Quantifornication round 4 on its way

2019.07.06

Californication is a brilliant 1999 song by the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Many of the lyrics reference the often insane, unrealistic, impossible dream images Hollywood sells to the world.

Quantifornication is the term I coined for what the Federal Reserve is selling to the world – the unrealistic, insane fiat dream that the monetary policy employed by the Fed known as quantitative easing (QE), can fix the predicament we are in.

Once seen as a one-off emergency measure – kind of like an epidermal for excruciating back pain – QE has become the monetary norm. Not least because pushing interest rates to zero or even below zero, is great for stock markets. When the cost of borrowing is low, businesses are more comfortable taking on debt, thus growing their profits and earnings per share.

The pullback in North American stock markets last fall was blamed on the Fed’s raising interest rates. Conversely, stocks have rallied since the central bank in June signaled it will likely hold rates steady or even cut them, at its next meeting on July 31. Bond markets are anticipating at least two rate reductions by the end of the year.

This is exactly what President Trump wants, low interest rates and a low dollar, in order to goose exports and fix the US trade deficit he campaigned on in 2016.

But QE is a lopsided solution to a weak economy; its effects benefit corporations and wealthy investors but do little to help the average citizen. It was largely the failure of globalization, including QE in the US and Europe, that led to the disgruntlement with “elites” such as the politicians in Washington and Brussels, and the subsequent rise of nationalism that helped elect Trump and gave rise to Brexit.

You’d think we would have learned our lesson, but we haven’t. From Australia through Asia, Southeast Asia, India, Europe and the United States, quantifornication is back in style. This article tries to figure out where it might be going.

ECB to cut rates

The US central bank initiated a series of rounds of quantitative easing between 2008 and 2015, back then seen as throwing a lifeline to the economy which was drowning in the financial crisis. Other countries, also hard it, soon followed with their own monetary easing, including Japan and the European Union.

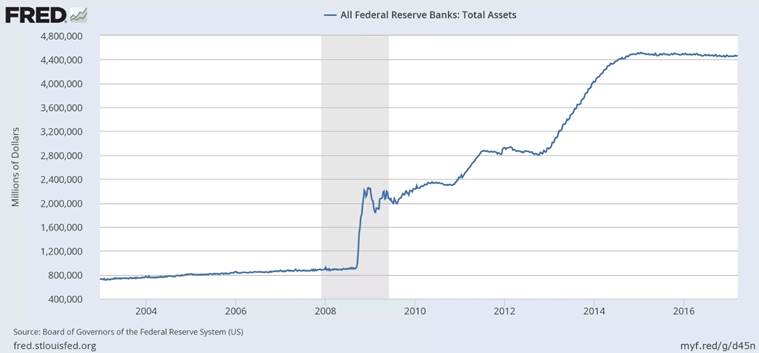

In 2014 the US Federal Reserve felt positive enough about the US economy returning to acceptable employment and inflation figures, that it reversed its QE policy – by gradually raising interest rates and “winding down” (ie. selling off) its balance sheet of US Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities – that had ballooned to $4.8 trillion in October, 2014.

The European Central Bank also embarked on a policy of “monetary tightening” but whereas the Fed began tapering asset purchases in October 2017, the ECB only just pulled the plug on monetary easing this past December, when officials capped the size of their bond-buying program at 2.6 trillion euros ($2.9 trillion).

The bank’s Governing Council led by President Mario Draghi had been hoping to continue tightening, following the Fed’s path of interest rate raises that topped at 2.5% (the Federal Funds Rate), and also wind down asset purchases, but things haven’t exactly worked out as planned. The EU’s economy has been slammed by low growth particularly from China its second biggest trading partner, low manufacturing output, and persistently low inflation – a sign that the world’s largest trading block has stopped growing and is in trouble.

The ECB has less room to maneuver than the US, which held interest rates steady at its last meeting in June, and is strongly hinting of a rate cut at the end of the month.

While the Fed can start slashing rates from 2.5%, the European Central Bank’s deposit rate has been at -0.4% since 2016.

Last Thursday Draghi said the ECB expects borrowing costs to stay at present levels “or lower” (the interest rate cut signal) through the first half of 2020. Officials also indicated they will restart their bond-buying program (QE) if needed. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg think the ECB will cut rates by 10 points in September and start a round of monetary easing in January.

