The decline of the Russian navy – Richard Mills

2023.07.06

The recently attempted coup by Yevgeny Prigozhin, head of Russia’s mercenary Wagner Group, was anticlimactic.

A day after Prigozhin and his powerful military force seized a key military base in southern Russia, and the city of Rostov-on-Don, the rebellion was suddenly called off before reaching the capital, Moscow.

What happened next was even more surprising. Rather than punish the rebels, President Vladimir Putin magnanimously allowed Prigozhin and his commanders to retreat to Belarus.

While The Guardian claimed that Vladimir Putin’s reaction was a show of strength, CNBC opined The fact that the outspoken Prigozhin could even mount an armed mutiny with his private military company, the Wagner Group, with little resistance and an apparently muted response is widely seen as a deep political blow for Putin and his regime.

The US media outlet said Russia experts and analysts characterized the “24 hours that shook the Kremlin” as the biggest challenge to Putin and the Russian elite in decades.

How could this happen under his watch? The autocrat known for being unforgiving in his dealings with opponents and critics? For months, Prigozhin had been in an increasingly heated dispute with the country’s military leadership, accusing them of treachery and mismanaging the invasion of Ukraine.

The former hatchet man for Putin accused Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and army commander Valery Gerasimov of turning their backs on his mercenary force (like not sending enough ammunition), that has played a key role in Donetsk, eastern Ukraine, for months. Tensions came to a head when the Defense Ministry announced that all private military groups including Wagner would have to sign contracts. Prigozhin refused.

Arguably, the failure of Putin to declare a swift victory in Ukraine, as the conflict drags into its 18th month, not only speaks to cracks in his leadership, as demonstrated by the Prigozhin incident, but in the Russian military, especially its increasingly depleted navy.

A brief naval history

In the 1920s, the Red Army planned to use its substantial forces to attack potential threats beyond the Soviet Union’s western border, while the navy’s job was to defend the coasts. In pursuit of the latter, Josef Stalin implemented an aggressive ship-building program. In the late 1930s, the Soviet navy started strengthening its forces in the Baltic and the Black seas and on the Pacific and Arctic coasts. The plans however were upended by the Second World War, which took the fight to Germany and diverted resources to the army.

Political support for the Soviet navy improved following the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, which demonstrated the utility of sea power. Soviet leaders were reportedly receptive to Fleet Admiral Sergey Georgyevich Gorshkov’s arguments for an expanded and wide-ranging battle fleet — despite then-leader Nikita Khrushchev’s focus on advancements in nuclear missiles and bias towards submarines over surface ships.

According to the U.S. Naval Institute, the Russian navy’s history yields two observations: that the navy has always been subordinate to continental security concerns; and that long periods of neglect have often forced the navy to make up for lost time.

Lessons from the Ukraine war

Ever since Catherine the Great bolted the Crimean peninsula onto Russia in 1783, the Black Sea fleet’s home port has been Sevastapol. Although Ukraine allowed Russia to keep operating its bases there after the 1991 breakup of the Soviet Union (and the independence of Ukraine), in 2014 Russia re-annexed the peninsula anyway. The recapture of Crimea is now a Ukrainian war goal.

While the Russian navy has successfully blockaded ports and launched missiles against targets across Ukraine, it also lost its flagship Black Sea fleet vessel ‘Moska’ to Ukrainian anti-ship missiles, failed to ensure Russian control of strategically important Snake Island, and did not implement decisive amphibious operations along Ukraine’s littoral areas (The Moscow Times, June 30, 2022; The Insider, Oct. 20, 2022).

The U.S. Naval Institute says the Russian navy’s performance in the war offers three lessons: first, that the historical cycle is repeating, with the surface fleet’s utility and combat power still surprisingly limited despite state investments in shipbuilding and weapons development; second, that Russia’s current military strategy assigns roles for the navy that still serve a land-based, active-defense strategy; and third, that the Russian navy still faces significant challenges meeting its strategic requirements, despite improvements in quantity and quality of cruise missiles and the commissioning of new ships.

