Some say China isn’t driving the next commodity super-cycle. We beg to differ

2022.04.14

The new “commodities super-cycle” touted by many including Goldman Sachs, may be tied to the infrastructure deficits many countries need to try and reduce, along with the global threat of climate change, the evidence for which is growing stronger each year, and is driving economies to rapidly shift away from carbon-emitting energy sources to low-carbon or carbon-free alternatives.

China, however, is the elephant in the room that should never be forgotten, or underestimated. Despite keeping a lower profile when it comes to commodities consumption than during the last super-cycle, from 2003-11, arguably it will continue to need more commodities than the rest, for traditional “blacktop” infrastructure (think roads, bridges, airports, etc.), green projects needing a broad range of electrification/ decarbonization metals, and to feed an expanding, and evolving, manufacturing base.

The premise of this article is that China is entering a new phase of its economic growth, dominated by manufacturing. Now that the country has done all it needs to do to urbanize, and having acquired the metals, indeed locked up most of the world’s minerals, to build the infrastructure for its “Belt and Road Initiative”, China’s next mission is to become the world’s high-tech manufacturing hub.

Commodity super-cycles

Since the mid-19th century there have been four super-cycles, defined as “decades long, above trend movements in a wide range of base material prices.” The last one was the 2000’s commodities boom, driven by China’s insatiable hunger for fuels, metals, building materials and foodstuffs, as its economy grew at double digits. From the bottom in 2003 to the peak in 2008, commodities rose over 300%.

Many are pointing to the formation of a new super-cycle, driven not by fossil fuels and the rise of China, but by “green” metals needed for technologies that mitigate the negative effects of climate change.

On top of surging demand for metals needed to feed so-called green infrastructure programs being pursued by the United States, Europe and China, we have current and emerging structural deficits for several metals, that will keep prices buoyant for the foreseeable future.

Over the past year, for example, tight supply is reflected in the rising prices of copper, nickel, zinc, lead and aluminum.

Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research for Goldman Sachs, in January reiterated his (and the bank’s) view that we are at the beginning of a decade-long commodity super-cycle.

Currie is especially bullish on metals. Bloomberg has him declaring copper “the new oil”, noting it’s indispensable in global decarbonization strategies with copper shortages already being felt.

Other clean energy experts share Currie’s views.

New energy research outfit Bloomberg New Energy Finance says the energy transition is responsible for driving the next commodity super-cycle, with immense prospects for technology manufacturers, energy traders, and investors. Indeed, BNEF estimates that the global transition will require ~$173 trillion in energy supply and infrastructure investment over the next three decades, with renewable energy expected to provide 85% of our energy needs by 2050.

Clean energy technologies require more metals than their fossil fuel-based counterparts. According to a recent Eurasia Review analysis, prices for copper, nickel, cobalt, and lithium could reach historical peaks for an unprecedented, sustained period in a net-zero emissions scenario, with the total value of production rising more than four-fold for the period 2021-2040, and even rivaling the total value of crude oil production.

A net-zero emissions scenario could see a 4-fold increase in the value of metals production, totaling $13 trillion over the next two decades for copper, nickel, cobalt and lithium alone. This would rival the value of oil production over the same period.

