The case for palladium

Discovered by English chemist William Wollaston in 1803, palladium was named after the asteroid ‘Pallas’. The silvery-white metal is one of six platinum group elements (PGEs) found in the Periodic Table of the Elements. The others are iridium, osmium, platinum, rhodium and ruthenium.

Of all the PGEs, palladium is the least dense and has the lowest melting point.

Palladium is an uncommon element in the earth’s crust. Deposits of palladium and other PGEs are rare, with the largest occurring in South Africa’s Bushveld Igneous Complex covering the Transvaal Basin, the Stillwater Complex in Montana, the Sudbury Basin and Thunder Bay District of Canada, and the Norilsk Complex in Siberia. Recycled catalytic converters are also a source of palladium supply.

Applications

About three-quarters of palladium demand comes from catalytic converters. Also known as autocatalysts, these devices reduce noxious emissions, and have been an important reason for internal combustion engines (ICEs) polluting up to 90% less than they did in the 1970s, along with the tightening of US tailpipe emissions regulations, led by California.

Catalytic converters are supplied for diesel-fueled and gasoline engines. Both contain a mix of PGEs and other metals including platinum and palladium. A higher percentage of platinum is used in diesel autocatalysts, whereas gasoline autocatalysts have more palladium.

The lustrous metal is also used in electronics, surgical instruments, jewelry, watch-making, aircraft spark plugs, hydrogen purification and groundwater treatment.

Record-high prices

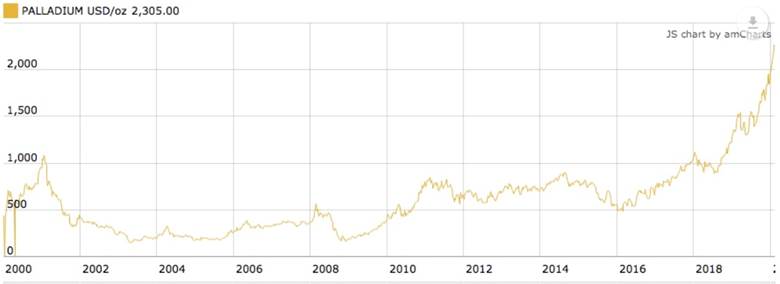

In January, palladium prices scaled heights not seen since 2008.

Spot palladium ran nearly 10% to $2,539 an ounce, and palladium futures also reached a record high of nearly $2,300/oz.

Why the enviable price performance?

Palladium has been in deficit for eight straight years, because of low mine output and smoking-hot demand for catalytic converters in gasoline-powered vehicles, as smog-belching diesel cars and trucks get phased out to meet tighter air emissions standards, particularly in Europe and China.

As car-makers shift from diesel- to gasoline-powered cars or gas-electric hybrids, the market for palladium-heavy autocatalysts has buoyed the price. In 2017 palladium raced past $1,700 an ounce for the first time since 2001.

Matching mine production with demand has become particularly problematic in South Africa, where palladium is mined as a by-product of platinum. Mining companies face higher costs per ounce as mines get depleted and they have to go deeper. Frequent labor unrest has also hobbled production.

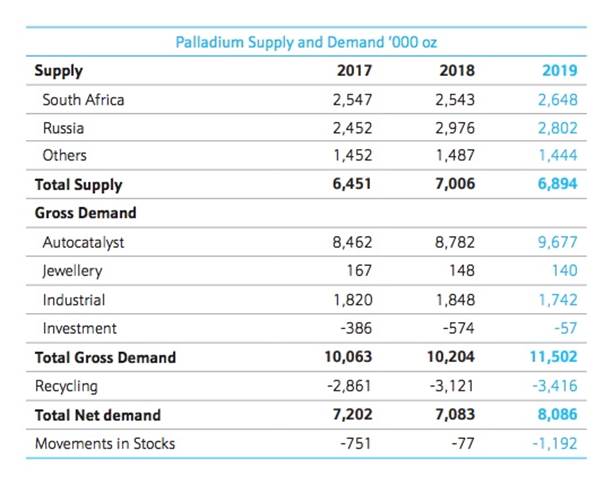

Last year the deficit widened to more than a million ounces, while demand hit an all-time high of 9.7Moz. Mine supply was only 6.3Moz, according to the US Geological Survey.

Despite a global slump in auto sales, palladium finished 2019 at $1,923 an ounce – far surpassing gold’s year-end close of $1,516/oz. As of this writing, palladium is trading at $2,310/oz, $728/oz higher than gold.

