodities trader Glencore announced a five-year supply agreement with Korean battery maker Samsung SDI. Under the deal, Switzerland-based Glencore will ship up to 21,000 tonnes of cobalt – which accounts for 45% of its 2019 production of 46,300 tonnes.

The cobalt will be mined from the company’s Katanga mine in the DRC.

The Glencore-Samsung offtake agreement follows four cobalt offtakes signed last year by Glencore – with BMW from its Murrin mine in Australia, Korea’s SK Innovation for 30,000 tonnes, Belgian chemicals firm Unicore, and battery recycler GEM, from China.

Tesla is also reportedly talking to Glencore about buying cobalt for its gigafactory in Shanghai.

Taking stock of all these offtake agreements, reveals a startling fact: the cobalt market is now pretty much locked up, between Glencore and China.

According to Benchmark Intelligence, an industry supply and price tracker, not including a potential deal with Tesla, more than 80% of Glencore’s DRC cobalt hydroxide production is now cemented in long-term agreements.

So, if 80% of cobalt produced by Glencore – the largest cobalt mining company in the world – is spoken for, and most of Glencore’s cobalt come from the DRC, which has two-thirds of global production, that doesn’t leave a lot for newcomers.

Remember China is heavily invested in the DRC and buys nearly 100% of its cobalt from there. China Molybdenum is the world’s second largest cobalt producer and it owns the majority of the Tenke Fungurume mine in the DRC. China has a lock on the world’s refined cobalt – which includes the 20% of DRC production that is handled by Chinese middlemen who buy the cobalt and sell it to Chinese refiners.

That 20% will henceforth be collected by the new monopoly, EGC, so it is considered accounted for – unavailable to the market. It will either be stockpiled or sold to China, which refines the cobalt in-country and sells it mostly to battery component manufacturers in China or South Korea.

Do you see where this is going? If you’re an EV manufacturer in the United States or Canada, without a cobalt source for your batteries, where are you going to go? Even if you do find a supplier, cobalt will almost certainly be more expensive. A DRC monopoly that wants to see higher prices has just replaced artisanal miners as the swing producer. The days of cobalt price turbulence may be over. With demand for EVs continuing to grow exponentially each year (plus all the cobalt needed for smart phones, other electronics, and metal alloys) and the small, already tight cobalt market getting tighter, we believe prices have nowhere to go but up.

China and Indonesian nickel

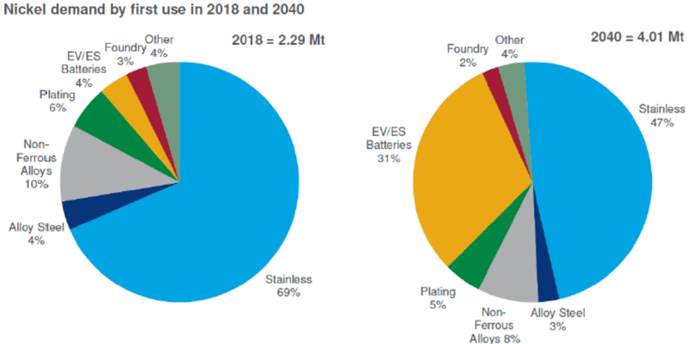

As it has done with cobalt, graphite and rare earths, China appears to be cornering the battery nickel market.

Reuters reported on a $4 billion Chinese-led project to produce battery-grade nickel chemicals, that Indonesia hopes will attract electric-vehicle makers into the country.

Construction started last year, led by a consortium of Chinese developers including the world’s largest stainless steel maker, Tsingshan Holding Group, battery company GEM Co Ltd., and units of CATL – the largest EV battery company in the world. Nickel feedstock for the plant would come from Indonesia’s nickel laterite ores (Tsingshan says the feed would be abandoned low-grade nickel ores)

The nation of islands wants to become a global hub for processing raw nickel into battery-grade nickel sulfate, and for producing/ exporting EVs to Asia and possibly Australia. Indonesia is the largest nickel producer by far, last year outputting 800,000 tonnes compared to 420,000 from its closest rival, the Philippines.

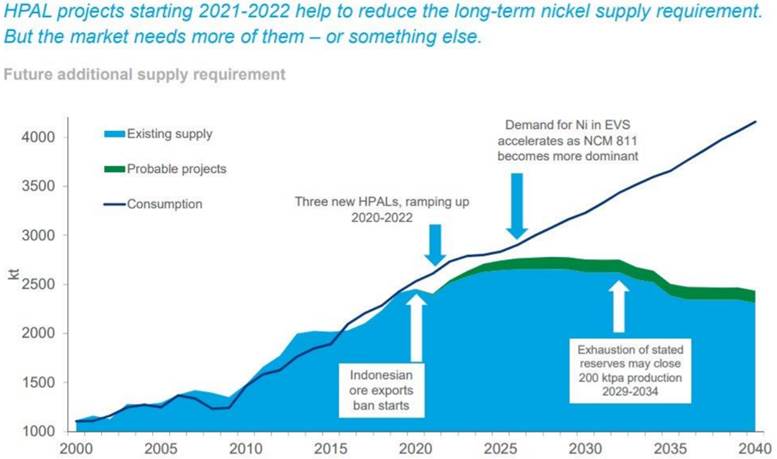

Tsingshan plans to construct an Indonesian plant to produce nickel-cobalt salts from nickel laterite ores. Using HPAL technology (see below) Tsingshan says it will transform Class 2 nickel laterite deposits into Class 1 metal for the battery market.