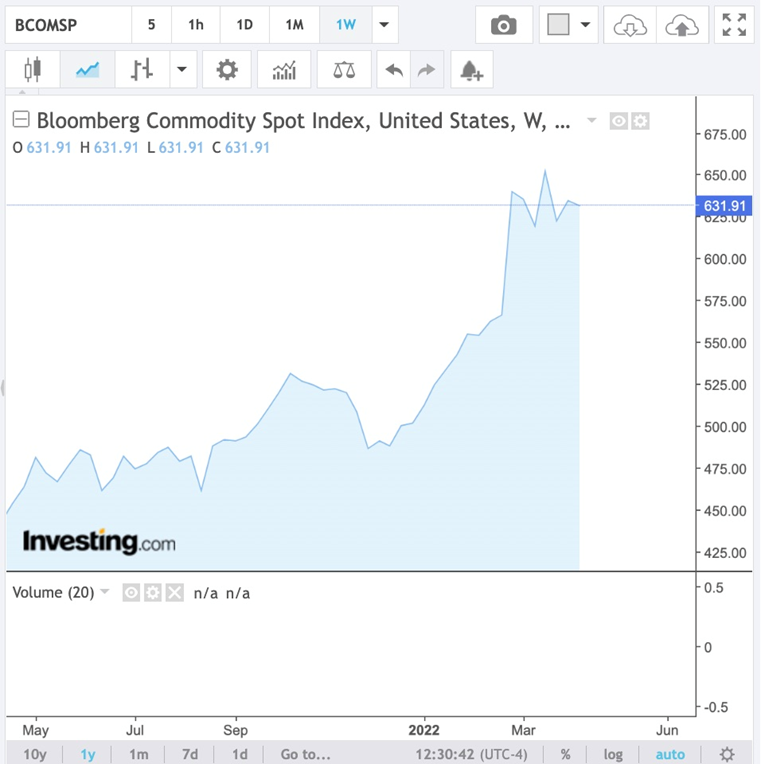

Referring to the Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index, which hit a new record earlier this year, driven in part by surging oil prices, Currie said he’s never seen commodity markets pricing in the shortages they are right now.

“I’ve been doing this 30 years and I’ve never seen markets like this,” the commodity expert said in a Bloomberg TV interview. This is a molecule crisis. We’re out of everything, I don’t care if it’s oil, gas, coal, copper, aluminum, you name it we’re out of it.”

Lingering supply chain issues from covid and the war in Ukraine have made these pressures even stronger.

Nickel prices spiked following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, a major supplier of the base metal through state-owned miner Norilsk. The war has also sent the prices of wheat and fertilizer on a tear, the latter rising even before the conflict due to the soaring price of natural gas used to make it.

Eating our lunch

Just over a year ago President Biden said that Beijing’s infrastructure investments were far outpacing Washington’s and that his $1 trillion infrastructure package, then under Senate consideration, now passed into law, was necessary to keep the US ahead of China. He quipped that without similar investment, “China is going to eat our lunch.”

Well Joe, I hate to break it to you, but China has already eaten our (the US’s) lunch, breakfast and dinner; to stretch a metaphor, the country has pretty much bought the entire grocery store.

China, the world leader in electric vehicles and battery production, is moving forward rapidly on its plans to electrify and decarbonize. President Xi Jinping in 2020 announced the country is aiming for carbon neutrality by 2060. (carbon neutral means emitting the same amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as is offset by other means)

The country says it will boost the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25% by 2030.

The Made in China 2025 initiative seeks to end Chinese reliance on foreign technology by investing in a number of key sectors, including IT and robotics.

Both “MIC2025” and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are part of Beijing’s most recent Five-Year Plan, which calls for developing and leveraging control of “core technologies” such as high-speed rail, power infrastructure and new energy, all of which require extensive minerals.

While the United States in November passed a trillion-dollar infrastructure package that includes, among other things, money for roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, China is looking to outspend it by a large margin.

At Beijing’s behest, local governments have reportedly drawn up lists of thousands of “major projects,” which they’re being put under intense pressure to see through. Planned investment this year amounts to at least 14.8 trillion yuan (US$2.3 trillion), according to a Bloomberg analysis.

That’s more than double the new spending in the infrastructure package the US Congress approved last year, which totals $1.1 trillion spread over five years.

Notably, the composition of the stimulus spending will be less on infrastructure than manufacturing, including factories, industrial parks and technology incubators. The construction push is part of the central government’s plan to meet its targeted 5.5% growth rate this year.

Read more about China’s manufacturing plans below, but for now, let’s look at how much of a challenge it will be for the United States to keep up to China.