Strategic shift

The most obvious strategic challenge for Russia is how to deal with the Baltic region that, until very recently, it had a free hand in, but is now almost completely hemmed in by NATO countries.

Indeed it is deliciously ironic that Putin claims to have launched his war with Ukraine to keep NATO away from Russia’s borders, yet instead, the conflict triggered a new expansion of the defensive alliance. The accession of Finland in April added more than 1,300 km to the NATO-Russia border, followed by the entry of Sweden, which effectively turns the Baltic Sea into NATO’s backyard.

The two Nordic countries had for decades remained outside of NATO, but were persuaded to join following Putin’s attack on Ukraine. Both maintain highly professional navies and air forces.

Both the Baltic and the Black Sea share an important geographical feature: they each have a narrow opening into oceans. It’s effectively one way in, one way out. Ships that want to exit the Black Sea to enter the Mediterranean, for example, have to sail the Bosphorous River and the Dardanelles Strait, both of which are within the territorial waters of Turkey, a NATO member. After Russia invaded Ukraine, Turkey closed the strait to all warships, a move that mostly affects Russia.

For reasons of limited access, therefore, Russia prefers to keep its blue-water navy and its nuclear submarines at its Arctic and Pacific ports.

A commentator told CBC News that NATO’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine threatens its Baltic and Black Sea fleets, which were central to Russia’s emergence as a great power after the 1790s.

“If this was viewed as a gamble on the part of Mr. Putin to recreate this image he has of Russia, this historic image of Russian being a great power, it’s being thwarted diplomatically in the Baltic and militarily in Ukraine and the Black Sea,” said Tanya Grodzinski, a naval historian at the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario.

The Black Sea coast is mostly controlled by Turkey, which is becoming a rising naval power, and despite initially seeking closer ties to Russia following the Ukraine invasion, is now distancing itself from Moscow.

Some say Turkey’s change of heart has to do with a secret agreement with NATO, such as assurances on its eventual EU membership, or its desire to purchase F-16 jets from the United States, in exchange for agreeing to Finland and Sweden’s accession.

The US previously canceled the jet sales to Turkey, following the purchase by the Erdogan government of a Russian S-400 air-defense system, which cast doubt on Turkey’s loyalty to NATO.

Yet despite serving as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine, in the recently suspended agreement to permit Ukrainian grain shipments across the Black Sea, Turkey has pivoted away from Russia and towards the European Union, which it needs more than Moscow.

(The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace writes that, due to a severe economic crisis, Turkey is in dire need of foreign capital, the source of which continues to be Western countries, primarily the Netherlands, the US and the UK, which together account for about 30%. Russia, in contrast, only represents about 3.7% of Turkey’s exports. Even more painful for Moscow, says Carnegie, was Turkey’s decision to transfer five captured Ukraine commanders back to Ukraine, backtracking on previous assurances they would not be returned from Turkey until the end of the war.)

Putin, meanwhile, has seemingly done little to prevent the rapprochement between Turkey and the West.

According to a recent article by Project Syndicate, Erdogan not only withdrew his veto of Sweden’s NATO accession in exchange for the sale of American fighter jets, he joined the rest of the alliance in voicing support for Ukraine’s membership:

With these moves, Erdoğan has fully rejoined the Western convoy, much to the Kremlin’s dismay. Turkey has since even sought to calm its highly charged relations with Greece. Rather than ratcheting up tensions with its neighbor (and NATO member) in the Aegean and the eastern Mediterranean, it is now pursuing rapprochement and cooperation.

Also, Project Syndicate author Joschka Fischer believes that a weakened Russia is limited in its influence over Turkey, stating that:

By shifting toward Kyiv, the Turkish president is essentially testing Moscow’s new red lines. How strongly is Russia willing to react in a situation when it is simultaneously fending off a Ukrainian counteroffensive and recovering from the uprising by the Wagner mercenaries?

(Remember, Turkey controls Russia’s access to the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean by way of the Bosphorus.)