As long as the market remains in deficit, palladium prices are expected to remain buoyant, near term.

Smog control

Smog from vehicle emissions is estimated to cause a third of the air pollution in the United States. Despite greater environmental awareness and transit use, vehicles continue to emit a toxic cloud of air pollutants, caused by the burning of gasoline or diesel in the internal combustion engine. They are: carbon monoxide, expelled when the carbon in fuel doesn’t burn completely; hydrocarbons, a compound of hydrogen and carbon; nitrous oxides, a product of burnt fuel, created when nitrogen reacts with oxygen; and particulate matter, which consists of tiny soot particles that contribute to hazy skies and, when inhaled on a regular basis, can cause lung damage.

Health problems known to result from air pollution include asthma, heart disease, birth defects and eye irritation.

A 2019 study found over 30,000 Americans had died from diseases connected to air pollution in 2015, the latest year data was available.

According to Environmental Defense Fund, the transportation sector is responsible for 27% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. The sheer number of people that continue to drive and buy cars has offset pollution-control measures adopted by the auto industry, along with the growing popularity of hybrids, electric vehicles and renewable fuels – ethanol and biodiesel.

Despite dips during recessions, light vehicle sales per year in the United States have grown from about 15 million in 1978 to 17.2 million in 2018.

The US used to be the world’s biggest contributor of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, but in 2008 China took the ignoble top spot.

Cars being a status symbol, the Middle Kingdom has about 300 million vehicles registered. The Chinese government has taken steps to clamp down on air pollution and diversify into cleaner sectors, like solar and nuclear power, yet air pollution in China (and India) is horrific. A 2018 story in the South China Morning Post reported toxic air chokes around US$38 billion off the Chinese economy each year, due to early deaths and lost food production. Smog-inducing ozone and fine particles are destroying about 20 million tonnes of rice, wheat, maize and soybeans.

Autocatalyst demand

That sounds grim, but the auto industry has a secret weapon for fighting tailpipe emissions – catalytic converters, which in 1975 became mandatory for automakers to put into all new cars and trucks.

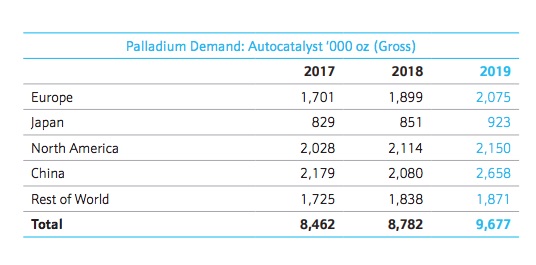

Autocatalyst demand accounts for three-quarters of the need for palladium. In 2018, out of a total market of 10.1 million ounces, catalytic converters used 8.6Moz, the balance going towards other industrial applications and jewelry.

Diesel phaseout

It used to be that diesel vehicles were sought after because diesel fuel was cheaper than gasoline. Many considered diesels no worse than gas engines for air pollution.

In 2016 the diesel car industry was shaken after Volkswagen admitted it had cheated on its emission tests. The “diesel-gate” scandal was made worse amid reports of the dangers of air pollution.

Diesel engines are therefore being phased out in favor of gas-powered cars and trucks that meet stricter emission regs.

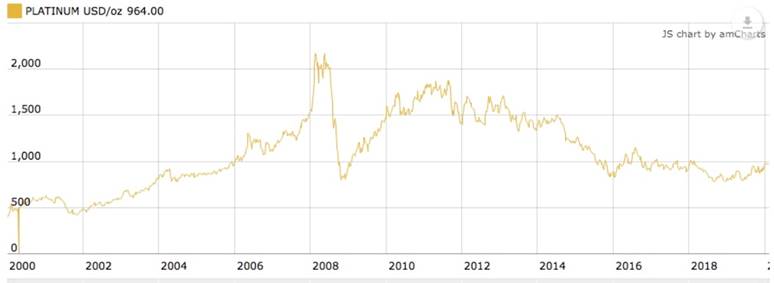

The move away from diesel has hurt not only diesel-car manufacturers but platinum. Less demand for diesel autocatalysts has weighed on platinum prices, which tumbled from a record $2,006 an ounce in 2008, to the current $964/oz.

Tighter emissions standards

Emissions control is critical in cutting down air pollution and mitigating the effects of heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions exiting tailpipes.