From 2011 to 2013, China poured more cement than the US did in the entire 20th century. Politico neatly summarizes the differences in scale between the two countries, when it comes to infrastructure investment, noting that:

- China spent about $8 trillion on infrastructure investment in 2020. The US spent $146 billion in federal money over the same period.

- A comparison of 2018 infrastructure spending a percentage of GDP by 48 OECD countries ranked China first at 5.57% compared to 0.52% for the US.

- Its 2021 budget alone allocated $94 billion in spending for “new projects” that include “the development of new infrastructure.”

- The Biden plan allocates $66 billion to Amtrak passenger rail. China grew its rail network by 21% to 91,000 miles between 2015 and 2020 and plans to build another 31,000 miles of track by the end of 2035. That will put China on a path to surpass the 161,000-mile rail network in the US by the middle of the century.

- China intends to extend its expressway system 47% by 2035. That growth will extend China’s expressway network to 124,000 miles, surpassing the size of the current US expressway network of 98,000 miles.

- The US currently has 42,000 public EV charging stations, compared to China’s 1.68 million.

- New York’s La Guardia Airport is currently undergoing a $4 billion renovation. Last year the Chinese government announced that it will build 162 new airports by 2035.

- The infrastructure bill directs $65 billion to create nation-wide broadband internet access. In China, 98% of the country’s rural communities have access to fiber optic or 4G broadband internet service.

Not only has China outspent the United States and led the world on infrastructure investments, it has also worked relentlessly over the past decade to lock up the world’s metals, creating import dependencies for a number of key minerals in the US and other Western countries.

Copper is a good example.

In a previous article we showed that four out of the five major copper projects in the pipeline right now either have offtake agreements in place with non-Western countries (South Korea and China), or the mines are partially owned by Japanese companies that have a say in where some of the mined copper is destined. (i.e. Japan).

We make a clear distinction between global copper supply and the global copper market. Mined copper that is locked up by offtake agreements should not rightly be lumped in with global supply, because it will never reach the United States, Canada or Europe. Instead, this copper will go straight to smelters in China for use in Chinese industry, to South Korean smelters for South Korean industry, and to Japanese smelters for Japanese industry. We can hardly call this situation Western security of supply, when most of the raw copper material (cathodes or concentrate) is going to China, South Korea and Japan, who then turn around and sell more expensive copper end products to North America and Europe.

At Ivanhoe Mines’ massive Kamoa-Kaukula copper mine in the DRC, which recently came online, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project.

China long ago put a lock on much of Africa’s vast resources. Within a decade, the number of major mines or mineral processing facilities with China-headquartered companies rose from a handful in 2006 to more than 120 in 2015.

We know from previous articles that China has been extremely active in acquiring ownership or part-ownership of foreign lithium mines and inking offtake agreements.

China of course, has also monopolized rare earths and is the main player in a number of critical mineral markets including cobalt, graphite, manganese and vanadium.

For years the United States and Canada didn’t bother to explore for these minerals and build mines. Globalization brought with it the mentality that all countries are free traders, and friends.

China recognized opportunity knocking and answered the door, seizing control of almost all REE processing and magnet manufacturing, in the space of about 10 years.

As part of its US-China trade war strategy, China raised the prospect of restricting exports of these commodities, that are critical to America’s defense, energy electronics and auto sectors.

Currently nearly all graphite processing takes place in China because of the ready availability of graphite there, weak environmental standards and low costs.

Over half of the world’s cobalt — a key ingredient of electric vehicle batteries — is mined as a by-product of copper production in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In a $9 billion joint venture with the DRC government, China got the rights to the vast copper and cobalt resources of the North Kivu in exchange for providing $6 billion worth of infrastructure including roads, dams, hospitals, schools and rail links.

Often China’s modus operandi is to build mines in exchange for providing infrastructure that supports, and gains the favor of, the local population, such as schools, health clinics, roads and clean water systems.