Most of the world’s nickel production, about 70%, is used as an alloying agent in stainless steel. In 2007 when nickel prices ran past $50,000 a tonne, top stainless consumer China balked. Beijing discovered an alternative to pure nickel in the making of stainless steel, called nickel pig iron (NPI). The emergence of NPI revolutionized the nickel industry. The bulk of production shifted from the northern latitudes that host nickel sulfide deposits, to huge nickel laterite belts found around the equator – mostly in the Philippines and Indonesia.

Class 2 nickel is primarily used to make stainless steel, which accounts for two-thirds of global nickel demand. Sulfide deposits provide ore for Class 1 nickel users which includes battery manufacturers. These battery-cos purchase nickel sulfate, derived from high-grade nickel sulfide deposits.

The main benefit of sulfide ores is that they can be concentrated using simple flotation, meaning processing costs are much lower than nickel laterite deposits – such as those in Indonesia and the Philippines.

However, large-scale sulfide deposits are extremely rare. Existing sulfide mines are becoming depleted, with precious few to replace them. It’s important to note that less than half of the world’s nickel is suitable for the biggest growth market – EV batteries.

According to BloombergNEF, demand for Class 1 nickel is expected to out-run supply within five years, fueled by rising consumption by EV battery suppliers.

The solution seems simple: just mine the laterites to produce nickel sulfate for batteries.

Problem is, there is no simple separation technique for nickel laterites – despite the plant the Chinese are building in Indonesia to do just that. Laterite projects have high capital costs and therefore require large economies of scale to be viable.

The mineralogy is complicated and the processing technology is expensive and not particularly reliable.

Laterite saprolite (higher nickel, magnesium and silica but lower iron content) orebodies are processed with standard pyrometallurgical technology.

A laterite limonite zone that is higher in iron and lower in nickel, magnesium and silica, requires High Pressure Acid Leaching (HPAL) technology to extract the nickel; the Caron Process is no longer considered viable.

HPAL – whose performance record has been highly mixed – involves processing ore in a sulfuric acid leach at temperatures up to 270ºC and pressures up to 600 psi to extract the nickel and cobalt from the iron-rich ore; the pressure leaching is done in titanium-lined autoclaves.

Counter-current decantation is used to separate the solids and liquids. Separating and purifying the nickel/cobalt solution is done by solvent extraction and electrowinning.

The advantage of HPAL is its ability to process low-grade nickel laterite ores, to recover nickel and cobalt. However, HPAL is unable to process high-magnesium or saprolite ores, it has high maintenance costs due to the sulfuric acid (average 260-400 kg/t at existing operations), and it comes with the cost, environmental impact and hassle of disposing the magnesium sulfate effluent waste.

Despite the difficulties with HPAL, China is working with Indonesia to develop a huge facility for developing battery-grade nickel Chinese-led, of course. China doesn’t really care about helping Indonesia to become an EV battery hub. Its real goal is to establish a nickel-processing beachhead in the largest nickel producer in the world, using Chinese technology to process Class 2 nickel laterite deposits into Class 1 battery-grade metal.

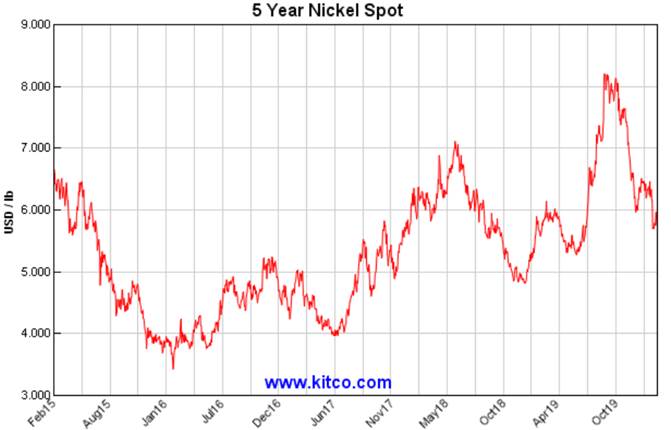

The key point it this: In building all these new nickel processing plants in Indonesia, locking up laterite nickel supply to make nickel sulfate suitable for EV batteries, using the more expensive HPAL, China is setting the stage for a dramatic increase in the price of nickel chemicals. And that means raw nickel prices will have to go up too, because mining companies will no longer be able to profitably mine and process nickel at the current $6 a pound – prices will need to rise, for them to afford the much higher costs of processing laterite nickel deposits into battery-grade nickel – let alone dealing with the greater complexity and waste disposal issues accompanying HPAL.

