Renewables and electrification? Nothing happens without copper

2021.02.12

On Wednesday, Feb. 10, copper prices tore past $3.79 a pound ($8,350 a tonne), the highest since March 2012, on expectations that a nearly $2 trillion stimulus package will be passed by the US Congress and lead to higher inflation.

Though US inflation is currently below the US Federal Reserve’s 2% target, there are mounting concerns that a big increase in the money supply, combined with central banks’ determination to keep interest rates low, and an expected surge in post-pandemic consumer spending, after vaccination programs run their course, will push inflation past the dreaded 2% mark.

And while the prevailing narrative over the past year in the US has been the covid-related economic slowdown, the problem may soon switch to stopping the economy from overheating. Remember, the Biden administration’s $1.9T American Rescue Plan is on top of December’s $900 billion aid package, and last April’s $2T coronavirus relief bill. The additional spending could easily ignite inflationary pressures, especially with economists predicting US economic growth this year greater than 5%. More money sloshing around the financial system than can be hoovered up by demand, spells higher prices.

In a recent op-ed in the Washington Post, via the Globe and Mail, former Bill Clinton-era treasury secretary Lawrence Summers, who was the architect of Barack Obama’s 2009 stimulus package, had this to say about inflation:

“Can and will the Fed control the situation if inflation starts to rise? History is not encouraging,” Summers wrote. “And given the Fed’s guidance about keeping [interest] rates low, the economy’s high degree of leverage, and pressures on the dollar, I worry that containing an inflationary outbreak without triggering a recession may be even more difficult than in the past.”

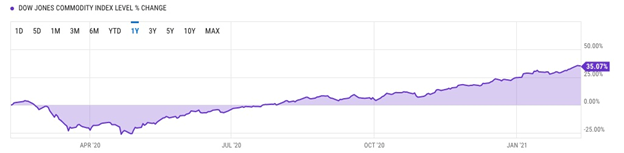

A sinking dollar usually bodes well for commodities, including copper. Over the past year, the greenback has dipped 9.5%, while the Dow Jones Commodities Index has gained 35%. Commodities are back, big time.

“The idea that US stimulus is going to lead to higher inflation has taken hold this week, which is a positive for copper and other commodities used as a hedge against inflation,” Tom Mulqueen, an analyst at Amalgamated Metal Trading told Reuters.

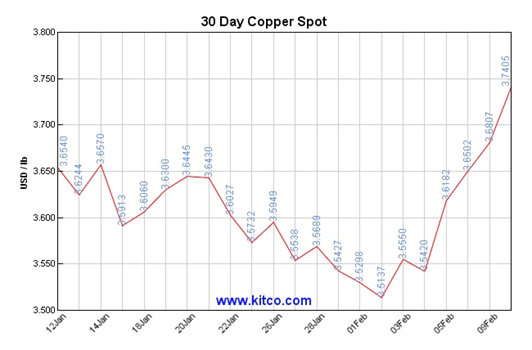

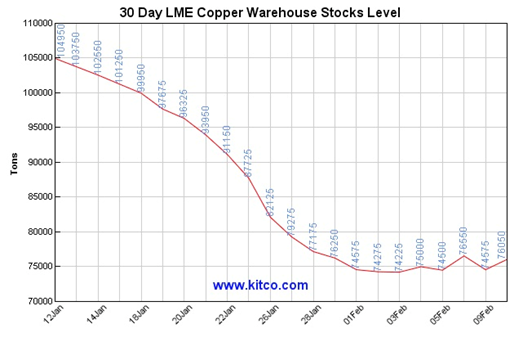

Frenzied copper buying is reflected in falling copper warehouse stock levels. Thirty-day LME stocks have so far stayed mostly below 75,000 tons in February, corresponding to a jump in the 30-day copper spot price, from $3.51/lb on Feb. 1 to $3.75, Wednesday.

The trend of high copper prices and low warehouse stocks holds in the long-term. Taking a 5-year chart, copper skidded to nearly $2 a pound in March 2020, at the depths of the covid-19 pandemic — close to where prices were in 2016 — but since mid last year have taken off. Copper stocks in LME warehouses rose from February to August, corresponding with slowed global growth and lower demand for metals due to covid-19, then sharply began dropping towards the end of last year, as the copper price ticked upward, mostly due to Chinese buying.