China controls about 85% of global cobalt supply, including an offtake agreement with Glencore, the largest producer of the mineral, to sell cobalt hydroxide to Chinese chemicals firm GEM. China Molybdenum is the largest shareholder in the major DRC copper-cobalt mine Tenke Fungurume, which supplies cobalt to the Kokkola refinery in Finland. China imports 98% of its cobalt from the DRC and produces around half of the world’s refined cobalt. Of 14 large cobalt mines, up to eight have tie-ups with Chinese companies.

Most of the metal produced under these offtake agreements will never come to the market anyplace other than in China. Those metals that do, can have their supply shut down any time the Chinese want.

Over the past few years, overt resource grabs by China in what used to be the US backyard, countries defined by ‘The Monroe Doctrine’, include:

- Shandong Gold partnered with Barrick Gold to purchase a 50% stake in the Veladero gold mine on the Chile-Argentina border for $960 million.

- Two large Peruvian copper mines are owned by Chinese companies. State-run Chinalco owns the Toromocho copper mine, while the La Bambas mine is a joint venture between operator MMG (62.5%), a subsidiary of Guoxin International Investment Co. Ltd (22.5%) and CITIC Metal Co. Ltd (15%). The Chinese-backed Mirador mine in Ecuador opened in 2019.

- In 2018 China’s Tianqi Lithium purchased a 23.7% stake in Chilean state lithium miner SQM, despite concerns from regulators that the $4 billion tie-up would give Tianqi a near monopoly over the lithium market and unprecedented pricing power.

China’s most recent foray into overseas minerals acquisition involves Indonesian nickel.

Tsingshan, the world’s largest stainless steel maker, plans to construct an Indonesian plant to produce nickel-cobalt salts from nickel laterite ores. Using previously uneconomic high pressure acid leaching (HPAL) technology Tsingshan says it will transform class 2 laterite deposits into class 1 metal for the electric vehicle battery market.

In April 2021, Chinese battery maker CNGR announced it will buy nickel matte, used to make EV battery chemicals, from Tsingshan’s $243 million smelting project on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

A month later, China’s Lygend Mining and its $1 billion nickel and cobalt smelting operation became the first project in the southeast Asian country to reach full production.

The venture is the latest among several cobalt-nickel HPAL plants in Indonesia that are under the spotlight as a source of supply for the burgeoning electric-vehicle battery sector. The country banned nickel ore exports from the start of 2020 as it sought to establish a fully integrated battery industry at home. It later lifted the ban, but plans on re-instituting it in the middle of 2023.

But China doesn’t care about that. Its goal is to establish a nickel processing beach head in the world’s largest nickel producer, using Chinese technology to process class 2 nickel laterite deposits into class 1 battery-grade metal. Then sell its nickel chemicals to battery companies either in China or Belt and Road countries, as it continues on its path to complete global metals domination.

Belt and Road

To understanding why China is now turning its attention to manufacturing, in particular high-tech industries, we first need to know about the Belt and Road Initiative, also known as “One Belt One Road”.

Beijing is actively promoting the $900 billion program to open channels between China and its neighbors, mostly through infrastructure investments.