“Draghi came into office with a bang, cutting interest rates at his first meeting, and he’s likely to go out with a bang too. We expect him to begin setting the stage for his final act… But we’ll probably have to wait until September for the real drama,” they said.

The news from Germany is particularly bad. The engine of the EU’s economy is showing the weakest business confidence in over six years, its manufacturing sector in a deep funk. Some of the country’s largest companies including Continental, Daimler and BASF are issuing profit warnings.

Bloomberg reported industrial demand and production are falling as German car-makers and suppliers deal with slowing demand from China. The US-China trade war and the prospect of the EU making a disorderly exit from the EU at the end of October is also taking its toll.

China opening

Speaking of China, officials in the Chinese government are finally addressing complaints that the benefits of free trade have only flowed one way since China was admitted into the World Trade Organization in 2001.

The country is opening up its financial sector to more foreign investment and competition. Among measures announced last Saturday, China will scrap foreign ownership limits of financial firms a year earlier, in 2020 versus 2021, and foreign insurers can hold more than a 25% stake in Chinese asset management companies.

The idea behind the opening is to boost demand and create new growth drivers in an economy that, by China’s standards, is faltering. At 6.2%, growth in the second quarter was the weakest since 1992 when the country starting collecting data. Chinese imports in May fell to the lowest of the year.

Contagion

You may be seeing a theme here. The US, China and the European Union are all taking measures to stimulate their weak economies. Japan is also expected to expand stimulus, if inflation falls below its 2% target. The land of the rising sun’s central bank, like the ECB, has gone to negative interest rates, to try and improve economic growth, which limped along at 2.1% in the first quarter.

The People’s Bank of China has taken steps to boost lending, as a way to jumpstart the economy. The central bank said in May it would lower the reserve-requirement ratio for it small and medium-sized banks, releasing the dollar equivalent of $40 billion to encourage more lending to small businesses, Wall Street Journal reports.

The publication quotes one economist saying “China has the ability to ease more, as much as needed. If that happens, I don’t think that Europe is going to go into recession, or the U.S. or Japan.”

Other central banks turning dovish include Turkey, which hacked its interest rate down to the lowest in 17 years, Australia which cut rates for the first time in three years, on China growth worries, New Zealand, India, Malaysia and the Philippines.

Global trade slowed for the seventh straight month in May, and the International Monetary Fund reduced its global growth outlook – already the lowest since the financial crisis of 2008-09 – by almost a point to 2.5% this year.

The United States is doing better than the rest, but growth is weakening there, too. South China Morning Post reported that a gauge of US manufacturing activity fell in May to its lowest since October 2016. Gains in employment, one of the brightest spots in the US economy, fell sharply, heaping pressure on the Fed to deliver an “insurance” rate cut to sustain America’s economic expansion.

QE was a dud

The question, though is, why return to a policy that heaped piles of debt onto countries to such an extent that, should interest rates rise, their payments will be so high, they’re screwed? And the spoils of asset purchases and rock-bottom interest rates really only go to rich corporations and wealthy investors. Add the tremendous increase in stock buybacks after the Trump administration’s $1.5 trillion tax cut and overseas profits repatriation in late 2017, and you begin to see why all is not well in the land of the brave, home of the free.

I’ve always argued that QE was a dumb idea. Turns out that, with some retrospection, others agree. Here is what I said about quantifornication back in 2012, and again in 2016. Remarkable how so little changed, in particular the inequality that US monetary easing brought about.

2012:

The initial Fed response to the subprime mortgage crisis was to lower interest rates, then, having no traditional tools left in its toolbox the Fed introduced a new policy – quantitative easing (QE).

In September of 2008 the $1.7 trillion QE1 was started. The Fed purchased mostly mortgage backed securities and established a commercial paper lending facility. In October of 2010 QE2 started. At $600 billion, QE2 was much smaller then QE1 and its buying was mostly confined to purchasing long term government bonds.

QE1 & QE2 failed to restart the economy and housing market.