Rising more than 22% in 2020, copper had its best year since 2017, with prices boosted by hopes for “green” stimulus (the red metal is an important component of electric vehicles and renewable energy systems. The United States, EU and China have all promised trillions worth of green infrastructure spending), the global 5G build-out, China’s recovery from the coronavirus, and virus-related supply disruptions in top copper producers Chile, Peru and Mexico.

“This current price strength is not an irrational aberration, rather we view it as the first leg of a structural bull market in copper,” Goldman Sachs analysts said in December, with the investment bank raising its 12-month forecast from $7,500 to $9,500 a tonne, or $4.30/lb.

Record Chinese imports

China is a critical part of the copper growth story.

The Chinese economy became the first major world economy to return to its pre-virus growth trajectory, when it posted positive numbers in the second quarter of 2020. And despite full-year growth in China being just 2.3%, the lowest in decades, it was the only major economy to avoid a contraction last year, as many nations struggled to contain the virus.

Chinese growth statistics have always figured prominently in copper price forecasts – no surprise considering that China is responsible for just under half of the world’s production of copper and copper alloys semis, the industry term for first-stage products made from refined copper.

The Asian superpower is also the largest importer of unwrought copper, along with copper ores and concentrates.

Its manufacturing sector back on track, China’s copper imports rose sharply in 2020. According to customs data, in 2020 the country imported 6.68 million tonnes of unwrought copper and copper products, up one third from 2019.

The scrap factor

China also capped 2020 with a 10th consecutive month of expansion in its manufacturing sector, setting the stage for a sterling first quarter. But while continued Chinese demand for copper, used widely in construction, communications, transportation and energy transmission, will certainly be whetted by strength in its economy, Reuters metals columnist Andy Homes points to another reason China is buying so much copper — scrap.

Recall that in 2017, China announced to the rest of the world a complete ban on imports of solid waste. President Xi Jinping’s “war on foreign garbage” targeted not just plastic, which grabbed headlines, but also scrap copper and aluminum.

The effect of the scrap metal ban on China’s copper industry was profound. From importing 3.6 million tonnes of copper scrap in 2017, both to refine into new metal and to feed the manufacture of downstream products, copper scrap imports fell to 2.4Mt in 2018, 1.5Mt in 2019, and 944,000t last year.

Nearly all of this “lost” scrap had to be replaced by refined metal. According to Home, China was a net importer of 4.5 million tonnes of refined copper in 2020, an increase of 1.2 million tonnes over 2019.

Strong manufacturing demand and even stronger stockpiling demand were in the mix but a significant part of that extra call on metal was simply to compensate for the loss of imported copper scrap.

The world needs more copper

Copper’s widespread use in construction wiring & piping, and electrical transmission lines, make it a key metal for civil infrastructure renewal.

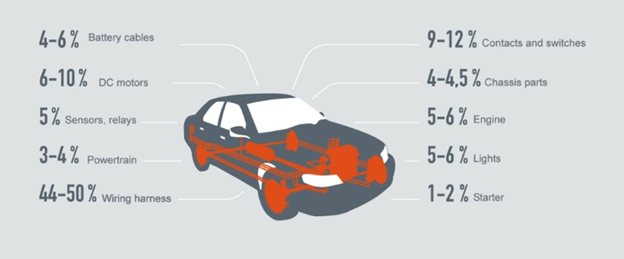

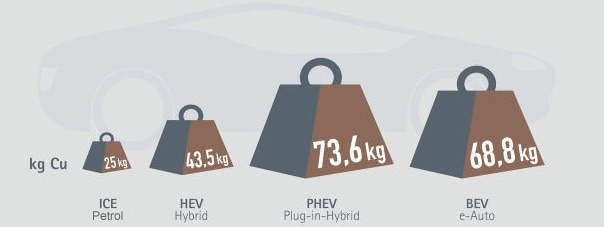

The continued move towards electric vehicles is a huge copper driver. In EVs, copper is a major component used in the electric motor, batteries, inverters, wiring and in charging stations. An average electric vehicle contains about 4X as much copper as regular vehicles. Electrification includes not only cars, but trucks, trains, delivery vans, construction equipment and two-wheeled vehicles like e-bikes and scooters.

According to the Copper Development Association (CDA) a high-speed train required 10 tonnes of copper components, plus another 10t in the power and communication cables per kilometer of track. Even the most basic gasoline-powered passenger car requires a kilometer of copper wiring, and between 15 and 28 kilos of copper, depending on its size. A traditional internal combustion engine cannot be built without 23 kg of Cu.