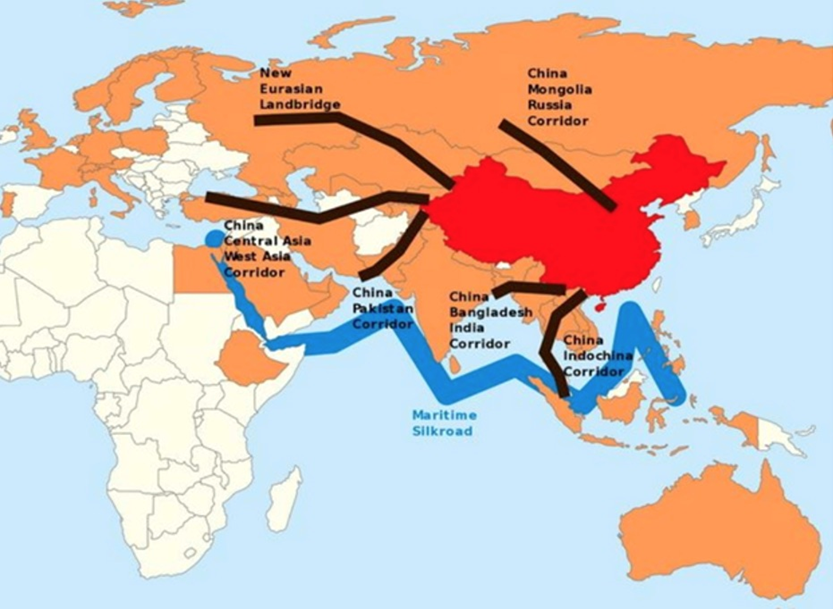

The “Belt” part of the Belt and Road Initiative, introduced by President Xi Jinping in 2013, refers to a network of overland road and rail routes and oil/ natural gas pipelines planned to run along the major Eurasian land bridges: China-Mongolia-Russia, China-Central and West Asia, China-Indochina peninsula, China-Pakistan, Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar. They’ll stretch from Xi’an in Central China through Central Asia, reaching as far as Moscow, Rotterdam and Venice.

The “Road” is a network of ports and other coastal infrastructure projects from South and Southeast Asia to East Africa and the northern Mediterranean Sea.

Then there is the “Polar Silk Road” which currently goes over Russia but also includes Canada as a short cut to Europe, thanks to global warming melting polar ice and facilitating global shipping through the Arctic.

An Asia geopolitical expert says that, while the BRI satisfies a number of economic goals for China, including expanding its supply chains, accessing overseas labor, and preventing layoffs when companies run out of domestic infrastructure to build, the over-riding goal is regional influence.

The result is what one observer aptly described as “debt-trap diplomacy”, since some nations end up piling up unsustainable debts to China.

China’s idea is for Chinese state-owned firms to build the infrastructure, paid for by participating countries. Those who can’t afford it, and that is most of them, are offered inexpensive loans and credit. It’s no different from banks offering rock-bottom interest rates to homeowners whose incomes are below that needed to support a mortgage.

In 2017, when Sri Lanka couldn’t pay off its Chinese creditors, Beijing took control of Colombo, a strategic port, through a 99-year lease. By the end of 2018, nearly a quarter of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt was owed to China — the money accepted for around $8 billion worth of ports and highways planned through BRI. Read more here

The Northern Miner’s recent expose on BRI (paywall) reveals that it currently revolves around 130 countries. One Belt One Road features six “Economic Corridors” which include rail, road and telecom infrastructure supported by energy and resource development. The country has reportedly spent between US$500 billion and $700 billion on these corridors to date, with spending currently averaging about $100B a year.

A major focus is the China Pakistan Economic Corridor, where $40 billion has been spent and $65B is promised. It opens a route from southwest China to the Indian Ocean at the newly built port of Gdawar.

The “New Eurasia Land Bridge,” meanwhile, offers a direct rail connection from Yiwu, near Shanghai, to Western Europe. By 2020 the article says it was carrying around 300 trains per day.

A few more interesting points:

- According to estimates by McKinsey and other consulting groups a total of between US$4 trillion and US$8 trillion will be spent on the BRI by 2049, the centenary of the Communist Party.

- The big winners have been the major state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as China Communications Construction Corp., China Harbor Engineering Corp., China Railway Engineering Corp., State Grid Corporation of China, Sinopec, CNOOC, major Chinese banks, and China Mobile, and “public” firms such as Huawei and Alibaba.

- In the mining sector beneficiaries have been the companies we know well in Canada such as Minmetals, Zijin Mining, MMG, Shandong Gold, Jilin Jian, Jiangxi Copper, Chalco, Jinchuan, China Non-ferrous, Wisco, Metallurgical Corporation of China, among others.

- The BRI countries with the largest project commitments (2005-19) are, in order, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Indonesia, UAE, Ethiopia, Russia and Algeria.

