The case for peak gold, silver and copper – Richard Mills

2022.11.27

The concept of peak gold should be familiar to most readers, and gold investors. Like peak oil, it refers to the point when gold production is no longer growing, as it has been, by 1.8% a year, for over 100 years. It reaches a peak, then declines.

Peak gold doesn’t necessarily mean gold production will suffer a major fall. However it does mean the mining industry lacks the capacity to ramp up production to meet rising demand; even higher prices would not make that happen, because there aren’t enough mines to tap for more supply.

If gold is indeed becoming scarcer, prices have only one way to go and that’s up, so long as demand for the precious metal is constant or growing.

In a previous article we proved peak mined gold in 2020.

The latest full-year World Gold Council report shows a 1% decline in total gold supply in 2021, compared to 2020, with a sharp drop in recycling more than offsetting higher mine production, which rose 2%, clawing back some of the pandemic-driven losses seen in 2020.

Recycled gold (jewelry) supply fell 11% year on year, a reaction to the modestly lower gold price in 2021 compared to 2020, when gold soared on account of pandemic-related fears, and record-low sovereign bond yields resulting in negative real interest rates — always bullish for gold.

According to WGC, mine production in Q4 2021 fell 1% yoy to 915t. This represented the lowest level of Q4 mine output since 2015. Annual production totalled 3,561t in 2021, 2% higher than 2020 but still lower than 2019 and 3% lower than 2018 — the year when the most gold ever was mined.

In calculating the true picture of gold demand versus supply, we at AOTH don’t count gold jewelry recycling. What we want to know, and all we really care about, is whether the annual mined supply of gold meets annual demand for gold. It doesn’t!

So, in 2021 total gold supply including jewelry recycling reached 4,666.1 tonnes. Full-year demand was 4,021 tonnes, propelled by Q4 2021 demand which jumped almost 50% to a 10-year high.

No peak gold here, right? Demand is more than satisfied by supply.

But when we strip jewelry recycling from the equation, 1,149.9t, we get an entirely different result. i.e. 4,021 tonnes of demand minus 3,560.7t of mine production leaves a deficit of 460.3t.

This is significant, because it’s saying even though major gold miners are high-grading their reserves, mining all the best gold and leaving the rest, they still didn’t manage to satisfy global demand for the precious metal, not even close. Only by recycling 1,150 tonnes of gold jewelry could 4,021 tonnes of demand be satisfied during 2021.

This is our definition of peak gold. Will the gold mining industry be able to produce, or discover, enough gold, so that it’s able to meet demand without having to recycle jewelry? If the numbers reflect that, peak gold would be debunked. We’ve been tracking it since 2019, and it hasn’t happened yet.

As gold mining companies struggle to keep up with demand, we at AOTH see nothing but blue sky ahead for the precious metal. How can we say that, when spot gold is down 2% year to date, amid six consecutive interest rate increases and a persistently high US dollar? (before the October bounce, it was down 7.8%)

Well, with the official US inflation rate at 7.7%, this is more than three times as high as the Fed’s normal 2% inflation target, suggesting more rate hikes are likely to come.

Remember: for the Fed to successfully fight inflation, it must set interest rates higher than the inflation rate. Former Fed Chair Paul Volcker broke the back of inflation, and caused a severe recession in 1982, by raising interest rates to twice the rate of inflation.

Personally I think the Fed may be forced to accept an inflation level higher than 2%, say 3%, precisely because food and energy are being left out of the official inflation rate, and because these are among the items that are becoming most expensive.

Surely for the broader CPI to fall substantially, food and energy costs must decline, but when I look at the energy crisis in Europe, UK food prices exceeding 10%, and OPEC’s 2 million barrels a day production cut keeping oil prices strong, I have my doubts whether this will happen anytime soon.

In our May 12, 2022 article, we identified five reasons why food will continue to get more expensive, and has: Soaring Fertilizer Prices; Lower Crop Yields; Rising Energy Prices; War in Ukraine; Monetary Policies & Stimulus Spending.

5 reasons why food will get more expensive

In Europe, historically high natural gas prices due to Russia’s severe NG export cutbacks, have forced shutdowns at energy-intensive businesses including steel and chemicals. Governments are reportedly issuing more debt to shield households and businesses from pain, and there are growing projections the energy crisis will spiral into a recession.

We also have to remember the toll, that the combination of high inflation and high interest rates is having on the average person. Many have got to the point where they’re living on their credit cards, in effect borrowing to keep spending, going ever deeper into debt.