The Federal Reserve has just launched QE3. Key components are:

- The creation of $40 billion a month to buy MBS’s

- The continuation of Operation Twist #2

- An open-ended commitment to keep purchasing securities at whatever level is judged necessary until the labor market improves “substantially”

- An extension of the 0.0% to 0.25% target range for the Fed Funds rate until at least mid 2015

The definition of insanity is “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

“The Committee agreed today to increase policy accommodation by purchasing additional agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $40 billion per month. These actions should put downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and help to make broader financial conditions more accommodative. If the outlook for the labor market does not improve substantially, the committee will continue its purchases of agency mortgage-backed securities, undertake additional asset purchases, and employ its other policy tools as appropriate…” US Federal Reserve

“We will be looking for the sort of broad-based growth in jobs and economic activity that generally signal sustained improvement in labor market conditions and declining unemployment.” Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke

How effective have all these programs, with trillions of dollars spent, been? Not very…

New orders for manufactured durable goods in August decreased $30.1 billion or 13.2 percent to $198.5 billion. This decrease was the largest since January 2009.

Our overall workforce participation rate looks pretty dismal.

Shocking stats:

- Nearly half of Americans die broke

- One out of three Americans has no savings

- Our labor force participation rate is at a 30 year low

- Household income has fallen to 1995 levels

- There are over 46 million Americans currently receiving food assistance – that’s one out of every seven people

- From 2007 to 2010, a typical US family lost 39% of its wealth

- The Gini index, a measure of household income inequality, increased 1.6 percent in 2011, its first annual increase since 1993

The middle class has shrunk to just under half the US population for the first time in decades, with more of the population shifting to the extremes both above and below the middle.

Allianz’s Global Wealth Report 2015 dubs the U.S. the ‘Unequal States of America’ because the U.S.’s wealth inequality is even more gaping its income inequality.

Allianz calculated each country’s wealth Gini coefficient — a measure of inequality in which 0 is perfect equality and 100 would mean perfect inequality, or one person owning all the wealth. It found that the U.S. had the most wealth inequality, with a score of 80.56, showing the most concentration of overall wealth in the hands of the proportionately fewest people.

When the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) examined income inequality, it found that the U.S. has the fourth highest income Gini coefficient — 0.40 — after Turkey, Mexico, and Chile.

The U.S. Federal Reserve ended their quantifornication program in 2014.

The S&P has more than doubled since 2009, while the Dow Jones has actually tripled.

Stock buyback programs, fueled by CEOs borrowing hugely from the bond market, have supported the market since the Federal Reserve stopped pumping money into the system.

A recent editorial in the South China Morning Post looking back at QE, backs my assertions, in presenting four reasons why quantitative easing isn’t the solution to the global economy’s problems, right now:

Most worryingly, quantitative easing has exacerbated social divides. The wealthy have benefited from higher asset prices while those with no financial assets have seen the returns on their savings shrivel. The reality is that quantitative easing has contributed to rising populism in Europe and America.

Forbes is more sanguine in its impression of easing programs. QE makes it easier (and cheaper) for businesses to borrow money, it keeps consumer debt reasonable due to such low borrowing rates, and by increasing the money supply, keeps the currency low, making exports cheaper and US stocks more competitive to foreign investors.

However the column by Tyler Gallagher, a member of Forbes Finance Council, also comments on the inequalities QE engenders. Number one is the fact that it benefits wealthy borrowers and corporations but not the average Joe and Jane:

QE can, therefore, possibly lead to social unrest if the rich and large corporations can borrow at the lower rates, leaving average citizens in their wake. QE also increases the deficit, which impacts all taxpayers, but has less effect on the wealthy.

Currency war?

One of the risks of concurrent rounds of quantitative easing among the world’s largest economies, is a currency war. As we’ve previously written, the US government now, under President Trump, is preparing for what could be a full-blown currency war, between the United States, the European Union and China – plus whoever else the US president happens to be targeting.

For more on this read US prepares for currency war

Recently the Treasury Department came out with a report that recommended nine trading partners should face scrutiny over their currencies – China, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Ireland, Italy, Malaysia, Vietnam and Singapore – showing that the US is paying close attention to who is devaluing and by how much.

Andrew Moran, writing for Liberty Nation, argues nothing good can come of a race-to-the-bottom round of currency devaluations. Even though cheaper imports would help middle class Americans’ purchasing power, it’s not worth it considering the damage it would due to the international monetary system, Moran writes:

Like a military conflict and a trade war, there aren’t any victors. It can be difficult to determine when central banks fire the first shots, but these bullets are usually pointed at their own heads because a currency war is more like currency suicide. The act of destroying any semblance of value will inevitably harm a nation and its economy in myriad ways, from slashing rates to creating price inflation.