- The China-Pakistan Corridor is the flagship BRI project and the largest by far at an announced total commitment of US$65 billion.

- According to the U.S. Bureau of Mines, China held a dominant production position globally last year in a range of critical minerals: rare earth elements (58%), gallium (97%), germanium (66%), tungsten (82%), tellurium (61%), graphite (59%), and silicon (68%).

Ag Metal Miner, via Oilprice.com, gets into the question of how will China’s BRI will impact critical metal supplies, noting that China has arrangements with a number of countries to shore up its own mineral reserves.

Examples include a new trade deal between China and Ecuador, and Zijin Mining announcing that it will invest $380 billion to build a lithium carbonate plant in Argentina.

Zijin has also launched its first lithium exploration project in the DRC, through Katamba Mining, a JV between Zijin and Congo-based COMINIERE.

The manufacturing imperative

Now that China has secured most, if not all, of the minerals it needs to create what is essentially its own trading ecosystem with BRI member countries, the work is beginning on how to build a manufacturing base from which to generate a huge range of products to sell to them.

It’s important to recognize that these aren’t the Chinese goods of old. No more cheap plastic toys and kitchen appliances. Statements from China’s leadership indicate the country is moving into high-technology sectors that will lead the world and relegate the US to second place.

In describing the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’, President Xi clearly indicated that China will move away from its previous economic trajectory beginning in 2021, stating that “we must strive to promote the common prosperity of all people and achieve more obvious substantive progress. … [We must] no longer simply talk about heroes based on the growth rate of GDP.”

The plan outlines a number of policies that are designed to support the development of scientific research and advanced manufacturing. According to the Hong Kong Trade Development Council, the Chinese government is looking to target such cutting-edge fields as: artificial intelligence (AI), quantum information, integrated circuits (ICs), life and health, brain science, biobreeding, aerospace technology, deep earth and deep sea, and implement a series of forward‑looking and strategic National Science and Technology Major Projects. (2.4.2) Support will also be given to Beijing, Shanghai and the Guangdong‑Hong Kong‑Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) to establish global technology innovation centres, and to Huairou of Beijing, Zhangjiang of Shanghai, the GBA and Hefei of Anhui to develop comprehensive national science centres.

The South China Morning Post reported in January that China is fast-tracking 102 major infrastructure projects in 2022, despite economic headwinds from last year’s power supply crunch and the lingering effects of the pandemic.

The newspaper explains that previously, building more highways, railways and airports, the traditional “black top infrastructure” were seen as a way to stabilize the economy, but they resulted in a large increase in local government debts amid unregulated spending sprees.

Beijing has therefore taken steps to prevent these debts and is advocating for so-called “new infrastructure”, including 5G, ultra-high-voltage power transmission, big data centers, industrial internet and artificial intelligence.

Towards this goal, the Ministry of Finance has allocated US$188 billion worth of bonds, that local authorities are urged to issue, to fund construction projects and to leverage private investment.

“The government is paying great attention to the manufacturing sector and the real economy — we can feel that,” the general manager of Tianjin Langyu Robot Co, told Reuters in a feature story last September on the topic.

Beijing reportedly wants to avoid the “middle income trap”, which can happen when countries lose productivity and focus too much on lower-value economic output, such as the services sector (which is what the US economy is mostly based on). The country is therefore backing R&D efforts by high-tech manufacturers, driven by an urgent desire to reduce reliance on imported technology and reinforce its dominance as a global factory power, even as it cracks down on other parts of the economy [like real estate, internet technology and polluting industries].

The Chinese government was also motivated, in its efforts to step up advanced manufacturing, by the trade war with the US which exposed China’s lack of high-tech knowledge.

Apparently Beijing does not want manufacturing to fall below 25% of GDP, as it did in 2020 (21.8%). The plan to boost R&D spending by over 7% annually will focus on “frontier” technologies such as AI, quantum computing and semi-conductors, Reuters said. It also targets nine emerging industries: new-generation information technology, biotech, new energy, new materials, high-end equipment, new-energy vehicles, environmental protection, aerospace and marine equipment.