A study quoted by Global News found Canadians are leaning more heavily on credit cards, amid higher inflation and despite rising interest on credit cards. Equifax Canada’s survey found the average credit card held by Canadians as of Sept. 30 was at a record-high $2,121. US credit card debt just hit an all-time high of $930 billion.

A stagflationary debt crisis looms

Each interest rate rise means the federal government must spend more on interest. That increase is reflected in the annual budget deficit, which keeps getting added to the national debt, now standing at a gob-smacking $31.3 trillion.

Considering that egregious over-spending with annual deficits exceeding $1 trillion is likely to continue, the question is who will fund the higher interest costs? The answer is investors, foreign and domestic, who buy US government bonds and notes, issued by the Treasury Department to fund government expenditures.

The problem is that right now, just about everyone is fleeing Treasuries, including emerging markets. Read more

The Fed, the debt, China and gold

If the regular buyers of US debt continue to stay away, it will fall to the lender of last resort, the Federal Reserve, to step in.

The key point is, the Fed can only push interest rates so high, without blowing up the Treasury and being forced into an aggressive bond-buying program (QE), thus accelerating inflation. The irony is that in trying to bring down inflation through interest rate hikes, the Fed, because of the high debt levels, will fail, and will be forced into a loose monetary policy involving interest rate cuts and QE.

In my opinion, precious metals’ positive reaction to lower inflation (Precious metals bounce is a taste of what’s to come) backs up what we’ve been saying about commodities for quite some time. It’s a prelude to what will happen across the entire commodities spectrum when the dollar finally weakens after months of strength.

Peak silver

Like gold, we can study the supply-demand picture for silver to get a sense of whether we’ve reached peak mine supply.

At AOTH we differentiate between the total silver supply, which lumps in recycled silver with mined silver, versus mine supply on its own. (most recycled silver is industrial grade)

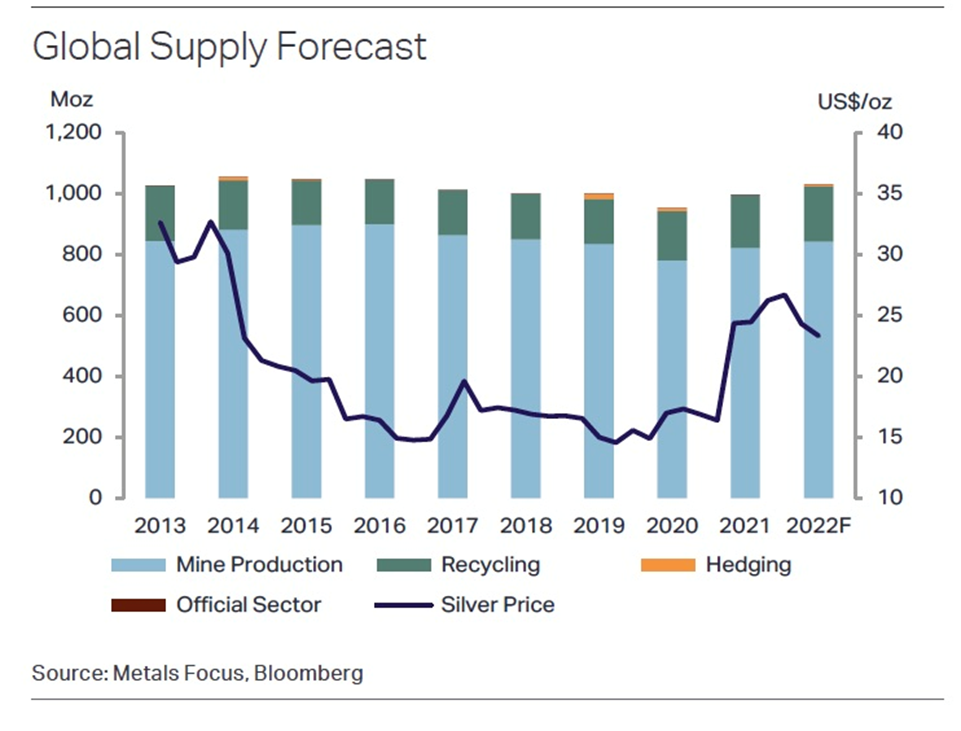

According to the 2022 World Silver Survey, in 2021 global mine production increased 5.3% yoy to 822.6 million ounces, or 25,587 tonnes. It was the biggest rise in production since 2013, largely due to economic recovery following a down year in 2020, when a lot of silver mines were disrupted due to the pandemic.

Helped by higher prices, silver recycling rose for a second year in a row, up 7% in 2021 to an 8-year high of 173Moz, or 5,382 tonnes.