The other major threat to Russia’s Black Sea fleet is Ukraine. Ukraine’s acquisition of British Storm Shadow and French SCALP missiles brings the entire Crimean peninsula within range of Ukrainian weapons, CBC said, making Sevastapol, once a safe port, fundamentally unsafe for Russian warships.

As for the Baltic fleet, the Center for Global Affairs & Strategic Studies (GASS) notes that Now, all nations with coasts in it except for Russia´s tiny Western coast and Kaliningrad—that is, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Germany — are NATO nations…

Should they launch any hostile action in the area, the allied block would dispose of a bigger force capacity and an enhanced operational cooperation, which would mitigate the negative consequences.

Estonian Lieutenant General Martin Herem recently stated this very clearly: “[Sweden and Finland´s accession] makes up for us much easier to defend our country especially from the sea and air… Basically, the Baltic Sea almost becomes the inner water of NATO.” Indeed, Russia faces now a bigger and more united rival, and can no longer count on the possibility of turning to Finland or Sweden when dealing with NATO nations. The Baltic Fleet will be under a much higher level of stress now. As Robert Farley puts it, “in no conceivable conflict could Russian warships (even submarines) use the Baltic without running the risk of imminent destruction.”

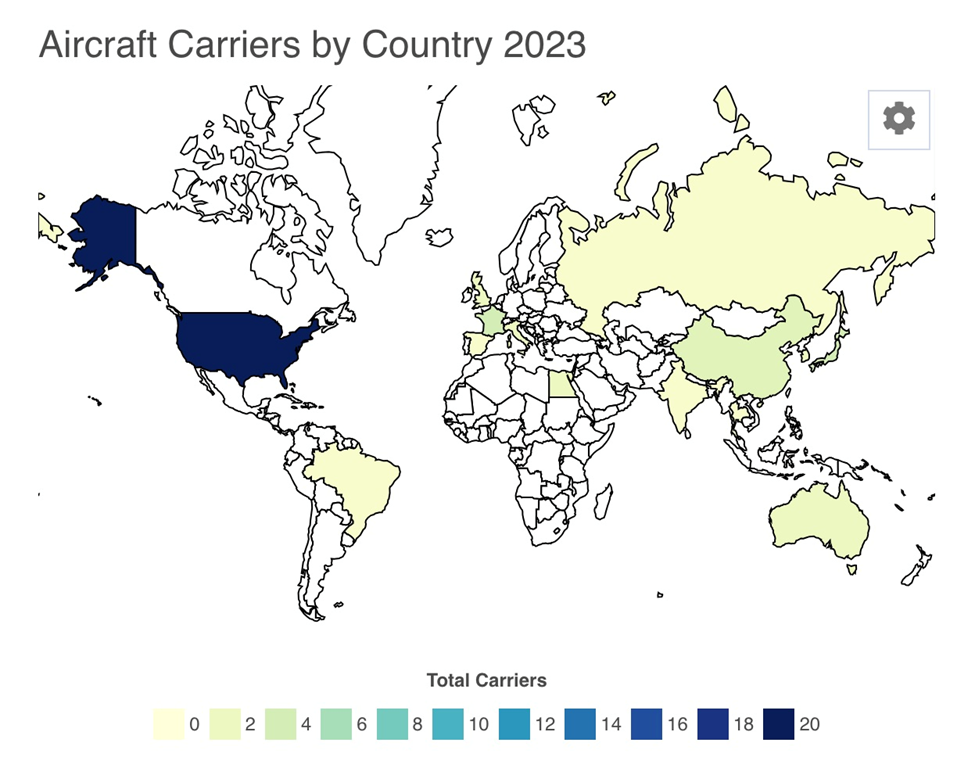

GASS adds that with only one aircraft carrier and with limited financial resources to build more, Moscow will have to cope with an increased NATO presence in the Baltic and the Arctic. Indeed with Finland as a neighbor, NATO is closer than ever to Russia’s Arctic military bases, including the ballistic missile fleet.