Once competitive devaluation begins though, the US as the largest economy has no choice but to participate. But it would be tough to win. Being the world’s reserve currency means there is constant demand for dollars. The US can’t devalue its currency so low as to squelch demand for Treasuries, which it needs to sell to foreign investors in order to finance its $22 trillion debt. Many people also don’t realize that as the reserve currency, the United States must run a trade deficit – it’s only a question of how large that deficit will be.

There are two other possibilities, according to Joachim Fels of Pimco, a global investment firm, interviewed on CNBC recently. One possibility is if everyone eases at once, and currencies don’t move very much, a currency war would be averted. As for who could win a currency war, Fels picks the United States, because the Federal Reserve has more room to cut interest rates than the ECB or the Bank of Japan, so the US would win in the sense that the dollar is more likely to weaken than strengthen, he said.

Limited options

Taking that idea further, Wall Street Journal presents a couple of scenarios, should global growth stall and key economies enter recessions. If the downturn is fairly minor and cyclical, then most central banks would have the easing tools needed to deal with it.

However, if the world economy is hit with a big shock like in 2008, central bankers might find their options are limited, especially because interest rates in the US are a lot lower than previous recessions. In Europe and Japan they’re negative. The Wall Street Journal states:

But were a recession to loom that raises unemployment and brings inflation toward zero, even the Fed could run out of conventional ammunition quickly. It shaved rates by more than 5 percentage points in a little over a year from 2007 to late 2008. It cut rates by a similar amount from 2001 to 2003 after the tech bubble burst, even though that recession was milder than the one during the financial crisis. It now has less than half that much room in which to start lowering rates before it hits negative-rate territory.

Central banks in Europe are in the trickiest spot, with policy rates below zero in the vast majority of the region, including the eurozone, Sweden, Switzerland and Denmark. Cutting rates more in those regions wouldn’t do much to stimulate their economies and could further weaken the commercial banks that must pay those negative rates to their central banks.

Tempting a crash

The elephant in the room nobody wants to talk about is the debt crisis. Seeking Alpha contributor Ronald Surz wrote a piece where he points out that global debt has reached a record high. The official numbers are $184 trillion but Surz thinks that’s underestimated by a factor of 2.5X. The more likely figure he writes is $460 trillion, which is 560% of global GDP, and $215,000 per capita. The three most indebted countries are the US, China and Japan, which together represent about half of global debt.

But why worry about it? The Fed certainly isn’t. It still has about $4.5 trillion in government debt and mortgage-backed securities on its balance sheet after earlier rounds of monetary easing. Surz writes:

Debt brought the world to its knees in 2008. Paradoxically, disaster was circumvented by doubling down with even more debt, deferring the consequences to sometime in the future. That future is rapidly approaching. In The Coming Global Financial Crisis: Debt Exhaustion, Charles Hugh Smith observes:

The global economy is way past the point of maximum debt saturation, and so the next stop is debt exhaustion: a sharp increase in defaults, a rapid decline in demand for more debt, a collapse in asset bubbles that depend on debt and a resulting drop in economic activity, a.k.a. a deep and profound recession that cannot be “fixed” by lowering interest rates or juicing the creation of more debt.

Conclusion

We are currently experiencing deja vu where it comes to the global economy. In 2008-09 the financial crisis hastened some creative thinking among central bankers. The quantitative easing solution that followed proved popular, so popular that any suggestion of raising interest rates beyond rock-bottom levels sends stock markets into a spin.

When times get tough, the first line of attack is monetary easing. The guests at this party are used to the punch bowl and they see no reason to take it away. It’s highly addictive. But this punch comes with an after-taste, in the form of inequality. How far are central banks willing to go to please their corporate paymasters while continuing to impoverish their middle classes?

QE4 carries with it the risk of a currency war that could lead to hyper-inflation and even stagflation if interest rate cuts and asset purchases fail to stimulate growth. Quantitative easing also kicks the debt can down the road, heightening the risk of another Great Recession. Do we really want to go there?

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.