Combined, therefore, we have total silver supply reaching 997.2Moz in 2021.

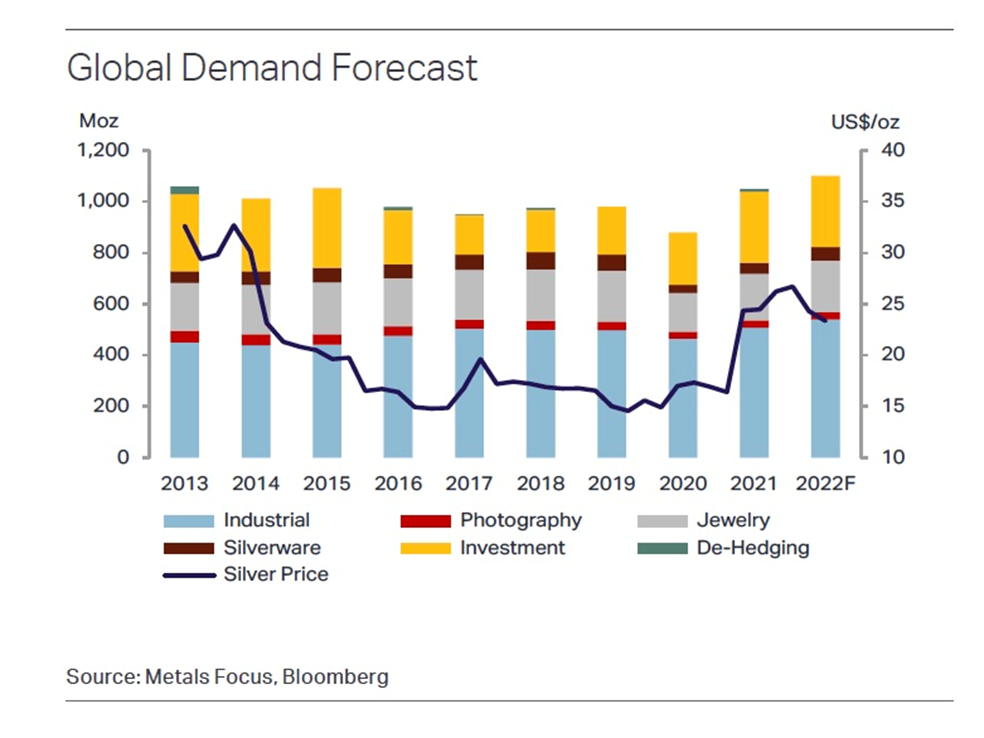

How about demand? According to the World Silver Survey, after a slump in 2020, global silver demand climbed by 19% last year to 1.05 billion ounces, surpassing pre-pandemic volumes and reaching its highest level since 2015.

(Remember: While most of the mined gold is still around, either cast as jewelry, or smelted into bullion and stored for investment purposes, the same cannot be said for silver. It’s estimated around 60% of silver is utilized in industrial applications, like solar panels and electronics, leaving only 40% for investing.)

All the demand categories saw gains, the largest being bar and coin purchases, followed by industrial demand. Physical investment (bars and coins) demand skyrocketed by 35% to 278.7Moz, the highest level since 2015’s record, as investors hoovered up the white metal in response to inflation uncertainty and negative real interest rates. Sales of silver bars and coins in India more than tripled.

2021 demand of 1.049 billion ounces outstripped supply of 997.2Moz, by 51.8Moz. But remember, recycling is included in the total supply. When we take recycling out, 173Moz, we get an even greater deficit of 224.8Moz. (1,049,000,000 minus 824,200,000 = 224,800,000)

This is significant, because it’s saying even though mined silver supply last year rebounded from 2020, to 822.2Moz, the highest since 2013, it was unable to meet total demand, industrial plus investment, of 1.05 billion ounces, which was the highest demand for silver since 2015. It fell short by 51.8Moz, and that was including recycling.

This is our definition of peak mined silver. Will the silver mining industry be able to produce, or discover, enough silver that it’s able to meet demand without having to recycle? If the numbers reflect that, peak mined silver would be debunked.

It didn’t happen in 2021, (or 2020) and according to the Silver Institute, it won’t happen in 2022 either.

Again, let’s look at the numbers.

The Silver Institute expects silver output in 2022 to exceed last year’s total by 2.5%, yoy, hitting 843.2Moz, or 26,226t. The biggest increases will be from Mexico and Chile, with the La Coipa Mine in Chile commissioned this past February and reaching full capacity mid-2023.

But again, this includes recycling; it’s set to increase for a third straight year, with a 4% gain forecast, or 180,500,000 oz.