This flies in the face of the latest Naval Doctrine published a year ago, wherein Moscow clearly states it aims to become a global naval power. In fact because its one active carrier, the ‘Admiral Kuznetsov’, has had such a long history of complications and setbacks, GASS maintains Russia will be without an aircraft carrier until at least 2024, thus with no significant capacity to exert power in the world’s oceans.

In 2018, research began on nuclear engines for a new supercarrier nicknamed ‘Shtorm’, but it is expected to take a decade to build and cost around $5.5 billion.

In sum, GASS states, the Russian Navy will face a complicated period during the following years, with significant budgetary problems and a lack of assets to deploy into the high seas. The strategic shift in the Baltic region has left its fleet at Murmansk virtually helpless against a much bigger rival, and with Finland as a neighbor, NATO is now closer than ever to Russian northern bases in the Arctic. Although it will largely depend on the outcome of Ukraine and how its economy is left after that, it seems clear that the Russian Navy should not be a worrisome factor for NATO in terms of global naval power. Without a fleet of aircraft carriers,—which is the same as saying no carrier strike groups—the ambitions depicted in the recent doctrine will remain largely unattainable for Moscow.

The Arctic

As a result of what’s been happening in the Baltic and Black seas, Russia’s ability to move naval assets is now increasingly limited to the Kola peninsula, located in the far northwest corner of the country. The peninsula hosts Murmansk, the base of Russia’s nuclear submarines and much of its strategic missile force. Specifically, the Northern fleet’s headquarters and main base are in Severomorsk, Murmansk Oblast, with secondary bases elsewhere in the Kola Bay area.

However the location of these bases makes them far from ideal. Sea and ice conditions are notoriously difficult, and even with climate change opening up the polar seas, you still need icebreakers.

To deal with these challenges, Russia has been developing the world’s largest fleet of icebreakers, up to 40 vessels, which should put the Russian navy in a better position to control future commercial routes in the High North. In this sense, GASS states, Russia finds itself several steps ahead from the rest of NATO members in the region, some of which only have one or two icebreakers.

To put it into perspective, the Royal Canadian Navy has only two icebreakers active (adding to the 18 from the Coast Guard), and—more worryingly—the US has only three.

Playing to Russia’s Arctic strengths, Putin last year imposed increased responsibilities on the Russian navy, including the defense of the Northern Sea Route connecting Europe with Asia.

Submarine supremacy

It’s fairly common knowledge that the Arctic has long been a staging point for Russia’s seaborne nuclear deterrent capabilities, provided by the navy’s ballistic missile submarines (SSBMs).

According to one source, the sixth vessel of the ‘Borej’ class of smaller, stealthier ballistic-missile submarines, armed with 16 Bulava intercontinental ballistic missiles, has sailed to a temporary base in the Barents Sea. These submarines are intended to replace Russia’s previous generations of ballistic-missile submarines, many dating back to the Soviet era. (The Jamestown Foundation, Feb. 8, 2023)

According to the non-profit Nuclear Threat Initiative, Moscow has “significantly modernized its submarine force in recent years,” with 11 nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines and 17 nuclear-powered attack submarines.

Russia also has nine nuclear-powered cruise missile submarines and 21 diesel-electric attack submarines, says Newsweek. Recently, the head of Russia’s United Shipbuilding Corporation told state media that the navy would receive two new nuclear submarines by the end of the year.

Most military experts agree that Russia’s submarine fleet is the “critical challenge” to the US, and that, while older, they still pose a threat to NATO both at sea and against land-based targets.

However, while Russia’s subs are considered some of the best in the world (its ~58 vessels compare to the United States’ 64), their capabilities risk being diluted by Russia’s focus on the Ukraine war, which mainly involves land forces, and their future development jeopardized by Western sanctions. (Newsweek, May 3, 2023)

As for the surface fleet, the Russian navy has plans to launch new warships, with the lead ship in a new class of guided-missile frigates deployed to the North Atlantic in early January. As mentioned the one existing aircraft carrier, the Admiral Kunetsov, has been plagued by problems including several fires and the collapse of a crane. It hasn’t left port since 2017.