Concerns over air pollution led the EU to set a target of cutting emissions by at least 40% by 2030, from 1990 levels. The mayors of 10 European capitals are urging a switch to zero-emissions vehicles within the next 20 years.

Stuttgart, Paris, Mexico City, Athens and Madrid are all banning diesel fuel by 2030.

All passenger vehicles sold in Europe must now meet “Euro 6d” standards, showing they comply with NOx and particulate matter emissions.

The United States under President Obama embarked on a path of restricting auto emissions significantly, but the plans have skidded to a halt under the Trump administration.

China, whose major cities are often cloaked in a thick fog of air pollution, is targeting a reduction of between 26% and 28% of emissions from 2005 levels by 2030. The new rules demand that vehicles emit fewer pollutants such as nitrogen oxides, particulate matter and ammonia.

Beijing will implement its next round of carbon emission rules between 2020 and 2023, involving higher palladium and rhodium loadings, according to Johnson Matthey (JM), a UK-based chemicals company.

Palladium loadings jump

In its recent ‘Pgm Market Report’, JM says that Tightening emissions legislation and stricter vehicle testing regimes are driving up the pgm content of threeway catalysts [palladium, platinum and rhodium] in most major vehicle markets. Last year saw a 14% rise in global average palladium loadings on gasoline cars, with double-digit growth in both Europe and China. This propelled automotive demand for palladium to a new all-time high of 9.7 million ounces, a 10% gain versus 2018 despite falls in gasoline vehicle production in most regional car markets.

China was a key growth market for palladium autocatalysts. China 6 emissions legislation kicked in around the mid-point of 2019, prompting automakers to switch from Class 5-rated vehicles to the cleaner Class 6’s. The report says about 70% of new Chinese cars last year were rated Class 6 – a significant under-estimation of JM’s one-third prediction. Thus, despite falling car production in China, total palladium consumption rose about 20% in 2019. Palladium required for heavy-duty trucks in China also increased.

Meanwhile in Europe, the roll-out of Euro 6d-TEMP has been significant for palladium. Between 2017 and 2019 the PGE content of a European gasoline car rose by over 25%. Under the new legislation, automakers must ensure that emissions control equipment is effective under almost all conditions and for the life of the vehicle. As a result of Euro 6d-TEMP, JM estimated palladium demand in Europe last year reached a record 2.08 million ounces.

And there’s more to come. The final stage of Euro 6d kicked in this past January, meaning a further reduction in NOx emissions. JM therefore expects palladium loadings on gasoline catalysts will see another double-digit increase.

How electrification will strain metals supply

Whatever you believe with regard to global warming, there is no arguing that a reduction in our carbon footprint would benefit us all.

Electric vehicles, including cars, trucks, cargo vans and 18-wheelers, are the most promising technology to decarbonize America’s largest source of emissions, the transportation sector.

Bloomberg says there will be a 54-fold increase in electric vehicles between 2017 and 2040; the International Energy Agency predicts 24% annual growth until 2030. We’re not sure whether these targets are achievable. What we do know, is whatever the percentage of the total vehicle market EVs end up representing, there is going to be a long phase-in period.

It’s not only how quickly car-makers can crank out EVs and how soon consumers feel as comfortable buying one as a traditional model. It’s whether the raw materials can keep up.

In a recent article we asked: Given the current demands for copper, nickel, lithium and cobalt, do we have enough supply required for the construction of electric vehicles, and all the associated charging infrastructure? Is the massive shift required to move transportation from ICE vehicles to electrics setting ourselves up for a gigantic bust, as scarcity of raw materials pushes the prices of EVs beyond the reach of the average consumer?

The answer, we concluded, is it’s within the realm of possibility (though highly unlikely) for the mining industry to meet the metals demand required by a low-EV scenario of 14 million units by 2025, but anything beyond that is virtually impossible. Mark my words: motorists will still be pumping gas well into the 2030s.

Life still left in ICEs

Indeed despite reports of its imminent demise, the internal combustion engine isn’t going away any time soon.

A Reuters article quotes analysts saying it won’t be until the middle of this decade (or a lot longer) before electric vehicles overtake their gas and diesel predecessors; note that EVs only accounted for around 1.5% of the 86 million cars sold in 2018.

Hybrid bridge

As we move in the direction of more EVs relative to ICEs, there needs to be a transition period. Mass adoption of hybrids is the next step in getting to the target number. In both gas-powered cars/ trucks and gas-electric hybrids, palladium-rich autocatalysts can perform the crucial function of filtering air pollution.