Taking 180,500,000 oz of forecasted recycling out of the equation, we have mined supply of 662,700,000 oz, against the Silver Institute’s 2022 demand forecast of 1,101,800,000 oz (1.101Boz), leaving another forecasted deficit, and one that is nearly twice as larger as 2021’s, when recycling is excluded, of 439.1Moz.

Despite this year’s price weakness alongside gold, there are multiple reasons to believe that longer term, silver will rebound.

The potential forces behind silver’s next rally include: monetary demand, industrial demand, above-ground stocks, gold-silver ratio, silver-copper correlation, net short positions reduced, physical market tightness, and low inventory.

Moribund silver may soon have liftoff

Much of the bullish story is told on the demand side.

According to the Silver Institute’s 2022 Interim Silver Market Review, released on Nov. 17, global demand for silver this year is forecast to hit a record 1.21 billion ounces, a 16% increase from 2021 demand. New highs are predicted for physical investment, industrial demand, jewelry and silverware production.

While institutional demand for silver has faced headwinds, due to rising interest rates leading to a decrease in silver ETF holdings, this has been countered by a surge in physical investment, which is on pace to jump by 18% to 329Moz this year.

According to the Silver Institute, “Support has come from investor fears of high inflation, the Russia-Ukraine war, recessionary concerns, mistrust in government, and buying on price dips. The rise was boosted further by a (near-doubling) of Indian demand, a recovery from a slump last year, with investors often taking advantage of lower rupee prices.”

Evidence of high demand for silver is apparent from the decreasing amounts of silver in Comex vaults.

Earlier this month we reported that Comex silver inventories were at their lowest level since June of 2016.

Silver joining copper in upcoming supply crunch

Source: Gold Charts R Us

Total registered silver stocks on the Comex have dropped nearly 70% over the past 18 months, to 35,527,659 oz.

Industrial demand for silver, which makes up 60% of total usage, is expected to reach a new record in 2022, of 539Moz.

More and more silver is being demanded for use in solar photovoltaic (PV) cells, as countries adopt renewable energy sources. One projection has annual silver consumption by the solar industry growing 85% to about 185 million ounces within a decade, according to a report by BMO Capital Markets.

5G technology is set to become another big new driver of silver demand. Among the 5G components requiring silver, are semiconductor chips, cabling, microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), and Internet of things (IoT)-enabled devices.

The Silver Institute expects silver demanded by 5G to more than double, from its current ~7.5 million ounces, to around 16Moz by 2025 and as much as 23Moz by 2030, which would represent a 206% increase from current levels.

A third major industrial demand driver for silver is the automotive industry. Silver is found in many car components throughout vehicles’ electronic systems.

A recent Silver Institute report says battery electric vehicles contain up to twice as much silver as ICE-powered vehicles. Charging points and charging stations are also expected to demand a lot more silver. It estimates the sector’s demand for silver will rise to 88Moz in five years as the transition from traditional cars and trucks to EVs accelerates. Others estimate that by 2040, electric vehicles could demand nearly half of annual silver supply.

Additionally, demand for silver jewelry and silverware is projected to surge by 29% and 72% respectively.

These unprecedented demand pressures are not being met with substantially higher silver supply, either through mining or recycling. According to the 2022 Interim Silver Market Review, silver mine output will only chart a 1% increase in 2022, resulting in a second consecutive deficit this year: At 194 Moz, this will be a multi-decade high and four times the level seen in 2021. (Silver Institute news release, Nov. 17, 2022)

We use the gold-silver ratio to find out how silver prices compare to gold. The ratio is the amount of silver one can buy with an ounce of gold. Simply divide the current gold price by the price of silver.

Current indications show that silver is significantly undervalued. Right now the gold-silver ratio is 81:1, meaning it takes 81 oz of silver to buy one ounce of gold. The average is between 40:1 and 50:1, and historically, the ratio has always returned to the mean.

See the chart below, and linked commentary by Schiffgold.com, showing that Historically, when the spread gets this wide, silver doesn’t just outperform gold, it goes on a massive run in a short period of time. Since January 2000, this has happened four times. As this chart shows, the snapback is swift and strong.

Peak copper

The demand pressure about to be exerted on copper producers in the coming years all but guarantees a market imbalance, resulting in copper becoming scarcer, and dearer, with each infrastructure initiative and with each ambitious green initiative rolled out by governments.

The first problem is dwindling inventories.

Goehring & Rozencwajg, the Wall Street firm, recently published a chart of copper warehouse inventories showing a four-year down-trend from around April, 2018 to present.