According to Business Insider, Russia has canceled procurement of additional patrol vessels over concerns about performance, and its two surviving battlecruisers ‘Pyotr Velikiy’ and ‘Admiral Nakhimov’, are old and have minimal ground-attack capability.

A comparison with the United States navy illustrates the Russian navy’s comparative disadvantage on the high seas. While on paper, it is actually bigger (i.e. has more ships) than the US navy, in terms of tonnage and war-making capabilities, it pales in comparison.

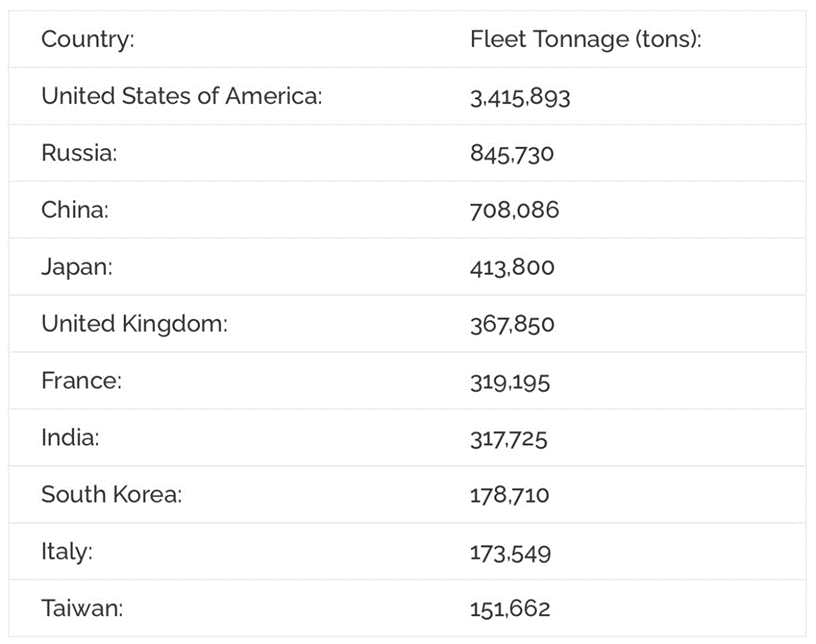

According to Migflug.com, for a long time the Russian navy was as big as the US one, however the annexation of Crimea provided Russia with 51 more ships, making it larger than America’s. But, the Russian navy is specialized to be used in canals and small seas (corvettes, for example), and has a much smaller battle fleet tonnage. As the table below shows, Russia’s fleet tonnage is four times smaller than America’s, which is bigger than the next 13 navies combined!

Conclusion

From this relatively brief analysis, it is abundantly clear that Putin’s plan to contain NATO has failed. In fact the accession of Finland and Sweden has added another 1,300 km of border with Russia, and turned the Baltic Sea into NATO’s backyard.

The situation is no better for Russia around the Black Sea. While Sevastapol used to be a safe port for Russian warships, Ukraine’s acquisition of British and French missiles brings the entire Crimean peninsula within range of its weapons. Arguably the safest place for Russia’s Black Sea fleet currently, is under sail.

Russia previously courted Turkey through the sale of an air-defense system but Ankara now realizes it’s better off sidling up to Europe, which offers a lot more in terms of foreign investment — important to its basketcase of an economy. Strategically, Turkey controls Russia’s access to the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean through the Bosphorous Strait.

The Russian navy maintains a powerful, and dangerous, fleet of nuclear-powered and armed submarines, but beyond these 50-odd vessels, its ability to project force overseas is extremely limited.

Consider: the Russian navy has just one decrepit aircraft carrier compared to the US navy’s 11, plus nine helicopter carriers. Without billions of dollars of investment into new equipment, which seems unlikely as long as Russia remains under Western sanctions, the Russian navy is at best a regional force — hemmed in by NATO countries, rebuked and isolated by its former friends.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.