It’s not only the copper required for EVs, but charging stations. One of the largest manufacturers of public charging stations, ChargePoint, is targeting a 50-fold increase in its global network of loading spots by the mid-2020s. The group in which German companies BMW, Daimler and Siemens hold stakes, aims to operate 2.5 million charging points by 2025, from 53,000 in 2018. A Level 2 charging station requires 7 kg of copper, a direct current fast charger (DCFC) or Level 3 station uses 25 kg.

BloombergNEF forecasts by 2040 there will be a need for 12 million charging points, each requiring about 10 kg of copper. The number of charging stations recently passed the one million mark.

The latest use for copper is in renewable energy, particularly in photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines.

The Biden administration has promised a $2 trillion clean energy plan, to decarbonize American electricity in 15 years and create a net-zero-emissions economy by 2050. Renewable energy projects left on the shelf by the Trump administration, such as offshore wind developments in the northeastern US, could eventually see the light of day.

An important part of the shift away from fossil fuels and the aging electricity grids they feed into, is the “smart grid”. Smart grids use technology that make energy integration easier, and allow for a higher penetration of renewable energy. They are deemed essential for accelerating the use of fully electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids, and for storing energy from wind and solar installations.

The adoption of smart grid technology in developed and developing countries will boost demand for copper strips used in switchgear, devices that protect equipment and circuits from power spikes. Copper is the conductor material used in transformer windings, strips and busbars. Both power and distribution transformers use copper strips.

Another energy trend is the construction of micro-grids. A 2017 study by the CDA found that modern energy infrastructure is moving away from traditional large, resource-consuming electrical grids and toward microgrids that make it easier to distribute power to communities, public institutions, commercial facilities, universities, and even island communities.

Microgrids utilize wind and solar energy systems, which also use copper to run efficiently, as opposed to traditional energy storage systems and fossil-fuel burning plants unless absolutely necessary. Microgrids are also very resilient and decrease the chances of major electrical failure.

President Biden, a tax and spend Democrat firmly in the pocket of the party’s progressive left, wants to drop another $1.8 trillion on infrastructure, including a $50 billion investment in repairs to roads and bridges and $10 billion for transit construction. The plan also targets high-speed rail, bicycling, school construction, expansion of rural broadband, and replacement of pipes and other water infrastructure — all of which will require millions more tonnes of copper, along with other infrastructure metals such as nickel, zinc and aluminum.

Beyond the United States, there is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), consisting of a vast network of railways, pipelines, highways and ports that would extend west through the mountainous former Soviet republics and south to Pakistan, India and southeast Asia.

Research by the International Copper Association found BRI is likely to increase demand for copper in over 60 Eurasian countries to 6.5 million tonnes by 2027, a 22% increase from 2017 levels.

The base metal is also a key component of the global 5G buildout. Even though 5G is wireless, its deployment involves a lot more fiber and copper cable to connect equipment.

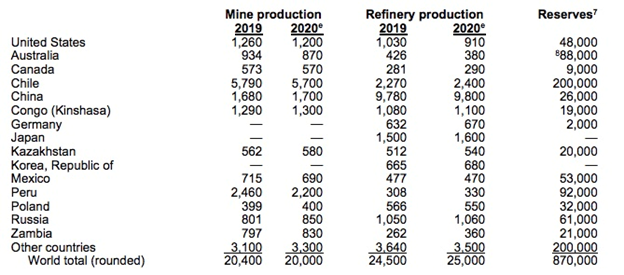

Another report by Roskill forecasts total copper consumption will exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization and electricity demand. Total world mine production in 2020 was only 20Mt. In many countries it takes 20 years to go from discovery through permitting to mining.

Running out of ore

Indeed the big question is, will there be enough copper for future electrification and energy needs, globally? And remember, in addition to electrification, copper will still be required for all the standard uses, including copper wiring used in construction and telecommunications, copper piping, and copper needed for the core components of airplanes, trains, cars, trucks and boats.

The short answer is no, not without a massive acceleration of copper production worldwide.

As we have reported, without new capital investments, Commodities Research Unit (CRU) predicts global copper mined production will drop from the current 20 million tonnes to below 12Mt by 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15Mt. Over 200 copper mines are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

Some of the largest copper mines are seeing their reserves dwindle; they are having to dramatically slow production due to major capital-intensive projects to move operations from open pit to underground.