Another problem is existing copper mines are running out of ore, and the capital being invested in new mines is far below the level needed.

According to research by S&P Global Market Intelligence, of 224 sizable copper deposits discovered in the past 30 years, only 16 have been found in the last decade.

It takes seven to 10 years, at minimum, to move a copper mine from discovery to production. In regulation-happy jurisdictions like Canada and the US, the time frame is more like 20 years.

The pipeline of copper development projects is the lowest it’s been in decades.

Why can’t we just mine more copper? Over the past two decades, the big mining companies have approached the problem of dwindling reserves by doing exactly that.

Between 2001 and 2014, 80% of new reserves came from re-classifying what was once waste rock into mineable ore, i.e., lowering the cut-off grade.

The problem is that between lowering their cut-off grades and high-grading (removing all the best ore and leaving the rest) the grade of new reserves each year has steadily declined.

In 2001, the new reserves grade was 0.80% copper but by 2012, it had fallen to 0.26%. The copper industry was still able to replace all the ore used in production with new reserves, but the quality of those reserves, i.e., the grade, had dropped by nearly two-thirds.

The authors of a 2021 report, Goehring & Rozencwajg, contend that even with prices above $10,000 per tonne, reserves cannot keep growing, specifically at porphyry deposits, where most copper is mined.

Their analysis also suggests that we are quickly approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades, concluding that we are nearing the point where reserves cannot be grown at all. In other words, peak copper.

Copper: the most important metals we’re running short of

The industry can no longer re-classify itself out of its problem. Billions and billions of dollars need to be invested in the exploration for, and development of new copper mines.

In sum, the copper industry is in the grips of a structural supply deficit that, combined with inflationary cost pressures and a creeping resource nationalism in some of the world’s largest copper producers, is only expected to get worse.

The world’s largest copper producer, Codelco, recently warned that global shortages of the metal could reach 8 million tonnes by 2032, as soaring demand fails to be matched by new copper mines.

In fact, the CEO of the Chilean state-owned company, Maximo Pacheco, parroted something that we at AOTH have been saying for months, that the transition to electric vehicles and renewable power will push demand for copper from 25Mt per year to just over 31Mt in 2032. That rate of increase is equivalent to building eight copper mines the size of Escondida, the largest in the world, per year, for the next eight years. (Escondida is so big, @ 1.4Mt annual capacity, it can produce more copper than the second and third largest mines combined, Chile’s Collahuasi @ 610,000 tonnes + Mexico’s Buenavista del Cobre @ 525,000t).

8 Escondidas needed over the next eight years

Unless new mining projects come into operation, Pacheco warned the imbalance between copper supply and demand will begin to be noticed in the second half of this decade, as early as 2026.

Earlier this year, Erik Heimlich, head of base metals supply at CRU, said the industry needs to spend more than $100 billion on new mines, to close what could be an annual supply deficit of 4.7Mt by 2030.

Conclusion

Gold, silver and copper all have supply challenges in common that suggest each has reached a peak level of mine production. For gold and silver, the mining industry is currently unable to mine enough to meet annual demand, without recycling.

In 2021, 4,021 tonnes of gold demand minus 3,560.7t of gold mine production left a deficit of 460.3t. This meets our definition of peak mined gold.

For silver, 2021 demand of 1.049 billion ounces outstripped mined supply of 997.2Moz, by 51.8Moz. This is our definition of peak mined silver.

The Silver Institute expects silver demand in 2022 to break a record, leaving another deficit, and one that is nearly twice as larger as 2021’s, when recycling is excluded, of 439.1Moz (It could be even larger. The 2022 Interim Silver Market Review has silver demand @ 1.21Boz, 8.9% higher than the Silver Institute’s earlier 1.10Boz forecast).

As for copper, we are quickly approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades, meaning that we are almost at the point where reserves cannot be grown at all. In other words, peak copper.

The copper industry is in the grips of a structural supply deficit that, combined with inflationary cost pressures and a creeping resource nationalism in some of the world’s largest copper producers, is only expected to get worse.

Global shortages of the metal could reach 8 million tonnes by 2032, as soaring demand fails to be matched by new copper mines. The rate of supply increases required, is equivalent to building eight copper mines the size of Escondida, the largest in the world, per year, for the next eight years. That’s insane.

When you combine the expected deficits for these three metals with increasing industrial demand for copper and silver (due to the greening of the world economy) and higher investment demand for silver and gold, once the Federal Reserve realizes it can’t raise interest rates any more without causing a recession, causing the US dollar to slide, the prices of gold, silver and copper are all but guaranteed to go up.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.