Conclusion

A lot of people in the West laughed at China’s ghost cities when the phenomenon first became known. In the same way that the public loves to see celebrities humiliated, we reveled in smug satisfaction at how our emerging economic rival had overextended itself, in its earnest attempt to reach urban parity with North America and Europe.

Well China could have the last laugh. As Beijing goes about reinvigorating its manufacturing sector, shifting gears from a consumer-oriented service economy to one based once again on goods — not cheap exports bound for Wal-mart but high-value industries that produce things like AI, quantum computing and semi-conductors — all of those ghost cities with empty apartment blocks will soon be occupied by new-economy workers. Many of whom either work from home or make a short commute by electric vehicle, e-bike or in the future, an automated vehicle, to the factory/ business center conveniently built within close proximity.

It wouldn’t surprise me to see China fill these “stranded assets” with workers and build their advanced manufacturing base around them. It makes total sense and was likely their plan all along.

Look: China has already locked up most of the world’s metals, either through the purchase of mines by sovereign wealth funds, taking stakes in existing mines, or signing offtake agreements.

China long ago monopolized rare earths and is the main player in a number of critical mineral markets including cobalt, graphite, manganese and vanadium.

China has not only run circles around US mining, effectively drawing end-users into a precarious web of import dependence, Beijing has outspent the United States by a long shot and leads the world on infrastructure investments.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a clever way of making itself independent of the global economy and the US dollar reserve currency that most commodity trade are settled in. Through BRI, China will have a trading ecosystem of 130 countries, many of which will be indebted to it. It’s hard to negotiate favorable terms of trade when your country’s entire infrastructure has been financed by the Chinese government.

Spending on China’s six Economic Corridors will average about $100 billion a year. According to estimates by McKinsey and other consulting groups, between US$4 trillion and US$8 trillion will be spent on the BRI by 2049.

By mid-century the idea of a trade war between China and the US will be laughable, since China will no longer need the United States or any of its current Western trading partners. Remember, the BRI countries currently with the largest project commitments are Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Indonesia, UAE, Ethiopia, Russia and Algeria. None of them are Western and none will, imo, give a damn about human rights abuses, having an apparatchik President entrenched for life, or for that matter, worry about following WTO rules of international trade.

I envision a new world order (for a very large majority of the world’s population) ruled by China, where China owns all the minerals and distributes them as they see fit, provides all the infrastructure, that it has built, and will continue to build, for its Belt and Road client states, and in future, is an advanced manufacturing hub that the rest of the world depends on for everything from information technology, biotech and new-energy vehicles, to environmental protection, aerospace and marine equipment.

In many ways this is already happening. Several Western countries consider Huawei to be a trojan horse for the Chinese government, but the company has finalized more 5G contracts than any other telecom company, half of which are in Europe. In Africa, according to the Council for Foreign Relations, Huawei has built 70% of its 4G networks.

One in three of the world’s unicorn companies (the term given to privately held start-ups valued at over $1 billion) are now Chinese. The country also accounts for 50% of global digital payments and three-quarters of the global online lending market.

China now has the second-largest AI market after the US, and PwC predicts that AI technologies could contribute a 26% boost to GDP by 2030…

One area which has seen huge growth in recent years is FinTech. This trend has been propelled forward by a tech-savvy younger generation, the move towards a cashless society and a demand for services often not provided by big state-owned banks, such as easily accessible finance plans for small businesses and individuals. FinTech investments in China increased by 252% from 2010 to 2016, by which time the value of China’s mobile payments by individuals totalled $790bn – 11 times more than the US.

China understands that mining is the lynchpin, that enables an economy to move from low-tech producer of inexpensive goods for export, to high-tech manufacturer of goods and services the future world economy needs. Because they have the raw materials.

It’s a shame that Western politicians are just waking up to the fundamental truth that he who controls the resources, controls the world.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.