According to Norilsk Nickel, which controls 40% of the world’s palladium production, palladium demand for hybrids is intensifying. Bloomberg says a market analyst at the Russian miner is forecasting that combined palladium use in hybrids (HEVs) and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) this year will be nearly triple that of 2016. In a report, JP Morgan predicts by 2025, hybrids will represent over 25 million vehicles, close to a quarter of all vehicle sales, compared to just 3% in 2016.

Supply crunch

South African palladium is a by-product of platinum mining, and palladium from Russia is a by-product of mining for nickel. Between them, the two countries control almost 90% of the palladium market.

While some palladium is found with gold and other PGEs in placer deposits, the two most important sources are the Norilsk-Talnahk deposits of Siberia, and the Merensky Reef PGE deposit in South Africa’s Bushveld Igneous Complex. Two other significant sources of palladium are the nickel-copper deposits of the Sudbury Basin, Ontario, and the Stillwater Complex, Montana.

Not only has demand bounced up, palladium is also facing constricted supply. 2019 was the eighth year in a row that palladium was in deficit.

The reason has mostly to do with structural supply problems in South Africa – although, as the Johnson Matthey report states, palladium supply declined by about 2% last year owing to lower shipments from Russia. (quarterly volumes have been volatile due to changes in Norilsk Nickel’s processing flowsheet)

South Africa’s platinum mining companies are under constant pressure to contain costs, because their mines are some of the deepest, hottest and most labor-intensive in the world. Many aging shafts are being closed, lowering PGE production. They also face frequent strikes. In 2014 workers at the country’s three major producers – Lonmin (acquired in 2019 by Sibanye-Stillwater), Anglo American Platinum and Implats – downed tools for five months demanding that wages be doubled.

There are significant infrastructure constraints hobbling production growth at South African mines. The country has limited processing capacity, frequent problems deploying enough power (brownouts and blackouts are common), and water is a constant concern.

Last year Implats took a big step in diversifying its risk away from South Africa by acquiring Canada’s North American Palladium Inc. (NAP) for $753 million. NAP is one of two primary palladium producers globally. The other, Stillwater Mining and its palladium mine in Montana, was bought by another South African company two years ago, Sibanye-Stillwater.

As for the situation in 2020, Johnson Matthey is forecasting a deepening of the supply deficit. The reasons, outlined in the report, include:

- An increasing number of vehicles in Europe and China having to meet Euro 6d and China 6 emissions legislation, which will drive up palladium loadings on gasoline catalysts, and lift automotive demand above 10 million ounces (remember world mine supply last year was only 6.3Moz)

- A fall in supply from South African mines and depletion of palladium-rich surface materials at Norilsk Nickel.

- Limited processing capacity at Norilsk Nickel’s Talnakh and South Cluster mining operations – a concentrator expansion is planned for 2023.

No substitutes

Some have suggested that platinum could be substituted for palladium if palladium prices continue to trade significantly higher than platinum prices. The problem however is supply. Both metals are looking at long-term structural supply deficits even though investment demand for platinum was piqued last year due to the negative interest rate environment globally (JM says +1 million ounces were added to ETF holdings, outweighing a contraction in industrial demand and a double-digit drop in the Chinese platinum jewelry market, due to a fashion shift to gold jewelry)

It has also been said that palladium-heavy catalytic converters perform better than platinum under extreme-conditions emission tests, and that switching to a platinum-based autocatalyst would be too expensive.

JM acknowledges in its report that there is some short-term potential for “thrifting” (reduced usage) and substitution in the automotive industry, but this is unlikely to be enough to prevent demand from rising again in 2020, with both Europe and China expected to see further increases in average palladium loadings on gasoline cars this year.

Other key statements from JM regarding palladium substitution:

We do not currently expect any significant substitution of palladium in gasoline autocatalysts in 2020…

[G]iven current trends in loadings, it would require quite significant uptake of platinum-rich gasoline catalysts to halt the rise in global palladium demand, let alone begin to reverse it.

Amid these tight market conditions, which will remain so for the foreseeable future in the absence of new palladium deposits, and as long as gas-powered vehicles and hybrids keep rolling off assembly lines, companies that mine palladium are well-positioned to make gains, in light of bullish price expectations.

And considering the difficulty the world’s largest palladium miners, especially those in South Africa, are having increasing production, the onus is on smaller companies to find and develop new deposits of the platinum-group elements.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.