Exploration companies are having to go further afield and dig deeper to find copper at the grades needed to economically produce copper products for end users. This usually means riskier jurisdictions that are often ruled by shaky governments with an itchy trigger finger on the resource nationalism button. Combine that with production problems and you have the makings of a supply shortage.

In fact, new supply is concentrated in just five mines — Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC.

The current copper pipeline is the lowest it’s been in a century, and not improving. In 2018 Colin Hamilton, the director of commodities research at BMO Capital Markets, said that after the delivery of first copper from Cobre Panama (285-310,000t per year), BMO doesn’t see the next batch of +200,000-tonnes projects until 2022-23 — “when the likes of Kamoa (501,000t per year), Oyu Tolgoi Phase 2, and QB2 (316,000t per year) are likely to offer meaningful supply growth.” These mines are expected to account for 80% of base-case output increases until 2022-23, and its not enough, not nearly enough as we’ve shown above.

A recent report from Jefferies Research LLC concluded: “The copper market is heading into a multiyear period of deficits and high demand from deployment of renewable energy and electric vehicles. Secular demand driver in copper is electric passenger vehicles as the average EV is about four times as copper intensive as the average ICE automobile. Renewable power systems are at least five times more copper intensive than conventional power.”

Beyond batteries

Yet the message of a looming copper shortage that could bring the global electrification shift, and the move from fossil fuels to renewable energy to a screeching halt, or make copper so dear that only the rich can afford to buy finished products made from it, like EVs, isn’t getting through to the mining audience, because copper is not considered critical. It is usually left out of the evolving EV/ battery metals narrative, which in our view, is a huge oversight.

A great example is a story published this week on MINING.com.

The article points out how, despite 2020 being a terrible year for auto sales, it was a very good year for EVs. Last year, EU sales doubled to 1.3 million, with penetration reaching 19% in the fourth quarter, better than sales in China for the whole year. Europe and China are the two biggest markets for electric vehicles.

That, in turn, pushed the MINING.com EV Metal Index to a new record in December, of half a billion dollars, referring to the value of battery metals in newly registered EVs including hybrids. Quoting from the article,

After lagging 2019 for most of the year due to covid-19 disruptions, 2020 ended 23% ahead with $2.64 billion worth of battery metals finding its way into new cars.

Total battery capacity of EVs sold during the month increased 98.5% year on year to over 25 GWh, according to Adamas Intelligence, which tracks demand for EV batteries by chemistry, cell supplier and capacity in over 90 countries. December’s tally lifted the annual total to over 130 GWh, a 40% increase over 2019.

The Toronto-based research firm notes that during December, the amount of lithium in newly sold EVs jumped 112%, cobalt used in battery cathodes rose 85%, and nickel, a key component of NCA and NCM electric vehicle batteries, was up 77%, compared to December 2019.

Conclusion

The surprise in all of this? No mention of copper.

The reality is, there is no shift from fossil fuels to green energy, nor electrification, without the red metal, which has no substitutes for its uses in EVs (electric motors and wiring, batteries, inverters, charging stations) wind and solar energy, smart grids/ microgrids, and 5G.

As we discovered while researching a recent article, with a 30% penetration of EVs, a relatively conservative estimate, we need to find another 20 million tonnes of copper per year over 20 years.

That means an extra million tonnes annually, over and above what we mine now, every year for the next two decades! The world’s copper miners need to discover the equivalent of two Kamoas (the Kamoa-Kakula Project in the DRC is ranked as the world’s largest undeveloped, high-grade copper discovery) at 500,000 tonnes each and every year, while keeping current production at 20Mt.

Remember we still need to cover all the copper demanded by electrical, construction, power generation, charging stations, renewable energy, 5G, high-speed rail, etc., plus infrastructure maintenance/ buildout of new infrastructure.

That might be another 5-7Mt. So not only is there a 20Mt increase in copper usage required for a 30% EV penetration, but another (we estimate) 5-7Mt increase to meet demand for all of copper’s other applications. To keep up, the industry will need to find an additional three Kamoas a year, each producing 500,000t, for the next 20 years! Remember – over 200 copper mines are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.It’s going to be hard enough to keep up the current 20Mt per year let alone add so much more production.

Where is thisnew, and replacement supply going to come from? When copper becomes so rare it hits +$10,000 a tonne, what’s going to happen to 30% EV penetration? High-speed rail? 5G? We suggest that without new copper deposits, all these well-intentioned plans are in jeopardy.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.