Inomin Mines (TSX-V:MINE)

Given that China and Glencore have locked up most of the world’s cobalt via offtakes with the DRC, and China seems hell bent on squeezing battery-grade nickel from laterite deposits in Indonesia using costly HPAL, wouldn’t it make sense to look for a nickel sulfide deposit, maybe one with a low-grade cobalt kicker?

Inomin Mines (TSX-V:MINE ) thinks so. The junior exploration company is focused on nickel and cobalt in British Columbia.

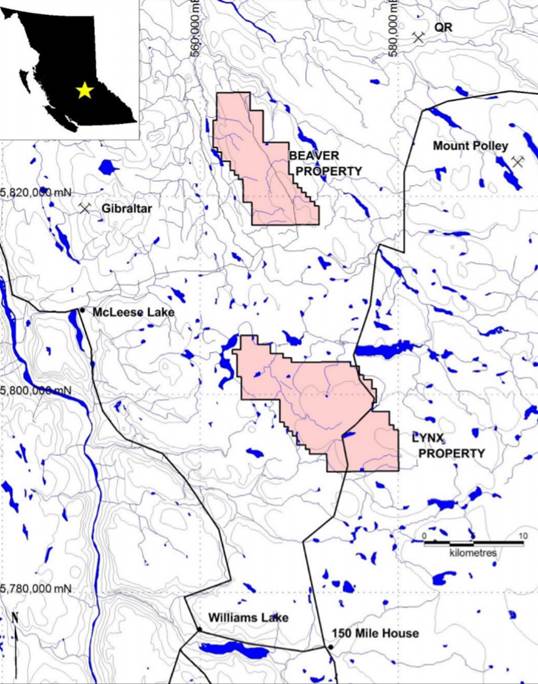

The company’s 7,528 hectare Beaver and 12,662 hectare Lynx properties are located between two major BC mines overlying world-class porphyry deposits – Taseko’s Gibraltar mine and Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley. Gibraltar is the second largest open-pit copper mine in Canada.

Mining “close-ology” dictates the importance of developing a mine that is nearby, or located within similar geology, to an existing producer(s). Even better if that producer is mining a porphyry. Porphyry deposits are usually low-grade but large and bulk-mineable, making them attractive targets for mineral explorers.

Highlights from a 2014 drill program at Beaver included 157.3 meters, 106.6m, and 86m, all containing 0.18% nickel and 0.01% cobalt. These uniform assays are low grade, but don’t let that dissuade you.

A little back-of-the envelope math by yours truly shows the potential for an impressive nickel-cobalt deposit of significant scale to interest a major mining company or funding partner. For the details, read Inomin eyeing monster BC nickel sulphide deposits

It’s important to mention that the metallurgy at Beaver has already been tested, though not proven. A pre-scoping metallurgical study in 2015 demonstrated that 90% of the nickel is within nickel sulfide minerals, heazlewoodite and pentlandite. In other words, 91% of the nickel should be recoverable. Initial testing revealed good recoveries from conventional flotation methods, or possibly lower-cost heap leaching.

In November Inomin announced the expansion of the nickel project by 6,040 hectares, through the purchase of eight claims. That puts the Beaver nickel-cobalt property at 7,258 ha, and Lynx at 12,662 ha, for a combined 20,000 ha.

Inomin has a Class 1 nickel project in a Tier 1 jurisdiction. BC was in the top quarter of all countries surveyed in the Fraser Institute’s latest investment attractiveness rankings.

In fact Inomin’s Beaver and Lynx properties have all five elements a nickel junior must have to interest a major: size, grade, scalability, longevity and infrastructure. The company already has an advanced nickel system at Beaver, proven by drilling, and a similar but potentially much larger nickel opportunity at Lynx.

Combine all of these pluses with the fact that nickel and cobalt are both facing supply restrictions, therefore, higher prices for the foreseeable future, and you might start thinking there are Class 1 nickel projects in much better and safer mining jurisdictions, like Inomin’s nickel/ cobalt project in BC, that could, potentially, feed the battery and car-makers of the future.

Inomin Mines

TSX.V:MINE

Cdn$0.045, 2020.2.11

Shares Outstanding 16,584,264m

Market cap Cdn$746,291.00

MINE website

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Richard does not own shares of Inomin Mines (TSX.V:MINE), MINE is an advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.